Abstract

Background

Tubercular infection of the brain and spine is relatively common in endemic regions of the world. Central nervous system tuberculosis can have varied manifestations. The familiar imaging findings are hydrocephalus, ring-enhancing tuberculomas, and meningeal enhancement, having a preference for basal regions. Myelitis is the most common imaging manifestation of spine, with holocord involvement being a rare presentation, as seen in our case.

Case presentation

We present a case of a pediatric patient undergoing treatment for a tubercular infection of the brain. The patient developed acute onset quadriparesis, manifesting as holocord transverse myelitis on imaging. The imaging findings in the brain manifested as basal meningeal enhancement and non-communicating hydrocephalus, managed by shunt placement. As of the latest, the patient is on follow-up and has a stable disease course. Clinical and laboratory investigations excluded other infectious and non-infectious causes of transverse myelitis, including neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders.

Conclusions

Longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis is a rare complication of tubercular myelitis seen as a long-segment signal abnormality with swelling of the cord and corresponding post-contrast enhancement. Involvement of the entire cord is rare, with a handful of cases reported in the literature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Tuberculosis (TB) is the leading cause of death in the adult population attributable to a single infectious agent worldwide. It presents a challenging public health problem, especially in developing countries like India, with one of the highest endemicity [1]. Central nervous system (CNS) affection is seen in approximately 1% of these cases, with spinal cord involvement even more unique [2]. The commonly encountered manifestations of Central nervous system tuberculosis (CNS-TB) include tuberculous meningitis (95%), parenchymal tuberculoma, cerebritis, frank abscess formation, and radiculomyelitis. Other infrequent manifestations include calvarial tuberculosis, spinal arachnoiditis, and spinal cord infarction [3]. Intramedullary spinal tuberculosis is uncommon and manifests as tuberculomas, radiculomyelitis, and rarely as transverse myelitis.

Longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis (LETM) is exceedingly rare, with only a few isolated cases reported [4]. Longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis is characterized by immune-mediated inflammation of the spinal cord extending for three or more segments producing marked neurological deficits [5]. This article highlights this under-recognized entity with no documented prevalence. Prompt and accurate diagnosis is imperative since it is potentially treatable and prevents adverse outcomes.

Case presentation

We present a case of a 4-year-old child diagnosed with tubercular meningitis in October 2021 based on clinical evaluation and laboratory tests, including cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis. Antitubercular therapy was initiated promptly with corticosteroids and pyridoxine support. A ventriculoperitoneal shunt was placed to manage hydrocephalus. The compliance with medication was satisfactory, and the patient was on outpatient follow-up.

Six months later, the patient presented to the emergency with recurrent low-grade fever and acute onset quadriparesis. At the time of presentation, the patient was conscious, had a mild fever, generalized hypotonia with a power of 0/5, and complete sensorimotor loss, including bladder and bowel control.

There were no clinical signs of cerebellar or cranial nerve involvement. No recent history of vaccination was present. The patient was admitted and further worked up.

Apart from raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate rest of the findings were unremarkable. The fever and autoimmune profile were negative, including oligoclonal bands and antibodies to aquaporin-4. Nerve Conduction Study demonstrated decreased compound muscle action potentials in the major upper and lower limb nerve distribution with average F wave latencies bilaterally.

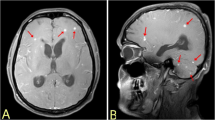

Contrast Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging (CE-MRI) of the brain revealed communicating hydrocephalus with enhancing exudates in the peripontine cistern and on the surface of the cerebellum (Fig. 1).

Contrast Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the spine in the same sitting revealed intramedullary T1 hypointense and T2 hyperintense signal abnormality involving more than two-thirds cross-section area of the cord. There were corresponding areas of cord enhancement manifesting as patchy enhancement in cord substance and surface enhancement of the entire cord, extending beyond conus medullaris as enhancement and clumping of cauda equina nerve roots (Figs. 2 and 3). Central canal exudates and syrinx were seen in the upper cord, with prominent thecal sac space enhancing septae in the lumbosacral region as ancillary features (Fig. 4). Based on the imaging findings, diagnosis of longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis was proposed with brain imaging conforming to pre-existing tubercular etiology.

The patient was treated with intravenous steroids and immunoglobulins, with a modified antitubercular regime. After five days, the patient showed significant improvement, with a return of the power of 2/5 in all four limbs. After one month, the patient was discharged once regular feeding was re-established. The patient was advised to revisit on an outpatient basis and to promptly contact the treating physician or present to the emergency department in case of any sudden deterioration in limb function/consciousness or adverse effect of medications.

Discussion

Imaging intracranial and spinal tuberculosis features are nonspecific and often challenging, making diagnosing tuberculous myelitis difficult even in TB-endemic regions. The term ‘tuberculous radiculomyelitis’ (TBRM), coined by Dastur and Wadia [6], includes spinal cord complications of TB myelitis, such as arachnoiditis or spinal granulomas. They described the findings as a comparison between operative findings and histopathology. The changes were seen as dense exudates with thick septae adherent to the spinal cord. Areas of cord hemorrhage with associated arterial thrombosis were also seen. Tuberculomas were seen as well-defined circular structures. The histopathological manifestation was the presence of tuberculomas with surrounding reactive giant cells, lymphocytes, and plasma cells, as well as exudates containing microcysts. The earliest description of spinal tuberculosis was given in 1988 by Rhoton et al. [7].

Fever, weight loss, and generalized weakness commonly present constitutional symptoms [8]. Pain or tenderness in the spine is usually not present [9]. CNS involvement can manifest as altered sensorium or vomiting, with associated hydrocephalus being a partial contributor for latter [9]. Depending on the segment cord involved, upper and lower limbs mixed motor and sensory involvement manifest as mono, para, quadriplegia, or paresis. Similar segmental involvement was seen in the case of radiculopathy [10]. Bladder and bowel involvement usually occurs late in the disease [8, 9].

CSF examination findings may include high protein, lymphocytic pleocytosis, and culture infrequently favorable for acid-fast bacilli [8,9,10].

The commonly encountered imaging manifestation in a series of 15 cases included cord expansion, T1 hypointense, and T2 hyperintense intramedullary signal abnormality with or without heterogeneous or ring enhancement pattern attributable to the presence of a necrotic component in the latter [8,9,10]. Similar T1 and T2 signal changes showing no appreciable enhancement with relatively well-defined margins are attributed to changes in syrinx [10]. The thoracic cord is the most frequently affected segment.

Another review citing ten cases of TB myelitis confirmed similar T1 and T2 signal abnormalities, with cervical and thoracic cord segments frequently involved. In addition, cord expansion and enhancement features were also seen, consistent with our case. There may be cases showing T2 hypointense signal abnormality, explained by caseous necrosis as opposed to T2 hyperintensity of edema. A study also proposed cavitation as a marker for a worse prognosis, with another study stating incomplete recovery in cases of syrinx formation [9].

Tuberculous radiculomyelitis manifests as thick inflammatory exudates within subarachnoid space and granuloma formation in or on the surface of the spinal cord. This granuloma eventually ruptures into subarachnoid space and incites an exudative inflammatory response. With time, the tenacious exudates organize themselves to produce adhesions between dura and cord, indistinct cord outline, and formation of CSF loculations [11]. Adhesive Arachnoiditis manifests on imaging as an empty thecal sac sign with a T2 hyperintense signal of CSF occupying a large cross-section area of thecal sac due to clumping of nerve roots centrally or peripherally with or without associated tethering [10]. Abnormal postcontrast enhancement of nerve roots is almost always seen, as in our case. Obliterative endarteritis eventually leads to ischemia, myelomalacia, and syrinx formation of long cord segments [12]. The same cord changes are also observed in our case, portraying the chronic nature of the ailment. The decrease in the postcontrast enhancement of spinal meninges post-treatment indicates treatment response [11]. There can be associated changes of vertebral changes in the form of altered marrow signal, discal or paradiscal abscess formation, vertebral collapse, or paraspinal collections.

A case report of LETM encountered in the past emphasized poor penetration of antitubercular medication into CSF post-subsidence of the inflammatory response [13]. In our case, the probable mechanism of LETM was an immune-mediated inflammatory response to degraded tubercular proteins exacerbated by antitubercular drugs [14]. Another possibility can be a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to tubercular proteins [15].

Our patient developed LETM despite good adherence to antitubercular treatment. It may be related to the paradoxical response of antitubercular therapy, characterized by clinical worsening or the appearance of new lesions on imaging following a period of initial significant clinical response [16]. Interestingly, despite this pseudoprogression, Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging (DCE-MRI) trans (permeability) and ve (leakage) values representing blood–brain barrier (BBB) dynamics confirmed therapeutic response to medication [15, 16].

Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) is the most common cause of LETM, although less specific for the pediatric age group, seen as the second most common manifestation after optic neuritis. LETM can be coexistent with tuberculosis, with myelin essential protein being postulated common antigen as tubercular exposed lymphocytes showed a propensity to affect myelin [15]. Studies have shown clinical improvement after administering antitubercular treatment in NMOSD cases, establishing an association between the two [17, 18]. NMOSD lesional morphology corresponds to T2 high signal/bright spotty lesions, corresponding T1 low signal abnormality, and characteristic lenticular enhancing morphology on the sagittal plane. The cervical cord central gray matter is the site of predilection with invariable involvement of area postrema [19, 20]. The involvement of the dorsolumbar cord was a rare occurrence, as stated in one study [21]. One of the critical considerations when diagnosing NMOSD is the timing of acquiring a scan, as brain lesions are often forerunners of spinal abnormality, and a follow-up scan invariably reveals new onset spinal lesions [20, 21].

Although, in our case, the diagnosis of LETM was based on combined clinical, laboratory, and imaging inputs, it is sometimes difficult to reach a unifying diagnosis. A broad differential category must be considered, such as infective, inflammatory disorders, demyelinating disease, autoimmune and paraneoplastic etiology. The mainstay of treatment is antitubercular therapy and corticosteroids to combat inflammatory response and supportive care.

Conclusions

Tubercular infection of the central nervous system commonly involves the brain, with spinal cord involvement secondary affliction. Myelitis involving the entire cord is a rare manifestation of cord involvement, with a handful of cases reported in the literature. The present case emphasizes prompt diagnosis and early treatment to avoid catastrophic sequelae like LETM. Henceforth whenever a case of central nervous system tuberculosis is encountered, a high index of suspicion is to be reserved for cord involvement to prevent associated morbidity.

Availability of data and materials

No.

Abbreviations

- CNS-TB:

-

Central nervous system tuberculosis

- LETM:

-

Longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- CE-MRI:

-

Contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging

- TBRM:

-

Tuberculous radiculomyelitis

- DCE-MRI:

-

Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging

- NMOSD:

-

Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder

References

Tuberculosis (2022) World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis. 12 Sept 2022

Rock RB, Olin M, Baker CA, Molitor TW, Peterson PK (2008) Central nervous system tuberculosis: pathogenesis and clinical aspects. Clin Microbiol Rev 21(2):243–261

Al-Deeb SM, Yaqub BA, Sharif HS, Motaery KR (1992) Neurotuberculosis: a review. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 94:30–33

Moghtaderi A, Alavi Naini R (2003) Tuberculous radiculomyelitis: review and presentation of five patients. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 7(12):1186–1190

West TW (2013) Transverse myelitis-a review of the presentation, diagnosis, and initial management. Discov Med 16(88):167–177

Dastur D, Wadia NH (1969) Spinal meningitides with radiculo-myelopathy. 2 pathology and pathogenesis. J Neurol Sci 8:261–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-510x(69)90113-0

Rhoton EL, Ballinger WE Jr, Quisling R, Sypert GW (1988) Intramedullary spinal tuberculoma. Neurosurgery 22(4):733–736. https://doi.org/10.1227/00006123-198804000-00019

Ramdurg SR, Gupta DK, Suri A, Sharma BS, Mahapatra AK (2009) Spinal intramedullary tuberculosis: a series of 15 cases. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 111(2):115–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2008.09.029

Wasay M, Arif H, Khealani B, Ahsan H (2006) Neuroimaging of tuberculous myelitis: analysis of ten cases and review of literature. J Neuroimaging 16(3):197–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-6569.2006.00032.x

Gupta R, Garg RK, Jain A, Malhotra HS, Verma R, Sharma PK (2015) Spinal cord and spinal nerve root involvement (myeloradiculopathy) in tuberculous meningitis. Medicine 94(3):404. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000000404

Trivedi R, Saksena S, Gupta RK (2009) Magnetic resonance imaging in central nervous system tuberculosis. Indian J Radiol Imaging 19(4):256–265. https://doi.org/10.4103/0971-3026.57205

Sharma A, Goyal M, Mishra NK, Gupta V, Gaikwad SB (1997) MR imaging of tubercular spinal arachnoiditis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 168(3):807–812. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.168.3.9057539

Gamage R, Senaviratne U, Constantine G (2015) Paradoxical progression of intracranial tuberculous lesions during treatment. Ceylon Med J 45(1):31. https://doi.org/10.4038/cmj.v45i1.7953

Jain RS, Kumar S, Tejwani S (2015) A rare association of tuberculous longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis (LETM) with brain tuberculoma. Springerplus 4(4):476. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-015-1232-z

Zhang Y, Zhu M, Wang L, Shi M, Deng H (2018) Longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis with pulmonary tuberculosis: two case reports. Medicine 97(3):e9676. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000009676

Haris M, Gupta RK, Husain M et al (2008) Assessment of therapeutic response on serial dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI. Clin Radiol 63(5):562–574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crad.2007.11.002

Silber MH, Willcox PA, Bowen RM et al (1990) Neuromyelitis optica (Devic’s syndrome) and pulmonary tuberculosis. Neurology 40:934–938. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.40.6.934

Feng YQ, Guo N, Huang F et al (2010) Anti-tuberculosis treatment for Devic’s neuromyelitis optica. J Clin Neurosci 17:1372–1377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2010.02.023

Dutra BG, da Rocha AJ, Nunes RH, Júnior MACM (2018) Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders: spectrum of MR imaging findings and their differential diagnosis. Radiographics 38(1):169–193. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.2018170141

Kim HJ, Paul F, Lana-Peixoto MA et al (2015) MRI characteristics of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder: an international update. Neurology 84(11):1165–1173. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000001367

Pekcevik Y, Mitchell CH, Mealy MA et al (2016) Differentiating neuromyelitis optica from other causes of longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis on spinal magnetic resonance imaging. Mult Scler 22(3):302–311. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458515591069

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concepts: SR, RD, MDK. Design: SR, RD. Definition of intellectual content: SR, RD, MDK. Literature search: SR, RD, MDK. Data acquisition: SR, RD, MDK. Manuscript preparation: SR, RD, MDK. Manuscript editing: SR, RD. Manuscript review: SR, RD, MDK. Guarantor: RD. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Yes, written consent was taken to undertake the MRI scan.

Consent for publication

Yes, verbal consent was taken.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ranjan, S., Dev, R. & Keisham, M.D. A sporadic case of holocord tuberculous transverse myelitis with arachnoiditis. Egypt J Radiol Nucl Med 53, 252 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43055-022-00937-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43055-022-00937-3