Abstract

Background

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) has well-described imaging findings, typically reversible with the adequate treatment. We hereby report a case of IIH with a peculiar imaging finding, that to our knowledge and by the research conducted, has never been described before—cerebro-spinal fluid (CSF) transudation across the optic nerve sheath.

Case presentation

A 15-year-old girl with a 2-week history of occipital headache, nausea and vomiting, diplopia, blurred vision and tinnitus in her right ear, was admitted in the neuropediatric department and after extensive diagnostic work-up was diagnosed with IIH. The MRI showed typical signs of idiopathic intracranial hypertension, including enlargement of the perioptic CSF spaces associated with a peculiar finding described as a blurred hyperintensity T2/FLAIR of the perioptic fat, which was likely related to transudation of CSF. The adequate medical therapy (including corticosteroids and acetazolamide) for 2 weeks didn’t revert the signs and symptoms and so a lumboperitoneal shunt was placed with complete resolution of the clinical picture and the imaging findings described.

Conclusions

The documentation of CSF transudation around the optic nerve in the setting of hydrops has never been reported before and should be recognized by the neuroradiologist. It seems to be reversible, like the other findings of IIH and its physiopathology is not clear.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The optic nerve is a white matter tract of the central nervous system that passes through the optic canal into the orbit, enveloped by the perioptic meninges, which are continuous with the intracranial meninges [1,2,3]. For this reason, pressure changes in the intracranial space can be transmitted to the optic papilla via the subarachnoid space (SAS).

Intracranial hypertension occurs in a spectrum of neurological disorders where cerebro-spinal fluid (CSF) pressure within the skull is elevated. Normal CSF pressure varies by age. In general, CSF pressure above 250 mmH20 in adults and above 280 mmH20 in children signifies increased intracranial pressure [4, 5]. This finding may be idiopathic or arise from a neurologic insult or injury.

The idiopathic form is a neurological disorder characterized by elevated intracranial pressure in the absence of any known causative factor (mass lesions, inflammation, cerebral venous thrombosis), of unclear etiology, that most often occurs in obese women of childbearing age [4, 6].

Most commonly the patient presents with headache, vision changes, tinnitus and diplopia [4, 6].

Neuroimaging is the first step in the evaluation of a patient with increased intracranial pressure, since most structural causes of increased intracranial pressure can be identified. Several findings on neuroimaging suggest increased intracranial pressure, including dilation and increased tortuosity of the optic nerve sheaths, flattening of the posterior sclera, and occasionally, the optic discs may appear swollen and enhance after contrast. Additional neuroimaging signs include an empty sella turcica, acquired cerebellar tonsillar descent below the level of the foramen magnum and smoothly tapered stenoses in the transverse venous sinuses [4].

Treatment of dural ectasia of the optic nerve sheath depends on optic nerve functions. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, such as acetazolamide, may be beneficial in some cases [4]. In cases with persistent papilledema, surgical decompression of the optic nerve sheath and CSF shunting should be considered in the treatment [4, 7].

We report one imaging feature from our patient with idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) that, to our knowledge, is not reported in the literature: the transudation of CSF across the optic nerve sheath to the orbit’s perioptic fat, shown on MR by a blurred hyperintensity T2/FLAIR.

Case presentation

A 15-year-old female patient presented to the emergency department with a 2-week history of occipital headache and cervical pain, that was later accompanied with nausea, vomiting, diplopia, blurred vision and tinnitus in her right ear. She denied fever, cough or other significant symptoms.

At physical examination, the patient was uncomfortable with a grimace of pain, showed some neck stiffness, and presented a bilateral incomplete third and sixth nerve palsy with reduction of visual acuity in both eyes. Fundoscopy examination showed bilateral papilledema with retinal hemorrhages. The remaining neurologic examination was normal and body mass index was normal for age.

Routine laboratory investigations such as complete hemogram, c-reactive protein, renal and hepatic functions were within normal limits. Angiotensin-converting enzyme was also normal.

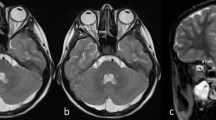

Neuroimaging showed signs of raised intracranial pressure in the absence of a parenchymal or extra-axial lesions, with dilation of perioptic CSF spaces, flattening of the posterior sclera and swelling of the optic discs, small pituitary gland for the age group with superior concavity and the peculiar finding of blurred hyperintensity T2/FLAIR of the perioptic orbital fat, that was correlated to likely transudation of CSF around the optic nerve sheath (Fig. 1).

A 15-year-old female with a 2-week history of occipital headache and cervical pain, later accompanied with nausea, vomiting, diplopia, blurred vision and tinnitus in her right ear. MR, sagittal T1WI a revealed a small pituitary gland for the age group with superior concavity (arrow), presumably secondary to the raised intracranial pressure. Axial FLAIR (b) and axial T2WI c showed flattening of the posterior contour of the eye globes with apparent protrusion/swelling of the optic discs (asterisks). In coronal T2WI d an enlargement of the optic nerve/sheath complex (arrows) was denoted and confirmed by the coronal T2WI FatSat e, f in which the enlargement was conspicuous in more than one slice and surrounded by a high signal of the perineural fat related to transudation of CSF (arrows)

Lumbar puncture was performed demonstrating an opening pressure > 500 mmH2O, with normal CSF cytochemical characteristics.

An extensive infectious panel was performed, with negative results.

After multidisciplinary discussion, idiopathic intracranial hypertension was assumed as the probable diagnosis.

Pharmacological treatment with antibiotics (Ampicillin, Ciprofloxacin and Ceftriaxone), Acetazolamide (maximum of 1500 mg/day) and Metilprednisolone (30 mg/kg) over 2 weeks was ineffective.

Considering the clinical features and failed best medical treatment, a lumboperitoneal shunt was placed with significant clinical improvement presenting no ocular or neurologic signs at the time of the discharge.

A follow-up MRI was performed showing major resolution of the optic nerves’ hydrops without signs of transudation or papilledema, with reconstitution of the pituitary gland size (Fig. 2).

MR of the same patient after external lumbar shunt placement, revealed in sagittal T1WI a a normal size pituitary gland with superior convexity (arrow), as expected to the age group; apparent completely resolution of the posterior eye globes flattening (asterisks) on axial T2WI (b) and return to normal size of the optic nerve/sheath complex without signs of transudation on the coronal T2WI FatSat (arrows) (c)

Clinical long-term follow-up, after 3 years, revealed no sequelae with the patient remaining asymptomatic.

Discussion

We describe a rare case of perioptic CSF transudation, as an indirect sign of intracranial hypertension.

Nerve sheath hydrops can occur unilaterally or bilaterally and may be due to mechanical/extrinsic obstruction conditioned by neoplastic or benign lesions. Frequently bilateral dilatation of the optic nerve sheath is associated with IIH since pressure changes in the intracranial space can be transmitted to the perioptic subarachnoid space [2,3,4,5,6,7].

The perioptic subarachnoid space differs from other SAS owing to its trabeculated structure, with a blind end behind the globe—“cul-de-sac” anatomy. It is anatomically divided into bulbar, intra-orbital, and canalicular segments. These divisions are not uniform in architecture: The bulbar segment consists of trabeculae, the intraorbital segment septa and pillars, and the canalicular portion trabeculae and pillars, a meshwork that undoubtedly plays an important role in maintaining the pressure within the nerve [1].

The CSF movement, in the optic nerve, begins at the basal cistern and through its intracranial portion and via the optic canal reaches the intraorbital segments to the lamina cribrosa at the posterior contour of the globe [6].

Previous studies have shown impaired CSF dynamics in perioptic SAS within the orbital optic nerve segments in patients with IIH, with findings suggestive of “compartmentalization” and limited CSF circulation in this space, with consequent accumulation of potential neurotoxic substances, findings that together (mechanical and biochemical) may lead to neuronal, axonal and glial cell damage [6].

Although it is somewhat possible to explain this finding of perioptic CSF transudation, it was the first case observed in our department and, as far as we can ascertain, not reported in the literature. We question whether the timing of clinical evolution and neuroimaging would have any influence, as well as the severity of the opening pressure, but due to the frequency of the pathology we would say that this is a rare finding indeed. The reversibility of this finding was proved in the follow-up MRI although the mechanism behind it remains unclear and needing further investigation. Different etiologies, other than raised ICP, could be implicated in the meningeal barrier dysfunction with CSF transudation such as infections, trauma, vascular and neurodegenerative diseases but not applicable in the present case.

The presence of CSF transudation across the optic nerve sheath in a patient with IIH is a useful diagnostic tool as it provides evidence of increased intracranial pressure ICP, which is a key characteristic of IIH. The transudation of CSF into the optic nerve sheath can be seen on imaging studies such as MRI or ultrasound and can help confirm the diagnosis of IIH when combined with other clinical and imaging findings.

In the management of IIH, the finding of CSF transudation across the optic nerve sheath can also be used to monitor the effectiveness of treatment interventions aimed at reducing ICP. For example, if treatment is successful in lowering ICP, the transudation of CSF across the optic nerve sheath would expectably decrease or resolve on subsequent imaging studies, as shown in this case. This can provide objective evidence of the success of treatment and help guide further management decisions.

Conclusions

Optic nerve sheath dilation is frequently present in the setting of HII, but a leakage (transudation) of the CSF across the meningeal casing has not been reported before but, as shown in this case, might happen in this context. The resolution of the described finding after adequate treatment suggests its reversibility, even though its exact physiopathologic mechanism is not clearly known and requires further investigation.

In summary, the finding of CSF transudation across the optic nerve sheath can help in the diagnosis and management of idiopathic intracranial hypertension by providing evidence of increased ICP and by monitoring the effectiveness of treatment interventions aimed at reducing ICP.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CSF:

-

Cerebro-spinal fluid

- IIH:

-

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension

- SAS:

-

Subarachnoid space

References

Killer HE, Laeng HR, Flammer J et al (2003) Architecture of arachnoid trabeculae, pillars, and septa in the subarachnoid space of the human optic nerve: anatomy and clinical considerations. Br J Ophthalmol 87:777–781. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.87.6.777

Passi N, Degnan AJ, Levy LM (2013) MR imaging of papilledema and visual pathways: effects of increased intracranial pressure and pathophysiologic mechanisms. Am J Neuroradiol 34:919–924. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A3022

Sheng J, Li Q, Liu T et al (2022) Cerebrospinal fluid dynamics along the optic nerve. Front Neurol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2022.931523

Thurtell MJ (2019) Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Contin Lifelong Learn Neurol 25:1289–1309. https://doi.org/10.1212/CON.0000000000000770

Avery RA, Shah SS, Licht DJ et al (2010) Reference range for cerebrospinal fluid opening pressure in children. N Engl J Med 363(9):891–893. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc1004957

Pircher A, Montali M, Pircher J et al (2018) Perioptic cerebrospinal fluid dynamics in idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Front Neurol 9:1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2018.00506

Hutzelmann A, Buhl R, Freund M (1998) Pseudotumour cerebri and optic hydrops—magnetic resonance imaging diagnostic and therapeutical considerations in a paediatric case. Eur J Radiol 28:126–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0720-048X(97)00149-6

Acknowledgements

Not Applicable

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by DK, GGL and TPM. The first draft of the manuscript was written by DK and all authors reviewed and commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kuroedov, D.S., Lobo, G.G., Morais, T.P. et al. Perioptic cerebro-spinal fluid transudation: case report of an unusual finding of optic hydrops in idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Egypt J Radiol Nucl Med 54, 40 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43055-023-00992-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43055-023-00992-4