Abstract

Background

Exposure to violence is associated with psychological distress, mental disorders such as depression, and suicidal behaviour. Most of the studies are conducted in the West, with limited publications from Asia. Thus, we conducted a scoping review of studies investigating the association between experiences of violence and later suicidal ideation/attempts from Asia in the twenty-first century.

Results

Many studies focused on domestic violence toward women in the Southeast Asian region. Sociocultural factors such as family disputes, public shaming, dowry, lack of education opportunities, and marriage life perceptions mediated the association. Many women exposed to violence and attempted suicide suffered from mental disorders such as depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress. The small number of suitable studies and the possible effect of confounders on participants were limitations in the review. Future studies would have to focus on specific types of violence and ethnoreligious beliefs.

Conclusion

Women in Asia exposed to violence appear to have an increased risk of suicidal behaviour and mental disorders. The early screening of psychological distress with culturally validated tools is essential for preventing suicides in Asian victims of violence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Suicide and attempted suicide are distinguished from other types of self-harming behaviours by their intent to die [1]. Vulnerabilities to attempt suicide differ in distinct communities. For example, among Asian university students, psychosocial variables such as living alone increase the likelihood of suicidal ideation, and adverse events like childhood sexual abuse were related to suicidal attempts [2]. Suicide-related research is mainly from the West, even though more than half of suicides occur in Asia [3]. Suicides are common in South Asian countries, and poisoning and hanging are the most common methods [4]. Millions attempt suicide worldwide, and distinct psychosocial variables such as intimate partner violence enhance women’s likelihood of suicide attempts [5].

Women are more prone to attempt suicide and self-harm behaviours than males, although the rate of completed suicide is much higher in men [6]. Furthermore, suicidal attempts are strongly linked to gender-based violence and cruelty against women in low- and middle-income nations [7]. According to a study conducted in Nepal, more than 60% of women who completed suicide had been physically abused [8]. Suicide attempts are fuelled by early marriage, early parenthood, gender disparities, and unfavourable financial and political conditions [9]. While physical assault increases the risk of suicidal attempts in married women, emotional violence, such as infidelity by the husband, jealousy by the husband, threats of divorce, threats of physical assaults, isolation from family members, and control and coercion by the husband, has a more significant impact [10]. Nondisclosure of domestic violence increases the risk of postpartum depression and suicide attempts [11]. Therefore, delay in addressing domestic violence represents a significant threat to women’s lives.

Understanding the variables that lead to suicide is essential to designing effective suicide prevention and reduction strategies. According to studies, survivors of domestic violence have a higher risk of suicide than others [12]. Domestic violence refers to a pattern of behaviour to gain authority or maintain power and control over a spouse, partner, girlfriend/boyfriend, or close family member [13]. Because of the reported frequency of domestic violence and the related physical and psychological morbidity and mortality, addressing domestic violence is a global public health concern [14]. According to a World Health Organization (WHO) study, domestic violence affects between 27.8 and 32.2% of women worldwide, with prevalence rates exceptionally high in Africa (45.6%), Southeast Asia (40.2%), and Eastern Mediterranean countries (36.4%) [15].

Domestic violence is prevalent worldwide, and most suicides occur in Asia. This scoping review aimed to explore and collate research studying the associations between experiences of violence at home to later suicidal behaviour, predominantly in women. As this has been studied extensively in the West, we focused on the Asian region and its relevant, unique sociocultural implications.

Methods

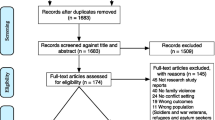

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) were used for the review [16]. A literature search was conducted for English-language articles from 1st January 2001 to 1st January 2022 (twenty-first century) regarding suicide, self-harm, and violence on PubMed, Google Scholar, and UBC Library. Searches were done using combinations of the following keywords: (violence [Title/Abstract]) AND (suicide [Title/Abstract]) OR (suicidal [Title/Abstract]) OR (self-harm [Title/Abstract]) AND (Asia [Text Word]) AND (English [Language]) NOT (review [Publication Type]) NOT (letter [Publication Type]). All relevant research articles were reviewed, and the information was retrieved and stratified based on epidemiology, evaluation, and follow-up. Several psychiatrists perused the findings, and the relevant literature was included.

The studies included in this scoping review are research investigating the link between suicide and/or self-harm and violence conducted in an Asian country. Reviews, dissertations, theses, and book chapters were omitted. Also, repeated publications, studies that did not meet the theme and association explored, and studies with incomplete results were excluded. Two consultant psychiatrists screened all the papers in the review, and a third psychiatrist intervened when a consensus could not be reached. The data was then recorded into an Excel sheet tailored to meet the study’s goals. The PRISMA flowchart in Fig. 1 shows the shortlisting process. Data such as publication year, region, country of the study, sample size, and main findings were collected by two reviewers using standard extraction tables. If there was a dispute, an arbitration mechanism was activated, and a third reviewer was required to reach a consensus.

Results

A total of 438 potentially relevant documents were identified through databases. After removing 226 duplicates, 212 articles were left. Hundred and five full-text articles were screened, 87 excluded, and 19 were included in the review. The 19 articles included in the review were peer reviewed and original. Sixteen of the articles were conducted in Southeast Asia; four were from India [17,18,19,20]; two each from Bangladesh [21, 22], Afghanistan [23, 24], and China [25, 26]; and one each from Sri Lanka [27], Nepal [8], Iran [28], South Korea [29], and the Philippines [30]. One study each from South-Asian immigrants in the UK [31] and multiple countries in Southeast Asia [32] and a study from several countries, which included South America, Asia, Africa, Oceania, and Europe, were included [9]. The majority of the studies [13] had a sample size of fewer than 1000 participants, six had over 1000 participants, and only one study had over 4000 participants. The review included ten cross-sectional studies, four case and control studies, one randomised control study, and an autopsy case series. Two-thirds of the studies [12] studied female participants, six studied both males and females, and one did not mention the gender studied. The majority did not mention participants’ religion; three studied Muslims and three mixed. The reviewed studies’ main finding was termed suicidal behaviour in 12 studies, deliberate self-harm, and suicide in 3 studies.

Of the 19 studies included in the review, eight did not mention the sample’s age group, six used a mixed age group, and five used the adult population only. Ten articles did not mention the associated factors explored; however, six mentioned mental health disorders as the main associated factor. One each mentioned racial discrimination and lack of support as associated factors. Detailed characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Discussion

Our review found exposure to violence as a risk factor for suicide and suicidal behaviour. The participants were predominantly female in the articles we reviewed. We found that females are more commonly the victims of domestic violence, and across all studies, suicidal behaviours such as suicidal thoughts and ideation were the most common findings. Suicide is one of the leading causes of morbidity in women worldwide, although little is known about its prevalence and modifiable risk factors in Asian countries.

In our review, the most common risk factor associated with suicide and/or suicidal behaviour due to domestic violence was mental illness and/or psychological distress [27, 29, 30, 33]. Domestic violence has significant health consequences for women, children, and families. It adds to the global disease burden regarding women’s morbidity and mortality, including psychological trauma, depression, suicide, and murder. The mental health repercussions of violence against women include behavioural difficulties, sleeping issues, eating disorders, depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, self-harm, suicide attempts, low self-esteem, and substance use disorder [20].

Most of the included studies [14] were conducted in Southeast Asia, where the domestic violence rate is relatively high. A South Indian study found that nearly 80% of the women studied were exposed to domestic violence, which occurs in the sociocultural context of dowry and endowments [35]. Domestic violence against women and girls is the most widespread human rights violation globally, affecting approximately one-third of women in their lives, with most cases stemming from intimate relationships [15]. Women’s empowerment, gender equality, and achieving sustainable development goals are all hampered by domestic violence. Domestic violence wreaks havoc on people’s lives, shatters families and communities, and stops personal growth. Age, race, caste, poverty, class, sexual orientation, gender identity, disabilities, religion, indigeneity, nationality, immigration status, and other factors make women vulnerable to assault [36].

Sexual violence was significantly associated with depression and psychological abuse and the risk of femicide with suicidal behaviour [33]. In Asia, many cultural factors affect suicidal behaviour, such as lack of opportunities for education, poverty, migrant labour, and family disputes causing shame [8]. These cultural attributes persist even in-migrant South Asian populations in the West [31]. The method of attempting suicide varies in different Asian regions, from self-immolation in Iran to self-poisoning in Sri Lanka [27, 28]. Domestic violence is associated with depressive disorder in women [37]. Early screening for psychological distress and mental disorders and improving access to services are essential in preventing suicides in women exposed to violence.

Limitations of the review include the small number of studies from Asia, heterogeneity of methodology, and the potential effect of confounders. Also, the relationship between specific aspects of violence and suicidal behaviour was not evident, as many of the participants had experienced physical, emotional, and sexual trauma. Furthermore, as most included research, self-report methods are subjective to recall bias and underreporting violence [20, 38]. Future studies would have to focus on relevant ethnic, religious belief systems, and types of violence to produce relevant data for developing prevention strategies. Furthermore, one study was of a South Asian community in the UK, and local cultural and legal factors may have affected the outcomes. Finally, since there are far fewer studies with male participants than with females, this finding should not be generalised to both genders.

Many Asian countries lack structured mental health legislation, and governments have allocated limited funds for psychiatric services [39]. Healthcare workers need to use culturally validated tools to detect conditions that link violence and suicidal behaviour in Asia, such as depression, anxiety, and general psychological stress [23, 24, 27, 29, 30]. For example, the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) has been used widely in many Asian regions and is deemed appropriately sensitive and specific to the required task [40].

Conclusion

Many women in Asia are vulnerable to violence, especially domestic violence in the context of local sociocultural factors. Limited studies in Asian communities show that exposure to violence increases the risk of suicidal behaviour and mental disorders, predominantly in women. Therefore, it is imperative that psychological distress is detected early using culturally validated tools, and that women in distress are supported effectively to prevent suicides in Asian countries.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author at reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- PRISMA:

-

Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses

References

Lester D, Fleck J (2010) What is Suicide? Will Suicidologists Ever Agree? Psychological Reports 106(1):189-192. https://doi.org/10.2466/PR0.106.1.189-192.

Peltzer K, Yi S, Pengpid S (2017a) Suicidal behaviours and associated factors among university students in six countries in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Asian J Psychiatr 26:32–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AJP.2017.01.019

Chen YY, Chien-Chang Wu K, Yousuf S, Yip PSF (2012) Suicide in Asia: opportunities and challenges. Epidemiol Rev 34(1):129–144. https://doi.org/10.1093/EPIREV/MXR025

Jordans MJD, Kaufman A, Brenman NF, Adhikari RP, Luitel NP, Tol WA, Komproe I (2014) Suicide in South Asia: a scoping review. BMC Psychiatry 14(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12888-014-0358-9/TABLES/1

Kazan D, Calear AL, Batterham PJ (2015) The impact of intimate partner relationships on suicidal thoughts and behaviours: a systematic review. J Affect Disord 190:585–598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.11.003

Suicide statistics | AFSP. (n.d.). Retrieved March 31, 2022, from https://afsp.org/suicide-statistics/

Devries KM, Mak JY, Bacchus LJ, Child JC, Falder G, Petzold M, Astbury J, Watts CH (2013) Intimate partner violence and incident depressive symptoms and suicide attempts: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. PLoS Med 10(5):e1001439. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PMED.1001439

Hagaman AK, Khadka S, Lohani S, Kohrt B (2017) Suicide in Nepal: a modified psychological autopsy investigation from randomly selected police cases between 2013 and 2015. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 52(12):1483–1494. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00127-017-1433-6.

Devries K, Watts C, Yoshihama M, Kiss L, Schraiber LB, Deyessa N, Heise L, Durand J, Mbwambo J, Janssen H, Berhane Y, Ellsberg M, Garcia-Moreno C (2011) Violence against women is strongly associated with suicide attempts: evidence from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health

Rahmani F, Salmasi S, Rahmani F, Bird J, Asghari E, Robai N, Asghari Jafarabadi M, Gholizadeh L (2019) Domestic violence and suicide attempts among married women: a case-control study. J Clin Nurs 28(17–18):3252–3261. https://doi.org/10.1111/JOCN.14901

Koirala P, Chuemchit M (2020a) Depression and domestic violence experiences among Asian women: a systematic review. Int J Womens Health 12:21. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S235864

Brown S, Seals J (2019) Intimate partner problems and suicide: are we missing the violence? J Inj Viol Res 11(1):53. https://doi.org/10.5249/JIVR.V11I1.997

Rakovec-Felser Z (2014) Domestic violence and abuse in intimate relationship from public health perspective. Health Psychol Res 2(3):1821. https://doi.org/10.4081/HPR.2014.1821

Modi MN, Palmer S, Armstrong A (2014) The role of violence against women act in addressing intimate partner violence: a public health issue. 23(3):253–259. https://doi.org/10.1089/JWH.2013.4387Https://Home.Liebertpub.Com/Jwh

García-Moreno C, Pallitto C, Devries K, Stöckl H, Watts C, Abrahams N (2013) Global and regional estimates of violence against women: prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/85239/9789241564625_eng.pdf.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, Moher D (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJ.N71

Chowdhury AN, Brahma A, Banerjee S, Biswas MK (2009) Pattern of domestic violence amongst non-fatal deliberate self-harm attempters: a study from primary care of West Bengal. Indian J Psychiatry 51(2):96. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.49448

Gururaj G, Isaac MK, Subbakrishna DK, Ranjani R (2010) Risk factors for completed suicides: a case-control study from Bangalore, India. 11(3):183–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/156609704/233/289706

Indu PV, Remadevi S, Vidhukumar K, Shah Navas PM, Anilkumar TV, Subha N (2020) Domestic violence as a risk factor for attempted suicide in married women. J Interpers Violence 35(23–24):5753–5771. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517721896

Sharma KK, Vatsa M, Kalaivani M, Bhardwaj D (2019) Mental health effects of domestic violence against women in Delhi: a community-based study. J Fam Med Prim Care 8(7):2522. https://doi.org/10.4103/JFMPC.JFMPC_427_19

Naved RT, Akhtar N (2008) Spousal violence against women and suicidal ideation in Bangladesh. Womens Health Issues 18(6):442–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.WHI.2008.07.003

Shah M, Ali M, Ahmed S, Arafat SMY (2017) Demography and risk factors of suicide in Bangladesh: a six-month paper content analysis. Psychiatry J 2017:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/3047025

Jewkes R, Corboz J, Gibbs A (2019) Violence against Afghan women by husbands, mothers-in-law and siblings-in-law/siblings: risk markers and health consequences in an analysis of the baseline of a randomised controlled trial. PLoS One 14(2):e0211361. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0211361

Paiman A, Khan M, Ali T, Asad N, Syed I (2019) Psychosocial factors of deliberate self-harm in Afghanistan: a hospital-based, matched case-control study. East Mediterr Health J 25(11) https://ecommons.aku.edu/pakistan_fhs_mc_psychiatry/127

Wu W, Zhang Y, Goldsamt L, Yan F, Wang H, Li X (2021) The mediating role of coping style: associations between intimate partner violence and suicide risks among Chinese wives of men who have sex with men. J Interpers Violence 36(11–12):NP6304–NP6322. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518814264

Yanqiu G, Yan W, Lin A (2011) Suicidal ideation and the prevalence of intimate partner violence against women in rural Western China. Violence Against Women 17(10):1299–1312. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801211425217

Bandara P, Page A, Senarathna L, Kidger J, Feder G, Gunnell D, Rajapakse T, Knipe D (2020) Domestic violence and self-poisoning in Sri Lanka. Psychol Med 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720002986

Dahmardehei M, Poor FB, Mollashahi G, Moallemi S (2014) Epidemiological study of self-immolation at Khatamolanbia Hospital of Zahedan. Int J High-Risk Behav Addict 3(1):13170. https://doi.org/10.5812/IJHRBA.13170

Kim GU, Son HK, Kim MY (2021) Factors affecting suicidal ideation among premenopausal and postmenopausal women. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 28(3):356–369. https://doi.org/10.1111/JPM.12679

Antai D, Anthony D (2014) Psychological distress and attempted suicide in female victims of intimate partner violence: an illustration from the Philippines context. J Public Ment Health 13(4):197–210. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMH-08-2013-0057/FULL/XML

Chew-Graham C, Bashir C, Chantier K, Burman E, Batsleer J (2002) South Asian women, psychological distress and self-harm: lessons for primary care trusts. Health Soc Care Community 10(5):339–347. https://doi.org/10.1046/J.1365-2524.2002.00382.X

Peltzer K, Yi S, Pengpid S (2017b) Suicidal behaviours and associated factors among university students in six countries in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Asian J Psychiatr 26:32–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AJP.2017.01.019

Peltzer K, Pengpid S (2017) Suicidal ideation and associated factors among students aged 13–15 years in Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) member states, 2007–2013. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 21(3):201–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/13651501.2017.1301486

Wu D, Yang T, Rockett I, Yu L, Peng S, Jiang S (2018) Uncertainty stress, social capital, and suicidal ideation among Chinese medical students: Findings from a 22-university survey. J Health Psychol 26:135910531880582.

Menon S (2020) The effect of marital endowments on domestic violence in India. J Dev Econ 143:102389. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JDEVECO.2019.102389

Focus areas: End violence against women | UN Women – Asia-Pacific. (n.d.). Retrieved April 3, 2022, from https://asiapacific.unwomen.org/en/focus-areas/end-violence-against-women and domestic violence against women. Soc Sci Med 73(1), 79–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SOCSCIMED.2011.05.006

Koirala P, Chuemchit M (2020b) Depression and domestic violence experiences among Asian women: a systematic review. Int J Womens Health 12:21. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S235864

Yoshihama M, Gillespie BW (2002) Age adjustment and recall bias in the analysis of domestic violence data: methodological improvements through the application of survival analysis methods. J Fam Viol 17(3):199–221. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016001211182

Sharan P, Sagar R, Kumar S (2017) Mental health policies in South-east Asia and the public health role of screening instruments for depression. WHO South-East Asia J Public Health 6(1):5. https://doi.org/10.4103/2224-3151.206165

Lee HH, Kim TH (2014) Screening depression during and after pregnancy using the EPDS. Arch Gynaecol Obstet 290(4):601–602. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00404-014-3334-1

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have contributed to writing and reviewing the manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shoib, S., Khan, S., Baiou, A. et al. Exposure to violence and the presence of suicidal and self-harm behaviour predominantly in Asian females: scoping review. Middle East Curr Psychiatry 29, 62 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43045-022-00225-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43045-022-00225-w