Abstract

Background

Antenatal clinical practice guidelines recommend routine assessment of weight and provision of advice on recommended weight gain during pregnancy and referral to additional services when appropriate. However, there are barriers to clinicians adopting such best-practice guidelines. Effective, cost-effective, and affordable implementation strategies are needed to ensure the intended benefits of guidelines are realised. This paper describes the protocol for evaluating the efficiency and affordability of implementation strategies compared to the usual practice in public antenatal services.

Method

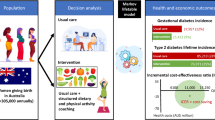

The prospective trial-based economic evaluation will identify, measure, and value key resource and outcome impacts arising from the implementation strategies compared with usual practice. The evaluation will comprise of (i) costing, (ii) cost-consequence analyses, where a scorecard approach will be used to show the costs and benefits given the multiple primary outcomes included in the trial, and (iii) cost-effectiveness analysis, where the primary outcome will be incremental cost per percent increase in participants reporting receipt of antenatal care for gestational weight gain consistent with the guideline recommendations. Affordability will be evaluated using (iv) budget impact assessment and will estimate the financial implications of adoption and diffusion of this implementation strategy from the perspective of relevant fund-holders.

Discussion

Together with the findings from the effectiveness trial, the outcomes of this economic evaluation will inform future healthcare policy, investment allocation, and research regarding the implementation of antenatal care to support healthy gestational weight gain.

Trial registration

Trial Registration: Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry, ACTRN12621000054819 (22/01/2021) http://www.anzctr.org.au/Trial/Registration/TrialReview.aspx?id=380680&isReview=true.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

Gestational weight gain (GWG) above or below recommended levels can lead to poor pregnancy outcomes and potential harm to both mother and child [1]. Such GWG is associated with a higher risk of gestational diabetes [2], preterm and caesarean birth [1], greater postpartum weight retention, and greater risk of obesity long term for the mother [3,4,5], while for the baby, suboptimal GWG is associated higher risk of macrosomia and neonatal morbidity [6]. Poor birth outcomes result in increased healthcare use and morbidity with increased burden on the mother/child, healthcare systems, and society.

To reduce the proportion of women who gain weight outside of recommended ranges, international [7,8,9,10] and Australian national [11] and state [12] antenatal clinical practice guidelines recommended three care elements for addressing GWG in routine antenatal appointments: (a) assessment of GWG using objective measurement of weight against recommended weight gain targets based on pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI), (b) provision of advice for GWG including recommended GWG range, healthy eating, and physical activity recommendations, and consider (c) referral to sources of support (e.g. support services such as Get Health in Pregnancy [13, 14], dietitians, and culturally appropriate referral options to Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services). All patients, regardless of their pre-pregnancy weight, are recommended to receive all three elements of care during their pregnancy at all appointments with antenatal care [11].

However, the provision of such care is suboptimal [15] and constrained by a number of barriers, including lack of time, resources, and skill; and clinician knowledge around GWG procedures and referral sources [15, 16]. Potential implementation strategies to address these barriers and support improvements in the provision of recommended care include education and training, educational resources, and local guidelines and procedures [17,18,19,20]. Controlled trials of such strategies have shown improvements in GWG care, with antenatal care clinicians significantly increasing their provision of assessment and monitoring of weight [21, 22], and advice on healthy weight gain during pregnancy [22,23,24]. However, none of the published studies have reported cost data for, or conducted economic evaluations of, the implementation strategies.

There is a paucity of economic evaluations to assess the cost and cost-effectiveness of implementation strategies in general and for improving antenatal care specifically [25,26,27,28]. Such evaluations are important to conceptualise and evaluate how ‘success’ is defined, along with other implementation outcomes such as practice outcomes, acceptability, and feasibility [29]. Economic evaluations of implementation strategies are required to provide decision makers with comprehensive information regarding economic efficiency, equity, and affordability of strategies to enable translation from research into policy and practice [26].

Several systematic reviews have assessed the quality of economic assessments undertaken as part of implementation trials in the healthcare setting [27, 28, 30] and have found varying levels of quality and fidelity as well as considerable gaps in the assessment of implementation costs. A 2007 review looking specifically at trial-based economic evaluations of implementation strategies found that only six of the 30 studies identified, measured, and valued implementation costs; and if costs were included, the costs were assessed using data that had been collected retrospectively [27]. Another review from 2019 looked more broadly at the evaluation of implementation strategies in healthcare settings and found only 27% of the included studies contained any information on costs [30]. A more recent review from 2021 aimed to assess the extent to which economic evaluations have been applied to antenatal public health interventions. While the included studies costed the components of the strategies, none considered the resource use associated with implementing the interventions into routine practice [28]. The studies included in the 2021 review considered the downstream costs of the consequent behaviour change (e.g. health service use), but none prospectively gathered data for an economic evaluation including strategy implementation costs; the costs needed to fully inform decision makers and funding sources. Furthermore, to date no implementation trials examining strategies to improve GWG care provision have reported economic outcomes.

To address this evidence gap, this paper describes the protocol for an economic evaluation of a package of implementation strategies designed to increase the provision of guideline recommended antenatal care addressing GWG. The described economic evaluation comprises trial-based costing, cost-consequence, cost-effectiveness, and budget impact analysis.

The trial

Study design

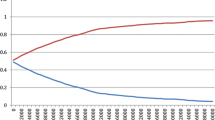

Details of the methods of the primary implementation trial including the CONSORT (stepped-wedge trial) and STARi checklists can be found in the previously published trial protocol [31]. Briefly, a stepped-wedge cluster controlled trial will be conducted in maternity services in three health sectors (clusters) in New South Wales, Australia. The implementation strategies will be delivered sequentially in the three clusters with a 4-month delivery period per cluster (see Fig. 1). All public maternity services providing antenatal care in the three clusters will receive the implementation strategies.

The clusters included in the study are geographically and administratively defined groupings of maternity services with common operational management. The study clusters vary in terms of the size of maternity services (e.g. number of births, number of staff), rural/urban location, and administrative processes (e.g. length of appointment time, mode of delivery for appointments). Being an implementation trial, the study population targeted to receive the implementation strategies are the usual providers of antenatal care in such services, including midwifery group practices, midwifery clinics, specialist medical services, Aboriginal Maternal and Infant Health Services (AMIHS), and multi-disciplinary teams caring for women with complex pregnancies or identified vulnerabilities. Data for the primary outcomes of the trial will be self-reported receipt of GWG care. These data will be collected via telephone/online surveys of pregnant women who received antenatal care at the services in the last 2–3 weeks. Outcomes will be continuously measured from 6 months prior to the intervention in the first cluster until 4 months after the intervention in the third cluster (Fig. 1). The intervention effect will be assessed by comparison of reported receipt of care between the pre- and post-implementation periods for all clusters combined, as described in greater detail in the published trial protocol [31]. It is hypothesised that the implementation strategy, if found to be effective, will also be efficient, affordable, and scalable. This protocol describes the economic evaluation that will address these hypotheses.

Usual practice

Usual antenatal care for addressing GWG (i.e. standard care) will be provided to patients according to existing clinical practice, including any quality improvement strategies being implemented at the local level. Care is likely to vary by maternity service and clinician due to variability in local practice across the three clusters. National clinical practice guidelines [11] were published prior to the trial and hence their associated costs and effects are common to both intervention and control study periods.

Implementation strategies

Multiple evidence-based implementation strategies will be delivered to support maternity service staff in delivering best practice GWG care [11]. The strategies include leadership and management, local clinical practice guidelines, prompts and reminders, local opinion leaders/champions, educational meetings and materials, care delivery monitoring, and feedback (including academic detailing) [31]. The selection and development of the implementation strategies, including behaviour change techniques, were guided by the Behaviour Change Wheel [32] based on a formative assessment of clinician barriers to recommended care delivery using the Theoretical Domains Framework [33]. Previous studies have shown that implementation strategy development based on such frameworks improves guideline and practice adoption [34,35,36]. Further details of the implementation strategies are presented in Table 1.

Methods and analysis

The economic evaluation will be conducted and reported in accordance with the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) publication guidelines and good reporting practices [37]; see additional file for the completed checklist. The evaluation will involve four components: a trial-based costing study, cost-consequence analysis, cost-effectiveness analysis, and budget impact.

Trial-based economic evaluation and budget impact assessment

Identification and measurement of outcomes

The implementation trial aims to improve clinician adherence to the best practice guidelines and will measure three primary outcomes [31]—the proportion of all antenatal clinic appointments (at ‘first appointment’, 27–28 weeks gestation, and 35–36 weeks gestation) for which women report receiving the following:

-

1.

An assessment of GWG using objective measures of weight against recommended weight gain targets

-

2.

Advice on GWG, dietary intake, and physical activity

-

3.

An offer of a referral to the Get Healthy in Pregnancy, a free telephone support service for all women, and when appropriate, offer of a referral to a dietetics service (including culturally appropriate dietetics services for Aboriginal women)

Identification, measurement, and valuation of resource use

Cost data relating to the development and delivery of the implementation strategies will be prospectively collected using a bespoke resource use capture tool in tandem with trial administrative records. The cost capture tool, developed in REDcap [38], allows the research team to document activity and materials related to the strategies that are consumed at different phases (development and execution) and from all relevant stakeholders. The tool records resources aligned to the following categories: (i) labour (health service and non-health service staff, including overheads to allow for additional costs of employment), (ii) materials (non-labour cost items such as stationery, education materials, electronic hardware or software), and (iii) miscellaneous costs (which include costs not easily classified into the other categories, for example, venue hire, travel, and overnight accommodation). Resource use valuation will be based on the concept of opportunity cost, that is, the value of the benefit forgone in not employing a resource for a different use. Where available, market prices will be used as a proxy for the ‘value of benefit’ forgone [39].

Costing study

The trial-based cost analysis will use measures of arithmetic means, between-group differences, and variability of differences [40, 41]. Costs will be aggregated across all clusters, as well as individually for each cluster in the trial. Additionally, component costs will be reported to provide insight into the cost of individual implementation strategies and specific drivers of total cost.

Costs will be reported in 2023 $AUD. A summary of the source of resources and corresponding unit costs is provided in Table 2. The economic evaluation will be performed as a within-trial analysis, indicating that only costs and effects that occur within the trial duration will be included. To maintain a conservative approach to cost estimation, the implementation costs will not be amortised. While the trial period will be 22 months in total, the stepped-wedge design means that any one sector incurs less than 12 months of cost and outcome, hence no discounting is required.

Cost-consequence and cost-effectiveness analyses

The cost-consequence and cost-effectiveness analyses will be undertaken from a public health service perspective. This perspective is relevant as the potential ongoing funding for the implementation strategies when they are translated into usual practice will be from public health services. A budget impact analysis, including scale-up cost scenarios, will also be conducted to further inform decision-makers. Consistent with previous work [42], the cost-consequence analysis will use a scorecard approach to show the comparison of the cost and various outcomes of the implementation strategies and usual practice.

The cost-effectiveness analysis will be conducted subject to evidence of a positive effect of the implementation strategies on practice outcomes. The economic summary measure will be an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) calculated as the incremental cost per proportional difference in participants reporting receipt of ‘antenatal care for GWG consistent with guideline recommendations’ (i.e. a composite of the 3 primary trial outcomes).

Budget impact assessment

While the cost-effectiveness analysis uses opportunity costs, budget impact assessment refers to the calculation of net financial costs resulting from the implementation strategies. In this trial, the elements of the operational cost of the strategies that require a direct financial outlay will be compared to any cash savings to assess affordability over a budget cycle.

Sensitivity and scenario analyses

One-way and probabilistic sensitivity analyses will be conducted to quantify the level of decision uncertainty. In addition, scenario analyses will be undertaken to explore the total cost of implementation at scale across the whole state.

Discussion

The current paper describes the planned economic analysis of implementation strategies to support delivery of guideline recommended care addressing GWG compared to usual practice. This protocol builds on previous methods established by the research team [31, 43, 44] to assess the cost, efficiency, and affordability of implementation strategies to improve the provision of guideline-recommended antenatal care, by improving the data collection tools and further defining the costs. Information on the costs of the implementation of evidence-based interventions is crucial to the adoption of new practices and future scale up. The anticipated results of the trial will add not only to the antenatal care literature, but to the knowledge base for the economic evaluation of implementation strategies.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study will be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AIMHS :

-

Aboriginal Maternal and Infant Health Services

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CHEERS:

-

Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards

- GWG:

-

Gestational weight gain

- ICER:

-

Incremental cost effectiveness ratio

References

Goldstein RF, Abell SK, Ranasinha S, Misso M, Boyle JA, Black MH, et al. Association of gestational weight gain with maternal and infant outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2017;317(21):2207–25.

Bennett CJ, Walker RE, Blumfield ML, Gwini S-M, Ma J, Wang F, et al. Interventions designed to reduce excessive gestational weight gain can reduce the incidence of gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;141:69–79.

Nehring I, Schmoll S, Beyerlein A, Hauner H, von Kries R. Gestational weight gain and long-term postpartum weight retention: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94(5):1225–31.

Mamun A, Mannan M, Doi S. Gestational weight gain in relation to offspring obesity over the life course: a systematic review and bias-adjusted meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2014;15(4):338–47.

Mannan M, Doi SA, Mamun AA. Association between weight gain during pregnancy and postpartum weight retention and obesity: a bias-adjusted meta-analysis. Nutr Rev. 2013;71(6):343–52.

Linder N, Lahat Y, Kogan A, Fridman E, Kouadio F, Melamed N, et al. Macrosomic newborns of non-diabetic mothers: anthropometric measurements and neonatal complications. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2014;99(5):F353–8.

Health Canada. Prenatal Nutrition Guidelines for Health Professionals: gestational weight gain. Canada: Health Canada; 2010.

Public Health Agency of Canada. Your guide to a healthy pregnancy. Ottawa: Canada; 2021.

New Zealand Ministry of Health. New Zealand maternity standards. Wellington, New Zealand: N.Z: Ministry of Health; 2011.

Health Information and Quality Authority. National standards for safer better maternity services. Dublin, Ireland: Health Information and Quality Authority; 2016.

Australian Government, Department of Health. Clinical Practice Guidelines: Pregnancy Care - 2020 Edition. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health; 2020.

New South Wales Ministry of Health. The First 2000 Days Framework. North Sydney: N.S.W: Ministry of Health; 2019.

N.S.W. Government, Department of Health. Get Healthy in Pregnancy Telephone Coaching Service Website: N.S.W. Government; 2021 [05–07–2021]. Available from: https://www.gethealthynsw.com.au/program/get-healthy-in-pregnancy.

Rissel C, Khanal S, Raymond J, Clements V, Leung K, Nicholl M. Piloting a telephone based health coaching program for pregnant women: a mixed methods study. Maternal Child Health J. 2019;23(3):307–15.

Weeks A, Liu R, Ferraro Z, Deonandan R, Adamo K. Inconsistent weight communication among prenatal healthcare providers and patients: a narrative review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2018;73(8):486–99.

Morris J, Nikolopoulos H, Berry T, Jain V, Vallis M, Piccinini-Vallis H, et al. Healthcare providers’ gestational weight gain counselling practises and the influence of knowledge and attitudes: a cross-sectional mixed methods study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(11):e018527.

Freund M, Campbell E, Paul C, et al. Increasing hospital-wide delivery of smoking cessation care for nicotine-dependent in-patients: a multi-strategic intervention trial. Addiction. 2009;104:839–49.

Flodgren G, Parmelli E, Doumit G, Gattellari M, O’Brien MA, Grimshaw J, et al. Local opinion leaders: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;8:Cd000125.

Reeves S, Perrier L, Goldman J, et al. Interprofessional education: effects on professional prac-tice and healthcare outcomes (update). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2013(3):CD002213.

Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, Young JM, Odgaard-Jensen J, French SD, et al. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;6:Cd000259.

Brownfoot FC, Davey MA, Kornman L. Routine weighing to reduce excessive antenatal weight gain: a randomised controlled trial. BJOG: An Int J Obstetr Gynaecol. 2016;123(2):254–61.

Omer AM, Haile D, Shikur B, Macarayan ER, Hagos S. Effectiveness of a nutrition education and counselling training package on antenatal care: a cluster randomized controlled trial in Addis Ababa. Health Pol Plann. 2020;35(Supplement_1):i65–75.

Aguilera M, Sidebottom AC, McCool BR. Examination of routine use of prenatal weight gain charts as a communication tool for providers. Matern Child Health J. 2017;21(10):1927–38.

Malta MB, Carvalhaes MAdBL, Takito MY, Tonete VLP, Barros AJD, Parada CMGdL, et al. Educational intervention regarding diet and physical activity for pregnant women: changes in knowledge and practices among health professionals. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):175.

Hoomans T, Severens JL. Economic evaluation of implementation strategies in health care. Implement Sci. 2014;9(1):168.

Reeves P, Edmunds K, Searles A, Wiggers J. Economic evaluations of public health implementation-interventions: a systematic review and guideline for practice. Public Health. 2019;169:101–13.

Roberts SLE, Healey A, Sevdalis N. Use of health economic evaluation in the implementation and improvement science fields-a systematic literature review. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):72.

Szewczyk Z, Holliday E, Dean B, Collins C, Reeves P. A systematic review of economic evaluations of antenatal nutrition and alcohol interventions and their associated implementation interventions. Nutr Rev. 2021;79(3):261–73.

Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Admin Pol Mental Health. 2011;38(2):65–76.

Vale L, Thomas R, MacLennan G, Grimshaw J. Systematic review of economic evaluations and cost analyses of guideline implementation strategies. Eur J Health Econ. 2007;8(2):111–21.

Kingsland M, Hollis J, Farragher E, Wolfenden L, Campbell K, Pennell C, et al. An implementation intervention to increase the routine provision of antenatal care addressing gestational weight gain: study protocol for a stepped-wedge cluster trial. Implement Sci Commun. 2021;2(1):118.

Michie S, Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6:42.

Michie S, Johnston M, Francis J, Hardeman W, Eccles M. From theory to intervention: mapping theoretically derived behavioural determinants to behaviour change techniques. Appl Psychol. 2008;57(4):660–80.

Grol R, Grimshaw J. From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients’ care. Lancet (London, England). 2003;362(9391):1225–30.

Chaillet N, Dubé E, Dugas M, Audibert F, Tourigny C, Fraser WD, et al. Evidence-based strategies for implementing guidelines in obstetrics: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(5):1234–45.

Baker R, Camosso-Stefinovic J, Gillies C, Shaw EJ, Cheater F, Flottorp S, et al. Tailored interventions to address determinants of practice. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;4:CD005470.

Husereau D, Drummond M, Augustovski F, de Bekker-Grob E, Briggs AH, Carswell C, et al. Consolidated health economic evaluation reporting standards 2022 (CHEERS 2022) statement: updated reporting guidance for health economic evaluations. BMC Med. 2022;20(1):23.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–81.

Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW, O’Brien B, Stoddart GL. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programs. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005.

Ramsey SD, Willke RJ, Glick H, Reed SD, Augustovski F, Jonsson B, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis alongside clinical trials II-An ISPOR good research practices task force report. Value Health. 2015;18(2):161–72.

Henry A, Glick JAD, Seema S, Sonnad Daniel Polsky. Economic evaluation in clinical trials. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2014.

Szewczyk Z, Reeves P, Kingsland M, Doherty E, Elliott E, Wolfenden L, et al. Cost, cost-consequence and cost-effectiveness evaluation of a practice change intervention to increase routine provision of antenatal care addressing maternal alcohol consumption. Implement Sci. 2022;17(1):14.

Reeves P, Szewczyk Z, Kingsland M, Doherty E, Elliott E, Dunlop A, et al. Protocol for an economic evaluation and budget impact assessment of a randomised, stepped-wedge controlled trial for practice change support to increase routine provision of antenatal care for maternal alcohol consumption. Implement. 2020;1(1):91.

Doherty E, Kingsland M, Elliott EJ, Tully B, Wolfenden L, Dunlop A, et al. Practice change intervention to improve antenatal care addressing alcohol consumption during pregnancy: a randomised stepped-wedge controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22(1):345.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This protocol is for a research project funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Partnership Project grant (APP1189756). The NHMRC has not had any role in the design of the study as outlined in this protocol and will not have a role in data collection, analysis of data, interpretation of data, and dissemination of findings. As part of the NHMRC Partnership Grant funding arrangement Hunter New England Local Health District Clinical Services Nursing and Midwifery contributes funds and in-kind support to the project. Individuals in positions that are fully or partly funded by these partner organisations (as described in ‘Competing Interests’ section) will have a role in the study design, data collection, analysis of data, interpretation of data, and dissemination of findings. The University of Newcastle will make final decisions on each of these study aspects.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MK, JH, ZS, PR, OW, and JW led the overall development of the research protocol and OW led the development of the manuscript. EF and JH contributed to the development of the rationale and background for the protocol. JH, MK, JW, and KG contributed to the development of the gestational weight gain pathway and implementation support strategies. BT facilitated the provision of cultural advice and establishment of cultural governance structures. MK, EF, JH, SZ, PR, and OW contributed to the development of data collection methods generally, and ZS, OW, and PR contributed to the development of data collection methods specific to the cost and cost effectiveness measures. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Hunter New England Human Research Ethics Committee (16/11/16/4.07; 16/10/19/5.15), the Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council (1236/16), and the University of Newcastle Human Research Ethics Committee (H-2017–0032; H-2016–0422).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Authors MK, EF, BT, JH, LW, KG, and JW receive salary support from Hunter New England Clinical Services Nursing and Midwifery, which contributes funding to the project outlined in this protocol. JH is a Clinical and Health Service Research Fellow, funded by Hunter New England Local Health District (HNELHD) Partnerships, Innovation and Research through the HNELHD Clinical and Health Service Research Fellowship Scheme. All other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wynne, O., Szewczyk, Z., Hollis, J. et al. Study protocol for an economic evaluation and budget impact of implementation strategies to support routine provision of antenatal care for gestational weight gain: a stepped-wedge cluster trial. Implement Sci Commun 4, 40 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-023-00420-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-023-00420-8