Abstract

Background

Implementation science researchers often cite clinical champions as critical to overcoming organizational resistance and other barriers to the implementation of evidence-based health services, yet relatively little is known about who champions are or how they effect change. To inform future efforts to identify and engage champions to support HPV vaccination, we sought to describe the key characteristics and strategies of vaccine champions working in adolescent primary care.

Methods

In 2022, we conducted a national survey with a web-based panel of 2527 primary care professionals (PCPs) with a role in adolescent HPV vaccination (57% response rate). Our sample consisted of pediatricians (26%), family medicine physicians (22%), advanced practice providers (24%), and nursing staff (28%). Our survey assessed PCPs’ experience with vaccine champions, defined as health care professionals “known for helping their colleagues improve vaccination rates.”

Results

Overall, 85% of PCPs reported currently working with one or more vaccine champions. Among these 2144 PCPs, most identified the champion with whom they worked most closely as being a physician (40%) or nurse (40%). Almost all identified champions worked to improve vaccination rates for vaccines in general (45%) or HPV vaccine specifically (49%). PCPs commonly reported that champion implementation strategies included sharing information (79%), encouragement (62%), and vaccination data (59%) with colleagues, but less than half reported that champions led quality improvement projects (39%). Most PCPs perceived their closest champion as being moderately to extremely effective at improving vaccination rates (91%). PCPs who did versus did not work with champions more often recommended HPV vaccination at the earliest opportunity of ages 9–10 rather than later ages (44% vs. 33%, p < 0.001).

Conclusions

Findings of our national study suggest that vaccine champions are common in adolescent primary care, but only a minority lead quality improvement projects. Interventionists seeking to identify champions to improve HPV vaccination rates can expect to find them among both physicians and nurses, but should be prepared to offer support to more fully engage them in implementing interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Implementation science research emphasizes the importance of clinical champions in scaling up the implementation of evidence-based health services. According to the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC), champions are “individuals who dedicate themselves to supporting, marketing, and driving through an implementation, overcoming indifference or resistance that the intervention may provoke in an organization” [1]. Champions are characterized by their persistence, enthusiasm, and conviction in pushing implementations forward, even when it means putting their reputations on the line [2]. They differ from related concepts, such as “opinion leaders,” who more passively exert an influence on the flow of information within networks [3]. In this way, champions constitute an implementation strategy in and of themselves [1], while also having robust potential to effectively deliver training and other support to improve the provision of evidence-based services within clinics and larger health care systems. Perhaps not surprisingly, interventions in clinical settings commonly feature a champion component [2, 4,5,6].

Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination is a useful case study for investigating the role of champions. Widespread HPV vaccination could prevent over 90% of the nearly 36,500 HPV cancers diagnosed in the United States each year [7]. Unfortunately, despite national recommendations for adolescents to receive the two-dose HPV vaccine series between ages 9 and 12, only 50% of 13-year-olds were fully vaccinated in 2021, with consistently lower coverage in rural areas [8, 9]. Importantly, younger age at initiation of the HPV vaccine series is associated with higher rates of on-time series completion [10]. The reasons for low uptake are complex, but one key factor is primary care professionals’ (PCPs’) infrequent and ineffective recommendation of HPV vaccination [11,12,13]. Evidence-based implementation strategies that combine provider communication training, assessment and feedback, and other techniques are emerging to improve HPV vaccination within health care settings [14,15,16]. Given their role as change agents, training champions to use these implementation strategies could help address challenges with scaling routine HPV vaccination across health care systems.

Despite the implementation research literature consistently emphasizes the critical importance of champions, relatively little work has provided insight into how to identify and engage champions to best meet implementation needs. For example, no prior studies have examined the extent to which champion relationships are characterized by homophily in clinical role such that physicians look to physicians as champions, while nurses look to other nurses. Further, prior work has not specifically explored champions in the context of HPV vaccination, though the presence of a champion has been positively associated with HPV vaccination performance in primary care [17]. Thus, we conducted a national survey of adolescent PCPs to evaluate how common vaccine champions are, their roles and attributes, and implementation strategies they use to promote adolescent vaccination, including HPV vaccination. Our findings may guide future efforts to identify, engage, and train champions to deliver evidence-based interventions to support HPV vaccination within clinical settings.

Methods

Participants and procedures

We conducted a web-based survey in May–July 2022 to assess PCPs’ perceptions of and experiences working with vaccine champions in adolescent primary care. Eligible PCPs were physicians, advanced practice providers (i.e., physician assistants and advanced practice nurses), and nursing staff (registered nurses, licensed practical/vocational nurses, medical assistants, and certified nursing assistants). Additionally, eligible respondents (1) were certified to practice in the US; (2) worked in pediatrics or family medicine and general practice (hereafter “family medicine”); and (3) had one or more roles in HPV vaccination for children ages 9–12. Roles in HPV vaccination were specified as assessing children’s vaccination status, notifying parents when children are due for the vaccine, recommending the vaccine, addressing parent questions and concerns, or administering the vaccine.

We contracted with a survey company, WebMD Market Research, to recruit PCPs through the Medscape Network, which provides web-based information, continuing education, and research participation opportunities to the medical community. About 60% of US physicians are members of the network, and Medscape verifies physicians’ and advanced practice providers’ licenses upon registration. In the pre-recruitment phase, the survey company constructed a survey panel by emailing members with the appropriate medical training (i.e., physicians, advanced practice providers, and nursing staff) to assess their interest in survey participation and to filter out inactive members. Members who responded affirmatively were eligible to join the study.

In the recruitment phase, the survey company emailed 6278 panel members a link to the web-based survey, followed by up to four reminders for members who did not respond. We used quotas to ensure balance in our sample by medical training. More specifically, we aimed to include roughly equal proportions of pediatricians, family physicians, advanced practice providers, and nursing staff. Because of rural-urban disparities in HPV vaccination, we oversampled PCPs practicing in clinics located in rural counties, as defined by USDA Rural-Urban Continuum Codes (RUCC) 4-9 [9, 18].

Respondents who clicked the survey link began by completing a 4-item screener that ensured they met eligibility criteria (Supplemental Table 1). A total of 2527 PCPs were eligible, provided informed consent, and completed the survey, yielding a response rate of 57% (Response rate 3, [19]). Respondents in our sample compared favorably to those in the general population on key demographic characteristics (Supplemental Table 2). The median completion time for our survey was 19 min, and respondents received an incentive of up to $45 depending on local market rates for survey research participation. The University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol. We used the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) cross-sectional study guidelines to develop this manuscript [20].

Measures

Our survey began by defining “vaccine champion” with the following statement:

Some health care professionals are known for helping their colleagues improve vaccination rates. They are passionate about sharing vaccine-related information, data, tools, and encouragement with others in their clinic. We will call them vaccine champions.

Respondents next reported how many champions they currently work with, using nine response options that ranged from “0 champions” to “8 or more champions.” This item instructed respondents to “Consider anyone who goes above and beyond to help you or others in your clinic improve vaccination rates. You can count physicians, nursing staff, administrators, quality improvement staff, and others” (Supplemental Table 1). We re-categorized responses as working with any vaccine champion (≥ 1 champion) versus none (0 champions) in order to compare these two groups on their characteristics to understand which PCPs may lack this resource.

For PCPs who worked with any champions, the survey used seven closed-ended items to characterize the champion with whom the respondent worked most closely. One of these items assessed how closely the respondent worked with the champion, using a 5-point response scale to rate the tie as “extremely” to “not at all” close. Another three items used prespecified lists to assess the champion’s medical training, clinical role, and how their role as a vaccine champion is recognized in the clinic. The remaining three items used prespecified lists to assess strategies the champion uses to improve vaccination rates, the kind of vaccination rates they work to improve, and the qualities that best describe them.

We used three survey items to assess champion effectiveness. One of these items assessed perceived effectiveness; respondents used a 5-point response scale to rate their closest champion on effectiveness at improving vaccination rates (“Not at all effective” [1] to “extremely effective” [5]). One closed-ended item assessed respondents’ own HPV vaccine-related behavior in terms of the age at which they begin routinely recommending HPV vaccination for their patients; we recategorized response as 9–10 years, 11–12 years, ≥ 13 years, or never. We used a skip pattern to offer this item only to respondents who indicated having a role in HPV vaccine recommendations. One closed-ended item assessed respondents’ perception of their own clinic’s HPV vaccination rates in terms of whether those rates were at or above their state’s average versus below it. For this item, the survey displayed their state’s HPV vaccination rates for their reference.

Our survey assessed the characteristics of respondents and the clinics in which they worked. Demographic and professional characteristics included PCPs’ gender, race/ethnicity, number of years in practice, and number of patients, ages 9-12, that they see in a typical week. Clinical characteristics included practice type and whether the clinic was part of a healthcare system or network. Two items were collected the county and state of the PCP’s primary clinic, which we used to categorize clinics as rural (RUCC 4–9) or nonrural (RUCC 1-3) [18].

Prior to fielding our survey, we cognitively tested subsets of survey items with 16 PCPs recruited for that purpose, as well as with seven additional PCPs who made up our study’s clinical advisory board. These PCPs included physicians, advance practice providers, nurses, and medical assistants who worked in primary care and were not survey participants. Cognitive interviews used “think aloud” activities to assess whether participants interpreted concepts such as “vaccine champion” as intended by the research team. Their feedback helped the study team to define champions in a way that better distinguished the role of “helping colleagues improve” from more general vaccine promotion with patients and their families. PCPs also provided feedback on the comprehensibility of survey items, including the appropriateness of item wording and response options [21].

Statistical analysis

We used bivariate logistic regression to identify correlates of working with any vaccine champions, modeling the outcome as yes (“≥1 champion”) versus no (“0 champions”). We then entered statistically significant correlates into a multivariable model. We used chi-square tests to assess the association between working with any vaccine champions and each of two effectiveness measures: the age at which respondents delivered routine HPV vaccine recommendations and respondents’ perception of their clinics’ HPV vaccination rates. We conducted analyses using SAS (v 9.4). Statistical tests were two-tailed with a critical alpha of .05.

Results

Participant characteristics

Our sample was comprised of pediatricians (26%), family physicians (22%), advanced practice providers (24%), and nursing staff (28%, Table 1). Over two-thirds of PCPs were women (72%). Most respondents identified as White (66%), Asian (14%), Black (5%), or Hispanic (4%). Our sample included PCPs with a range of practice experience, from low (0–9 years, 37%) to medium (10–19 years, 29%) to high (≥ 20 years, 33%).

Correlates of working with a vaccine champion

Overall, 85% of respondents reported that they currently work with one or more vaccine champions, with 3 champions being the median response for the sample overall. In the multivariable analysis, working with a champion was more common among family physicians, advanced practice providers, and nursing staff compared to pediatricians (81%, 87%, and 90% vs. 80%, p<.05, Table 2). Working with a champion was also more common among PCPs who saw medium and high versus lower volumes of 9- to 12-year-old patients (86% and 90% vs. 78%, p<.05), as well as among those who did versus did not work in a healthcare system (86% vs.82%, p<.05). Working with a champion was less common among PCPs working in the South and the West versus the Northeast (84% and 83% vs. 88%, p<.05). Although PCP female gender correlated with working with a champion in bivariate analyses, this association did not retain statistical significance in the multivariable model.

Champion attributes

PCPs who worked with at least one champion reported on attributes of the champion with whom they worked mostly closely (Table 3). Among these 2,144 PCPs, most reported that they worked very (41%) to extremely (19%) closely with this champion versus moderately closely or less. Champions identified by PCPs most often worked as patient care team members (80%), and about half of PCPs reported that their closest champions’ role was recognized in their job description (38%) and/or job title (19%).

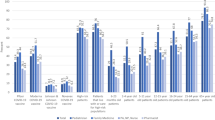

Over one-third of PCPs identified their closest champion as a physician (40%) or nursing staff member (40%), while the remaining one-fifth identified an advance practice provider (17%) or other role (2%, Table 3). With respect to homophily, physician respondents (n=983) identified similar proportions of physicians and non-physicians as their closest champion (49% vs. 49%, Fig. 1). Less than half of nursing staff respondents (n=634) identified another nurse as their closest champion, compared to over half who identified a non-nurse (41% vs. 56%). Only about one-fourth (28%) of advanced practice providers (n=527) identified another advance practice provider as their closest champions, compared to almost three-quarters who identified a physician or nurse (28% vs 71%).

Most PCPs described their closest champion as being knowledgeable about vaccines (91%), trusted by patients and families (84%), an effective communicator (83%), knowledgeable about their clinic (77%), and highly respected by colleagues (74%). Regarding the strategies used to improve vaccination rates, PCPs most often reported that their closest champion communicates effectively with patients and families (85%), shares information with colleagues (79%), encourages colleagues to improve (62%), and shares data on vaccination rates (59%); only a minority of PCPs reported their closest champion leads quality improvement projects (39%). Nearly half of respondents reported that their closest champion works to improve vaccination rates for all vaccines (45%) versus select vaccines such as HPV (49%), seasonal influenza (47%), or COVID-19 vaccines (36%).

Champion effectiveness

Most PCPs perceived their closest vaccine champion to be moderately to extremely effective at improving vaccination rates (91%, Table 3). Furthermore, working with a vaccine champion was associated with HPV vaccine recommendation timing (χ2 = 18.07, p < .001, Fig. 2). More specifically, among the 2294 PCPs who reported recommending HPV vaccine, those who did versus did not work with champions more often reported beginning routine HPV vaccine recommendations at the earliest opportunity of ages 9-10 (44% vs. 33%) and less often reported recommending HPV vaccine later or never. Finally, working with vaccine champions was associated with higher perceived HPV vaccination rates (χ2 = 31.78, p < .001, Fig. 3); PCPs working with champions more often perceived that their clinic’s vaccination rates were at or above their state’s average (68%) compared to those who do not work with a champion (54%).

Discussion

Our study is among the first to detail the roles and characteristics of vaccine champions. Our findings suggest that such champions are common in adolescent primary care, with over four-fifths of PCPs in our national sample reporting that they currently work with one or more champion. Most PCPs characterized the tie to their closest champion as very or extremely close and endorsed that person as having broadly positive qualities. Common champion implementation strategies included encouraging colleagues and sharing information and vaccination data, although only a minority of PCPs reported that champions led quality improvement projects. In this way, champions appear to be a pervasive, but potentially underused resource. Champions may require additional training and support if they are to engage their colleagues in more formal initiatives to improve vaccination rates [6]. Future research should explore barriers and facilitators to champions conducting such work, including champion motivation and willingness, as well as opportunities to support them in selecting the most appropriate implementation strategies for meeting their goals.

In addition to underscoring the importance of vaccine champions for improving vaccination rates in general, our study suggests that champions influence HPV vaccination specifically. PCPs perceived champions as effective in improving vaccination rates and most often identified HPV vaccination as the vaccine on which they focused their efforts as a champion. Furthermore, PCPs who worked with champions reported more positive HPV vaccine recommendation practices and perceptions of their clinic’s HPV vaccination rates. Taken together, these findings suggest that champions may be effective at increasing HPV vaccination, although our study’s cross-sectional design and reliance on self-reported data preclude our ability to establish causality. In prior research, several quasi-experimental and observational studies have identified positive associations between vaccine champions and influenza vaccination, the use of vaccine reminder and recall messages in pediatric and public clinics, and the presence of standing order programs in primary care [22,23,24]. In contrast, several cluster-randomized trials assessing multimodal interventions, including the designation of a champion, found no or modest effects on several vaccines in obstetrics and gynecology clinics, but these studies were not designed to evaluate the impact of champions specifically [25,26,27]. Thus, while vaccine champions are a highly promising implementation strategy, further randomized studies will be needed to provide higher quality evidence of their effectiveness for changing their colleagues’ practices and perceptions and improving HPV vaccination rates.

Towards that end, our findings provide several points of guidance for researchers and quality improvement leaders who seek to engage vaccine champions. First, our finding that champions are highly prevalent suggests that interventionists can expect to consistently find champions in adolescent primary care, although more targeted efforts to identify them may be needed in lower-volume practices that are not part of healthcare systems or that are located in the South or West, where champions were less common. Second, we found that champions came from diverse backgrounds in terms of training, which suggests that interventionists should consider physicians, advanced practice providers, and nurses in the champion role. In fact, given the diversity in PCPs’ relationships to champions, multidisciplinary teams of champions may be the ideal. Such an approach would be consistent with prior studies which have found that engaging multiple champions is preferable to having champions serve alone and could also offer potential relief for over-burdened physicians with limited time for additional duties [2]. Finally, when asked to identify their closest champion, PCPs were equally likely to identify a colleague who was or was not recognized for being a champion in their professional title or formal job description. For this reason, interventionists should consider both institutionally-recognized champions as well as champions who may take on the role more informally, based on their own interest and dedication.

Strengths of this study include data from a large, national sample of PCPs with multidisciplinary representation across physicians, advanced practice providers, and nursing staff in adolescent primary care. Our cross-sectional study design allowed us to collect novel data on champions’ attributes and strategies, but also constitutes a limitation insofar as we cannot establish whether associations, such as that between knowing a champion and positive HPV vaccine recommendations, are causal in nature. Another limitation to our study is the challenge of defining a vaccine champion to PCPs working in adolescent primary care, a field in which support for vaccination services is the norm. We conducted extensive cognitive testing to define vaccine champions as those who help their colleagues improve vaccination rates, as opposed to more general promotion of vaccines to patients and their families. Nevertheless, this concept is vulnerable to misinterpretation, which could lead to overestimation of champion prevalence. Similarly, though we asked PCPs about various champion implementation strategies and whether champions led quality improvement projects, it is possible these champions contribute in various ways or undertake strategies not captured by our survey. Finally, we note that our findings are based on PCPs’ perceptions and self-report. Results describing PCP’s outlook on their performance and the performance of their clinics are subject to biases, including social desirability, but are nonetheless valuable in providing data to inform future intervention research to establish the champions’ impact on vaccination rates.

Conclusion

While the implementation science literature frequently invokes champions, studies directly assessing their role in improving clinical outcomes like vaccination are scarce. Champions are highlighted for their potential to successfully implement clinic-based interventions, but overcoming status quo and other organizational resistance are inherently challenging, and a more detailed understanding of champions will better inform efforts to deliver and sustain health services. To this end, our study finds that vaccine champions are widespread but underutilized in quality improvement projects in adolescent primary care, include PCPs of various training backgrounds, and may or may not have a formal title. The relatively low proportion of champions who participate in quality improvement efforts may indicate the need for training and support for champions to lead more formal initiatives. Future research should explore barriers and facilitators to champions’ work in guiding implementation of health services and promoting adolescent vaccines. Importantly, we find an intriguing association between working with a champion and more positive HPV vaccination behaviors and perceptions, which warrant further evaluation in randomized controlled trials.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available upon request upon study completion.

Abbreviations

- ERIC:

-

Expert recommendations for implementing change

- HPV:

-

Human papillomavirus

- PCP:

-

Primary care professional

- US:

-

United states

References

Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, Damschroder LJ, Smith JL, Matthieu MM, Proctor EK, Kirchner JE. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015;10:21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1.

Miech EJ, Rattray NA, Flanagan ME, Damschroder L, Schmid AA, Damush TM. Inside help: an integrative review of champions in healthcare-related implementation. SAGE Open Med. 2018;6:2050312118773261. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312118773261.

Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. Simon and Schuster; 2010.

Damschroder LJ, Banaszak-Holl J, Kowalski CP, Forman J, Saint S, Krein SL. The role of the champion in infection prevention: results from a multisite qualitative study. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18(6):434–40. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2009.034199.

Santos WJ, Graham ID, Lalonde M, Varin MD, Squires JE. The effectiveness of champions in implementing innovations in health care: a systematic review. Implement Sci Commun. 2022;3:80. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-022-00315-0.

Shea CM. A conceptual model to guide research on the activities and effects of innovation champions. Implement Res Pract. 2021;2:2633489521990443. https://doi.org/10.1177/2633489521990443.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HPV cancers are preventable. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021. Retrieved June 15, 2023, from https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/hcp/protecting-patients.html .

Meites E, Kempe A, Markowitz LE. Use of a 2-dose schedule for human papillomavirus vaccination — updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016. 2016;65(49):1405–8. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6549a5.

Pingali C, Yankey D, Elam-Evans LD, Markowitz LE, Valier MR, Fredua B, Crowe SJ, DeSisto CL, Stokley S, Singleton JA. Vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years—National Immunization Survey-Teen, United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(34):912–9. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7135a1.

St Sauver JL, Rutten LJF, Ebbert JO, Jacobson DJ, McGree ME, Jacobson RM. Younger age at initiation of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination series is associated with higher rates of on-time completion. Prev Med. 2016;89:327–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.02.039.

Gilkey MB, Calo WA, Moss JL, Shah PD, Marciniak MW, Brewer NT. Provider communication and HPV vaccination: the impact of recommendation quality. Vaccine. 2016;34(9):1187–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.01.023.

Gilkey MB, Malo TL, Shah PD, Hall ME, Brewer NT. Quality of physician communication about human papillomavirus vaccine: findings from a national survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev : Publ Am Assoc Cancer Res Cosponsored Am Soc Prev Oncol. 2015;24(11):1673–9. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0326.

Gilkey MB, McRee AL. Provider communication about HPV vaccination: a systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(6):1454–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2015.1129090.

Brewer NT, Hall ME, Malo TL, Gilkey MB, Quinn B, Lathren C. Announcements versus conversations to improve HPV vaccination coverage: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2017;139(1):e20161764. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1764.

Gilkey MB, Heisler-MacKinnon J, Boynton MH, Calo WA, Moss JL, Brewer NT. Impact of brief quality improvement coaching on adolescent HPV vaccination coverage: a pragmatic cluster randomized trial. In: Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention: a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology, EPI-22-0866. Advance online publication; 2022. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-22-0866.

Perkins RB, Legler A, Jansen E, Bernstein J, Pierre-Joseph N, Eun TJ, Biancarelli DL, Schuch TJ, Leschly K, Fenton ATHR, Adams WG, Clark JA, Drainoni ML, Hanchate A. Improving HPV vaccination rates: a stepped-wedge randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2020;146(1):e20192737. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-2737.

Lollier A, Rodriguez EM, Saad-Harfouche FG, Widman CA, Mahoney MC. HPV vaccination: pilot study assessing characteristics of high and low performing primary care offices. Prev Med Rep. 2018;10:157–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.03.002.

US Department of Agriculture. USDA Economic Research Service—Rural-Urban Continuum Codes. USDA Economic Research Service; 2020. Retrieved May 3, 2023, from https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes/ .

American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard definitions: final dispositions of case codes and outcome rates for surveys. 9th ed. AAPOR; 2016.

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, Initiative STROBE. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(4):344–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008.

Terwee CB, Prinsen CAC, Chiarotto A, De Vet HCW, Westerman MJ, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Bouter LM, Mokkink LB. COSMIN standards and criteria for evaluating the content validity of health-related Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: a Delphi study. Qual Life Res in press; 2017.

Albert SM, Nowalk MP, Yonas MA, Zimmerman RK, Ahmed F. Standing orders for influenza and pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccination: correlates identified in a national survey of U.S. Primary care physicians. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13(1):22. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-13-22.

Slaunwhite JM, Smith SM, Fleming MT, Strang R, Lockhart C. Increasing vaccination rates among health care workers using unit “champions” as a motivator. Can J Infect Control: Off J Community Hospital Infect Control Assoc-Can = Revue Can Prev Infect. 2009;24(3):159–64.

Tierney CD, Yusuf H, McMahon SR, Rusinak D, O’Brien MA, Massoudi MS, Lieu TA. Adoption of reminder and recall messages for immunizations by pediatricians and public health clinics. Pediatrics. 2003;112(5):1076–82. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.112.5.1076.

Chamberlain AT, Seib K, Ault KA, Rosenberg ES, Frew PM, Cortés M, Whitney EAS, Berkelman RL, Orenstein WA, Omer SB. Improving influenza and Tdap vaccination during pregnancy: a cluster-randomized trial of a multi-component antenatal vaccine promotion package in late influenza season. Vaccine. 2015;33(30):3571–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.05.048.

Mazzoni SE, Brewer SE, Pyrzanowski JL, Durfee MJ, Dickinson LM, Barnard JG, Dempsey AF, O’Leary ST. Effect of a multi-modal intervention on immunization rates in obstetrics and gynecology clinics. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(5):617.e1-617.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2015.11.018.

O’Leary ST, Pyrzanowski J, Brewer SE, Sevick C, Miriam Dickinson L, Dempsey AF. Effectiveness of a multimodal intervention to increase vaccination in obstetrics/gynecology settings. Vaccine. 2019;37(26):3409–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.05.034.

Acknowledgements

N/A.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P01CA250989. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MG, JHM, and WC conceptualized and designed the study. TQ led data collection and analysis. MB, TQ, and MG wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. SW, CB, WYK, KK, and CS reviewed and provided feedback to the draft manuscript. SW and CB also served as clinical advisory board members who guided and provided feedback on study design and measures. All authors contributed to the interpretation of data, critically reviewed and approved the submitted version of the manuscript, and have agreed to be personally accountable for the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval for this study was provided by the University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Consent for publication

N/A.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplemental Table 1.

Survey items

Additional file 2. Supplementary Table 2.

Characteristics of PCPs in our sample versus those in the Current Population Survey.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Brewington, M.K., Queen, T.L., Heisler-MacKinnon, J. et al. Who are vaccine champions and what implementation strategies do they use to improve adolescent HPV vaccination? Findings from a national survey of primary care professionals. Implement Sci Commun 5, 28 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-024-00557-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-024-00557-0