Abstract

Background

This study explores the impact of noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL) on the microstructural integrity of white matter tracts in the brain, focusing on areas involved in speech processing. While the primary impact of hearing loss occurs in the inner ear, these changes can extend to the central auditory pathways and have broader effects on brain function. Our research aimed to uncover the neural mechanisms underlying hearing loss-related deficits in speech perception and cognition among NIHL patients.

Methods

The study included two groups: nine bilateral NIHL patients and nine individuals with normal hearing. Advanced diffusion tensor imaging techniques were employed to assess changes in the white matter tracts. Regions of interest (ROIs), including the auditory cortex, cingulum, arcuate fasciculus, and longitudinal fasciculus, were examined. Fractional anisotropy (FA) values from these ROIs were extracted for analysis.

Results

Our findings indicated significant reductions in FA values in NIHL patients, particularly in the left cingulum, right cingulum, and left inferior longitudinal fasciculus. Notably, no significant changes were observed in the auditory cortex, arcuate fasciculus, superior longitudinal fasciculus, middle longitudinal fasciculus, and right inferior longitudinal fasciculus, suggesting differential impacts of NIHL on various white matter tracts.

Conclusions

The study's findings highlight the importance of considering association fibres related to speech processing in treating NIHL, as the broader neural network beyond primary auditory structures is significantly impacted. This research contributes to understanding the neurological impact of NIHL and underscores the need for comprehensive approaches in addressing this condition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL) is recognized as a significant occupational health issue globally, attributed primarily to excessive exposure to hazardous noise levels. Characterized by the deterioration of hearing sensitivity due to damage to the cochlear hair cells, NIHL not only affects auditory capabilities but also has profound implications on speech perception, cognitive functions, and social interactions [1, 2] The sensory hair cells in the cochlea are essential for converting sound waves into electrical signals that can be interpreted by the brain. When these cells are damaged by excessive noise, it leads to a cascade of changes not just in the cochlea but extending into the central auditory pathways, affecting the brain's ability to process auditory information [1]. This disruption can significantly impair an individual's ability to perceive speech, especially in noisy environments, leading to challenges in social interactions and potentially contributing to feelings of isolation and emotional distress. These associations are believed to arise from the increased cognitive load and compensatory demands placed on individuals with hearing loss as they strive to decode and understand auditory inputs [3, 4]. The exact mechanisms behind this relationship remain an area of active research, highlighting the complexity of hearing loss and its far-reaching implications on brain function.

Hearing loss can have secondary effects on the brain's white matter structure. These structural changes in the white matter may contribute to difficulties in processing auditory information and result in communication challenges for people with hearing loss [5]. Therefore, understanding the neurobiological changes induced by NIHL at a microstructural level is essential. Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), an advanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technique, allows for the visualization and quantification of microstructural white matter tracts in the brain, providing insights into the integrity and organization of these pathways. By measuring the diffusion of water molecules in neural tissues, DTI offers a unique window into the microstructural properties of white matter, including changes in connectivity and integrity that occur in response to sensory deprivation or neural damage [6,7,8]. These changes can affect the transmission of auditory signals and communication between different brain regions involved in auditory processing, ultimately impairing an individual's ability to perceive and understand sound. In the context of NIHL, DTI's capability to assess the fractional anisotropy (FA) values of white matter tracts offers a promising avenue to explore how hearing loss affects the brain's auditory and speech processing networks. FA values, indicative of the directional coherence of water diffusion in tissue, serve as a marker for white matter integrity. Reductions in FA are often interpreted as a sign of decreased white matter organization, potentially reflecting damage or alterations in neural pathways critical for auditory processing and cognitive functions [9, 10].

Understanding white matter changes in NIHL within the auditory cortex and association fibres is essential for gaining insights into the neural basis of hearing loss-related deficits. Investigating white matter changes within this area can help to understand how NIHL affects the neural pathways responsible for perceiving and interpreting auditory information. Our study aims to use DTI to explore the impact of NIHL on the microstructural integrity of white matter tracts involved in speech perception beyond auditory processing. By comparing these findings with a control group of individuals with normal hearing, we aimed to gain insights into the neural mechanisms underlying hearing loss-related deficits in speech perception and cognition among NIHL patients.

Methods

Patients

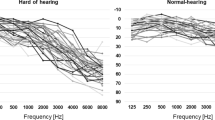

The present work is a cross-sectional study which comprised of two groups: nine bilateral NIHL patients [average age = 45.0 ± 6.1 years] and nine individuals with normal hearing [average age = 38.3 ± 7.8 years). All subjects are gender-matched male patients. The selection of an all-male cohort was driven by the study's focus on occupations traditionally held by males, where noise exposure is more prevalent. For NIHL group, average hearing loss ranged from mild to severe (30 to 90 dB). Our diagnosis of NIHL was based on a combination of individual clinical history, typical audiometric criteria of NIHL (hearing thresholds exceeding 25 dB in 3, 4, and/or 6 kHz combined with a relatively normal threshold at 8 kHz) (Fig. 1), and absence of other otological conditions.

All subjects enrolled in the current study had normal anatomy of auditory circuits in conventional MRI study. The participants had no history of brain surgery, trauma, infection, or ototoxic medication intake. All subjects were submitted to full audiological history and otoscopic examination, and pure tone average data of each subject was obtained. The current study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (IREC 2022-090; 27/07/23), and informed consent was obtained from each subject before the examination.

MRI brain scanning

All MRI scans were conducted using a Siemens 3-Tesla MR scanner. Prior to DTI acquisition, a standard non-contrast MRI was performed to rule out any major abnormalities in the peripheral and central auditory pathways. The MRI protocols comprised the following sequences: (1) T1-weighted imaging: parameters included TE (echo time)/TR (repetition time) of 10/678 ms, a reconstruction matrix of 512 × 512 × 40, a field of view of 230 mm, voxel size of 0.45 × 0.45, slice spacing of 1.0 mm, slice thickness of 2.5 mm, and a flip angle of 70 degrees; (2) T2-weighted imaging: parameters included TE/TR of 80/3000 ms, a reconstruction matrix of 512 × 512 × 24, a field of view of 230 mm, voxel size of 0.45 × 0.45, slice spacing of 1.0 mm, slice thickness of 2.5 mm, and a flip angle of 90 degrees; (3) fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) imaging: parameters included TE/TR/TI (inversion time) of 125/11000/2800 ms, a reconstruction matrix of 512 × 512 × 40, a field of view of 230 mm, voxel size of 0.45 × 0.45, slice spacing of 1.0 mm, slice thickness of 5.0 mm, and a flip angle of 90 degrees.

DTI acquisition

The DTI parameters were adjusted as follows: repetition time of 7649 ms, echo time of 72 ms, flip angle of 90 degrees, field of view of 240 mm, matrix size of 96 × 96, section thickness of 2.5 mm with no gap, one excitation, and an acquisition time of 4 min and 28 s. The diffusion-weighting gradients were applied along 32 noncollinear directions using the electrostatic repulsion model (b0 = 0, 2 image and b1 = 1000 s/mm, 32 images).

DTI data processing

The diffusion imaging data underwent reconstruction using the DTI method with the combined utilization of MRI Converter and DSI Studio software (http://dsi-studio.labsolver.org/). Initially, the Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) data for each participant were imported into MRI Converter to convert the DICOM files (.dcm) into NIfTI file format (.nii), which were subsequently loaded into DSI Studio. Automated registration of the DTI data was performed to correct distortion artefacts. Subsequently, a ".src" file was generated and reconstructed, while ".fib" data were produced to facilitate fibre tracking and tractography, followed by the computation of the mean FA value. The regions of interest (ROIs) evaluated included the auditory cortex, cingulum, arcuate fasciculus (AF), superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF), middle longitudinal fasciculus (MLF), and inferior longitudinal fasciculus (ILF). ROIs from both hemispheres were delineated using a semi-automated method. This approach involved a combination of automated ROI identification, utilizing a validated atlas such as the John Hopkins University (JHU) white matter labels atlas as a template, along with manual interactive selection and modification by the user [11]. Mean FA values were then extracted from the ROIs of both hemispheres for further analysis.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 22.0. Quantitative data were described by calculating the means and standard deviations with p values < 0.05 considered as statistically significant. The independent Student’s t test was used to compare the mean FA value from the selected ROIs between the two groups.

Results

There were no statistical differences between patients and controls for ages. The total 12 white matter tracts from both hemispheres are shown in Fig. 2 (sagittal), Fig. 3 (coronal) and Fig. 4 (axial) section with different colours, including auditory cortex, cingulum, AF, SLF, MLF, and ILF. As shown in Table 1, this study compared FA values between NIHL group and healthy controls, revealing significant differences in several white matter tracts. While the auditory cortex showed no significant differences, the cingulum exhibited significant lower FA values bilaterally in NIHL patients (p value < 0.05). However, no significant differences were found in most of the association fibres such as both sides of AF, SLF, and MLF. Nevertheless, the ILF showed significantly lower FA values in the left hemisphere of NIHL patients (p value < 0.05). These findings suggest that while some white matter tracts may be relatively preserved in NIHL, others associated with cognitive and emotional functions may be more affected.

Discussion

The decrease in FA values in all ROIs in patients with NIHL can be attributed to several underlying neurobiological changes. FA is a DTI metric that measures the degree of directional organization of water diffusion in tissues [12]. Higher FA values typically indicate greater white matter integrity, reflecting more organized and coherent fibre tracts. In comparison, lower FA values suggest reduced directionality of water diffusion, indicative of decreased white matter integrity or altered organization. NIHL can disrupt the efficient transmission of auditory information, potentially leading to decreased FA due to diminished myelination or axonal density in the auditory cortex [9]. Furthermore, altered sensory input with cognitive overload and increased compensatory demands in NIHL may lead to structural changes in the association fibres, reflected in lower FA values in these areas [13].

Our findings showed that the cingulum and left ILF had shown significant alterations in individuals with NIHL compared to healthy subjects. This phenomenon has been highlighted in various neuroimaging studies, demonstrating altered integrity and functional connectivity within these tracts [14, 15]. The cingulum, integral to cognitive and emotional processing, is suspected to be affected due to the stress and cognitive load imposed by hearing loss. Additionally, the disruption in auditory inputs in NIHL could lead to compensatory changes in the cingulum, reflecting its role in multisensory integration [16]. These alterations may account for some of the cognitive deficits observed in NIHL patients, such as difficulties in attention and memory. The ILF connects the occipital cortex to anterior temporal structures and is vital for a wide range of cognitive and affective processes operating on the sensation modality [17]. This multifunctionality and extensive connectivity might make it more susceptible to changes in response to sensory deficits like hearing loss. In most individuals, the left hemisphere is dominant for language processing. Since the ILF is involved in reading and lexical processing, the left ILF might be more actively engaged or affected in hearing loss, especially when it impacts comprehension or communication [17].

However, in our study, the white matter changes did not differ significantly between the two groups in the auditory cortex, AF, SLF, and MLF. This disparity could stem from the inherent resilience or different plasticity mechanisms. The auditory cortex may be more able to adapt to changes in sensory inputs without significant structural alterations [18]. Furthermore, the primary impact of NIHL is on the peripheral auditory system rather than the central auditory pathways, which could explain the lack of significant changes in the auditory cortex [19]. This suggests that while peripheral auditory damage is evident in NIHL, the central auditory system, particularly the auditory cortex, maintains its structural integrity, potentially through adaptive or compensatory mechanisms. Nevertheless, several studies have reported significant structural changes in the auditory cortex of individuals with hearing loss [12, 20, 21]. The varying findings can be attributed to several factors. NIHL is not uniform; it varies greatly in severity and duration among individuals. Some may have mild, short-term exposure to noise, while others might have chronic, severe exposure [2]. This variability can lead to differences in how the auditory cortex is affected. Additionally, the stage of NIHL at which participants are studied can influence findings. Early stages might show different white matter changes compared to more advanced stages [22]. Some studies capture these changes while others may not, depending on when the imaging is done.

Besides the auditory cortex, our study also demonstrated that white matter changes were not observed to differ significantly in the AF, SLF and MLF. These tracts are crucial for language processing and cognitive functions [23]. A study focusing on the diffusion tractography of these tracts illustrated their importance in connecting various brain regions and highlighted the complexity of their functional contributions. The slight resilience of these tracts in NIHL could be due to their role in functions not directly impacted by auditory deficits. For example, while the cingulum is more involved in multisensory integration and emotional processing, the SLF and MLF are primarily associated with language and cognitive functions [24]. Besides, the SLF and MLF have distinct roles compared to the ILF. The SLF is a parieto-frontal tract involved in higher-order cognitive functions. At the same time, the MLF, connecting the superior temporal gyrus with the parietal and occipital lobe, is implicated in language processing and semantic memory [25]. The structural integrity of these tracts might be maintained despite auditory deprivation, suggesting a differential impact of NIHL on various white matter tracts. While the cingulum shows alterations possibly due to its involvement in processing auditory stress and cognitive load, the AF may remain structurally intact due to their distinct functional roles that are less directly affected by auditory input deficits [10, 26]. The specific impact of hearing loss on these tracts may be less pronounced due to their functional specializations. This differential response in white matter tracts could have implications for developing targeted interventions in NIHL, focusing on auditory rehabilitation and cognitive and emotional aspects.

There were some limitations in our study. The main limitation was the small population in both groups, hindering the stratification of patients according to hearing loss severity and healthy individuals. Despite the small sample size, the study provides valuable insights into the neurobiological changes associated with NIHL. The findings contribute to the existing body of literature on the subject and can guide future research and clinical interventions. Furthermore, this exploratory study aimed at investigating the feasibility and potential of using DTI to study white matter changes in NIHL and can be very useful for the viability of future larger-scale studies. Our second limitation of the study is we leveraged standard non-contrast MRI, which, while not optimal for inner ear structure evaluation, suffices for assessing white matter integrity changes. The decision to omit the CISS sequence was influenced by its limited availability in our setting during the study period. We suggest future studies incorporate CISS to enrich the evaluation of peripheral auditory structures in NIHL. In addition, subjects’ ages were not restricted; thus, results may have included age-related brain degeneration. A larger subject pool would be necessary to derive detailed prognosis predictions for different age groups. Besides, we did not measure the long-term effects of NIHL on the brain, and longitudinal studies will be needed to explore changes in brain imaging and NIHL.

Conclusions

Understanding these distinct patterns of white matter changes provides crucial insights into the neurological impact of NIHL. While the primary auditory structures may remain relatively unaltered, the broader neural network, particularly those associated with cognitive and emotional processing, is significantly impacted. This highlights the need for a comprehensive approach to treating NIHL, addressing the auditory deficits and the potential cognitive and psychological consequences.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AF:

-

Arcuate fasciculus

- DICOM:

-

Digital imaging and communications in medicine

- DTI:

-

Diffusion tensor imaging

- FA:

-

Fractional anisotropy

- FLAIR:

-

Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery

- ILF:

-

Inferior longitudinal fasciculus

- MLF:

-

Middle longitudinal fasciculus

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- NIHL:

-

Noise-induced hearing loss

- ROI:

-

Region of interest

- SLF:

-

Superior longitudinal fasciculus

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

References

Chen GD, Fechter LD (2003) The relationship between noise-induced hearing loss and hair cell loss in rats. Hear Res 177(1–2):81–90

Natarajan N, Batts S, Stankovic KM (2023) Noise-Induced Hearing Loss. J. Clin Med 12(6):2347

Wei J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Hao Q, Yang R, Lu H et al (2017) Hearing impairment, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra 7(3):440–452

Ying G, Zhao G, Xu X, Su S, Xie X (2023) Association of age-related hearing loss with cognitive impairment and dementia: an umbrella review. Front Aging Neurosci 15:1241224

Rosemann S, Thiel CM (2020) Neuroanatomical changes associated with age-related hearing loss and listening effort. Brain Struct Funct 225(9):2689–2700

Rigters SC, Cremers LGM, Ikram MA, van der Schroeff MP, de Groot M, Roshchupkin GV et al (2018) White-matter microstructure and hearing acuity in older adults: a population-based cross-sectional DTI study. Neurobiol Aging 61:124–131

Armstrong NM, Williams OA, Landman BA, Deal JA, Lin FR, Resnick SM (2020) Association of poorer hearing with longitudinal change in cerebral white matter microstructure. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 146(11):1035–1042

Chern A, Irace AL, Golub JS (2020) Mapping the brain effects of hearing loss: the matter of white matter. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 146(11):1043–1044

Mudar RA, Husain FT (2016) Neural alterations in acquired age-related hearing loss. Front Psychol 7:828

Luan Y, Wang C, Jiao Y, Tang T, Zhang J, Teng GJ (2019) Prefrontal-temporal pathway mediates the cross-modal and cognitive reorganization in sensorineural hearing loss with or without tinnitus: a multimodal MRI study. Front Neurosci 13:222

de Haan B, Clas P, Juenger H, Wilke M, Karnath HO (2015) Fast semi-automated lesion demarcation in stroke. NeuroImage Clin 9:69–74

Tarabichi O, Kozin ED, Kanumuri VV, Barber S, Ghosh S, Sitek KR et al (2018) Diffusion tensor imaging of central auditory pathways in patients with sensorineural hearing loss: a systematic review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 158(3):432–442

Chen J, Hu B, Qin P, Gao W, Liu C, Zi D et al (2020) Altered brain activity and functional connectivity in unilateral sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Neural Plast 2020:9460364

Zhang Z, Jia X, Guan X, Zhang Y, Lyu Y, Yang J et al (2020) White matter abnormalities of auditory neural pathway in sudden sensorineural hearing loss using diffusion spectrum imaging: different findings from tinnitus. Front Neurosci 14:200

Ponticorvo S, Manara R, Pfeuffer J, Cappiello A, Cuoco S, Pellecchia MT et al (2021) Long-range auditory functional connectivity in hearing loss and rehabilitation. Brain Connect 11(6):483–492

Kraus KS, Canlon B (2012) Neuronal connectivity and interactions between the auditory and limbic systems. Effects of noise and tinnitus. Hear Res 288(1–2):34–46

Zemmoura I, Burkhardt E, Herbet G (2021) The inferior longitudinal fasciculus: anatomy, function and surgical considerations. J Neurosurg Sci 65(6):590–604

Shang Y, Hinkley LB, Cai C, Subramaniam K, Chang YS, Owen JP et al (2018) Functional and structural brain plasticity in adult onset single-sided deafness. Front Hum Neurosci 12:474

Li Q, Guo H, Liu L, Xia S (2019) Changes in the functional connectivity of auditory and language-related brain regions in children with congenital severe sensorineural hearing loss: an fMRI study. J Neurolinguist 51:84–95

Kim SY, Heo H, Kim DH, Kim HJ, Oh SH (2018) Neural plastic changes in the subcortical auditory neural pathway after single-sided deafness in adult mice: a MEMRI study. Biomed Res Int 2018:8624745

Kerkelä L, Nery F, Callaghan R, Zhou F, Gyori NG, Szczepankiewicz F et al (2021) Comparative analysis of signal models for microscopic fractional anisotropy estimation using q-space trajectory encoding. Neuroimage 242:118445

Qu H, Tang H, Pan J, Zhao Y, Wang W (2020) Alteration of cortical and subcortical structures in children with profound sensorineural hearing loss. Front Hum Neurosci 14:565445

Ivanova MV, Isaev DY, Dragoy OV, Akinina YS, Petrushevskiy AG, Fedina ON et al (2016) Diffusion-tensor imaging of major white matter tracts and their role in language processing in aphasia. Cortex 85:165–181

Wang Y, Fernández-Miranda JC, Verstynen T, Pathak S, Schneider W, Yeh FC (2013) Rethinking the role of the middle longitudinal fascicle in language and auditory pathways. Cerebral Cortex (New York, NY:1991) 23(10):2347–2356

Averill Christopher L, Averill Lynnette A, Wrocklage Kristen M, Scott JC, Akiki Teddy J, Schweinsburg B et al (2018) Altered white matter diffusivity of the cingulum angular bundle in posttraumatic stress disorder. Mol Neuropsychiatry 4(2):75–82

Zhang GY, Yang M, Liu B, Huang ZC, Li J, Chen JY et al (2016) Changes of the directional brain networks related with brain plasticity in patients with long-term unilateral sensorineural hearing loss. Neuroscience 313:149–161

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) research grant [03.16/03/NIHL(E)/2023/01]; UMP Grant No: RDU230702.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NA and DA performed subjects’ recruitment. MAMN conducted audiological examination. RSP analysed and interpreted the raw MRI data. MKIZ conducted post processing of DTI analysis and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. MM consulted manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The current study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of International Islamic University Malaysia (IIUM) (IREC 2022-090), and informed consent was obtained from each subject before the examination.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zolkefley, M.K.I., Abdull, N., Shamsuddin Perisamy, R. et al. Investigating white matter changes in auditory cortex and association fibres related to speech processing in noise-induced hearing loss: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Egypt J Radiol Nucl Med 55, 93 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43055-024-01266-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43055-024-01266-3