Abstract

Background

Crohn’s disease is an inflammatory bowel disease which mostly affects the small intestine. It has a variable clinical course, with alternating attacks of exacerbation and remission. In the last decades, the incidence of Crohn’s disease has been increasing, so imaging of those cases has become more important.

Case presentation

We report a case of a male patient who was treated for Chron’s disease in the past three years and presented with abdominal pain. Post-contrast CT abdomen and pelvis was done revealing soft tissue thickening of intestinal walls in a skip fashion with multiple peritoneal deposits. The case was pathologically proven to be anaplastic large cell lymphoma on top of Chron’s disease.

Conclusions

The cause of the association between Crohn's disease and lymphoma is still elucidated. Radiologists should be aware that Chron’s disease can be complicated by intestinal and peritoneal lymphoma and should suspect the presence of lymphoma on top of Chron’s disease if there is wall thickening of soft tissue attenuation affecting the small bowels in a skipping manner following the areas previously affected by Chron’s disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Crohn’s disease is an inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) which mostly affects the small intestine, especially the terminal ilium; however, it can affect any segment of the gastrointestinal tract from mouth to anal canal. It has a variable clinical course, with alternating attacks of exacerbation and remission. In the last decades, the incidence of Crohn’s disease has been increasing, so imaging of those cases has become more important [1].

Case presentation

A 52-year-old male patient with a history of Crohn’s disease for 3 years (proved by endoscopy and biopsy) on treatment, with a recent history of weight loss, night sweating and low-grade fever presented with abdominal pain and enlargement underwent abdominal US that revealed ascites, peritoneal masses and lymph nodes (LNs) referred for CT abdomen and pelvis (Fig. 1).

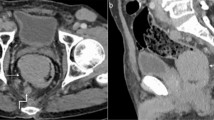

Lymphomatous intestinal affection: Axial (A) and coronal (B) post-contrast CT lower abdomen and pelvis showing marked irregular circumferential mural thickening of multiple segments of small intestinal loops of soft tissue attenuation (red arrows) with short segments of normal wall thickness in between (skipped segments) (green arrows). Pelvic-free fluid is seen (white arrow)

A post-contrast CT abdomen and pelvis was done using multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) enterography using a multidetector-row helical CT scanner (Toshiba Aquilion Prime 160 CT). A discontinuous marked circumferential minimally enhancing soft tissue mural thickening of the ileal loops with loss of identification of the normal three layers of the intestinal walls. The affected segments were separated by normal intestinal segments in between in a skip fashion. There were also multiple peritoneal masses implanted on the hepatic surface extending into the fissures as well as GB fossa with subsequent scalloping of liver surface, implanted on the right kidney surface with subsequent scalloping on its surface and scattered in all pelvi-abdominal regions forming discrete and amalgamated masses (high peritoneal index). Multiple enlarged para-aortic, mesenteric LNs and mild ascites were present (Figs. 2 and 3).

Lymphomatous peritoneal deposits: Axial (A, B) post-contrast CT abdomen showing multiple variable-sized peritoneal deposits indenting hepatic (blue arrows) and right renal (green arrow) surfaces and scatted nodules in left hypochondrial and lumbar regions (yellow arrows). Note normal-sized spleen with normal parenchymal density (white arrow)

Endoscopic guided biopsy from the thickened intestinal walls revealed anaplastic large cell lymphoma on top of Chron’s disease.

Discussion

The cause of the association between Crohn's disease and lymphoma is still elucidated. Some studies reported that the development of lymphoma in Chron’s patients is secondary to the use of immunosuppressive drugs which cause a drop in patient immunity [2].

The imaging characteristic of Crohn’s disease is the skip lesions, meaning there are segments of normal mucosa between the affected segments [3].

Clinically, small bowel lymphoma has nonspecific symptoms like abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and weight loss. The imaging findings of small bowel lymphoma include multifocal polypoid intestinal wall masses, homogeneously enhancing circumferential wall thickening with aneurysmal dilatation as lymphoma lacks desmoplastic reaction, with or without associated mesenteric lymphadenopathy [4].

Lymphoma can also affect the peritoneum giving imaging findings similar to those seen in peritoneal carcinomatosis including omental cakes and diffuse nodular peritoneal thickening [5].

Radiologists should be aware that Chron’s disease can be complicated by intestinal and peritoneal lymphoma and should suspect the presence of lymphoma on top of Chron’s disease if there is soft tissue density with grey enhancement pattern within the thickened bowel wall with loss of normal triple layers of the bowel wall. The most interesting part about our case which according to our knowledge was not reported before is that the wall thickening seen in our case representing lymphomatous infiltration was found in a skipping manner following the areas primarily affected by Chron’s disease (Figs. 2 and 3).

Conclusions

Intestinal lymphoma is one of the complications of Chron’s disease, and when it affects the small bowel loops, it follows the segments primarily affected by Chron’s disease and spares the normal segments in between in a skip manner.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- IBD:

-

Inflammatory bowel disease

- US:

-

Ultrasonography

- LNs:

-

Lymph nodes

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- MDCT:

-

Multidetector computed tomography

- GB:

-

Gall bladder

References

Magalhães FC, Lima EM, Carpentieri-Primo P, Barreto MM, Rodrigues RS, Parente DB (2023) Crohn’s disease: review and standardization of nomenclature. Radiol Bras 56:95–101

Hmidi A, Bel HadjKacem L, Sellami R, Ksentini M, Znaidi N (2023) Primary colonic MALT lymphoma associated with Crohn’s disease: case report and review of the literature. Clinical Case Rep 11(6):e7381

Gaillard F, Ranchod A, Rasuli B, et al. Crohn disease. Reference article, Radiopaedia.org (Accessed on 02 Jun 2023). https://doi.org/10.53347/rID-6791

Lee JS, Park SH, Choi SJ (2023) Radiologic review of small bowel malignancies and their mimicking lesions. J Korean Soc Radiol 84(1):110–126

Cho JH, Kim SS (2020) Peritoneal carcinomatosis and its mimics: a review of CT findings for differential diagnosis. J Belgian Soc Radiol 104(1):8

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study did not receive funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have read and approved the manuscript. Study concept and design were proposed by RK and BE. Database search was performed by RK. Pathological report analysis was carried out by RK. Analysis and interpretation of data and drafting of the manuscript were done by BE. Revision of the manuscript was performed by EO and US. Technical or material support was given by EO and US.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by our institution’s ethics committee (Mansoura Faculty of Medicine Institutional Research Board), A written informed consent was obtained from the patient included in the study.

Consent for publication

The participants in the study were informed and consented to the possibility of research publication. Authors hereby transfer, assign or otherwise convey all copyright ownership to the Egyptian journal of radiology and nuclear imaging if such work is published in that journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Elged, B.A., Karam, R., Khaled, R. et al. Intestinal and peritoneal lymphoma complicating Chron’s disease. Egypt J Radiol Nucl Med 55, 51 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43055-024-01218-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43055-024-01218-x