Abstract

Background

Several studies have assessed whether physical activity interventions can reduce substance use in young people at risk of problematic substance use. This report identifies and describes the reporting of implementation characteristics within published studies of physical activity interventions for young people at risk of problematic substance use and provides recommendations for future reporting.

Methods

Reported implementation strategies (including intervention manualization), barriers, implementation fidelity, and personnel acceptance were extracted from studies of physical activity interventions for young people aged 12–25 years at risk of problematic substance use that were included in a previous systematic review of intervention efficacy.

Results

Implementation strategies were reported in less than half of the included studies (42.9%), implementation barriers in only 10.7% of studies, intervention fidelity in 21.4%, and personnel acceptance in a single study (3.6%).

Conclusions

Results indicate insufficient reporting of implementation strategies, barriers, fidelity, and personnel acceptance. Consideration of implementation characteristics is essential for implementing physical activity interventions in practice. Inadequate or limited reporting of these characteristics may contribute to delayed uptake and adoption of evidence-based interventions in clinical practice. Recommendations to improve the reporting of implementation information include integrating standards for reporting implementation characteristics into existing reporting guidelines, developing an international taxonomy of implementation strategies, and upskilling intervention researchers in the fundamentals of implementation science.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Adolescence and early adulthood, particularly the age group 12–25 [1], are peak periods for the emergence of psychiatric conditions and problematic substance use [2,3,4]. Problematic substance use and comorbid mental ill-health onsetting during this key developmental period pose critical risk factors for impaired life trajectories [2].

Physical activity (PA) and physical activity interventions represent one promising approach for early intervention for problematic substance use in young people [5, 6]. As the age range of 12–25 years is generally characterized by a decline in activity levels [7, 8], and more than 80% of young people currently do not reach recommended physical activity levels [9,10,11], this approach may also have benefits beyond substance use.

Early intervention and treatment are crucial to mitigate long-term consequences of substance use, mental ill-health, and sedentary behaviors in young people. Physical activity interventions have shown a beneficial effect on young people’s mental and physical health including substance use behavior [5, 12]; however, they are rarely implemented into practice [13].

To improve the uptake of physical activity interventions in clinical practice, a range of factors need to be considered and addressed. One way to support the uptake of physical activity interventions into practice is to ensure that essential implementation information—including implementation strategies and barriers that have been applied or identified within trialed interventions—is routinely reported in published studies. Shortcomings in reporting of essential implementation information reduce the likelihood that these interventions will be taken up in practice if proven effective (see also Rudd et al. [14]). Reporting strategies that were used to improve implementation, or barriers encountered in the respective study settings, could be used to inform further PA implementation studies, provide useful information for decision-makers, expedite the process of uptake and implementation of effective physical activity interventions into clinical practice, and thus reduce the time from research to public health impact [14, 15]. For this reason, integrating implementation thinking and implementation strategy into intervention studies should be a research priority within both PA intervention research, but also intervention research overall. Previous research indicates that less than 50% of effective interventions are being implemented into health services, and many face decades of delays from initial evidence to their implementation [16] which leads to delays in these interventions being available to individuals [17].

Although often considered the domain of implementation trials, the entire efficacy-effectiveness-implementation research spectrum may benefit from reporting of implementation factors and integration of discrete implementation strategies. Failure to consider implementation strategies from study initiation commonly leads to unplanned mid-course corrections [16]. Integrating implementation considerations early in the research process, as part of efficacy trials, may reduce these unplanned mid-course corrections, increase intervention fidelity, streamline progression to effectiveness research and subsequent implementation [18], and accelerate an intervention’s progression through the research spectrum.

To date, reviews of physical activity interventions for problematic substance use in young people have only considered the efficacy of interventions, rather than factors related to implementation. This report aimed to examine implementation strategies and barriers, implementation fidelity and acceptance of interventions among non-research personnel, and thus to highlight the importance of reporting implementation factors. The findings of this report will inform attempts to improve the reporting of intervention factors in future trials of physical activity interventions for young people at risk of problematic substance use and accelerate the uptake of evidence-based interventions into practice.

Method

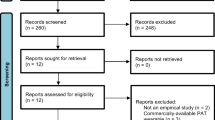

A systematic review of the effects of physical activity interventions was conducted between Nov 2020–Jan 2021 and updated in Nov 2022 [5]. Study eligibility was based on the intervention of interest (physical activity interventions including multimodal and acute studies applying cognitive, behavioral, and informational approaches), population of interest (young people aged 12–25 at risk of problematic substance use, defined as substance use that is associated with health and/or social problems and/or legal problems), outcomes of interest (substance use, physical activity, mental health), language (English), and study design (randomized-controlled trials (RCT) and non-RCT). The review included different formats and intervention approaches, including efficacy and effectiveness studies, and unimodal and multimodal approaches to provide a comprehensive review of existing evidence on physical activity interventions in this population. This report is a complimentary piece to Klamert et al. [5].

Due to the lack of international consensus regarding what comprises “critical” implementation characteristics, factors referring to implementability of healthcare interventions as reported by Klaic et al. [19] were extracted. These included implementation strategies (including sustainability and feasibility if reported), barriers (e.g., implementation context), implementation fidelity, and acceptance of the interventions among non-research personnel (for definitions see Table 1). Extracted implementation strategies were aligned with the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project, a compilation of internationally recognized implementation strategies [20]. Implementation barriers, implementation fidelity, and personnel acceptance were mapped onto the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR), a practical framework allowing the systematic assessment of implementation barriers and facilitators [21].

The report aimed to provide a brief overview of individual and service level factors associated with the implementability of healthcare interventions to highlight existing shortcomings, and the need for advancements in reporting standards relating to physical activity interventions for young people with substance use.

Results

Twenty-eight studies were included in the review. Most of the interventions (92.9%) were delivered in educational or community settings. One or more implementation strategies were reported in 42.9% of the included studies (12/28), while 10.7% of the studies (3/28) reported one or more implementation barriers, 21.4% of studies reported on implementation fidelity (6/28), and 3.6% of studies (1/28) reported on acceptance of the intervention among involved non-research personnel.

Ninety-four percent of the extracted implementation strategies could be mapped onto 16 strategies included in the ERIC project. Fifty-seven implementation strategies included under the ERIC framework were not reported in any included study. The most frequently reported ERIC implementation strategies were conduct ongoing training (for peers, coaches, and staff) (25%, 7/28 studies) and change service sites (change service location to increase access) (14.3%, 4/28 studies). Five studies (17.9%) reported the development of manuals (i.e., develop education materials according to ERIC) based on the intervention or intervention elements. Two extracted strategies could not be assigned to ERIC implementation strategies (i.e., division of facilitation workload across multiple individuals to minimize facilitation burden).

Only four studies (14.3%) assessed implementation barriers and facilitators in line with proposed CFIR constructs, which are thought to be essential to the successful implementation of interventions. The most frequently assessed barriers were location conditions (Outer setting domain, assessed by 7.1%, 2/28 studies). Other barriers assessed included local attitudes (3.6%, 1/28 studies), critical incidents (3.6%, 1/28 studies), and innovation deliverers (3.6%, 1/28 studies). Implementation facilitators (personnel acceptance) were only reported in one included study. Forty-two essential implementation constructs according to the CFIR were not assessed in any study. For detailed implementation characteristics and their mapping onto ERIC and the CFIR, see Supplementary Table 1. For the pattern of reported implementation characteristics, see Table 2.

Discussion

This report outlines the reporting of implementation factors, including strategies, barriers, fidelity, and personnel acceptance, within studies of physical activity interventions for young people at heightened risk of problematic substance use. Extracted implementation factors were mapped onto existing implementation-focused systems and frameworks (ERIC, CFIR). Based on an efficacy-effectiveness review conducted by Klamert et al. [5], the reported implementation factors were extracted from 28 included studies. The review found that ERIC implementation strategies were under-reported as part of PA interventions; less than half of the identified studies reported implementation strategies that were used as part of the interventions. Implementation knowledge, which is essential to the successful implementation of an intervention according to the CFIR framework, such as implementation barriers, was only reported by just over a 10th of included studies. Implementation fidelity was reported by roughly one quarter. While the investigated studies included PA intervention studies only, findings of under-reporting may apply to other types of interventions more broadly, as indicated by an ongoing separation (rather than integration) of intervention development and implementation knowledge in healthcare research.

There was an overlap in extracted strategies with previous findings reported within the implementation of health interventions. This overlap included ongoing training courses in intervention delivery [59, 60], the use of train-the-trainer strategies, and accessing new funding [20, 59, 60]. Additional implementation strategies—not employed in studies covered in this review—have been identified in the literature more broadly [20].

Reported implementation barriers in this report aligned with those identified by Langley et al. [61] and Josyula and Lyle [62], namely, local conditions and attitudes (e.g., cultural environment) and increased workload on clinicians and administration as barriers (CFIR constructs: implementation team members, work infrastructure).

With reporting on personnel or provider acceptance limited to a single study, it was not possible to meaningfully compare findings with previous research evidence. Overall, personnel acceptance of and attitudes toward the implementation of evidence-based interventions have not been well studied within the international context [63].

Poor reporting of implementation strategies as part of research studies reduces the chances of evidence-based interventions being taken up into routine care and limits conclusions that can be drawn by decision-makers regarding the trialed interventions [16, 22].

One factor contributing to underreporting of implementation as part of intervention descriptions, but also impeding a priori integration of implementation considerations, is the inconsistent use of implementation terminology, even within the field of implementation science [64]. Consensus building and standardization of terms are essential to streamlining communication in these emerging fields [65, 66] and to the dissemination of implementation knowledge in research and practice [65]. Several attempts to develop international taxonomies of published implementation strategies [20, 67, 68], measure the effectiveness of individual strategies [69], and assess tailored implementation strategies for different contexts have been undertaken [20]. However, implementation strategies must not be just reported, but also “adequately reported,” i.e., reported in sufficient detail to allow for measurement and reproducibility of the strategy and/or its components in research or practice [22], to be useful and allow real-world application [70, 71].

Another factor contributing to poor reporting of implementation strategies may be the limited training of researchers studying new interventions in implementation science and the lack of direct consultation or collaboration of research teams investigating new health interventions with skilled implementation researchers (see also [72]). Proctor et al. [72] argue that this is due to the emerging nature of the field of implementation science, which continues to struggle with conceptual and methodological challenges.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this report. Studies included were predominantly set in educational or community settings. For this reason, it is unclear whether the information extracted can be generalized to clinical settings.

Further, based on the shortcomings in reporting implementation characteristics in included studies, resulting in the extraction of only a small number of implementation characteristics, authors were not able to draw any conclusions regarding the effectiveness of reported implementation strategies and their impact on intervention success. Additionally, the authors’ decision to focus on a framework relating to the implementability may entail the exclusion of other implementation characteristics that are seen as relevant by other members of the scientific community.

Recommendations

Based on current and previous evidence of underreporting of implementation characteristics in physical activity interventions for young people at risk of problematic substance use, we suggest the following recommendations for future research on PA interventions, but also healthcare interventions more broadly:

-

1.

Upskill intervention researchers in the field of implementation. This could increase the likelihood of implementation considerations being included in the early stages of intervention development. A priori considerations in the early stages of research regarding the streamlining of evidence-based interventions from efficacy testing to implementation would likely lead to faster availability of effective interventions to clients.

-

2.

Strengthen linkages between the fields of intervention research and implementation science through strong networks and multidisciplinary teams. While implementation science has developed from a need for effective interventions and treatments to be streamlined to clinical practice, both fields operate mostly independently with neither benefiting from discoveries in the respective other field in a timely manner.

-

3.

Establish collaborations with and recruiting health care practitioners and relevant personnel (i.e., intervention facilitators) as research team members ([73], see also [74]).

-

4.

Integrate existing taxonomies of implementation strategies subject to international consensus to decrease inconsistent terminology within the fields of implementation science.

-

5.

Integrate reporting guidelines (including strategies, barriers, fidelity) (see also [22, 75]) into existing, internationally recognized reporting guidelines and checklists, such as the Template for intervention description and replication checklist (TIDieR) [13].

-

6.

Establish implementation strategy as a research priority rather than a research addition or extension in the field of intervention development.

Conclusion

There is limited reporting of implementation characteristics (including implementation strategies, barriers, intervention fidelity, and acceptance of interventions among non-research personnel) in studies of physical activity interventions for young people at heightened risk of problematic substance use. The underreporting may be related to several issues, including inconsistent implementation terminology, limited (a priori) integration of implementation considerations in intervention development, a limited number of researchers who are skilled in both implementation science and intervention development, and the absence of reporting standards for implementation characteristics. Exploration of these issues may reduce the underreporting of implementation characteristics in future publications.

Several recommendations to reduce underreporting and increase consideration of implementation characteristics as part of PA intervention research, but also healthcare intervention research overall have been made, including the development of internationally recognized standards for the reporting of implementation characteristics. Increased, high-quality reporting of this information is one factor that will likely contribute towards increasing the uptake of effective physical activity interventions in practice and streamlining intervention development from efficacy testing to implementation.

Availability of data and materials

The data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional file or available upon request from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- PA:

-

Physical activity

References

McGorry PD, Purcell R, Hickie IB, Jorm AF. Investing in youth mental health is a best buy. Med J Aust. 2007;187(Supplement 7):5–7.

Degenhardt L, Stockings E, Patton G, Hall WD, Lynskey M. The increasing global health priority of substance use in young people. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(3):251–64.

Hall WD, Patton G, Stockings E, Weier M, Lynskey M, Morley KI, et al. Why young people’s substance use matters for global health. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(3):265–79.

Chaplin TM, Niehaus C, Goncalves SF. Stress reactivity and the developmental psychopathology of adolescent substance use. Neurobiology Stress. 2018;9:133–9.

Klamert L, Bedi G, Craike M, Kidd S, Pascoe M, Parker AG. Physical activity interventions for young people with increased risk of problematic substance use: a systematic review including different intervention formats. Mental Health and Physical Activity. 2023;25:100551.

Simonton AJ, Young CC, Johnson KE. Physical activity interventions to decrease substance use in youth: a review of the literature. Subst Use Misuse. 2018;53(12):2052–68.

Allison KR, Adlaf EM, Dwyer JJM, Lysy DC, Irving HM. The decline in physical activity among adolescent students: a cross-national comparison. Can J Public Health. 2007;98(2):97–100.

Finne E, Bucksch J, Lampert T, Kolip P. Age, puberty, body dissatisfaction, and physical activity decline in adolescents. Results of the German health interview and examination survey (KiGGS). Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:1–14.

Guthold R, Stevens GA, Riley LM, Bull FC. Global trends in insufficient physical activity among adolescents: a pooled analysis of 298 population-based surveys with 1·6 million participants. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(1):23–35.

Hallal PC, Andersen LB, Bull FC, Guthold R, Haskell W, Ekelund U. Global physical activity levels: surveillance progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Lancet. 2012;380(9838):247–57.

Aubert S, Brazo-Sayavera J, Gonzalez SA, Janssen I, Manyanga T, Oyeyemi AL, et al. Global prevalence of physical activity for children and adolescents; inconsistencies, research gaps, and recommendations: a narrative review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2021;18(1):81.

Linke SE, Ussher M. Exercise-based treatments for substance use disorders: evidence, theory, and practicality. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2015;41(1):7–15.

Hoffmann T, Glasziou P, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348:1–12.

Rudd BN, Davis M, Beidas RS. Integrating implementation science in clinical research to maximize public health impact: a call for the reporting and alignment of implementation strategy use with implementation outcomes in clinical research. Implement Sci. 2020;15(1):1–11.

Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care. 2012;50(3):217–26.

Bauer MS, Kirchner J. Implementation science: what is it and why should I care? Psychiatry Res. 2020;283:1–6.

Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP, Lavis JN, Hill SJ, Squires JE. Knowledge translation of research findings. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):1–17.

French CT, Diekemper RL, Irwin RS, Chest Expert Cough Panel. Assessment of intervention fidelity and recommendations for researchers conducting studies on the diagnosis and treatment of chronic cough in the adult: chest guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2015;148(1):32–54.

Klaic M, Kapp S, Hudson P, Chapman W, Denehy L, Story D, et al. Implementability of healthcare interventions: an overview of reviews and development of a conceptual framework. Implement Sci. 2022;17(1):10.

Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, Damschroder LJ, Smith JL, Matthieu MM, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implementation Sci. 2015;10:21.

Damschroder LJ, Reardon CM, Widerquist MAO, Lowery J. The updated Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research based on user feedback. Implemention Sci. 2022;17(1):75.

Proctor EK, Powell BJ, McMillen JC. Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):1–11.

National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. Effective implementation: Core components, adaptation, and strategies. Fostering healthy mental, emotional, and behavioral development in children and youth: A national agenda. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington (DC): The National Academic Press; 2019.

Bach-Mortensen AM, Lange BCL, Montgomery P. Barriers and facilitators to implementing evidence-based interventions among third sector organisations: A systematic review. Implement Science. 2018;13(1):1–19.

Breitenstein SM, Gross D, Garvey CA, Hill C, Fogg L, Resnick B. Implementation fidelity in community-based interventions. Res Nurs Health. 2010;33(2):164–73.

Flanagan ME, Ramanujam R, Doebbeling BN. The effect of provider- and workflow-focused strategies for guideline implementation on provider acceptance. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):1–10.

Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38(2):65–76.

An LC, Demers MR, Kirch MA, Considine-Dunn S, Nair V, Dasgupta K, et al. A randomized trial of an avatar-hosted multiple behavior change intervention for young adult smokers. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2013;2013(47):209–15.

Correia CJ, Benson TA, Carey KB. Decreased substance use following increases in alternative behaviors: A preliminary investigation. Addict Behav. 2005;30(1):19–27.

Daniel JZ, Cropley M, Fife-Schaw C. Acute exercise effects on smoking withdrawal symptoms and desire to smoke are not related to expectation. Psychopharmacol. 2007;195(1):125–9.

Daniel JZ, Cropley M, Fife-Schaw C. The effect of exercise in reducing desire to smoke and cigarette withdrawal symptoms is not caused by distraction. Addiction. 2006;101(8):1187–92.

Everson ES, Daley AJ, Ussher M. Does exercise have an acute effect on desire to smoke, mood and withdrawal symptoms in abstaining adolescent smokers? Addict Beh. 2006;31(9):1547–58.

Everson ES, Daley AJ, Ussher M. The effects of moderate and vigorous exercise on desire to smoke, withdrawal symptoms and mood in abstaining young adult smokers. Mental Health and Physical Activity. 2008;1(1):26–31.

Faulkner GE, Arbour-Nicitopoulos KP, Hsin A. Cutting down one puff at a time: The acute effects of exercise on smoking behaviour. Journal of Smoking Cessation. 2010;5(2):130–5.

Fishbein D, Miller S, Herman-Stahl M, Williams J, Lavery B, Markovitz L, et al. Behavioral and psychophysiological effects of a yoga intervention on high-risk adolescents: A randomized control trial. J Child Fam Stud. 2016;25(2):518–29.

Ho JY, Kraemer WJ, Volek JS, Vingren JL, Fragala MS, Flanagan SD, et al. Effects of resistance exercise on the HPA axis response to psychological stress during short-term smoking abstinence in men. Addict Behav. 2014;39(3):695–8.

Blank MD, Ferris KA, Metzger A, Gentzler A, Duncan C, Jarrett T, et al. Physical activity and quit motivation moderators of adolescent smoking reduction. Am J Health Behav. 2017;41(4):419–27.

Horn K, Branstetter S, Zhang J, Jarrett T, Tompkins NO, Anesetti-Rothermel A, et al. Understanding physical activity outcomes as a function of teen smoking cessation. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53(1):125–31.

Horn K, Dino G, Branstetter SA, Zhang J, Noerachmanto N, Jarrett T, et al. Effects of physical activity on teen smoking cessation. Pediatrics. 2011;128(4):801–11.

Janse Van Rensburg K, Taylor AH. The effects of acute exercise on cognitive functioning and cigarette cravings during temporary abstinence from smoking. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental. 2008;23(3):193–9.

Kerr JC, Valois RF, Farber NB, Vanable PA, Diclemente RJ, Salazar L, et al. Effects of promoting health among teens on dietary, physical activity and substance use knowledge and behaviors for african american adolescents. Am J Health Educ. 2013;44(4):191–202.

Lane DJ, Lindemann DF, Schmidt JA. A comparison of computer-assisted and self-management programs for reducing alcohol use among students in first year experience courses. J Drug Educ. 2012;42(2):119–35.

Melamed O, Voineskos A, Vojtila L, Ashfaq I, Veldhuizen S, Dragonetti R, et al. Technology-enabled collaborative care for youth with early psychosis: Results of a feasibility study to improve physical health behaviours. Early Intervention in Psychiatry. 2022;16(10):1143–51.

Murphy TJ, Pagano RR, Marlatt GA. Lifestyle modification with heavy alcohol drinkers: Effects of aerobic exercise and meditation. Addict Behav. 1986;11(2):175–86.

Oh H, Taylor AH. Self-regulating smoking and snacking through physical activity. Health Psychology. 2014;33(4):349–59.

Parker AG, Hetrick SE, Jorm AF, Mackinnon AJ, McGorry PD, Yung AR, et al. The effectiveness of simple psychological and physical activity interventions for high prevalence mental health problems in young people: A factorial randomised controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2016;196:200–9.

Prapavessis H, De Jesus S, Harper T, Cramp A, Fitzgeorge L, Mottola MF, et al. The effects of acute exercise on tobacco cravings and withdrawal symptoms in temporary abstinent pregnant smokers. Addict Behav. 2014;39(3):703–8.

Prince MA, Collins RL, Wilson SD, Vincent PC. A preliminary test of a brief intervention to lessen young adults' cannabis use: Episode-level smartphone data highlights the role of protective behavioral strategies and exercise. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2020;28(2):150–6.

Rotheram-Borus M, Tomlinson M, Durkin A, Baird K, DeCelles J, Swendeman D. Feasibility of using soccer and job training to prevent drug abuse and HIV. AIDS and Behavior. 2016;20(9):1841–50.

Scott KA, Myers AM. Impact of fitness training on native adolescents' self-evaluations and substance use. Can J Public Health. 1988;79(6):424–9.

Stanley ZD, Asfour LW, Weitzman M, Sherman SE. Implementation of a peer-mediated health education model in the United Arab Emirates: Addressing risky behaviours among expatriate adolescents. East Mediterr Health J. 2017;23(7):480–5.

Taylor A, Katomeri M, Ussher M. Effects of walking on cigarette cravings and affect in the context of Nesbitt’s paradox and the circumplex model. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2006;28(1):18–31.

Taylor AH, Katomeri M, Ussher M. Acute effects of self-paced walking on urges to smoke during temporary smoking abstinence. Psychopharmacol. 2005;181(1):1–7.

Tesler R, Plaut P, Endvelt R. The effects of an urban forest health intervention program on physical activity, substance abuse, psychosomatic symptoms, and life satisfaction among adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(10):1–12.

Weinstock J, Capizzi J, Weber SM, Pescatello LS, Petry NM. Exercise as an intervention for sedentary hazardous drinking college students: A pilot study. Mental Health and Physical Activity. 2014;7(1):55–62.

Wilson SD, Collins RL, Prince MA, Vincent PC. Effects of exercise on experimentally manipulated craving for cannabis: A preliminary study. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2018;26(5):456–66.

Weinstock J, Petry NM, Pescatello LS, Henderson CE. Sedentary college student drinkers can start exercising and reduce drinking after intervention. Psychol Addict Behav. 2016;30(8):791–801.

Ybarra ML, Holtrop JS, Prescott TL, Rahbar MH, Strong D. Pilot RCT results of stop my smoking USA: A text messaging-based smoking cessation program for young adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(8):1388–99.

Hoekstra F, Hoekstra T, van der Schans CP, Hettinga FJ, van der Woude LHV, Dekker R, et al. The implementation of a physical activity counseling program in rehabilitation care: Findings from the ReSpAct study. Disabil Rehabil. 2021;43(12):1710–21.

Forman SG, Olin SS, Hoagwood KE, Crowe M, Saka N. Evidence-based interventions in schools: developers’ views of implementation barriers and facilitators. Sch Ment Heal. 2008;1(1):26–36.

Langley AK, Nadeem E, Kataoka SH, Stein BD, Jaycox LH. Evidence-based mental health programs in schools: barriers and facilitators of successful implementation. Sch Ment Heal. 2010;2(3):105–13.

Josyula LK, Lyle RM. Barriers in the implementation of a physical activity intervention in primary care settings: lessons learned. Health Promot Pract. 2013;14(1):81–7.

Aarons GA, Sawitzky AC. Organizational culture and climate and mental health provider attitudes toward evidence-based practice. Psychol Serv. 2004;3(1):61–72.

Rabin BA, Brownson RC. Terminology for dissemination and implementation research. In: Browson RC, Graham AC, Proctor EK, editors. Dissemination and implementation research in health: Translating science to practice: Oxford University Press; 2018.

Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, Straus SE, Tetroe J, Caswell W, et al. Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006;26(1):13–24.

McKibbon KA, Lokker C, Wilczynski NL, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, Davis DA, et al. A cross-sectional study of the number and frequency of terms used to refer to knowledge translation in a body of health literature in 2006: a Tower of Babel? Implement Sci. 2010;5(16):1–11.

Mazza D, Bairstow P, Buchan H, Chakraborty SP, Van Hecke O, Grech C, et al. Refining a taxonomy for guideline implementation: results of an exercise in abstract classification. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):1–10.

Powell BJ, McMillen JC, Proctor EK, Carpenter CR, Griffey RT, Bunger AC, et al. A compilation of strategies for implementing clinical innovations in health and mental health. Med Care Res Rev. 2012;69(2):123–57.

Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). EPOC taxonomy. Cochrane. 2015.

Albrecht L, Archibald M, Arseneau D, Scott SD. Development of a checklist to assess the quality of reporting of knowledge translation interventions using the Workgroup for Intervention Development and Evaluation Research (WIDER) recommendations. Implement Sci. 2013;8:1–5.

Michie S, Fixsen D, Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP. Specifying and reporting complex behaviour change interventions: the need for a scientific method. Implement Sci. 2009;4:1–6.

Proctor EK, Landsverk J, Aarons G, Chambers D, Glisson C, Mittman B. Implementation research in mental health services: An emerging science with conceptual, methodological, and training challenges. Adm Policy Mental Health Metal Health Serv Res. 2009;36(1):24–34.

Wathen CN, MacMillan HL. The role of integrated knowledge translation in intervention research. Prev Sci. 2018;19(3):319–27.

Tabak RG, Padek MM, Kerner JF, Stange KC, Proctor EK, Dobbins MJ, et al. Dissemination and implementation science training needs: insights from practitioners and researchers. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(3):322–9.

Pinnock H, Barwick M, Carpenter CR, Eldridge S, Grandes G, Griffiths CJ, et al. Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI) Statement. BMJ. 2017;356:i6795.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received for this review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LK conceived of the review; designed the search strategy; completed the systematic search, screening phases, study selection, data extraction, bias assessment, and data synthesis; and wrote the initial manuscript. AP, MC, SK, and MP provided valuable guidance and input regarding the review conceptualization and performed screening, study selection, data extraction, and bias assessment in duplicate. AP, MC, GB, and SK provided guidance, critical appraisal, and expertise to this manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Supplementary Table 1. Detailed implementation characteristics of included studies.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Klamert, L., Craike, M., Bedi, G. et al. Underreporting of implementation strategies and barriers in physical activity interventions for young people at risk of problematic substance use: a brief report. Implement Sci Commun 5, 45 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-024-00578-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-024-00578-9