Abstract

This paper applies the mechanics-based approach and five machine learning algorithms to classify the failure mode (leak or rupture) of steel oil and gas pipelines containing longitudinally oriented surface cracks. The mechanics-based approach compares the nominal hoop stress remote from the surface crack at failure and the remote nominal hoop stress to cause unstable longitudinal propagation of the through-wall crack to predict the failure mode. The employed machine learning algorithms consist of three single learning algorithms, namely naïve Bayes, support vector machine and decision tree; and two ensemble learning algorithms, namely random forest and gradient boosting. The classification accuracy of the mechanics-based approach and machine learning algorithms is evaluated based on 250 full-scale burst tests of pipe specimens collected from the open literature. The analysis results reveal that the mechanics-based approach leads to highly biased classifications: many leaks erroneously classified as ruptures. The machine learning algorithms lead to markedly improved accuracy. The random forest and gradient boosting models result in the classification accuracy of over 95% for ruptures and leaks, with the accuracy of the decision tree and support vector machine models somewhat lower. This study demonstrates the value of employing machine learning models to improve the integrity management practice of oil and gas pipelines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Introduction

Buried steel pipelines are part of critical infrastructure systems in a modern society and widely recognized as the most efficient and safest means to transport crude oil, natural gas and other hydrocarbon products. The structural integrity of these pipelines is threatened by various failure mechanisms such as the third-party interference, corrosion, stress corrosion cracking and ground movement. Among them, cracking is one of the most serious failure mechanisms [16]. According to the data released by the Canadian Energy Pipeline Association [14, 15], cracking accounted for 15.8% and 13% of the total incidents on oil and gas transmission pipelines in Canada between 2010 and 2014 and 2016–2020, respectively. When an operating pipeline fails at a longitudinally oriented surface (i.e. part through-wall) crack due to internal pressure, the remaining ligament at the crack is severed, and the surface crack becomes a through-wall crack [2, 40]. Two failure modes of the crack are commonly recognized, namely leak and rupture [40, 61]. A failure is classified as a leak, also commonly referred to as a large leak in practice [52], if the longitudinal extension of the through-wall crack resulting from the failure of the surface crack is arrested or stabilized; it is defined as a rupture if unstable extension of the through-wall crack in the longitudinal direction takes place [69]. Ruptures of pipelines have much more severe consequences in terms of human safety and environmental impact than leaks [42, 52]. Based on incidents data corresponding to the onshore natural gas transmission pipelines in the United States between 2002 and 2013, Lam and Zhou [43] reported that the likelihoods of ignition were around 3% and 30% in leak and rupture incidents, respectively. They also found that 75% of fatalities and 83% of injuries were due to ruptures. Bubbico [11] performed a similar analysis using data collected by PHMSA between 2010 and 2015 and concluded that for underground natural gas pipelines, the likelihoods of ignition were 7.6% and 30.8% for leak and rupture incidents, respectively. Therefore, the accurate prediction of the potential failure mode at a surface crack has significant implications for quantifying the failure consequences.

Several full-scale burst tests were conducted by different researchers [2, 40, 59, 63] to investigate the failure modes of pipes containing surface cracks. Shannon [61] proposed that the leak and rupture failure modes be separated by comparing the nominal hoop stress remote from the surface crack at failure, σhb, and the remote nominal hoop stress to cause unstable longitudinal propagation of the through-wall crack, σhr. A rupture will occur if σhb ≥ σhr; otherwise, a leak will occur. Note that the lengths of the surface crack and its resulting through-wall crack are assumed to be the same in this approach. However, equations for σhb and σhr proposed by Shannon [61] only take into account the flow stress but not fracture toughness of the pipe steel, and therefore may not be adequate for pipelines containing surface cracks.

Many models have been developed to evaluate the failure stress of pipelines containing surface and through-wall cracks, for example, the well-known Battelle (i.e. Ln-Sec) model [40] and modified Battelle model [38, 39], CorLAS model [34, 55], PAFFC [45], PRCI MAT-8 [4, 5], and failure assessment diagram-based approaches recommended in API 579 [3], BS 7910 [10] and R6 [24]. However, the employment of these models in Shannon’s approach to separate failure modes has, to our best knowledge, not been reported in the literature. The most relevant work is perhaps reported by Kiefner et al. [40], which is the basis of Shannon’s approach. Kiefner et al. conducted 140 experiments using full-scale pipe specimens, of which 92 and 48 specimens contain through-wall and surface cracks, respectively. For the 48 specimens with surface cracks, in addition to the actual failure stresses (i.e. σhb), their failure modes were also reported. The actual failure stresses were then compared with the predicted σhr for the 48 specimens, such that the predicted failure modes are compared with the actual failure modes of these specimens. Although a good agreement between the predicted and actual failure modes is reported in [40], this approach is inadequate for in-service pipelines because σhb and σhr cannot be measured and must be evaluated to predict the failure mode.

As an alternative to Shannon’s mechanics-based approach, machine learning (ML) models are suitable tools to deal with the leak-rupture separation, which is a typical binary classification problem. ML algorithms have been widely applied to the classification tasks in the pipeline integrity management practice [56]. Zhou et al. [69] employed the logistic regression to predict the probability of rupture for corroded pipelines as a function of the depth and length of the corrosion defect. Carvalho et al. [13] applied the multi-layer perceptron neural network to signals from inspection tools based on the magnetic flux leakage technology to predict the presence of defects on pipelines and categorize the types of defect; Cruz et al. [21] employed the neural network model to signals from the ultrasonic inspection tools to perform the same prediction and classification, and Liu et al. [47] used the particle swarm optimization support vector machine (SVM) on eddy-current signals to classify the defects on pipelines. Zadkarami et al. [67, 68] applied the neural network model to the pipeline inlet pressure and outlet flow signals to categorize the leakage size and position into ten classes.

The objective of the present study is to apply both the mechanics-based approach and ML models to classify the failure modes of pipelines containing longitudinal surface cracks by considering the pipe geometric and material properties and dimensions of the crack. The main novelty of the study is two-fold. First, while many models to predict burst capacities of pipelines containing surface-breaking and through-wall cracks, respectively, have been developed as described in the previous paragraphs, the incorporation of these models in a mechanics-based framework to predict the failure mode of pipelines containing surface cracks has not been reported in the literature. The present study sheds light on the adequacy of the mechanics-based approach in terms of the failure mode determination. Second, we develop machine learning models to predict the failure mode of pipelines containing surface cracks and compare the accuracy of the mechanics-based approach and machine learning models. To the best of our knowledge, similar investigations are unavailable in the literature. A database of full-scale burst tests involving pipe specimens containing surface cracks is collected from the open literature as the basis for training the ML models and also comparing the predictive accuracy of the mechanics-based approach and ML models. For the mechanics-based approach, the well-known CorLAS model ([55, 64, 66]) is selected to evaluate σhb, whereas the Battelle model and an extension of the CorLAS model for through-wall cracks [55] are used to evaluate σhr. Five ML models are considered for comparison with the mechanics-based approach, namely the naïve Bayes (NB) model, SVM, decision tree (DT), random forest (RF) and gradient boosting (GB).

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section "Mechanics-based models for failure mode classification" describes the two main components of the mechanics-based approach for classifying the failure mode, i.e. the models for calculating σhb and σhr, and illustrates the application of the mechanics-based approach on a hypothetical example; Section "Machine learning classification algorithms" describes the five ML models that are employed to classify the failure mode; Section "Full-scale burst tests of pipes containing longitudinal surface cracks" presents the details of the full-scale burst test data collected from the open literature and employed in the present study; Section "Classification results using mechanics-based models" introduces the metrics for evaluating the predictive performance of a classifier and presents the predictive performance of the mechanics-based approach applied to the full-scale test dataset described in Section "Full-scale burst tests of pipes containing longitudinal surface cracks"; the training and optimization of the five ML models and their predictive performances based on the full-scale test dataset are discussed in Section "Machine learning models for failure mode classification", followed by conclusions in Section "Conclusion".

Mechanics-based models for failure mode classification

Burst capacity model for surface cracks

Various burst capacity models have been proposed and employed in the industry for pipelines containing longitudinally oriented surface cracks over the past several decades, as described in the previous section. These models can generally be grouped into two categories, namely the pipeline-specific and generic crack assessment methods that are based on the failure assessment diagram concept [19]. Performances of some of the burst capacity models mentioned in Introduction have been evaluated and compared in the literature, e.g. Rothwell and Coote [60], Yan et al. [65], Yan et al. [64] and Guo et al. [28]. It has been consistently shown that the CorLAS model, the model built in the CorLASTM software [22] that is well known in the pipeline industry [3, 54], is one of the most accurate burst capacity models for pipelines with longitudinal surface cracks. Therefore, the CorLAS model is employed in the present study to evaluate σhb. For clarity, this model is referred to as the CorLAS-S model (i.e. CorLAS model for surface cracks) to be distinguished from the CorLAS-based model for through-wall cracks as described in Section "Burst capacity models for through-wall cracks".

The CorLAS-S model was originally proposed by Jaske and Beavers [33] to predict burst capacities of pipelines containing longitudinal crack-like surface breaking flaws based on elastic-plastic fracture mechanics principles. The model has been continuously updated since then and is now in Version 3 [34, 55] with main formulations given by,

where A is the area of the longitudinal profile of the surface crack with a length 2c and a maximum depth a, as illustrated in Fig. 1; A0 is the reference area that equals 2cwt with wt denoting the pipe wall thickness; M is the Folias factor that accounts for the defect bulging induced stresses due to pipe internal pressure [26], and D is the pipe outside diameter. It is emphasized that the CorLAS-S model assumes the crack profile to be semi-elliptical if a detailed crack profile is unavailable. Therefore, cracks with other profiles (e.g. rectangular) need to be converted into equivalent semi-elliptical profiles. Such a conversion is typically carried out by maintaining the same area and depth of the crack profile while obtaining an equivalent crack length [28, 35, 40]. For example, a rectangular crack with a length 2crec will have an equivalent semi-elliptical crack length 2c = (2crec)(4/π) based on the above criterion.

As shown in Eq. (2), cracks are evaluated using the flow strength- (i.e. σff) and fracture toughness-based (i.e. σft) criteria in the CorLAS-S model. The criterion that leads to the lower failure stress is used to evaluate σhb. As such, σff is defined as (σy + σu)/2, where σy and σu denote the yield strength and tensile strength of the pipe steel, respectively. The quantity σft is directly related to the local failure stress, σl (Eq. (3)). If the crack is on the pipe external surface, σft = σl, whereas an adjustment is needed for cracks on the pipe internal surface to account for the effect of internal pressure on the crack surface. The value of σl is obtained by solving for the stress satisfying Jt = Jc, where Jt and Jc are the total applied J-integral at the crack tip and fracture toughness of the pipe steel, respectively. If direct measurements of the fracture toughness of the pipe steel are unavailable, the following empirical equation can be used to estimate Jc from the Charpy V-notch (CVN) impact test result [35]:

where Cv and Ac denote the CVN impact energy and net cross-sectional area of the Charpy impact specimen, respectively. Detailed equations for calculating Jt are given in Appendix A.

Burst capacity models for through-wall cracks

Kiefner et al. [40] proposed the following semi-empirical model, also known as the Ln-Sec or Battelle model, to compute σhr based on the plastic-zone correction solution for cracks in flat plates with an infinite width [23]:

where Kc denotes the fracture toughness of the pipe steel in terms of the stress intensity factor; σf represents the flow stress of the pipe steel, and all other variables have been defined previously. Note that σf = σy + 68.95 MPa, which is different from σff in the CorLAS-S model. Since Kc may not be available in practice, it can be evaluated by the following empirical equation that is equivalent to Eq. (5) [50]:

where E denotes the modulus of elasticity of the pipe steel. Kawaguchi et al. [36] pointed out that Eq. (7) tends to be non-conservative for pipe steels with Cv greater than 130 J and grades higher than X65 and introduced a static Charpy test to improve the accuracy [37]. However, it is unclear if the static Charpy test has been adopted in practice.

Polasik et al. [55] modified the CorLAS model to apply it to through-wall cracks. This is referred to as the CorLAS-T model in the present study. According to this model, σhr can be evaluated by solving for the stress satisfying JtT = Jc, where JtT is the total applied J-integral at the tip of the through-wall crack (see Appendix A). Both the Battelle and CorLAS-T models are employed in the present study to calculate σhr.

Illustration of mechanics-based approach for failure mode classification

The application of the mechanics-based approach to predict the failure mode is illustrated using a hypothetical example. Consider a pipeline with D = 610 mm, wt = 7.2 mm, σy = 414 MPa and σu = 517 MPa (i.e. X60 steel grade) that contains a single semi-elliptical crack. Figure 2 depicts the failure mode predicted by the mechanics-based approach for various crack lengths and depths, and three representative full-size CVN values (Cv = 25, 50 and 100 J). The solid lines in Fig. 2 correspond to σhb predicted by the CorLAS-S model for surface cracks with different depths and lengths, and the two dashed lines correspond to σhr predicted by the Battelle and CorLAS-T models, respectively, for through-wall cracks with different lengths. The figure indicates that the CorLAS-T model predicts consistently lower σhr values than the Battelle model. Suppose that the Battelle model is used to predict σhr. For surface cracks with a given depth, a rupture is predicted if the solid line corresponding to the crack depth is above the dashed line associated with the Battelle model; otherwise, a leak is predicted. The interception point between the solid and dashed lines defines the critical crack length; that is, rupture (leak) occurs if the crack length is greater than or equal to (less than) the critical length. Since the critical crack length decreases as the crack depth decreases, it follows that rupture (leak) is the more likely failure mode for shallow (deep) cracks. If the CorLAS-T model is used to predict σhr, Fig. 2 indicates that almost all of the considered surface cracks will be predicted to fail by rupture as the solid lines are all above the dashed line corresponding to CorLAS-T except for cases with very short cracks and Cv = 100 J. For this particular example, increasing Cv from 25 to 100 J has no impact on σhb corresponding to a/wt = 0.2, 0.3 and 0.4 as the flow stress-based criterion governs the prediction of the CorLAS-S model. The increase in Cv leads to increased values of σhb corresponding to a/wt = 0.5, 0.6 and 0.7 as the toughness-based criterion governs the prediction of the CorLAS-S model for these cases.

Machine learning classification algorithms

General

There are a great number of machine learning (ML) tools for classification tasks such as neural network and support vector machine (SVM). The ensemble methods, which utilize multiple learning algorithms in one ML model to achieve better predictive performance than using a single learning algorithm, have attracted much attention in the application of machine learning models [56]. Representative ensemble learning algorithms include the adaptive boosting, gradient boosting (GB), random forest (RF) and extremely randomized trees [25, 49, 56]. In the present study, three commonly used single ML algorithms for classification, namely naïve Bayes (NB), SVM and decision tree (DT), and two ensemble classification algorithms, namely RF and GB, are employed to predict the failure modes of the full-scale test data. The three single algorithms are selected because their underlying mechanisms for classification are completely different. RF and GB are selected as they are classic DT-based ensemble ML algorithms and respectively involve bagging and boosting so that the performances of the ensemble methods and conventional DT can be compared. The five selected ML algorithms are described briefly in the following sections.

Naïve Bayes

NB is a simple ML algorithm that utilizes Bayes’ theorem for classification. The term “naïve” indicates the assumption that the input features associated with the data are mutually independent conditional on the class variable. For a given sample with a class variable y and m input features (x1, x2, …, xm), NB is applied as follows:

where P(y) is the prior probability of class y; P(xi| y) is the likelihood of input feature xi (i = 1, 2, …, m) given class y; “∝” denotes proportionality, and \(\hat{y}\) is the prediction given by NB. P(y) is usually set to be the frequency of the corresponding class variable in the training dataset. For continuous input features, P(xi| y) is typically evaluated based on the Gaussian assumption [51].

Support vector machine

SVM was originally developed for the binary classification [18] and subsequently extrapolated to the multiclass classification and regression. Consider that a training dataset consists of n samples, each with m input features and one of the two class variables, such that any sample can be represented as {xj, yj} (j = 1, 2, …, n), where xj ∈ ℝm is an m-dimensional vector representing the input features of the sample, and yj ∈ {−1, +1} is the class label of the sample. The basic idea of the binary classification SVM is to nonlinearly map input vectors into a higher dimensional feature space, where a linear decision hyperplane can be constructed to separate the two classes, simultaneously maximizing the distance between them [18]. However, a rigorous linear separation of read-world data is usually infeasible, resulting in unavoidable misclassifications. Therefore, a strictly positive regularization parameter (C) that determines a trade-off between the number of misclassifications in the training dataset and the distance between two classes is an important hyper-parameter of SVM. Another significant hyper-parameter is the kernel function K, which defines the nonlinear mapping of the input vector into the high dimensional feature space. The commonly used Gaussian (i.e. radial basis function or RBF) kernel is given by Eq. (10),

where γG is the parameter of the Gaussian kernel. SVM has two advantages compared with other classification algorithms: it is not data-greedy and can well resist the effects of outliers [12].

Decision tree

DT can be used to deal with both classification and regression tasks. Therefore, DT is also referred to as the classification and regression tree (CART) [9]. A DT is built by splitting nodes of the tree structure into two child nodes recursively. The nodes that are split in a DT are decision nodes while those cannot be further split are called leaf nodes or leaves. The decision node located at the top of the (inverted) tree is the root node. From the root node, a DT grows as follows. First, given the training dataset with different input features, select the best split of each feature that optimizes the splitting criterion. Second, select the best split of the decision node among the best splits of features that optimizes the splitting criterion. Finally, split the decision node using the best split and repeat the process until a pre-determined stopping criterion is satisfied. A commonly used splitting criterion for classification trees is the Gini impurity index (GI), which is a measure of the total variance across all classes [32] and minimized to find the best split of a decision node. A natural stopping criterion for classification trees is that all leaves are pure, namely, each leaf node consisting of samples of the same class. Other stopping criteria such as limits on the levels of the tree or on the number of decision nodes could also be used. Compared with other ML algorithms, DT is simple, understandable and interpretable [32]. Furthermore, DT is a white box model [48] since its prediction is highly explainable as the movement of the sample through the tree can be directly visualized. However, DT is susceptible to overfitting [7], which may lead to a lack of robustness in the prediction and a more tedious hyper-parameter tuning process.

Random forest

RF [8] is a DT-based ensemble ML algorithm that involves bootstrap aggregating (known as bagging). An RF consists of a large number of DTs, and the split of every decision node in each DT is based on a randomly selected subset of the input features, unlike conventional DT, which considers all input features. To train an RF, numerous subsets of data are first randomly sampled with replacement (i.e. bootstrap sampling) from the training dataset. Each bootstrapped subset of data is then used to generate a DT. When this RF is applied to a new sample, each DT in the forest provides a prediction of the class of the sample. The class predicted by the majority of the trees in the RF is the final prediction, i.e. aggregating. Compared with DT, RF is capable of handling numerous input features, more robust to deal with outliers, and less susceptible to overfitting. However, the interpretability of the algorithm is simultaneously sacrificed due to numerous DTs in the forest. RF also inherently evaluates the importance of each input feature, which will be described in Section "Machine learning models for failure mode classification".

Gradient boosting

GB was first proposed for regression and subsequently extrapolated for classification [27]. It establishes a forward stepwise additive structure that amalgamates the predictions given by several sequential weak learners, which are typically DTs [29]. Unlike RF, the weak learners in GB are regression trees even if GB is used for classification. Given the training dataset, the goal is to develop a model that maps the input features to the corresponding class variable for each sample in the dataset by minimizing a loss function, which is typically the log-likelihood (also known as deviance) in GB for classification. The procedure is iterative in that the model is continuously and sequentially revised by adding regression trees to fit the residual of the model prediction at the previous step of iteration so that the value of the loss function continuously decreases. A critical hyper-parameter of GB is the learning rate. It scales the step length in search for the minimum value of the loss function and also limits the contribution of each regression tree. The numerical prediction given by the additive regression trees is transferred to a probability measure through the logistic function, which quantifies the probability of the sample belonging to the positive class to achieve classification. More details of GB can be found in [29].

Full-scale burst tests of pipes containing longitudinal surface cracks

A total of 250 full-scale tests of pipe specimens containing single longitudinal surface cracks are collected from the literature [2, 20, 31, 36, 40, 57,58,59, 63]. The test data include 135 leaks and 115 ruptures. All 250 data points have D/wt values greater than or equal to 20 except the eight test specimens reported in [63], the D/wt of which equal 19.50 and 19.95. Therefore, all specimens are considered thin-walled. The yield and tensile strengths as well as Cv of each pipe specimen are provided in the corresponding source documents. The crack profiles in the dataset are either rectangular or semi-elliptical. Five specimens in [63] have cracks on the internal pipe surface; nineteen specimens, also reported in [63], have no information as to whether the cracks are internal or external. All the other specimens have external cracks. In the subsequent analyses, cracks with unknown positions (internal or external) are assumed to be external cracks as such information is required for the evaluation of σhb (see Eqs. (1) to (3)). However, it is noted that the crack position has a marginal impact on σhb. A brief summary of the geometric and material properties of the pipe specimens in the test database collected is given in Table 1. Details of the test data are provided in Appendix B.

Classification results using mechanics-based models

Evaluation metrics of classifier performance

For binary classification problems, one can define any of the two classes to be positive and the other negative. Depending on whether a classifier correctly or incorrectly identifies the positive and negative classes, there are four possible outcomes of the prediction by the classifier, namely true positive (TP), true negative (TN), false positive (FP) and false negative (FN). FP and FN are also known as type-I and type-II errors, respectively [1]. Given these four possible outcomes, some commonly used evaluation metrics of the performance of a classifier are described as follows. Let nTP, nTN, nFP, nFN respectively denote the numbers of TP, TN, FP and FN after a classifier has been applied to a dataset. The true positive rate (TPR), i.e. sensitivity, and true negative rate (TNR), i.e. specificity, are defined as follows [1]:

Another commonly used metric is the accuracy (ACU), which represents the total percentage of correctly predicted classes:

where ntot = nTP + nFN + nTN + nFP is the total number of samples in the dataset. More sophisticated evaluation metrics such as the F-score and Matthews correlation coefficient have been proposed [17] but are not employed in the present study as the above-described simple evaluation metrics are considered sufficient to quantify the performances of the binary classifiers.

Predictions of the mechanics-based approach based on test data

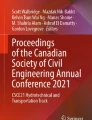

The three models described in Section "Mechanics-based models for failure mode classification", i.e. CorLAS-S, CorLAS-T and Battelle models, are applied to the full-scale test dataset described in Section "Full-scale burst tests of pipes containing longitudinal surface cracks" to predict the failure mode of each test specimen. Two scenarios are considered in the analysis: scenario #1 involving using the CorLAS-S and Battelle models to predict σhb and σhr, respectively, and scenario #2 involving using the CorLAS-S and CorLAS-T models to predict σhb and σhr, respectively. Prior to the calculation of the CorLAS-S model, cracks having rectangular profiles are converted to equivalent semi-elliptical profiles by maintaining the same profile area and maximum depth but evaluating the equivalent crack length. On the other hand, actual crack lengths are employed in the CorLAS-T and Battelle models, regardless of the crack profile. The failure modes of 228 tests (126 leaks and 102 ruptures) out of a total 250 tests are predicted. The prediction is not obtained for 22 tests for the following reasons. The CorLAS-S model is inapplicable to three tests in [40] because the ultimate tensile strengths of the specimens are not provided. Solutions of σhb were not obtained due to numerical difficulties when the CorLAS-S model was applied to the six tests reported in [57] and thirteen tests reported in [58]. The predictive performance of the mechanics-based approach corresponding to the two scenarios is presented in Fig. 3 and Table 2. Figure 3 includes the evaluation metrics described in Eqs. (11) to (13), and Table 2 displays the confusion matrix, which is constituted by the four possible types of outcomes of a classifier. Rupture and leak are designated as the positive and negative classes, respectively, in the present study. The bracketed number in the confusion matrices represents the total number of a particular failure mode based on the actual full-scale test data or model predictions.

As indicated in Fig. 3, under both scenarios, the mechanics-based approach results in sensitivity values of over 96% and specificity values of between 20 and 30%. This indicates that the mechanics-based approach is highly accurate in identifying ruptures but has a poor accuracy in identifying leaks. The overall accuracy of the mechanics-based approach is about 55%. Scenario #1 corresponds to a slightly better predictive performance than scenario #2 as the former achieves a higher accuracy and greater balance between the sensitivity and specificity. A possible explanation for the poor accuracy of the mechanics-based approach in identifying leaks is that the CorLAS-S model is relatively accurate in evaluating σhb but the Battelle and CorLAS-T models both markedly underestimate σhr. It follows from the above results that the ML approach is needed to classify ruptures and leaks more accurately.

Machine learning models for failure mode classification

Selection of input features

Based on the results presented in Section "Illustration of mechanics-based approach for failure mode classification", the normalized crack depth and length, a/wt and 2c/(Dwt)0.5, are selected as the input features for the ML models. It must be emphasized that a and 2c are assumed to be the depth and length of a semi-elliptical crack profile; therefore, a non-semi-elliptical crack profile should be converted to an equivalent semi-elliptical profile (see Section "Burst capacity model for surface cracks"). In addition to a/wt and 2c/(Dwt)0.5, two pipe material properties, i.e. σy and Cv, are compounded into a non-dimensional input feature that quantifies the relative resistance to two competing failure mechanisms, i.e. plastic collapse and fracture, of the remaining ligament at the crack, i.e. Ac (wt-a)σy/Cv [30]. Note that (wt-a) σy and Cv/Ac in this compound parameter respectively quantify the resistance of the remaining ligament to plastic collapse and fracture. Figure 4 depicts the failure modes versus any two of the three input features for the 250 test data described in Section "Full-scale burst tests of pipes containing longitudinal surface cracks". Figure 4(a) indicates that leaks tend to occur at deep cracks, which is consistent with the predictions by the mechanics-based approach. However, the correlation between the normalized crack length and failure mode is unclear. Figures 4(b) and (c) suggest that leaks are more likely for pipe specimens with low values of Ac (wt-a)σy/Cv. This confirms the relevance of the input feature Ac (wt-a)σy/Cv.

Model development

The full dataset is randomly divided into 80% and 20% portions, i.e. 200 and 50 data points, as the training and test datasets, respectively. The stratified sampling is employed to generate the training and test datasets; that is, the 80%–20% separation is applied to ruptures and leaks to avoid bias in the two subsets. As such, the training dataset consists of 108 leaks and 92 ruptures, while the test dataset consists of 27 leaks and 23 ruptures.

The five ML algorithms as described in Section "Machine learning classification algorithms" are then respectively applied to the training dataset to establish classifiers. The ten-fold cross validation combined with randomized search [6, 29] is employed to conduct the hyper-parameter tuning for the five algorithms. The value of each hyper-parameter is first randomly selected from a pre-defined range such that a set of values of the hyper-parameters is used to conduct the ten-fold cross validation. We then equally divide the training dataset into ten subsets, employ any nine subsets to train a model with the given set of hyper-parameters and apply the model to the remaining subset to evaluate the model performance. Such a process is repeated ten times such that each subset has been used exactly once for the validation. Model performances on all ten subsets can then be averaged as the final performance of the model corresponding to the given set of hyper-parameters. The set of hyper-parameters that results in the best model performance in the cross validation is then selected as the tuned hyper-parameters. Note that the stratified sampling is also applied to generate each of the ten subsets of the training dataset for the ten-fold cross validation. The predictive performance criterion employed in the cross validation is the accuracy (ACU) as defined in Eq. (13). With a relatively balanced dataset in which the negative class (i.e. leak) accounts for 54%, ACU provides an adequate measure of the predictive accuracy associate with rupture and leak. It is also the most commonly used evaluation metric for classification analysis in pipeline integrity management as indicated in [56].

The ML models in the present study are developed utilizing specialized packages pandas and scikit-learn [53] in the open-source platform Python. The values of the tuned hyper-parameters of the five algorithms are summarized in Table 3. Other hyper-parameters take the default values embedded in scikit-learn. The prior probabilities of both classes (“priors”) in NB are tuned, as the proportions of ruptures and leaks in the training dataset do not necessarily represent those in reality. The Gaussian NB is employed since all three input features are continuous variables. The Gaussian kernel is employed in SVM, and the regularization parameter (C) and kernel coefficient (γG) as described in Section "Support vector machine" are tuned. The tuned hyper-parameters of DT include the maximum number of levels in the tree (max_depth), minimum number of samples required to split a decision node (min_samples_split) and minimum number of samples required in each leaf node (min_samples_leaf). The three tuned hyper-parameters for DT are also employed in RF. In addition, two other hyper-parameters of RF are tuned: the number of trees in the forest (n_estimators) and number of input features to consider for the best split (max_features). The tuned hyper-parameters in GB are the same as those in RF except that max_features is replaced by the learning rate (learning_rate) since all input features are considered at every split of the regression trees in each iteration in GB. The search spaces of all hyper-parameters included in Table 3 that are employed during the hyper-parameter tuning process are provided in Appendix C.

aThe prior probabilities of leak and rupture, respectively.

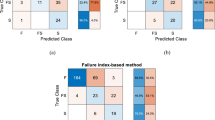

Model performance evaluation

The five ML models developed based on the entire training dataset and tuned hyper-parameters are applied to the test dataset to predict the corresponding failure modes. The sensitivity, specificity and accuracy (see Section "Evaluation metrics of classifier performance") of the predictions given by each ML model on both the training and test datasets are summarized in Fig. 5. The confusion matrices of model predictions for the test dataset are shown in Table 4.

Figure 5 and Table 4 indicate that the five ML models lead to moderately accurate to highly accurate predictions of the failure modes. The predictions by the ML models are more balanced than those by the mechanics-based approach as predictions by the latter have a very low specificity. Among the three single ML algorithms, the Naïve Bayes (NB) performs markedly poorer than the support vector machine (SVM) and the decision tree (DT): NB has an accuracy of around 80% while the other two more than 90%. This could be attributed to that the Gaussian likelihood in NB may not be adequate for the input features. The predictive accuracy of DT is slightly better than SVM. The accuracies of the two ensemble algorithms, i.e. the random forest (RF) and the gradient boosting (GB), are above 95% and somewhat higher than that of DT. The results suggest that the SVM, DT, RF and GB models are highly effective in identifying the failure modes for pipelines containing longitudinal surface cracks. Furthermore, the ensemble ML algorithms are more advantageous than the single ML algorithms.

Feature importance

The feature importance quantifies the impact of a given input feature on the predictive performance of the classifier. DT and DT-based ensemble algorithms can inherently evaluate the importance of each input feature based on GI or mean squared error (MSE), which is employed as the splitting criterion for the construction of trees and forests in DT, RF and GB. The feature importance for a single DT is calculated as the total decrease of GI or MSE caused by the input feature. For DT-based ensembles, the feature importance is the average value of all trees. As such, the importance of the three input features in DT, RF and GB is quantified and shown in Table 5, where the mean and standard deviation of the importance of each feature are obtained by using 100 random states to develop each ML model. A greater mean value in the table indicates a higher importance for the corresponding feature. The random state is a parameter embedded in scikit-learn that guarantees the repeatability of a ML model. This is because DT and DT-based ensemble models could be developed slightly differently across different runs, even with the same hyper-parameters, as the best-found splits of decision nodes may vary across different runs. Therefore, it is valuable to investigate the feature importance of the three ML models under different random states to understand the inherent variability of these models. Results in Table 5 indicate that Ac (wt-a)σy/Cv is the most important input feature in the DT, RF and GB models, followed by a/wt and then 2c/(Dwt)0.5. Such observations are consistent with the discussions based on Fig. 4 (Section "Selection of input features"). The standard deviation of the importance of each input feature for the RF model is larger than that of the same input feature for DT and GB models, but still negligibly small compared with the mean feature importance. This observation implies that when developed at different random states, more variability exists in RF than in DT and GB models. However, such variability of feature importance can still be considered negligible.

Discussions

The results presented in the previous sections demonstrate the advantages of the ML models to predict the failure modes of pipelines containing surface cracks in comparison with the mechanics-based approach. The developed ML models can be readily employed in the fitness-for-service assessment of pipelines containing surface cracks to facilitate the decision making concerning the rehabilitation of in-service pipelines. A few limitations of the investigations should be pointed out. First, the applicability of the five ML models developed in this study is limited by the ranges of the pipe geometric and material properties of the 250 full-scale test data collected. The robustness and applicability of these ML models can be improved by expanding the full-scale test database (depending on the availability of more recent test data in the public domain), in particular those corresponding to high-strength high-toughness pipe specimens. Second, the ML models developed in this study result in a deterministic classification of the failure mode. More sophisticated models can be developed to classify the failure mode probabilistically, which will facilitate the reliability- and risk-based assessment of pipelines containing surface cracks. Finally, the ML models developed in this study are completely data driven and therefore “black-box” models. Engineers may prefer a hybrid between the mechanics-based and machine learning models (i.e. the grey-box model) for improved transparency and interpretability. This is worth exploring in the future.

Conclusions

This study applies the mechanics-based approach and five ML algorithms, including NB, SVM, DT, RF and GB, to predict the failure mode, i.e. leak or rupture, of steel oil and gas pipelines that contain longitudinally oriented surface cracks. The mechanics-based approach classifies the failure mode by comparing the nominal hoop stress remote from the surface crack at failure, σhb, and the remote nominal hoop stress to cause unstable longitudinal propagation of the through-wall crack, σhr. The CorLAS-S model is selected to compute σhb, and the Battelle and CorLAS-T models are selected to compute σhr. Among the five ML algorithms, NB, SVM and DT are single ML algorithms, and the other two are ensemble ML algorithms. Three input features, namely a/wt, 2c/(Dwt)0.5 and Ac (wt-a)σy/Cv, are employed in the ML models.

A total of 250 full-scale burst tests of pipe specimens containing longitudinal surface cracks are collected from the open literature and used to evaluate the predictive performance of these ML algorithms. The analysis results indicate that while the mechanics-based approach is accurate in identifying ruptures, it misclassifies many leaks as ruptures and has an overall accuracy of about 55%. In contrast, all five ML models are markedly more effective than the mechanics-based approach in identifying the failure mode. Among the five models, the predictive accuracy of the two ensemble algorithms, i.e. RF and GB, is the highest with the overall accuracy of over 95% for both the training and test datasets. The accuracy of DT and SVM is only slightly less than that of RF and GB, whereas NB has the lowest accuracy at about 80%. It is observed that Ac (wt-a)σy/Cv is the most important input feature, followed by a/wt and then 2c/(Dwt)0.5, in DT, RF and GB models. This study demonstrates the value of machine learning models for improving the pipeline integrity management practice with respect to cracks.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset of 250 full-scale burst tests of pipe specimens employed in the present study is already included in Appendix B of the manuscript. The source code of the machine learning models developed in the present study will be provided by the corresponding author upon request.

References

Alpaydin E (2020) Introduction to machine learning, 4th edn. The MIT Press, Cambridge

Amano T, Makino H (2012) Evaluation of leak/rupture behavior for axially part-through-wall notched high-strength line pipes. Proceedings of International Pipeline Conference 2012, IPC 2012-90216, Calgary. https://doi.org/10.1115/IPC2012-90216

American Petroleum Institute (2016) API 579–1/ASME FFS-1-fitness for service. API Recommended Practice, New York

Anderson T (2015) Development of a modern assessment method for longitudinal seam weld cracks. PRCI catalogue no. PR-460-134506-R0. Pipeline Research Council International, Chantilly

Anderson T (2017) Assessing crack-like flaws in longitudinal seam welds: a state-of-the-art review. PRCI catalogue no. PR-460-134506-R02. Pipeline Research Council International, Chantilly

Bergstra J, Bengio Y (2012) Random search for hyper-parameter optimization. J Mach Learn Res 13(2):281–305 https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.5555/2188385.2188395

Bramer M (2013) Principles of data mining, 2nd edn. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-4884-5

Breiman L (2001) Random forests. Mach Learn 45(1):5–32. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010933404324

Breiman L, Friedman JH, Olshen RA, Stone CJ (1984) Classification and regression trees. Chapman & Hall/CRC

British Standards Institution (2019) BS7910: Guide to methods for assessing the acceptability of flaws in metallic structures, British Standards Institution, London, UK

Bubbico R (2018) A statistical analysis of causes and consequences of the release of hazardous materials from pipelines. The influence of layout. J Loss Prev Process Ind 56:458–466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlp.2018.10.006

Burges CJ (1998) A tutorial on support vector machines for pattern recognition. Data Min Knowl Disc 2(2):121–167. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009715923555

Carvalho AA, Rebello JMA, Sagrilo LVS, Camerini CS, Miranda IVJ (2006) MFL signals and artificial neural networks applied to detection and classification of pipe weld defects. NDT E Int 39(8):661–667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ndteint.2006.04.003

CEPA (2015) Committed to safety, committed to Canadians: 2015 pipeline industry performance report. Canadian Energy Pipeline Association, Calgary

CEPA (2021) Canadian energy evolving for tomorrow: transmission pipeline industry performance report. Canadian Energy Pipeline Association, Calgary

Cheng YF (2013) Stress corrosion cracking of pipelines, 1st edn. John Wiley & Sons, Inc, Hoboken

Chicco D, Jurman G (2020) The advantages of the Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) over F1 score and accuracy in binary classification evaluation. BMC Genomics 21(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-019-6413-7

Cortes C, Vapnik V (1995) Support-vector networks. Mach Learn 20(3):273–297. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00994018

Cosham A, Hopkins P, Leis B (2012) Crack-like defects in pipelines: the relevance of pipeline-specific methods and standards. Proceedings of International Pipeline Conference 2012, IPC 2012-90459, Calgary. https://doi.org/10.1115/IPC2012-90459

Cravero S, Ruggieri C (2006) Structural integrity analysis of axially cracked pipelines using conventional and constraint-modified failure assessment diagrams. Int J Pressure Vessel Piping 83(8):607–617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpvp.2006.04.004

Cruz FC, Simas Filho EF, Albuquerque MCS, Silva IC, Farias CTT, Gouvea LL (2017) Efficient feature selection for neural network based detection of flaws in steel welded joints using ultrasound testing. Ultrasonics 73:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultras.2016.08.017

DNV GL, 2022. CorLAS™. https://store.veracity.com/corlas (Accessed 25 April 2022)

Dugdale DS (1960) Yielding of steel sheets containing slits. J Mech Phys Solids 8(2):100–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5096(60)90013-2

EDF Energy (2013) R6: assessment of the integrity of the structures containing defects, amendment 10 R6, revision 4, Gloucester, UK

Feng D, Liu Z, Wang X, Jiang Z, Liang S (2020) Failure mode classification and bearing capacity prediction for reinforced concrete columns based on ensemble machine learning algorithm. Adv Eng Inform 45:101126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aei.2020.101126

Folias ES (1964) The stresses in a cylindrical shell containing an axial crack. Int J Fract Mech 1(2):104–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00186748

Friedman JH (2001) Greedy function approximation: a gradient boosting machine. Ann Stat 29(5):1189–1232. https://doi.org/10.1214/aos/1013203451

Guo L, Niffenegger M, Jing Z (2021) Statistical inference and performance evaluation for failure assessment models of pipeline with external axial surface cracks. Int J Press Vessel Pip 194 A:104480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpvp.2021.104480

Hastie T, Tibshirani R, Friedman JH (2009) The elements of statistical learning: data mining, inference, and prediction, 2nd edn. Springer, New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-84858-7

He Z, Zhou W (2022) Improvement of burst capacity model for pipelines containing dent-gouges using Gaussian process regression. Eng Struct 272:115028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2022.115028

Hosseini A, Cronin D, Plumtree A, Kania R (2010) Experimental testing and evaluation of crack defects in line pipe. Proceedings of International Pipeline Conference 2010, IPC 2010-31158, Calgary. https://doi.org/10.1115/IPC2010-31158

James G, Witten D, Hastie T, Tibshirani R (2013) An introduction to statistical learning: with applications in R, 1st edn. Springer, New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-7138-7

Jaske CE, Beavers JA (1996) Effect of corrosion and stress-corrosion cracking on pipe integrity and remaining life. Proceedings of the second international symposium on the mechanical integrity of process piping, St. Louis, MTI Publication No 48, pp 287–297

Jaske CE, Beavers JA (2001) Integrity and remaining life of pipe with stress corrosion cracking. PRCI 186-9709, catalogue no. L51928, Pipeline Research Council International, Falls Church

Jaske CE, Beavers JA (2002) Development and evaluation of improved model for engineering critical assessment of pipelines. Proceedings of International Pipeline Conference 2002, IPC 2002-27027, Calgary. https://doi.org/10.1115/IPC2002-27027

Kawaguchi S, Hagiwara N, Masuda T, Toyoda M (2004) Evaluation of leak-before-break (LBB) behavior for axially notched X65 and X80 line pipes. J Offshore Mech Arctic Eng 126(4):350–357. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.1834619

Kawaguchi S, Hagiwara N, Ohata M, Toyoda M (2004) Modified equation to predict leak/rupture criteria for axially through-wall notched X80 and X100 linepipes having higher Charpy energy. Proceedings of International Pipeline Conference 2004, IPC 2004-322, Calgary. https://doi.org/10.1115/IPC2004-0322

Kiefner JF (2008) Modified equation aids integrity management. Oil Gas J 106(37):78–82

Kiefner JF (2008) Modified ln-secant equation improves failure prediction. Oil Gas J 106(38):64–66

Kiefner JF, Maxey WA, Eiber RJ, Duffy AR (1973) Failure stress levels of flaws in pressurized pipelines, vol ASTM-STP536, pp 461–481. https://doi.org/10.1520/STP49657S

Kumar V, German MD, Shih CF (1981) An engineering approach for elastic-plastic fracture analysis. EPRI Report NP-1931,. Electric Power Research Institute, Palo Alto. https://doi.org/10.2172/6068291

Lam C, Zhou W (2015) Development of probability of ignition model for ruptures of onshore natural gas transmission pipelines. J Pressure Vessel Technol Trans ASME 138(4):041701. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4031812

Lam, C., Zhou, W., 2016. Statistical analyses of incidents on onshore gas transmission pipelines based on PHMSA database. Int J Press Vessel Pip 145: 29–40. hhttps://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpvp.2016.06.003

Leis BN (1992) Ductile fracture and mechanical behavior of typical X42 and X80 line-pipe steels. NG-18 Report No. 204, Pipeline Research Committee of the American Gas Association, Inc, Washington, D.C.

Leis BN, Ghadiali ND (1994) Pipe axial flaw failure criteria PAFFC version 1.0 user’s manual and software. PRCI catalogue no. L51720. Pipeline research council international, Chantilly

Leis BN, Walsh WJ, Brust FW (1990) Mechanical behavior of selected line-pipe steels. NG-18 Report No. 192,. Pipeline Research Committee of the American Gas Association, Inc., Washington, D.C.

Liu B, Hou D, Huang P, Liu B, Tang H, Zhang W, Chen P, Zhang G (2013) An improved PSO-SVM model for online recognition defects in eddy current testing. Nondestruct Test Eval 28(4):367–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/10589759.2013.823608

Maimon OZ, Rokach L (2014) Data mining with decision. Theory and Applications, second ed. World Scientific, Trees. https://doi.org/10.1142/9097

Marani A, Nehdi ML (2020) Machine learning prediction of compressive strength for phase change materials integrated cementitious composites. Constr Build Mater 265:120286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.120286

Maxey WA, Kiefner JF, Eiber RJ, Duffey AR (1972) Ductile fracture initiation, propagation, and arrest in cylindrical vessels. Fracture Toughness. Proceedings of the 1971 National Symposium on Fracture Mechanics, Part II, ASTM STP 514, American Society for Testing and Materials, pp 70–81

Moraes RM, Machado LS (2009) Gaussian naïve bayes for online training assessment in virtual reality-based simulators. Mathware Soft Comput 16(2):123–132

Nessim WA, Zhou W, Zhou J, Rothwell B (2009) Target reliability levels for design and assessment of onshore natural gas pipelines. J Pressure Vessel Technol Transact ASME 131(6):061701. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.3110017

Pedregosa F, Varoquaux G, Michel V, Thirion B, Grisel O, Blondel M, Prettenhofer P, Weiss R, Dubourg V, Vanderplas J, Passos A, Cournapeau D, Brucher M, Perrot M, Duchesnay E (2011) Scikit-learn: machine learning in Python. J Mach Learn Res 12:2825–2830

PHMSA, 2019. Pipeline safety: safety of gas transmission pipelines. Docket no. PHMSA-2011-0023

Polasik S, Jaske CE, Bubenik TA (2016) Review of engineering fracture mechanics model for pipeline applications. Proceedings of 2016 international pipeline conference. IPC 2016-64605, Calgary. https://doi.org/10.1115/IPC2016-64605

Rachman A, Zhang T, Ratnayake RC (2021) Applications of machine learning in pipeline integrity management: a state-of-the-art review. Int J Press Vessel Pip 193:104471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpvp.2021.104471

Rana MD, Rawls GB (2007) Prediction of fracture stresses of high pressure gas cylinders containing cracklike flaws. J Press Vessel Technol 129(4): 639–643. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.2767346

Rana MD, Selines RJ (1988) Structural integrity assurance of high-strength steel gas cylinders using fracture mechanics. Eng Fract Mech 30(6):877–894. https://doi.org/10.1016/0013-7944(88)90147-6

Rana MD, Smith JH, Tribolet RO (1997) Technical basis for flawed cylinder test specification to assure adequate fracture resistance of ISO high-strength steel cylinder. J Press Vessel Technol 119(4):475–480. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.2842332

Rothwell AB, Coote RI (2009) A critical review of assessment methods for axial planar surface flaws in pipe. In: Proceedings of the international conference on pipeline technology 2009, Ostend, Belgium.

Shannon RWE (1974) The failure behaviour of line pipe defects. Int J Press Vessel Pip 2:243–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/0308-0161(74)90006-4

Shih CF, Hutchinson JW (1975) Fully plastic solutions and large scale yielding estimates for plane stress crack problems. In: Report no. DEAP S-14. Harvard University, Cambridge

Staat M (2004) Plastic collapse analysis of longitudinally flawed pipes and vessels. Nucl Eng Des 234(1–3):25–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nucengdes.2004.08.002

Yan J, Zhang S, Kariyawasam S, Pino M, Liu T (2018) Validate crack assessment models with in-service and hydrotest failures. In: Proceedings of international pipeline conference, IPC 2018–78251, Calgary. https://doi.org/10.1115/IPC2018-78251

Yan Z, Zhang S, Zhou W (2014) Model error assessment of burst capacity models for energy pipelines containing surface cracks. J Pressure Vessels Piping 120-121:80–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpvp.2014.05.007

Yan J, Zhang S, Kariyawasam S, Lu D, Matchim T (2020) Reliability-based crack threat assessment and management. In: Proceedings of international pipeline conference, IPC 2020–9484. Online, Virtual. https://doi.org/10.1115/IPC2020-9484

Zadkarami M, Shahbazian M, Salahshoor K (2016) Pipeline leakage detection and isolation: an integrated approach of statistical and wavelet feature extraction with multi-layer perception neural network (MLPNN). J Loss Prev Process Ind 43:479–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlp.2016.06.018

Zadkarami M, Shahbazian M, Salahshoor K (2017) Pipeline leak diagnosis based on wavelet and statistical features using Dempster-Shafer classifier fusion technique. Process Saf Environ Prot 105:156–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2016.11.002

Zhou W, Xiang W, Cronin D (2016) Probability of rupture model for corroded pipelines. Int J Press Vessel Pip 147:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpvp.2016.10.001

Acknowledgements

The financial support provided by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) through the Discovery Grant (Grant No. RGPIN-2019-05160) is gratefully acknowledged. The financial support provided to HS by the Faculty of Engineering at the University of Western Ontario is also acknowledged. The constructive comments from the anonymous reviewers are greatly appreciated.

Funding

Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Grant (Grant No. RGPIN-2019-05160) for WZ.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sun, H.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Acquisition, Investigation, Writing – Original Draft, Visualization. Zhou, W.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Reviewing and Editing, Supervision, Funding Acquisition. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A

Equations for calculating J t and J tT in the CorLAS-S and CorLAS-T models

The equation for calculating Jt in the CorLAS-S model is:

where Je and Jp are the elastic and plastic component of Jt, respectively. The equation for calculating JtT in the CorLAS-T model is:

where JeT and JpT are the elastic and plastic component of JtT, respectively. JeT and JpT are based on the stress intensity factor solution for through-wall cracks and Kumar et al. [41]. In Eqs. (A.1) and (A.2), Qsf is the flaw shape factor given by:

Fsf is the free surface factor given by:

f3(n) is the Shih and Hutchinson [62] factor given by:

n is the strain hardening exponent [44, 46] that can be calculated by:

and εp is the plastic strain corresponding to σl for API steel given by:

Note that 2c in Eqs. (A.3) and (A.4) represents the (equivalent) semi-elliptical crack length.

Appendix B

Table 6

Appendix C

Table 7

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, H., Zhou, W. Classification of failure modes of pipelines containing longitudinal surface cracks using mechanics-based and machine learning models. J Infrastruct Preserv Resil 4, 5 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43065-022-00062-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43065-022-00062-5