Abstract

Background

Aggressive angiomyxoma is an infrequent benign tumor that usually occurs in the pelvic region. Pelvic masses have variety of differential diagnosis but some featured findings should prompt the diagnosis of aggressive angiomyxoma by the radiologist.

Case presentation

A 40-year-old female patient presented with a two-year history of perineal swelling. Radiological examination including gray scale and color Doppler ultrasound, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was consistent with the diagnosis of aggressive angiomyxoma. The patient underwent surgical operation that ensures total resection of the tumor.

Conclusion

In the case of extensive pelvic soft tissue mass with characteristic imaging findings, the radiologists should take the diagnosis of aggressive angiomyxoma into consideration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Aggressive angiomyxoma is a rarely encountered benign mesenchymal tumor that occurs predominantly in the pelvic and perineal area, with a strong female predominance in premenopausal age group [1]. Approximately 350 cases have been reported in the literature and due to its rarity, prevalence in the population is unknown [2, 3]. Despite its name, it represents a benign tumoral lesion and the term “aggressive” emphasizes the often infiltrative nature of the tumor and its frequent association with local recurrence [2, 4]. Imaging in terms of the extent of the lesion is of paramount importance because of the type of the surgical management that could eliminate the probability of recurrence [5]. The huge pelvic component of an aggressive angiomyxoma deep in relation to the pelvic diaphragm is not appreciated on clinical examination and can frequently be mistaken for Bartholin cyst, lipoma, rectocele or perineal hernia until radiologic evaluation [6]. Herein, the radiologic landmarks including sonographic, tomographic, magnetic resonance imaging features as well as the surgical and pathological specimen images of an aggressive angiomyxoma case are presented to familiarize radiologists and clinicians with the distinctive imaging characteristics.

Case presentation

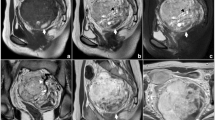

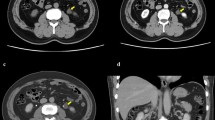

A 40-year-old female patient presented with a two-year history of perineal and right gluteal swelling with mild distension in the lower abdomen. Urinary symptoms including urgency and frequent urination were also expressed by the patient. Past surgical history revealed the patient had been operated 16 months earlier for the same lesion, misdiagnosed as a rectocele. Physical examination findings were so convincing for rectocele that the surgeon did not need radiological imaging prior to surgery. The small amount of soft tissue removed during the transvaginal surgery was not sent to pathology by virtue of the thought that it was fatty tissue causing the rectocele. Due to the persistence of symptoms despite the surgical intervention, she was admitted to the hospital for further investigation. The general surgeon directed the patient to the radiology department for a comprehensive ultrasonographic evaluation with the pre-diagnosis of pelvic lipoma, recurrent rectocele and ovarian malignancies due to the pelvic fullness. An abdominal ultrasound (Toshiba Aplio 500 ultrasound system (Otawara, Japan)) showed an enormous hypoechoic mass extending from umbilical level caudally to perineal region (Fig. 1). The mass was measured to be approximately 40 × 20 × 14 cm in size, displaced the uterus, left ovary and the bladder anteriorly and the rectum left posteriolaterally, with poor intralesional vascularization revealed by color Doppler ultrasound. Right ovary could not be evaluated through transabdominal sonographic examination and no pathologic lymph node was noted. A tomographic study was planned in order to narrow pre-diagnoses. Contrast enhanced computed tomography (128 slice GE Optima CT660 CT scanner (USA)) of the patient revealed the well-defined mass occupied a large intraabdominal volume located between L2 vertebra level and perineal region, causing anterior displacement of bladder and uterus. The lesion caused rectal compression resulting in left lateral displacement of rectum. There was internal swirling enhancing tissue (Fig. 2). Contrast enhanced MRI (1.5 Tesla system (Magnetom Avanto; Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany)) showed 42 × 22 × 15 cm enhancing tissue that has isointense signal intensity with the skeletal muscle on T1 weighted images. A laminated pattern with alternating hyper- and hypointense linear areas due to the presence of collagen fibrils in the myxoid tissue were seen on T2 weighted images (Fig. 3). Swirling or laminated pattern on contrast-enhanced MRI was characteristic for the aggressive angiomyxoma and it provided the diagnosis. An extensive surgery with the intent of achieving clear surgical margins was planned to minimize the risk of tumor residual disease given the propensity for tumor recurrence. A large retroperitoneal pinkish-red lesion with a membranous envelope was excised during surgery (Fig. 4). She had no complication during or after surgery and she was discharged at sixth day postoperatively. Thick walled vessels and collagen fibers in a myxoid stroma were seen on pathologic examination (Fig. 5). Immunohistochemical evaluation was positive for desmin, CD34, estrogen and progesteron receptors in stromal cells. Labelling for Ki-67 demonstrated a low proliferative index (1% of tumor cells). The follow up of the patient with 6 month intervals revealed no symptom or recurrence for 2 years.

a Axial contrast enhanced computed tomography images shows subtle swirled enhancing tissue internally (arrow). b Sagittal tomographic image reveals the extent of the lesion that starts from L2 vertebra level and goes down below the pelvic floor. c Axial image showing left lateral displacement of rectum (arrow) and anterior displacement of uterus due to the compressive feature of the lesion (double arrows). d Coronal oblique tomographic view shows the lesion extending below the pelvic floor

a, b Sagittal and coronal T2 weighted image indicates laminated pattern resulting from collagen fibrils (arrows). c T1 weighted axial image without contrast shows left lateral rectal displacement (arrow) and anterior uterine displacement (double arrows). d Axial contrast enhanced T1 weighted image shows intense enhancement pattern

Discussion

Aggressive angiomyxoma of the female pelvis is quite a rare benign neoplasm that was first described in 1983 and has been occasionally reported since then [1, 7]. The tumor is derived from mesenchymal tissue mostly from the pelvic and perineal regions including the genitourinary tract and rectum [8,9,10]. However, relatively uncommon localizations such as lung, liver, larynx, and orbit have been described as sporadic case reports [10,11,12]. It is not possible to estimate the exact incidence of aggressive angiomyxoma among the other intra-abdominal mesenchymal tumors given its rarity [13]. Patients present with symptoms like urinary frequency and pelvic fullness along with soft tissue herniation from the pelvic floor, largely due to space-occupying feature of the lesion and external compression. Aggressive angiomyxomas display unusual growth patterns like translevator extension with displacement of perineal structures rather than invasion with preservation of fat planes between the tumor and the organs in the vicinity [4, 14]. Although the name implies malignant features, the lesion itself is a benign tumor that can recur if complete resection is not achieved. That is why the tumor is named as aggressive, highlighting high risk of relapse. Wide surgical excision is the mainstay of therapy [15]. Confident preoperative diagnosis is important to ensure wide excision and minimize the recurrence risk [16]. Misdiagnosis of the lesion can lead to inappropriate treatment that may expose the clinician to malpractice litigation. Familiarity with radiologic findings has a significant impact on the preoperative diagnosis process especially for radiologists. On sonographic imaging, aggressive angiomyxoma typically appears as a hypoechoic soft tissue mass, which may appear cystic [17]. CT imaging demonstrates a mass with sharp borders with lower density from the musculature [18]. MR appearances are characteristic and typically demonstrate an isointense tumor relative to muscle on T1-weighted and hyperintense on T2-weighted imaging [19]. A useful distinguishing imaging feature on T2-weighted MRI is presence of laminated appearance attributed to collagen fibrils in a background of loose myxoid stroma [20]. In the literature search in aggressive angiomyxoma cases; case review published by Surabhi et al. [20] presented that the most common site was pelvic and perineal region and there was characteristic laminated appearance on MRI. These features were also observed in our case which make the case consistent with the literature.

Conclusions

In summary, the presence of an extensive pelvic soft tissue mass with internal laminated appearance should alert the radiologist to a possible diagnosis of aggressive angiomyxoma. The constellation of imaging characteristics, such as hypoechoic sonographic appearance, hypodensity on CT, laminated T2-weighted imaging features should prompt the diagnosis of a pelvic aggressive angiomyxoma.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

References

Steeper TA, Rosai J (1983) Aggressive angiomyxoma of the female pelvis and perineum. Report of nine cases of a distinctive type of gynecologic soft-tissue neoplasm. Am J Surg Pathol 7:463–475

Sutton BJ, Laudadio J (2012) Aggressive angiomyxoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med 136(2):217–221

Wang YF, Qian HL, Jin HM (2016) Local recurrent vaginal aggressive angiomyxoma misdiagnosed as cellular angiomyofibroblastoma: a case report. Exp Ther Med 11(5):1893–1895

Outwater EK, Marchetto BE, Wagner BJ, Siegelman ES (1999) Aggressive angiomyxoma: findings on CT and MR imaging. Am J Roentgenol 172:435–438

Narang S, Kohli S, Kumar V, Chandoke R (2014) Aggressive angiomyxoma with perineal herniation. J Clin Imaging Sci 4:23

Fetsch JF, Laskin WB, Lefkowitz M, Kindblom LG, Meis-Kindblom JM (1996) Aggressive angiomyxoma: a clinicopathologic study of 29 female patients. Cancer 78:79–90

Srinivasan S, Krishnan V, Ali SZ, Chidambaranathan N (2014) “Swirl sign” of aggressive angiomyxoma—A lesser known diagnostic sign. Clin Imaging. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinimag.2014.04.001

Nakamura T, Miura K, Maruo Y, Sunayama K, Maruyama K, Kashiwabara H, Ohata K, Fukazawa A, Nakamura S (2002) Aggressive angiomyxoma of the perineum originating from the rectal wall. J Gastroenterol 37(4):303–308

Salman MC, Kuzey GM, Dogan NU, Yuce K (2009) Aggressive angiomyxoma of vulva recurring 8 years after initial diagnosis. Arch Gynecol Obstet 280(3):485–487

Izadi F, Azizi MR, Ghanbari H, Kadivar M, Pousti B (2009) Angiomyxoma of the larynx: case report of a rare tumor. Ear Nose Throat J 88(7):E11

Qi S, Li B, Peng J, Wang P, Li W, Chen Y, Cui X, Liu C, Li F (2015) Aggressive angiomyxoma of the liver: a case report. Int J Clin Exp Med 8(9):15862–15865

Geng J, Cao B, Wang L (2012) Aggressive angiomyxoma: an unusual presentation. Korean J Radiol 13(1):90–93

Sozutek A, Irkorucu O, Reyhan E, Yener K, Besen AA, Erdogan KE, Gonlusen G, Doran F (2016) A giant aggressive angiomyxoma of the pelvis misdiagnosed as incarcerated femoral hernia: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Surg. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/9256749 (PMID: 27274880)

Catalano O (1998) Case report: aggressive angiomyxoma of the pelvic soft tissue: US and CT finding. Clin Radiol 53:782–783

Haldar K, Martinek IE, Kehoe S (2010) Aggressive angiomyxoma: a case series and literature review. Eur J Surg Oncol 36:335–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2009.11.006

Kim HM, Pyo JE, Cho NH, Kim NK, Kim MJ (2008) MR imaging of aggressive angiomyxoma of the female pelvis: case report. JKSMRM 12:206–210

Yaghoobian J, Zinn D, Ramanathan K, Pinck RL (1987) Hilfer J (1987) Ultrasound and computed tomographic findings in aggressive angiomyxoma of the uterine cervix. J Ultrasound Med 6:209–212

Lee KA, Seo JW, Yoon NR, Lee JW, Kim BG, Bae DS (2014) Aggressive angiomyxoma of the vulva: a case report. Obstet Gynecol Sci 57:164–167

Jeyadevan NN, Sohaib SA, Thomas JM, Jeyarajah A, Shepherd JH, Fisher C (2003) Imaging features of aggressive angiomyxoma. Clin Radiol 58:157–162

Surabhi VR, Garg N, Frumovitz M, Bhosale P, Prasad SR, Meis JM (2014) Aggressive angiomyxomas: a comprehensive imaging review with clinical and histopathologic correlation. Am J Roentgenol 202:1171–1178

Acknowledgements

No acknowledgments.

Funding

This study was not supported by any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MC: Software, writing- original draft preparation. AK: Data curation, writing- original draft preparation. AA: Visualization, investigation. IT: Supervision. DOA: Software, validation. EC: Conceptualization, methodology, reviewing and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

For this type of study formal consent is not required. Informed Consent was given by the patient.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication was obtained for every individual person’s data included in the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cingoz, M., Kilic, A., Acar, A. et al. Radiologic imaging findings of pelvic aggressive angiomyxoma correlated with surgical and pathological features. Egypt J Radiol Nucl Med 52, 259 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43055-021-00642-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43055-021-00642-7