Abstract

Background

Most anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries which are common in violent sports require anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR) to restore knee joint stabilization. Rectus femoris (RF) and vastus intermedius (VI) weakness are among the notable changes after ACLR. This weakness can be hazardous to the patient as it could decrease functional activity and thus increases the chances of re-injury. The objectives of the current study were to measure the (RF) thickness, (VI) thickness and the total (RF + VI) thickness on (ACL) reconstructed limb and the non-reconstructed limb of athletes using ultrasound and to compare the results pre-operatively and 6–8 months post-operative.

Results

The reconstructed limb showed a significant decrease in (RF), (VI) and the total thickness in the 1st, 2nd and 3rd measurements compared to that of non- reconstructed limb post-operatively. In both limbs, the decrease of (VI) thickness was significantly higher than (RF) thickness in the 1st, 2nd and 3rd measurements (p < 0.001, p < 0.001 and p < 0.001 respectively).

Conclusions

Ultrasound can be used to assess quadriceps atrophy (including the individual muscles) found after ACLR. Ultrasound is an affordable and easily available modality as compared to MRI and CT scans for the assessment of RF and VI muscle weakness in athletes with ACLR during the rehabilitation period and can guide selective rehabilitation protocols if wasting is identified early.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Injuries to the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) are frequent among athletes who play violent sports like American football, basketball, and soccer. Over 60% of knee injuries in sports involving rapid movements are ACL tears. To regain knee joint stabilization following the majority of ACL injuries, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR) is necessary [1].

One of the significant changes following ACLR is the persistence of rectus femoris (RF) and vastus intermedius (VI) weakness after rehabilitation is completed [2]. If this weakness continues, it could be dangerous for the patients since it might change their movement patterns, reduce their functional activity, and raise their risk of re-injury. Additionally, it might reduce patients’ quality of life by delaying their return to regular activities. The full functionality of the RF and VI muscles must be restored in order to best prepare the patient for recovery, but this is frequently not accomplished despite targeted rehabilitation [3, 4].

Further understanding of quadriceps atrophy and strength limits may be possible by recognizing the effects of ACLR on the size and volume of these muscles. In addition, systematic rehabilitation plans can be made based on the size of the quadriceps. Therefore, if muscle loss is detected early after surgery, we can develop structured rehabilitation programs to aid the patient’s recovery [3, 5].

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scans are the best methods currently available for measuring muscle volume and RF and VI thickness, but because of the limited resources, they are neither widely available nor cost-effective for the majority of the population. These techniques are expensive and require specific tools and safety precautions [3, 6].

The aim of this study is to measure the (RF) thickness, (VI) thickness and the total (RF + VI) thickness on (ACL) reconstructed limb and the non-reconstructed limb of athletes using ultrasound and to compare the results pre-operatively and 6–8 months post-operative.

Methods

This prospective study was approved by our Research and Ethics committee (approval code: N-225-2023).

Sixty athletic male patients who were candidates for ACLR surgery were referred to the diagnostic radiology department from the outpatient clinic of the orthopaedic department in the time period from November 2022 to June 2023. All patients presented with ACL tears during playing football were included in our study. Their age ranged from 18 years to 35 years, the mean ± standard deviation age was 26.28 ± 18.2 years and the median was 27 years. Nonathletic patients, patients with bilateral ACL tears, and patients with a history of related operations or internal fixations were excluded from this study.

All cases (n = 60/60) were subjected to B-mode ultrasound (US) pre-operative and 6–8 months post-operative on both reconstructed (RL) and non-reconstructed limbs (NRL) to measure the thickness of rectus femoris, vastus intermedius and the total thickness.

Technique and analysis of the ultrasonographic examination

The Toshiba Ultrasound Aplio 500; Toshiba Medical, Japan machine with the 18 MHz linear probe was used to assess the patients.

With the patient supine and hip external rotation avoided, the thickness of the rectus femoris, vastus intermedius, and total thickness was measured. At the halfway point (50%) between the superior pole of the patella and the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS), the RF and VI thickness were measured. The depth of the image was assessed when the femur was in the centre of the screen after the image had been modified till the muscle boundary was visible on the screen. A single examiner with more than 15 years’ experience in musculoskeletal ultrasound, recorded the ultrasound measurements three times per muscle. The distance between the muscle's superficial and deep borders was used to define the RF thickness. The distance between the superficial border of the muscle and the superficial border of the femur was used to define the VI thickness. The distance between the superficial borders of the RF muscle and the femur was used to define the total thickness.

Statistical analysis

Data were fed to the computer and analyzed using IBM SPSS software package version 25.0 (IBM Corp. Released 2017. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Qualitative data were described using numbers and percentages. The Kolmogorve–Smirnov test was used to verify the normality of distribution. Quantitative data were described using range (minimum and maximum), mean, standard deviation, median and interquartile range (IQR). The significance of the obtained results was judged at the 5% level.

The used tests were

-

1.

Wilcoxon Rank test was used to compare two related samples, matched samples, or to conduct a paired difference test of repeated measurements on a single sample to assess whether their population mean ranks differ.

-

2.

Mann–Whitney test For abnormally distributed quantitative variables, to compare between two studied groups

Sample size calculation

Sample size calculation was carried out using G*Power 3 software [7]. A calculated sample of 52 respondents (26 athletes with ACLR during the rehabilitation period and 26 controls) will be needed to detect an effect size of 0.2 [8] in the mean difference of RF and VI muscles thickness on two repeated measures, with an error probability of 0.05 and 80% power on a two-tailed test.

Results

A total number of 60 patients candidates for ACLR surgery were enrolled in this study. The age of patients ranged from 18 to 35 years, the mean ± standard deviation age was 26.28 ± 18.2 years and the median was 27 years. The left affected limb was reported in more than half of the patients (53.3%).

Post-operative rectus femoris (RF) thickness, vastus intermedius (VI) thickness and the total thickness in the reconstructed limb were significantly smaller compared with their pre-operative thickness in the 1st, 2nd and 3rd measurements (p = 0.001, p = 0.017 and p = 0.001), (p < 0.001, p < 0.001 and p < 0.001), and (p < 0.001, p < 0.001 and p < 0.001) respectively as shown in Tables 1, 2 and 3 and Fig. 1.

A 27-year-old male patient candidate for left ACLR surgery. a ultrasonography showing pre-operative RF (10.6 mm) (arrow) and VI (9.1 mm) (dashed arrow) thickness in the reconstructed limb compared to b post-operative RF (10 mm) (arrow) and VI (8.7 mm) (dashed arrow) thickness. c pre-operative total thickness (18.8 mm) compared to d post-operative total thickness (17.8 mm)

Post-operative rectus femoris (RF) thickness, vastus intermedius (VI) thickness and the total thickness in the non-reconstructed limb were significantly smaller compared with their pre-operative thickness in the 1st, 2nd and 3rd measurements (p = 0.001, p = 0.017 and p = 0.001), (p < 0.001, p < 0.001 and p < 0.001), and (p < 0.001, p < 0.001 and p < 0.001) respectively as shown in Tables 1, 2 and 3 and Fig. 2.

A 29-year-old male patient candidate for left ACLR surgery. a ultrasonography showing pre-operative RF (18 mm) (arrow) and VI (15.2 mm) (dashed arrow) thickness in the non-reconstructed right limb compared to b post-operative RF (14.4 mm) (arrow) and VI (13.7 mm) (dashed arrow) thickness in the non-reconstructed limb. c pre-operative total thickness (33 mm) compared to d post-operative total thickness (27.9 mm) in the non-reconstructed limb

The reconstructed limb showed a significant decrease in rectus femoris (RF) thickness in the 1st, 2nd and 3rd measurements (p < 0.001, p < 0.001 and p < 0.001 respectively) compared to that of non- reconstructed limb post-operatively as shown in Table 1 and Fig. 3.

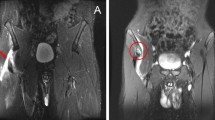

Vastus intermedius (VI) thickness was significantly decreased in the reconstructed limb in the 1st, 2nd and 3rd measurements (p < 0.001, p < 0.001 and p < 0.001 respectively) compared to that of non- reconstructed limb post-operatively as shown in Table 2 and Figs. 4 and 5.

A 20-year-old male patient candidate for right ACLR surgery. a ultrasonography showed decreased VI thickness (11 mm) (dashed arrow) in the reconstructed limb postoperatively compared to b pre-operative VI thickness (15.6 mm) (dashed arrow). c Post-operative decreased VI thickness (13.7 mm) (dashed arrow) compared to d pre-operative VI thickness (15.2 mm) in the non-reconstructed limb

Post-operatively the total thickness was significantly decreased in the reconstructed limb in the 1st, 2nd and 3rd measurements (p < 0.001, p < 0.001 and p < 0.001 respectively) compared to that of the non-reconstructed limb as shown in Table 3 and Fig. 6.

In both limbs, the decrease of vastus intermedius (VI) thickness was significantly higher than rectus femoris in the 1st, 2nd and 3rd measurements (p < 0.001, p < 0.001 and p < 0.001 respectively) post-operatively as shown in Tables 4 and 5.

Discussion

The Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) is the most commonly injured.

Quadriceps muscle weakness (including the individual muscles) is a result of cruciate ligament rupture and may persist after reconstruction [7]. Most patients undergo rehabilitation programs, however, they report deficits in knee function that may affect their ability to resume sports. Finding modifiable causes of the decline in self-reported functional levels is crucial for maximizing rehabilitation following ACLR [2].

Imaging‐based measures of quadriceps size (including the individual muscles) help to illustrate the role of quadriceps atrophy as an underlying factor that contributes to quadriceps weakness and functional deficits following ACL injury [5]. Quantifying the quadriceps muscle size (including the individual muscles) in people with ACLR is frequently done using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT). However, they are not easily accessible and come at a high cost [9, 10].

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to set an affordable and easily available modality for the assessment of RF and VI muscles’ weakness in athletes with ACLR during the rehabilitation period.

Ultrasound was used to examine sixty athletic male patients candidates for ACLR surgery injured during playing football.

Post-operative rectus femoris (RF), vastus intermedius (VI) and total thickness in the reconstructed limb were significantly smaller compared with their pre-operative thickness in the 1st, 2nd and 3rd measurements. This was supported by the study conducted by Yang JH et al. [1] who studied the effects of ACLR on individual quadriceps muscle thickness using ultrasound and found a significant reduction in the total thickness, RF and VI thickness post-operatively.

In the current study, post-operative vastus intermedius (VI) thickness in the reconstructed and non-reconstructed limbs was significantly smaller compared with their pre-operative thickness in the 1st, 2nd and 3rd measurements. The post-reconstruction VI thickness (16.04, 6.13 mm) on RCL was significantly lower than the pre-reconstruction VI thickness (19.89, 6.91 mm, p = 0.001), according to the study by Joo et al. [11], the post-reconstruction VI thickness (20.90, 5.78 mm) on the healthy limb (HL) was also significantly lower than the pre-reconstruction VI thickness (22.88, 6.07 mm, p = 0.019).

Joo et al. [11] aimed to compare the thickness of the rectus femoris muscle in both operated and non-operated limbs, there were significant differences between both lower limbs. This prospective study showed the same results in which the reconstructed limb had a significant decrease in rectus femoris (RF) thickness in the 1st, 2nd and 3rd measurements compared to that of the non-reconstructed limb.

In this study, vastus intermedius (VI) thickness was significantly decreased in the reconstructed limb in the 1st, 2nd and 3rd measurements (p < 0.001, p < 0.001 and p < 0.001 respectively) compared to that of the non-reconstructed limb, this was matching with several previous studies reported that VI thickness in the RCL was smaller than that in the healthy limb (HL) after ACLR, the primary difference was the muscle thickness assessment time period after surgery [11].

There was no effect on the RF muscle thickness (there was only a significant time effect on RF thickness), according to Joo et al. [11], investigating the quadriceps' response to ACLR in a short period of time (48–72 h). This finding was consistent with our long-term study (6–8 months), which found that the decrease in vastus intermedius (VI) thickness was significantly higher than that of the rectus femoris in the 1st, 2nd and 3rd measurements (p < 0.001, p < 0.001 and p < 0.001 respectively).

Limitation of the study

There are some limitations in this study; the specific surgical method and process, such as a selection of graft type and specific surgical techniques, were not controlled. Therefore, there was a possibility of surgical influence on quadriceps atrophy. The sample size is not large enough for a powerful conclusion. Another limiting factor was investigating the patients by a single examiner. Furthermore, the rehabilitation of the subjects after surgery was not controlled. The frequency and intensity of rehabilitation can potentially affect the thickness of each muscle in the quadriceps.

Conclusions

Ultrasound can be used to assess quadriceps atrophy (including the individual muscles) found after ACLR. Ultrasound is an affordable and easily available modality as compared to MRI and CT scans for the assessment of RF and VI muscle weakness in athletes with ACLR during the rehabilitation period and can guide selective rehabilitation protocols if wasting is identified early.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ACL:

-

Anterior cruciate ligament

- ACLR:

-

Anterior cruciate ligament reconstructive surgery

- ASIS:

-

Anterior superior iliac spine

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- EI:

-

Echo intensity

- HL:

-

Healthy limb

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- NRL:

-

Non-reconstructed limb

- MHz:

-

Mega hertz

- MML:

-

Millimeter

- MR:

-

Magnetic resonance

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- P value:

-

Probability value

- RF:

-

Rectus femoris

- RL:

-

Reconstructed limb

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- US:

-

Ultrasound

- VI:

-

Vastus intermedius

- 2D:

-

Two dimensional

References

Jae HY, Seung PE, Dong HP, Hyo BK, Eunwook C (2019) The effects of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction on individual quadriceps muscle thickness and circulating biomarkers. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16(24):48–95

Steven AG, Mike NV, Skylar CH, Melissa MM, Derek NP (2020) Quadriceps muscle size, quality, and strength and self-reported function in individuals with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Athl Train 55(3):246–254

Shubham A, Hemant J, Kishore R, Jagdish G, Sunil C (2021) Early quadriceps wasting after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in young adults: a prospective study. J Clin Diagn Res 15(4):8–11

Birchmeier T, Lisee C, Kane K, Brazier B, Triplett A, Kuenze C (2020) Quadriceps muscle size following ACL injury and reconstruction: a systematic review. J Orthop Res 38(3):598–608

Rangio GA, Chen C, Kalady M, Reed J (1997) Thigh muscle size and strength after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and rehabilitation. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 26(5):238–243

Lisee C, Lepley AS, Birchmeier T, O’Hagan K, Kuenze C (2019) Quadriceps strength and volitional activation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Health 11(2):163–179

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A (2007) G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioural, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 39:175–191

Buelga-Suarez J, Alba-Martin P, Cuenca-Zaldívar N, García-Escudero M, Bierge-Sanclemente P, Almazán-Polo J, Fernández-Carnero S, Pecos-Martín D (2022) Test-retest reliability of ultrasonographic measurements from the rectus femoris muscle 1–5 years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in the ipsilateral and contralateral legs: an observational, case-control study. J Clin Med 11(7):18–67

Mota JA, Stock MS (2017) Rectus femoris echo intensity correlates with muscle strength, but not endurance, in younger and older men. Ultrasound Med Biol 43(8):1651–1657

Saxena S, Sarkar A, Naik AK (2021) Comparison of quadriceps muscle girth using ultrasound imaging in supervised vs unsupervised postoperative ACL reconstruction. MLU 20(4):592–597

Joo HL, Soul C, Hyung PJ, Yu-LH EC (2020) Bilateral comparisons of quadriceps thickness after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Medicina 56(7):335

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our special thanks and gratitude to our staff members who gave us the chance to do this research. We really appreciate the patients included in this study.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NK analyzed and interpreted the patient data regarding the ultrasonographic results of the post-operative data of both limbs. AH analyzed and interpreted the patient data regarding the pre-operative ultrasonographic findings of both limbs. AA examined the patients, decided the patient’s candidates for ACLRS and performed the operations. ME revised all the data interpreted by other authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The current study had been approved by Kasr El-Aini Hospital, Research and Ethical Committee (approval Code: N-225-2023).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

The authors affirm that human research participants provided informed consent for the publication of the images in the figures.

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kandil, N.M., El Toukhy, M.M., Al-Feeshawy, A.S.H. et al. Rectus femoris and vastus intermedius thickness measurement by ultrasound before and after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in athletes. Egypt J Radiol Nucl Med 54, 152 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43055-023-01106-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43055-023-01106-w