Abstract

Background

Bochdalek hernia is the most common type of congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) resulting from postero-lateral diaphragmatic defect. Hepatic heterotopia is very rarely associated with CDH, and hepatic herniation favors the worst prognosis.

Case presentation

We present a case of a neonate diagnosed with right Bochdalek hernia (BH) with anomalous hepatic lobe heterotopia. Intra operatively, mal-rotated loops were also found to be herniating in the right hemithorax. The mal-rotated loops were reduced back into abdomen after performing Ladd’s procedure and diaphragmatic defect was repaired over the anomalous liver lobe. Baby was discharged on 7th postoperative day and follow-ups showed good recovery.

Conclusion

This case report discusses the presentation, classification, and significance of this association. Our case report is noteworthy as Bochdalek hernia is very rarely associated with anomalous hepatic lobe.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

CDH is a defect in diaphragm resulting in abnormal development and maturation of lungs because of protrusion of abdominal contents through the hernia. The overall incidence of CDH is approximately 5–8/10,000 with slight male predominance [1, 2]. BH, which is the most common type of CDH (70–75%), results from defect in postero-lateral diaphragm [3]. With a controversial embryological basis, CDH has multifactorial etiology in which environmental and nutritional deficiencies have major roles [4]. Isolated CDH has better prognosis than CDH with multiple anomalies, especially hepatic herniation favors the worst prognosis [5, 6]. Here, we present a case of 3-day-old neonate with right BH associated with herniation of bowel loops and an anomalous lobe of liver through the defect.

Case presentation

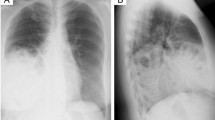

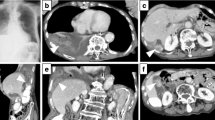

A 3-day-old baby was shifted to the NICU with respiratory distress and decreased O2 saturation. Baby was appropriately resuscitated with IV fluids to correct dehydration and O2 support. Antibiotic prophylaxis was also given. Baby was delivered by Normal Vaginal Delivery [NVD] with good APGARs at the time of birth. Birth weight was 3.1 kg. Routine blood investigations were normal. Babygram was obtained in PA as well as in lateral view (Figs. 1 and 2) which showed cystic lucencies (suggesting bowel loops) within the right hemithorax which appeared to be in continuation with the right abdominal cavity through the defect in right diaphragm. These lucencies were causing the contralateral mediastinal shift. Left lung demonstrated small nodular opacities peculiarly in lower zone. Left costophrenic [CP] angle was acute while right CP angle was not discretely visualized.

Pre-operatively, baby was intubated as he was tachypneic with low oxygen saturation. He was operated on 4th day of life by performing laparotomy with right upper transverse incision. During the operation, a right postero-lateral diaphragmatic defect was noted. Through the defect, mal-rotated gut loop and an anomalous structure were seen herniating into right hemithorax. We followed the anomalous structure and found it to be springing from liver. The mal-rotated loops were corrected by Ladd’s procedure and appendectomy was done. Loops were then reduced back from the sac into the abdomen and the sac was unreservedly excised. The diaphragmatic defect was repaired over the accessory hepatic lobe after reducing it back to the abdomen and posterior leaflet of diaphragmatic remnant was sutured to the strong anterior diaphragmatic muscles. The diaphragm was sutured from inside to the intercostal muscles with interrupted prolene 3–0 suture and a chest drain was left.

Postoperatively, baby was kept on Mechanical ventilation for 7 h and then weaned off to CPAP. On 3rd postoperative day, baby was weaned off to Head Box Oxygen. Feeding was gradually started, and right-sided chest drain was removed on 6th postoperative day because of discharge. Baby was discharged on 7th postoperative day. On 1 week follow-up post-discharge, baby was tolerating oral feeds quite well and his neonatal reflexes were intact.

Discussion

The diaphragm is formed by the fusion of several embryonic components which include the septum transversum, pleuroperitoneal membranes, esophageal mesentery, and body wall mesoderm [7]. A congenital diaphragmatic hernia occurs when the pleuroperitoneal canal fails to close by 8th week of fetal gestation [8]. The pathway of abnormal embryonic development leading to congenital diaphragmatic hernia is still incompletely understood. In the embryonic development period, fusion defects of the diaphragm can occur, resulting in postero-lateral defects (Bochdalek Hernia 70–75%), anterior-retrosternal defects (Morgagni Hernia 4%), and hiatal hernias and septum transversum defects (1%) [9]. A BH is a congenital posterior lateral diaphragmatic defect resulting from a failure of the retroperitoneal canal membrane to fuse with the dorsal esophageal mesentery and the body wall [10], Vincent Alexander Bochdalek described the fusion defect of the postero-lateral foramina of the diaphragm in 1848 [11]. The size of the hernia defect is variable and can range from 1 cm to almost complete agenesis of the hemidiaphragm. These hernias may contain stomach, spleen, colon, omentum, and small bowel. The fact that the left postero-lateral diaphragm closes after the right side may explain why the majority (~ 90%) of Bochdalek hernias occur on the left side. Right sided hernias are much rare and can involve the liver [12]. The literature on Bochdalek hernia in association with hepatic heterotropia in infants is rather limited, with very few cases reported. The finding of hepatic heterotopia in association with a congenital diaphragmatic hernia is a rare occurrence and has been limited to few case report studies. Hepatic heterotopia can be classified into four main types: (1) a large accessory lobe of liver connected to liver by a stalk; (2) a small accessory lobe of liver connected to liver surface; (3) Ectopic liver without any connection to, forming a macroscopically identifiable nodule; (4) microscopic ectopic liver tissue [13]. Types 2 and 3 have been reported with congenital diaphragmatic hernia, and our patient had type 2 hepatic heterotopia in the form of accessory lobe. The combination of CDH with an accessory liver is an extremely rare condition. Correction of congenital diaphragmatic hernia is possible in utero. However, liver involvement leads to significantly high mortality [14]. To the best of our knowledge the association of accessory liver in combination with CDH in an infant is not the common occurrence. Aside from being fascinating incidental finding, the pediatric general surgeon should be aware of the clinical significance of this association. Firstly, associating this finding with cardiac anomaly as well as pericardial defect warrants careful examination and assessment of the pericardium through cardiac echocardiography, which is a routine workup of congenital diaphragmatic hernia [15]. Secondly, knowledge of this association is helpful intra operatively to delineate the anatomy and facilitate the proper surgical repair of the diaphragmatic defect. Third, ectopic liver lobe may be complicated by secondary pathological condition such as torsion, infarction, and bleeding [16]. While these complications were not reported in this case, it is essential for the surgeon to be aware of these Risks. Lastly, presence of hepatic heterotopia-like accessory liver lobe contribute to congenital diaphragmatic recurrence, thus stressing the importance of long term follow up for this particular anomaly is advised.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this case report highlights the association of congenital diaphragmatic hernia with hepatic accessory lobe. The pediatric general surgeon should be aware of this association, given its perioperative, intraoperative, and postoperative complications. Further data is required to quantify the exact risk of congenital diaphragmatic hernia associated with accessory liver lobe.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CDH:

-

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia

- BH:

-

Bochdalek hernia

- NICU:

-

Neonatal Intensive Care Unit

- NVD:

-

Normal vaginal delivery

- PA view:

-

Posterior-anterior view

References

Yang W, Carmichael SL, Harris JA, Shaw GM (2006) Epidemiologic characteristics of congenital diaphragmatic hernia among 2.5 million California births, 1989-1997. Birth defects research. Part A, Clinical Mol Teratology 76(3):170–174. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdra.20230

McGivern MR, Best KE, Rankin J, Wellesley D, Greenlees R, Addor MC et al (2015) Epidemiology of congenital diaphragmatic hernia in Europe: a register-based study. Archives of disease in childhood. Fetal and neonatal edition 100(2):F137–F144. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2014-306174

Veenma DC, de Klein A, Tibboel D (2012) Developmental and genetic aspects of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Pediatr Pulmonol 47(6):534–545 https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.22553

Beurskens LW, Tibboel D, Steegers-Theunissen RP (2009) Role of nutrition, lifestyle factors, and genes in the pathogenesis of congenital diaphragmatic hernia: human and animal studies. Nutr Rev 67(12):719–730 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.2009.00247.x

Tennant PW, Pearce MS, Bythell M, Rankin J (2010) 20-year survival of children born with congenital anomalies: a population-based study. Lancet (London, England) 375(9715):649–656 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61922-X

Metkus AP, Filly RA, Stringer MD, Harrison MR, Adzick NS (1996) Sonographic predictors of survival in fetal diaphragmatic hernia. J Pediatr Surg 31(1):148–152 10.1016/s0022-3468(96)90338-3

Schumpelick V, Steinau G, Schlüper I, Prescher A (2000) Surgical embryology and anatomy of the diaphragm with surgical applications. Surg Clin North Am 80(1):213–2xi. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70403-5

Sadler TW (1985) Study guide and self-examination review for Langman's medical embryology

Wenzel-Smith G (2013) Posterolateral diaphragmatic hernia with small-bowel incarceration in an adult. South African journal of surgery. Suid-Afrikaanse tydskrif vir chirurgie 51(2):73–74 https://doi.org/10.7196/sajs.1320

Salaçin S, Alper B, Cekin N, Gülmen MK (1994) Bochdalek hernia in adulthood: a review and an autopsy case report. J Forensic Sci 39(4):1112–1116

Haller JA Jr (1986) Professor Bochdalek and his hernia: then and now. Prog Pediatr Surg 20:252–255 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-70825-1_18

Ayane GN, Walsh M, Shifa J, Khutsafalo K (2017) Right congenital diaphragmatic hernia associated with abnormality of the liver in adult. The Pan African Med J 28:70. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2017.28.70.11249

AlFraih Y. (2021). Congenital diaphragmatic hernia with hepatic heterotopia. Journal of pediatric surgery case reports. 2021;64:101738

Harrison MR, Adzick NS, Bullard KM, Farrell JA, Howell LJ, Rosen MA, Sola A, Goldberg JD, Filly RA (1997) Correction of congenital diaphragmatic hernia in utero VII: a prospective trial. J Pediatr Surg 32(11):1637–1642 10.1016/s0022-3468(97)90472-3

Patel Y, McNally J, Ramani P (2007) Left congenital diaphragmatic hernia, absent pericardium, and liver heterotopia: a case report and review. J Pediatr Surg 42(5):E29–E31 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.03.033

Mito K, Amano Y, Oshiro H, Matsubara D, Fukushima N, Ono S (2019) Liver heterotopia associated with congenital diaphragmatic hernia: two case reports and a review of the literature. Medicine 98(4):e14211 https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000014211

Acknowledgements

None to declare.

Funding

None to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors attest that they meet the current ICMJE criteria for authorship. WK and AS conceptualized and designed the study, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript, final editing of the manuscript.MM conceptualized and designed the study, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. AA conceptualized and designed the study, drafted the initial manuscript, and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Verbal and written informed consents were given by the patient’s parents for the publication of this case. A copy of written consent is available for the journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khan, W., Safi, A., Ahmad, A. et al. A case of Bochdalek hernia with anomalous hepatic lobe heterotopia-case report. Egypt Pediatric Association Gaz 69, 31 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43054-021-00075-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43054-021-00075-x

Cystic lucencies in right hemithorax

Cystic lucencies in right hemithorax

Cystic lucencies in right hemithorax to be in continuation with the right abdominal cavity

Cystic lucencies in right hemithorax to be in continuation with the right abdominal cavity