Abstract

Background

Cerebral or brain hemorrhage due to the rupture of intracranial aneurysms is extremely rare in pediatric population. The aim of our work is to describe two cases in children and to review the existent bibliography about this issue.

Case presentation

Both of our patients presented with nonspecific symptoms and subsequent neurological deficit. The brain imaging test revealed intraparenchymal hemorrhage. In both cases, the aneurysm was located at the distal portion of the middle cerebral artery. Surgical intervention was needed, clipping the aneurysm due to the impossibility of intravascular embolization. After the surgery, one patient presented with persistent hydrocephalus secondary to intraventricular hemorrhage, requiring the placement of a cerebrospinal fluid shunt. Over time, the child presented with refractory epilepsy compatible with West syndrome. The second patient did not present postoperative complications but died suddenly 2 months after.

Conclusions

Our two patients presented with a middle cerebral artery aneurysm at the distal level, which seems to be the most frequent location according to literature. The correct diagnosis can be delayed because of the nonspecific initial symptoms, as occurred in one of our patients with a delay of 3 days from the onset of symptoms. In both patients, surgical treatment was preferred over endovascular treatment, due to the anatomical characteristics of the aneurysm and the patient’s age.

Torpid evolution is also described, with one of our patients dying at 2 months, probably due to rebleeding, and the other suffering right hemiparesis and epilepsy compatible with West syndrome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The rupture of intracranial aneurysms is extremely rare in pediatric population, but when it occurs, subarachnoid hemorrhage is the most common presentation [1,2,3]. The symptoms can vary according to the location of the brain hemorrhage. Seizures are frequent consequence [4]. Endovascular embolization and surgical clipping are two valid therapeutic options [5]. Our aim with this work is to describe the cases of two pediatric patients admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit of a tertiary hospital with the diagnosis of spontaneous intraparenchymal cerebral hemorrhage. Secondarily, we aim to review the existent bibliography about this pathology.

Case presentation 1

The first patient is a 2-month-old female; as background, they reported that in the previous 20 days, he had been vomiting intermittently; in addition, they had noticed that he lateralized his eyes from time to time. They consulted the emergency room for somnolence with intermittent irritability of several hours of evolution, refusal of feeding, and vomiting. Feverish in the emergency room, she also presented with a decreased level of consciousness, a decreased mobility with muscle hypertonia of right limbs, a right central facial hemiparesis, and a left tonic conjugate gaze deviation. Her parents reported a decreased mobility of the right hand of several weeks of evolution. A transfontanellar ultrasound and a brain computed tomography (CT) were performed, observing an insular and left temporal intraparenchymal hemorrhage, opened to the left lateral ventricle with dilation of the ventricles, and an associated subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) and mass effect with a peri-lesional edema component. At the time of diagnosis, the diameters of the hematoma were 5.4 × 3.4 × 4 cm. No underlying lesion was identified. Hemostasis was unaltered in the blood test performed. Because of the clinical and radiological findings, the patient was admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit (ICU).

During the first hours, she presented with a generalized convulsion, successfully treated with midazolam. Posteriorly, treatment with levetirazetam (LV) 20 mg/kg/day was started. Within the next hours, the patient presented with symptoms of intracranial hypertension (ICHT), with a tendency to hypertension and bradycardia. Posteriorly, she presented with new episodes of gaze deviation that required infusion of midazolam and an increase of the dose of LV to 40 mg/kg/day. Also, at the time of the admission, dexamethasone 0.6 mg/kg/day was started, which was maintained for 10 days. Besides, because of the presumptive diagnosis of SAH, a preventive treatment for vasospasm was started with oral nimodipine 5 mg/4 h, which was maintained for 21 days.

The main suspected diagnosis was arteriovenous malformation or a ruptured aneurysm. A brain magnetic resonance (MR) was performed then (Fig. 1), failing to distinguish the lesion, so an angiography was performed (Fig. 2) finally showing a distal aneurysm of the left middle cerebral artery (MCA) of 4 × 3 cm.

Brain MR of case 1. A, B, and C Transverse planes. D Coronal plane. Large subacute frontal and left temporal hematoma measuring 6 × 4 × 3.5 cm, open to the ventricular system and subarachnoid space. Dilatation of the lateral ventricles with asymmetry due to the mass effect of the hematoma on the left system

Surgical intervention was needed, performing an external clipping of the aneurysm due to the impossibility of intravascular embolization, which was successful. The procedure consists of performing a craniectomy, locating the vessel affected by the aneurysm and placing a small metal clip at its base, thus allowing the bleeding to stop and the vessel wall to heal. Although being technically simple, this surgery can be dangerous due to the sensitive structures around. During the intervention, brain parenchyma showed signs of hypertension, so an external ventricular drain was placed. Postoperative angiography showed the resolution of the aneurysmatic bleeding, with preserved distal flow, and posterior imaging tests (CT and transfontanellar ultrasound) did not show active bleeding or areas of ischemia.

After the surgery, she presented with complications related to the external ventricular drainage, with episodes of cerebrospinal fluid leak around the catheter, which finally required a catheter replacement. In addition, she developed fever, so empirical antibiotic treatment was started after the extraction of blood and cerebrospinal fluid cultures, all of them being sterile. Due to the persistent need for ventricular bypass, a permanent system (ventriculoperitoneal shunt) was finally placed. The patient showed progressive improvement of neurological symptoms, with no more seizures, and so musculoskeletal rehabilitation was started.

At discharge, right facial paresis resolved, with normalization of the level of consciousness, adequate suckling present, improvement of the right hemiparesis, and disappearance of the tendency to gaze to the left.

In the following months, epileptic seizures reappeared, with partial characteristics (arm spasms) and with torpid evolution even with correct preventive treatment. The symptoms and the electroencephalogram were compatible with West syndrome. A deterioration of neurological development was also noted in controls.

Case presentation 2

A 5-week-old female, with no relevant previous history, whose mother consulted for her refusal to feed, vomiting, and pale skin. Her parents reported a previous history of stools with mucus, without other pathological products, colic pain, and perianal erythema. She was admitted to the pediatric hospital emergency room, due to a suspected diagnosis of allergy to cow’s milk proteins, and she was fed with hydrolyzed formula. Pyloric hypertrophy was also ruled out by abdominal ultrasound. Empirical antibiotic therapy with amoxicillin-clavulanic was started, after extracting blood and urine cultures, and maintained until complete results of blood tests and cultures, which showed severe anemia without other infection parameters.

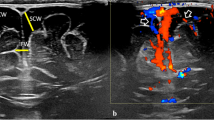

She progressed favorably with disappearance of vomiting and did mucous stools that tested negative to occult blood test. After 3 days of admission, intermittent gaze deviation to the left was detected, and because of this, along with the initial anemia of 6.6 g/dL, a brain ultrasound was requested. The transfontanellar ultrasound showed left intraparenchymal hemorrhage. A brain CT (Fig. 3) was immediately performed, confirming cerebral hemorrhage in the left Sylvian region, with a SAH component, and associated with left temporoparietal edema. The initial suspected diagnosis was a vascular malformation. The patient did not show signs or symptoms of intracranial hypertension at that moment, and hemostasis was unaltered. With these clinical and radiological findings, transfer to the pediatric ICU was requested.

Upon her arrival at our ICU, there were an evident tendency to deviated gaze to the left, slight weakness of the right limbs, with spontaneous mobility and good muscle tone. There was no asymmetry of the cranial nerves, active and reactive, and there were normal reflexes and good suckling.

Angiography was performed (Fig. 4) showing a middle cerebral artery aneurysm. Surgical treatment was performed, with clipping and resection of the aneurysm, given its large size and associated thrombosis. Postoperative imaging tests with CT and brain ultrasound were performed, showing good flow in the MCA and stable parenchymal hematoma, with normal ventricular size. No other neurological signs did show in the posterior neurological explorations.

From the final diagnosis, after radiological tests, prophylactic treatment was started with intravenous LV 10 mg/kg/12 h and dexamethasone 0.3 mg/kg/day, in addition to oral nimodipine as a preventive treatment of associated SAH vasospasm, which was maintained for 21 days.

The patient did not present any complications during her admission. At hospital discharge, weakness of the upper and lower right limbs had disappeared, with no other neurological atypical signs. She did not present seizures at any moment.

Outpatient follow-up was planned, without reported complications in the first period. Approximately, 2 months after diagnosis, an episode of sudden death occurred during nighttime sleep at home. No autopsy was performed.

Biopsy of the resected aneurysm revealed a saccular aneurysm with signs of rupture and partial organization. Microscopically, a thinned arterial wall was observed with a great saccular dilation, which interrupted the normal structure. Elastic lamina was not observed in most sections of the vascular wall.

Discussion

There are only few cases described in the literature of cerebral hemorrhage secondary to aneurysmal rupture in early childhood. Several studies have reported that intracranial aneurysms in the pediatric population are frequently located distal to the circle of Willis [6]. Both of our patients had an aneurysm located at the distal level of the middle cerebral artery.

In addition to being an infrequent entity in infants, the initial symptoms usually are nonspecific, entailing a difficult diagnosis. In the second case, for example, the final diagnose was not suspected until neurological symptoms appeared, the third day of admission.

Regarding treatment, both options, surgery and embolization, are valid alternatives, and the decision will depend on the location and characteristics of the aneurysm, in addition to the experience of the hospital center professionals [5]. Aneurysms located in the MCA are particularly difficult to treat in children because they are often spindle shaped, giant in size, and generally cannot be treated with a single direct clip or single intravascular coil.

A review of 1120 children [7] concluded that although the risk of stroke or postoperative bleeding is similar in both treatment groups, in-hospital mortality is higher in patients with surgical clipping compared to endovascular treatment. However, the long-term effect of endovascular embolization in pediatric patients is not known, due to the small number of patients treated with this technique. Furthermore, fewer postoperative seizures are observed after surgery than after endovascular treatment [8].

Surgical treatment was chosen in our two patients. Case 2 had a giant fusiform and thrombosed aneurysm, which required clipping and resection. This patient suffered from sudden death at home 2 months after the intervention. No autopsy was performed, but the main suspected diagnosis was a midterm postoperative rebleeding.

Epileptic seizures can appear both at diagnosis and after treatment [4, 8]. Our first case presented with seizures of complex management that persist until now.

Cerebral vasospasm is recognized as a significant risk factor for poor outcome after SAH in adult patients [2]. A systematic review in adults [9] indicates that treatment with oral calcium antagonists reduces the risk of poor neurological outcome (NNT = 19; 95% CI, 1 to 51). However, some studies concluded that it does imply poor evolution in children, and there is not a clear recommendation on the prevention or treatment of vasospasm in infants [10]. In our patients, treatment with oral nimodipine was administered for 21 days, without any complications noted.

Long-term prognosis of brain aneurysms is very uncertain in children. In previous studies, some authors described that children’s brains have greater plasticity and have a greater potential to recover from any insult, including brain hemorrhage, compared to adults [11, 12]. On the other hand, multiple studies found an association between ischemic or hemorrhagic brain injury in childhood, with the appearance of infantile spasms [13,14,15]. In our experience, patient 2 died of sudden death at home 2 months after the intervention, and the patient in case 1 presented with West syndrome probably secondary to the brain injury.

Conclusions

After reviewing the literature and exposing our two cases, we can conclude that, in the pediatric population, aneurysms are more frequently located distal to the circle of Willis. In MCA, they are frequently spindle shaped and distal, in which case they are difficult to treat with endovascular embolization, and surgery with clipping of the aneurysm is required. To date, there is more experience in the treatment of this kind of aneurysms with surgery; however, the use of embolization is becoming more common and widespread even for pediatric patients, so more studies are needed to assess the short- and long-term effects compared to open surgery.

The main complications following a ruptured aneurysm include rebleeding, seizures, neurological deficits, and death. Cerebral vasospasm contributes to poor outcome, but studies in children show a lack of experience to define the benefit of the use of calcium channel blockers or other treatments.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- SAH:

-

Subarachnoid hemorrhage

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- LV:

-

Levetiracetam

- ICHT:

-

Intracranial hypertension

- MR:

-

Magnetic resonance

- MCA:

-

Middle cerebral artery

References

Buis DR, van Ouwerkerk WJ, Takahata H, Vandertop WP (2006) Intracranial aneurysms in children under 1 year of age: a systematic review of the literature. Childs Nerv Syst. 22(11):1395–1409. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-006-0142-3 Epub 2006 Jun 29. PMID: 16807726

Goia A, Garrido E, Lefebvre M, Langlois O, Derrey S, Papagiannaki C, Gilard V (2020) Ruptured intracranial aneurysm in a neonate: case report and review of the literature. World Neurosurg. 140:219–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2020.05.018 Epub 2020 May 12. PMID: 32407915

Motohashi O, Kameyama M, Imaizumi S, Mino M, Naganuma H, Ishii K, Onuma T (2004) A distal anterior cerebral artery aneurysm in infant: disappearance and reappearance of the aneurysm. J Clin Neurosci. 11(1):86–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2003.09.004 PMID: 14642377

Chen R, Ren Y, Zhang S, You C, Liu Y (2018) Radiologic characteristics and high risk of seizures in infants with ruptured intracranial aneurysms: case report and review of the literature. World Neurosurg. 118:e772–e777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2018.07.049 Epub 2018 Jul 17. PMID: 30026150

Lanzino G, Murad MH, d'Urso PI, Rabinstein AA (2013) Coil embolization versus clipping for ruptured intracranial aneurysms: a meta-analysis of prospective controlled published studies. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 34(9):1764–1768. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A3515 Epub 2013 Apr 11. PMID: 23578672; PMCID: PMC7965621

Fulkerson DH, Voorhies JM, Payner TD, Leipzig TJ, Horner TG, Redelman K, Cohen-Gadol AA (2011) Middle cerebral artery aneurysms in children: case series and review. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 8(1):79–89. https://doi.org/10.3171/2011.4.PEDS10583 PMID: 21721893

Alawi A, Edgell RC, Elbabaa SK, Callison RC, Khalili YA, Allam H, Alshekhlee A (2014) Treatment of cerebral aneurysms in children: analysis of the kids’ inpatient database. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 14(1):23–30. https://doi.org/10.3171/2014.4.PEDS13464 Epub 2014 May 16. PMID: 24835049

Chen R, Zhang S, Guo R, Ma L, You C (2018) Pediatric intracranial distal arterial aneurysms: report of 35 cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 160(8):1633–1642. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-018-3574-0 Epub 2018 Jun 2. PMID: 29860558

Dorhout Mees SM, Rinkel GJ, Feigin VL, Algra A, van den Bergh WM, Vermeulen M, van Gijn J (2007) Calcium antagonists for aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007(3):CD000277. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000277.pub3 PMID: 17636626; PMCID: PMC7044719

Beez T, Steiger HJ, Hänggi D (2016) Evolution of management of intracranial aneurysms in children: a systematic review of the modern literature. J Child Neurol. 31(6):773–783. https://doi.org/10.1177/0883073815609153 Epub 2015 Oct 29. PMID: 26516106

Chadduck WM, Duong DH, Kast JM, Donahue DJ (1995) Pediatric cerebellar hemorrhages. Childs Nerv Syst. 11(10):579–583. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00300996 PMID: 8556724

Lõo S, Ilves P, Männamaa M, Laugesaar R, Loorits D, Tomberg T, Kolk A, Talvik I, Talvik T, Haataja L (2018) Long-term neurodevelopmental outcome after perinatal arterial ischemic stroke and periventricular venous infarction. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 22(6):1006–1015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpn.2018.07.005 Epub 2018 Jul 21. PMID: 30249407

Birca A, D'Anjou G, Carmant L (2014) Association between infantile spasms and nonaccidental head injury. J Child Neurol. 29(5):695–697. https://doi.org/10.1177/0883073813483901 Epub 2013 Apr 11. PMID: 23580697

Wallace A, Allen V, Park K, Knupp K (2017) Infantile spasms and injuries of prematurity: short-term treatment-based response and long-term outcomes. J Child Neurol. 32(10):861–866. https://doi.org/10.1177/0883073817712587 Epub 2017 Jun 21. PMID: 28635418

Venkatesan C, Millichap JJ, Krueger JM, Nangia S, Ritacco DG, Stack C, Nordli DR (2016) Epilepsy following neonatal seizures secondary to hemorrhagic stroke in term neonates. J Child Neurol. 31(5):547–552. https://doi.org/10.1177/0883073815600864 Epub 2015 Aug 24. PMID: 26303411

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Funding

The project was done with no specific support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YR, MM, EI, AM, and VM contributed to the conceptualization and designed of the study and drafted the initial manuscript. Also, all authors contributed to revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was not required for this study in accordance with national guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained from a parent or guardian for participants under 18 years old.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from a parent or guardian for participants under 18 years old, for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rubio Atienza, Y., Ibiza Palacios, E., del Peral Samaniego, M.P. et al. Intraparenchymal brain hemorrhage due to rupture of aneurysm in infants: report of two cases. Egypt Pediatric Association Gaz 70, 19 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43054-022-00111-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43054-022-00111-4