Abstract

Background

Thyroid hormones are essential for fetal growth and the central nervous system development. Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) is the key regulatory hormone. Their levels are quite dynamic in the perinatal period and are influenced by multiple factors. These factors should be taken into consideration during newborn screening. This study aimed to observe the impact of maternal and neonatal factors on neonatal TSH status.

Results

Neonatal TSH (nTSH) depicted a positive correlation with parity (p = 0.066) while negative correlation recorded with maternal blood haemoglobin (p = 0.007) among maternal factors.

New-born length (p = 0.027) and birth weight (p < 0.001) exhibited a negative correlation with nTSH among neonatal factors.

Conclusions

This study concludes that among all the maternal and neonatal factors, birth weight shows the most influence on nTSH. However, the effect may be compounded by other factors. As these risk elements rarely occur singly, it is often difficult to find the exposure which confer the risk on children. These factors should be considered while interpreting the result of the screening program.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Thyroid hormones are essential for fetal growth and development, particularly for the central nervous system. During the central nervous system development, thyroid hormone assists in the migration, differentiation, and proliferation of neuronal cells [1]. Thyroid hormone levels are quite dynamic in the perinatal period and are influenced by multiple factors. Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) is the key regulatory hormone that regulates the adequate production of thyroid hormones (T3 and T4) in the thyroid gland and their active conversion in the periphery. By the time the infant presents with symptoms of thyroid disorders, the levels are grossly deranged and might have resulted in irreversible sequelae. It is of utmost importance that any minor change in thyroid levels should be diagnosed early to prevent such clinical irreversibility. Hence, neonatal TSH levels are the primary target for screening thyroid-related disorders as the value changes to a greater fold when compared to the active thyroid hormones (T3 and T4).

In newborns, several maternal and neonatal factors such as maternal age, maternal anemia, parity of the mother, and fetus growth during the gestational period greatly influence TSH level [2]. These risk elements are commonly overlapping.

Some studies explored the impact of maternal and neonatal characteristics on thyroid hormones at birth. However, many of these studies were conducted with a small sample size. This study adds to that understanding with linear analysis of a large sample size. This study aimed to observe the impact of maternal and neonatal factors on neonatal TSH status.

Methods

The retrospective observational study was conducted among newborns delivered or admitted within 2 years in a tertiary care institute. The study started after being approved by the institute ethics committee. A consent waiver was approved for the study. A total of 1216 newborns were investigated for newborn screening for neonatal-TSH (nTSH) levels within 48–72 h of birth. TSH was analyzed on dried blood spot by fluorometric enzyme immunoassay which was validated by EQAS programme from centers for disease control and prevention (CDC). Data were collected from the medical record section and entered in a predesigned and pilot-tested questionnaire. The maternal factors included the demographic profile, clinical and obstetric history. Neonates’ anthropometric variables at birth and clinical details were noted as neonatal variables. Birth records with incomplete information, stillbirths, and death during the newborn period were excluded.

The data analysis was done by SPSS version 20. Log-transformation was performed for converting the non-normal to normalized data. The continuous variables were presented as mean and standard deviation (SD). Linear regression was conducted on the transformed variables to evaluate the interrelationship between the variables with nTSH, followed by multiple hierarchical regression analysis. This data has also been presented in a different paper as the analysis was diverse and not compatible with being accommodated in one article [3].

Results

A total of 1216 newborn were included in the study. The mean and the range of the variables of the study population are mentioned in Table 1. The percentages of babies born with birth weight of less than 1000 g (0.4%), 1000 to 1500 g (3.54%), and 1500 to 2500 g (26.81%). nTSH exhibited a wide range from 0.46 to 87.80 mIU/L (Table 1).

Relationship of maternal factors with nTSH

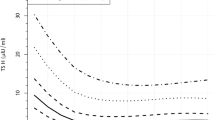

The regression coefficients to depict the interrelationship between the variables with nTSH are delineated in Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6, Table 2. The value of the regression coefficient for ANC check-ups after anti-log (Fig. 1) reflected that for every 1-unit change in ANC check-ups, nTSH value changes (decreases) by 1% (p = 0.066).

As showed in Fig. 2, nTSH depicted a positive correlation (p = 0.457) with maternal age. The value rises by 0.06% with every 1% change in maternal age. A 10% change in maternal age also affected birth weight by 0.6% (p = 0.457). Maternal blood haemoglobin values recorded significant negative correlation (p = 0.007) (Fig. 3). For every unit (in percent) change of mother’s hemoglobin level, the nTSH value recorded a change of 0.3%. If maternal hemoglobin changes from 8 g/dl to 8.8 g/dl, nTSH would change by 3%. The value of the regression coefficient for parity after anti-log is 1% (Fig. 4). It indicated that for every 1 unit increase in parity, nTSH increases by 1% (p = 0.066). Unlike maternal age, gestational age recorded a negative relationship with nTSH (p = 0.156). As denoted in Fig. 5, for every 1% increase in gestational age, nTSH decreased by 0.23%. Similarly, for every 10% increase in gestational age, birth weight reduced by 2.3 % (p = 0.156).

Relationship of neonatal factors with nTSH

As illustrated in Figs. 6, 7, and 8, all the three neonatal factors, length, head circumference, and birth weight, exhibited a negative correlation with nTSH (Table 2). Every unit change in length resulted in a significant shift in nTSH level (0.03%, p = 0.027). Similarly, a unit change in birth weight lowered nTSH values by 0.19% (p < 0.001). With every unit change in head circumference, nTSH altered by 2.6% (p = 0.978).

As seen by the B coefficients (Table 2), the independent variables of maternal hemoglobin, birth weight, and length at birth lead to only minor changes in the value of TSH. As seen by R2 minimal variability in TSH value is predicted by the above variables, with the most variability being predicted by birth weight (1.1%).

Discussion

Relation between TSH and maternal and neonatal demographic factors has received less attention as compared to other factors. Identifying factors that influence TSH variability in infants may help understand abnormal thyroid level contributors at birth. As hypothesized, the newborn screening data were analyzed to study the effect of various maternal and infant factors on the nTSH of newborns. This study suggests that nTSH is influenced somewhat by various maternal and neonatal characteristics. It could be due to the interplay of different other factors for adequate thyroid functioning.

Maternal factors

The nTSH value decreases with improvement in ANC check-ups (Fig. 1); this could be a proxy of improved antenatal care and nutrition. Deficiency of dietary iodine is a common cause of congenital and transient hypothyroidism in newborns. Maternal thyroid disease can also cause a suppression of thyroid function in the newborn. During ANC check-ups, thyroid disorders and iodine deficiency are diagnosed and treated, which improves the maternal condition and decreases the risk of thyroid disorders in newborns.

The present study evidenced an increase in nTSH with advanced maternal age (Fig. 2). A study from a rural center in South India demonstrated increased cord blood TSH with advancing maternal age [4]. A prospective cohort study in China also reported similar findings [5]. Another study by Lee et al. reported no significant association between maternal age and nTSH concentration [6].

A novel finding in our study was that for every 1% increase or decrease in hemoglobin levels, nTSH decreases or increases by 0.31% (Fig. 3), respectively. nTSH exhibited a significant inverse relationship with maternal hemoglobin (Table 2). The possible mechanism in this is impairment of heme-dependent thyroid peroxidase (TPO) enzyme in an iron-deficient state, limiting thyroid hormone synthesis [7].

It was seen that for every 1 unit increase in parity, nTSH gets elevated by 1% (Fig. 4). On the contrary, in another study, inverse relation was observed between parity and TSH of newborns [2]. Many studies have reported that first babies have higher nTSH levels than subsequent babies [8,9,10]. The difference may be due to the analysis of TSH in cord blood samples in their study. In contrast, some studies reported no differences in nTSH level according to birth order [11, 12].

Neonatal factors

For every 1% increase in gestational age, nTSH decreases by 0.23% (Fig. 5). Many previous studies have reported that nTSH levels increase with increasing gestational age [4, 11, 13, 14]. However, an inverse relationship has also been reported [15, 16], and several other studies have reported no difference in nTSH levels with gestational age [6, 12, 17, 18]. A likely explanation would be that the hypothalamic-pituitary response matures with the increase in gestational age. Impaired hypothalamic-pituitary responsiveness is seen in premature infants [19].

nTSH depicted a significant inverse correlation with every unit percent increase in length at birth. nTSH was found to be reduced by 0.03% (Fig. 6). Some studies showed no relation between birth length and nTSH levels [6].

The present study revealed a negative correlation with head circumference. With every unit percent change in head circumference, nTSH was expected to alter by 2.6% (Fig. 7). Lee SY found no association between head circumference and newborn TSH [6].

A significant negative correlation was observed between birth weight and nTSH level in this study. With every 1% increase in birth weight, nTSH was expected to decrease by 0.19% (Fig. 8). The findings agree with the results of Korada M et al., Rao PT et al., Lain SJ et al., and Sahoo et al. [12, 14, 15, 20]. Romagnoli C et al. and Lee SY et al. noted no significant influence of birth weight on nTSH [6, 21]. Birth weight, length, and head circumference are all associated with gestational age. As gestational age increases, growth parameters also increase. So, it is not surprising that hypothalamic-pituitary response is also positively correlated with the above factors.

During pregnancy, many physiological changes occur. Firstly, maternal total or bound thyroid hormone levels increase with serum concentration of thyroid-binding globulin. Second, the level of TSH decreases in early pregnancy because of weak stimulation of TSH receptors caused by human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) during the first 12 weeks of gestation. Thyroid hormone secretion is thus stimulated, and the resulting increased serum free thyroxine (T4) levels suppress hypothalamic thyrotropin-releasing hormone, which in turn limits pituitary TSH secretion. In the later stage of pregnancy, TSH levels return to baseline values and progressively increase in the third trimester related to placental growth and production of placental deiodinase. These physiologic changes should be responsible for the decrease in TSH of the newborn with improvement in gestation and growth parameters [22].

Conclusions

Our data showed that birth weight shows the most influence on nTSH among the maternal and neonatal factors. However, the effect may be compounded by other factors, and these factors should be considered while interpreting the result of the screening program.

The main strength of our study was the large sample size, which yielded a very high statistical power. The scatter plot, linear regression, and multiple hierarchical regression analysis performed is another strength, which provides the direction of the significant value of the parameters analyzed. The limitation of our study was that we did not assess the T4 and iodine status of the mother, which has a considerable impact on the thyroid status of both mother and newborn. Another limitation was that this was a retrospective study. Prospective study can give more idea about impact of these elements on TSH.

Availability of data and materials

Data will be made available by the corresponding author to the editor after a request email from the editor. The reason for sharing the data should be justified and it will be shared after all the authors approve the same.

Abbreviations

- TSH:

-

Thyroid-stimulating hormone

- nTSH:

-

Neonatal thyroid-stimulating hormone

- ANC:

-

Antinatal care

- TPO:

-

Thyroid peroxidase

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- hCG:

-

Human chorionic gonadotrophin

References

Bernal J (2005) Thyroid Hormones and Brain Development. Vitam. Horm. 71:95–122

Herbstman J, Apelberg BJ, Witter FR, Panny S, Goldman LR (2008) Maternal, infant, and delivery factors associated with neonatal thyroid hormone status. Thyroid 18:67–76

Patel S, Verma NR, Padhi P, Naik T, Nanda R, Naik G, Mohapatra E (2021) Retrospective analysis to identify the association of various determinants on birth weight. J Family Med Prim Care 10(1):496–501. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1493_20. Epub 2021 Jan 30

Raj S, Baburaj S, George J, Abraham B, Singh S (2014) Cord blood TSH level variations in newborn - experience from a rural centre in southern india. J. Clin. Diagnostic Res. 8:18–20

Zhang Y et al (2018) Effect of maternal and neonatal factors on neonatal thyroid stimulating hormone: Results from a population-based prospective cohort study in China. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 49:151–156

Lee SY (2016) Perinatal factors associated with neonatal thyroid-stimulating hormone in normal newborns. Ann. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 21:206–211

Zimmermann MB, Burgi H, Hurrell RF (2007) Iron deficiency predicts poor maternal thyroid status during pregnancy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 92:3436–3440

Gupta A, Srivastava S (2014) B. A. Cord blood thyroid stimulating hormone level--interpretation in light of perinatal factors. Indian Pediatr 51:32–36

Lakshminarayana S, Sadanandan N, Mehaboob A, Gopaliah L (2016) Effect of maternal and neonatal factors on cord blood thyroid stimulating hormone. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 20:317–323

Ryckman KK, Spracklen CN, Dagle JM, M. (2014) J. Maternal factors and complications of preterm birth associated with neonatal thyroid stimulating hormone. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. Sep 20:929–938

Trumpff C et al (2015) Neonatal thyroid-stimulating hormone level is influenced by neonatal, maternal, and pregnancy factors. Nutr. Res. 35:975–981

Sahoo PK, Swain A, Sahoo G, Mohanty S, Barik K (2020) Newborn screening for congenital hypothyroidism in institutional set up in an urban area in odisha. Int. J. Curr. Res. Rev. 12:179–182

Vandevijvere S et al (2012) Neonatal thyroid-stimulating hormone concentrations in belgium: a useful indicator for detecting mild iodine deficiency? PLoS One 7:3–8

Lain SJ et al (2015) Using record linkage to investigate perinatal factors and neonatal thyroid-stimulating hormone. J. Paediatr. Child Health 51:620–625

Rao DPT et al (2015) Determinants of thyroid function in neonates at birth. Pediatr. Rev. Int. J. Pediatr. Res. 2:30–36

Ng SM et al (2011) Multivariate analyses of factors that affect neonatal screening thyroid stimulating hormone. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 24:727–732

Miyamoto N et al (1991) Influence of Mode of Delivery on Fetal Pituitary-Thyroid Axis. Pediatr. Int. 33:363–368

Mohammad A, Roya K, Ziba F, Azadeh E, Mahin H (2013) Influence of perinatal factors on thyroid stimulating hormone level in cord blood. Adv. Biomed. Res. 2:48

Chung HR et al (2009) High incidence of thyroid dysfunction in preterm infants. J. Korean Med. Sci. 24:627–631

Korada M, Pearce MS, Avis E, Turner S, Cheetham T (2009) TSH levels in relation to gestation, birth weight and sex. Horm. Res. Paediatr 72:120–123

Romagnoli C, Currò V, Luciano R, Zecca E, De Carolis MP, Tortorolo G, Tomarchio S, Alessandrini L, Fiore L (1982) Hypothyroxinemia in the low birth-weight infant in the screening of congenital hypothyroidism. Med. Surg. Pediatr 4(6):679–684

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2020) Thyroid disease in pregnancy: ACOG practice bulletin, number 223. Obstetr Gynecol 135:e261–e274

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

Not applicable

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NRV: manuscript preparation and drafting the article. GN: analysis and interpretation of data. SP: concept and design of study, definition of intellectual content, and final approval of the version to be published. PP: concept and design of study. TN: concept and design of study. RN: review and editing of manuscript. Manuscript has been read and approved by all the authors and requirements for authorship as stated earlier in this document have been met. Each author believes that the manuscript represents honest work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approved from Institutional ethical committee, AIIMS, Raipur (Reference No. AIIMSRPR/IEC/2016/21). Informed written consent has been taken. Ethical statement was mentioned in method section.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Verma, N.R., Naik, G., Patel, S. et al. A detailed observational study of maternal and neonatal variables affecting the thyroid-stimulating hormone levels in neonates. Egypt Pediatric Association Gaz 69, 36 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43054-021-00080-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43054-021-00080-0