Abstract

Background

Infections with Toxoplasma gondii (Toxo), a protozoan that can infect the brain, have been reported to alter behavior in rodents and humans; several investigators have related Toxo infection to personality traits such as novelty seeking in humans. We investigated human personality traits in relation to Toxo in Egypt, where such infection is common.

Results

In a community-based sample of Egyptian adults (N = 255), Toxo infection were indexed by levels of IgG antibodies. Viruses like hepatitis C virus (HCV) have also been associated with cognitive dysfunction and mood disorders; therefore, HCV antibody titers were also assayed for comparison. The antibody levels were analyzed in relation to the Arabic version of the NEO personality inventory (NEO-FFI-3), accounting for demographic variables. No significant correlations were noted with Toxo or HCV antibody levels, after co-varying for demographic and socio-economic factors and following corrections for multiple comparisons.

Conclusions

Infection with Toxo or HCV infection was not associated with variations in personality traits in a sample of Egyptian adults. The possible reasons for the discordance with prior reported associations are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Toxoplasma gondii (Toxo), a protozoan organism, can infect all warm blooded animals. Felines serve as the definitive host. In some rodent models, Toxo-infected rats or mice show increased exploratory behavior and reduced fear of cats, potentially facilitating their capture by cats [1]. This exemplifies a mechanism through which infectious agents can ensure their survival by affecting the behavior of more complex hosts [2, 3].

Humans are accidental hosts for Toxo. Yet, Toxo can cause extensive pathology, including abortions, encephalitis, seizures, and deaths in immunosuppressed persons [4]. Infection can also occur in neonates [5]. Analogous to the rodent models, it has been reported that sub-clinical Tox infection, indexed by levels of antibodies to Toxo, is also associated with subtle changes in human behavior, such as proneness to road traffic accidents and suicide [6, 7] and even enduring changes in personality traits. Many of the behavioral changes are associated with infection are non-specific but pioneering observational and experimental studies by Dr. Flegr and his colleagues indicate more subtle variation [8], reviewed by [9] (Table 1). For example, changes in “novelty seeking,” self-control, and “superego strength” have been reported [10, 11]. Other investigators have reported increase in suspiciousness, particularly among women [12]. In summary, exposure to Toxo can be associated with accentuation of certain personality traits depending on the disease, duration of therapy, and psycho-social impact of the diagnosis [13].

The reported associations between Toxo infection and behavioral changes could be modulated by the effects of the parasite on neurotransmitters in the brain such as dopamine via parasite-encoded tyrosine hydroxylase) [14, 15]. The effects could also be related to direct toxic effects of the parasite on neural or non-neural tissues and the effects could be neutral or advantageous to the parasite in terms of survival, e.g., increasing the likelihood that infected hosts yield to feline predation thus Toxoplasma gains a reproductive advantage [16].

The potential effects of infectious agents on human host cognition and behavior not only have public health impacts, but they also raise important ethical and philosophical questions, such as the existence of free will [17] and whether geographical variation in infections could contribute to “modal” personality groups in different nations [18].

The studies with Toxoplasma also raise the possibility that similar or analogous behavioral changes could be induced by other agents that cause chronic infections in humans. Viruses can infect humans and herpes viruses are associated with cognitive dysfunction [19, 20]. Accumulating evidence also links infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) with human behavioral dysfunction. Though HCV is well known as a cause of hepatic diseases, virions have also been detected in the brain [21, 22]. HCV patients have abnormalities in cerebral metabolites and P300 evoked potentials, suggesting direct effects of HCV on the human brain [23, 24]. In addition, several studies have reported downregulated mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation genes and reduced expression of specific ribosomal protein genes in post-mortem brain tissue from HCV-seropositive patients [25]. We have recently reported on cognitive dysfunction in association with hepatitis C virus infection (HCV) [26]. Many investigators have reported increased prevalence of depression among HCV-infected individuals [27,28,29]. Others have reported increased prevalence of personality disorders among HCV-infected individuals, including prisoners as well as community dwelling samples [30,31,32,33]. The personality clusters associated with HCV infection include cluster-B personality disorders [34], as well as impulsiveness [35].

The majority of these studies have been conducted in developed nations, particularly among individuals reporting Caucasian ancestry. It is necessary to conduct similar studies in other ethnic groups in order to evaluate their generalizability. Therefore, we investigated the relationship between Toxo and HCV infection and personality traits using a cross-sectional design in Egypt where there is a relatively high prevalence of Toxo (40–60%) and HCV infections (14.7% %) [36, 37]. We selected a community-based sample in which rates of self-reported abuse of alcohol or illicit substances are low.

Methods

Participants

This is a cross-sectional study where we will recruit Egyptian people with age ranging from 21 to 62 years old. Participants signed an informed consent after the study procedures are explained to them. We assumed within group standard deviation of 1 and alpha = 0.05 using the GPower software. We estimated power at seropositivity (exposure) rates of around 50% for Toxoplasma, based on the expected age/ethnicity distribution of our sample. At these exposure levels, our sample of 250 individuals has over 80% power.

Inclusion criteria

-

1.

Egyptian nationality

-

2.

Age from 18 to 65

-

3.

Both genders

-

4.

Written informed consent

Exclusion criteria

-

1.

Presence of psychotic disorders

-

2.

Current alcohol or illicit substance abuse or substance abuse in the past 6 months (DSM IV criteria)

-

3.

Individuals who were unable to read or write

-

4.

Severe medical condition that would affect cognitive performance such as epilepsy, history of encephalitis or severe head trauma, or any other reported neurological disorder of the central nervous system

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee at Mansoura University and the Institutional Review Board at the University of Pittsburgh.

Clinical assessment

Standard for Clinicians’ Interview in Psychiatry (SCIP) [38]

A semi-structured questionnaire was administered to all participants to evaluate for the presence of psychopathology or presence of alcohol/substance abuse.

Sociodemographic data and medical history checklists

Sociodemographic data and medical history checklists were used to obtain demographic details, including occupation, handedness, level of education, and marital status, as well as history of medical disorders.

Arabic version of NEO Personality Inventory-Revised (NEO FFI-3) [39]

The NEO-FFI-3 is a 60 item version of the NEO-PI-3 that provides a brief, comprehensive measure of the five domains of personality, namely neuroticism (N), extraversion (E), openness to experience (O), agreeableness (A), and conscientiousness (C). It consists of five 12-item scales that evaluate each domain. The respondent is asked to respond along a five-point scale, varying from strongly disagree to strongly agree. The personality factors are defined by groups of correlated traits. By describing the individual’s standing on each of the 5 factors, the NEO inventories provide a comprehensive evaluation of an individual`s emotional, interpersonal, experiential, attitudinal, and motivational style. NEO-PI-3 domain scales and factors measure personality at this level; facet scales offer a more fine-grained analysis by measuring specific traits within each of 5 domains. The first step in interpreting a NEO-PI-3 profile is to examine the five domain scales to understand personality at the broadest.

Serological assays

Venous blood samples were obtained from all participants (10 ml), spun down and serum extracted and stored. IgG assays for antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii and hepatitis C were conducted and antibody levels were estimated [40, 41]. Venous blood samples were obtained from all participants and stored at – 80 °C. IgG antibodies to HCV were assayed in the serum or plasma using a commercial enzyme-linked fluorescent assay at the certified Pathology laboratories of the Mansoura School of Medicine (“http://www.biomerieux-diagnostics.com/vidas-hepatitis-panel”). Seropositivity was defined as HCV antibodies titer ˃ 1 as specified by the manufacturer. IgG antibodies to TOX were assayed together using solid-enzyme IgG immunoassays to estimate at the Stanley Laboratory of Developmental Neurovirology, Baltimore, Maryland [41]. Based on the distribution of TOX antibody levels, seropositivity was defined as IgG titer ˃ 2 units.

Statistical analysis

Initially, correlations between toxoplasma antibody levels, HCV antibody levels, demographic variables, and personality domains were estimated. Separate linear regressions were conducted using the standardized score for each personality domains as the dependent variable, with HCV antibody levels, TOX antibody levels, age, gender, and years of education as independent variables. The SPSS 22 software package was used to analyze the data.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

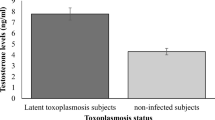

Among the participants (N = 255), the majority were men (86.3%). They were likely to be married (92.5%) and to be in full time paid employment (92.2%). Their ages ranged from 21 to 62 years, with a mean of 40.61 and SD 11.237. The duration of education ranged from 4 years to 20 years, with a mean of 12.76 and SD of 2.846. More than a third of the participants (36.5%) were machine operators and semiskilled workers, 39.6% were unskilled workers, and the remainder had administrative, executive, or other occupations. Based on the distribution of TOX antibody levels, seropositivity was defined as IgG level ˃ 2 units, and seropositivity was defined as HCV antibodies level ˃ 1 as specified by the manufacturer (Fig. 1). The prevalence of toxoplasma infection and HCV infection, based on seropositivity was 52.9% and 17.6%, respectively.

Initial analyses indicated significant positive correlations between HCV level and age (r = 0.439, P = 0.0001) and NEO agreeableness domain (r = 0.195, p = 0.002). There were significant negative correlations between HCV levels and education (r = − 0.185, p = 0.003) and NEO openness domain (r = -0.186, p = 0.003). No significant correlations were noted with Toxo levels (Table 2).

Regression analysis

Regression analyses were next conducted with NEO domains as the dependent variables, and the predictors are years of education, gender, toxoplasma level, HCV level, and age. No significant associations were noted between Toxo and HCV levels and any of the NEO domains (following corrections for multiple comparisons), though a nominally significant negative association between HCV levels and the “openness” domain was noted, consistent with the initial correlation analyses. A nominally significant association between age and neuroticism, as well as a highly significant association between gender and extraversion were also noted (Table 3). Similar patterns of associations were noted when seropositivity (based on cutoff values) was used instead of antibody levels.

Discussion

Toxo antibody levels were not significantly associated with scores on the NEO questionnaire after accounting for demographic variables, though univariate analyses indicated that HCV levels were positively correlated with “agreeableness” and negatively correlated with openness. These traits are more likely to be noted among “traditionalists,” i.e., individuals who rely on the values and beliefs of their family and heritage in seeking the best way for people to live and who believe that that following the established rules without questions is the best way to ensure peace and prosperity [42].

Our report differs from several studies, in which correlations with a variety of traits were reported (Table 1). Consistent and significant differences in Cattell’s personality factors were found between Toxoplasma infected and uninfected subjects in 9 of 11 studies, some of which reported that men infected with Toxo were more likely to disregard rules and were more expedient, suspicious, jealous, and dogmatic. Infected women, in contrast, showed higher warmth and higher superego strength (factors A and G on Cattell’s 16PF). There are several possible reasons for the differences between the published associations and the present negative report. The majority of the prior studies were conducted in European or US samples and were influenced by the type of residence (rural versus urban). Similar associations might not be detectable in other countries such as Egypt because of strain variation, because the patterns of Toxo effects are different, or because of cultural differences that impact the variations in personality traits [43]. Other differences between our study and the prior reports include having a small sample size. The associations are generally stronger among older individuals, suggesting that the effect size of the association is related to the duration of infection [44].

In a similar vein, we did not detect significant associations between HCV levels and personality traits using the NEO inventory, though several studies have reported on associations between HCV infection and personality traits [30,31,32] [33] as well as depressed mood [28, 45, 46].

Some limitations of the present study need to be considered. Men were over-represented in the sample, with predominantly employed and married individuals. Thus, the sample represents only one segment of the Egyptian population. In addition, it included relatively healthy individuals; thus, possible effects related to symptomatic infection with Toxo or HCV could not be investigated. As infection was identified on the basis of antibody levels in the serum, the precise timing or the duration of infection could not be estimated.

Conclusions

Toxo or HCV infections were not associated with variation in personality traits in a community-based sample of Egyptian adults. Further studies, including investigations of more severely infected individuals, as well as older individuals are indicated.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- DSM IV:

-

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

Fourth Edition

- HCV:

-

Hepatitis C virus

- IgG:

-

Immunoglobulin G

- NEO-FFI-3:

-

NEO personality inventory

- Toxo:

-

Toxoplasma gondii

References

Webster JP (2007) The effect of Toxoplasma gondii on animal behavior: playing cat and mouse. Schizophr Bull. 33(3):752–756

Webster JP, Gowtage-Sequeira S, Berdoy M, Hurd H (2000) Predation of beetles (Tenebrio molitor) infected with tapeworms (Hymenolepis diminuta): a note of caution for the manipulation hypothesis. Parasitology. 120(Pt 3):313–318 Epub 2000/04/12

Moore J, Gotteli NJ (1990) In: BJME BCJ (ed) Phylogenetic perspective on the evolution of altered host behaviours: a critical look at the manipulation hypothesis. Taylor and Francis

Hooshyar D, Hanson DL, Wolfe M, Selik RM, Buskin SE, McNaghten AD (2007) Trends in perimortal conditions and mortality rates among HIV-infected patients. AIDS 21(15):2093–2100

Nath A, Sinai AP (2003) Cerebral toxoplasmosis. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 5(1):3–12 Epub 2003/01/11

Flegr J, Klose J, Novotna M, Berenreitterova M, Havlicek J (2009) Increased incidence of traffic accidents in Toxoplasma-infected military drivers and protective effect RhD molecule revealed by a large-scale prospective cohort study. BMC Infectious Diseases 9:–72

Arling TA, Yolken RH, Lapidus M, Langenberg P, Dickerson FB, Zimmerman SA et al (2009) Toxoplasma gondii antibody titers and history of suicide attempts in patients with recurrent mood disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis. 197(12):905–908 Epub 2009/12/17

Flegr J (2013) Influence of latent Toxoplasma infection on human personality, physiology and morphology: pros and cons of the Toxoplasma-human model in studying the manipulation hypothesis. J Exp Biol. 216(Pt 1):127–133

Webster JP, Kaushik M, Bristow GC, McConkey GA (2013) Toxoplasma gondii infection, from predation to schizophrenia: can animal behaviour help us understand human behaviour? J Exp Biol. 216(Pt 1):99–112

Flegr J, Preiss M, Klose J, Havlicek J, Vitakova M, Kodym P (2003) Decreased level of psychobiological factor novelty seeking and lower intelligence in men latently infected with the protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii Dopamine, a missing link between schizophrenia and toxoplasmosis? Biol Psychol. 63(3):253–268 Epub 2003/07/11

Flegr J (2007) Effects of toxoplasma on human behavior. Schizophr Bull. 33(3):757–760 Epub 2007/01/16

Lindova J, Kubena AA, Sturcova H, Krivohlava R, Novotna M, Rubesova A et al (2010) Pattern of money allocation in experimental games supports the stress hypothesis of gender differences in Toxoplasma gondii-induced behavioural changes. Folia Parasitol (Praha) 57(2):136–142 Epub 2010/07/09

Manciuc C, Largu MA, Vâță A, Nicolau C, Prisăcariu LJ, Stoica D et al (2014) The impact of infectious diseases on personality traits - comparative study on HIV versus hepatitis B and C. BMC Infectious Diseases 14(Suppl 4):P15

Prandovszky E, Gaskell E, Martin H, Dubey JP, Webster JP, McConkey GA (2011) The neurotropic parasite Toxoplasma gondii increases dopamine metabolism. PLoS ONE 6(9):e23866 Epub 2011/10/01

Schwarcz R, Hunter CA (2007) Toxoplasma gondii and schizophrenia: linkage through astrocyte-derived kynurenic acid? Schizophr Bull. 33(3):652–653

Pearce BD, Kruszon-Moran D, Jones JL (2014) The association of Toxoplasma gondii infection with neurocognitive deficits in a population-based analysis. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology. 49(6):1001–1010

Adamo SA (2012) Parasites: evolution’s neurobiologists. J Exp Biol. 2013 216(Pt 1):3–10 Epub 2012/12/12

Lafferty KD (2005) Look what the cat dragged in: do parasites contribute to human cultural diversity? Behav Processes. 68(3):279–282 Epub 2005/03/29

Prasad KM, Watson AM, Dickerson FB, Yolken RH, Nimgaonkar VL (2012) Exposure to herpes simplex virus type 1 and cognitive impairments in individuals with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 38(6):1137–1148 Epub 2012/04/12

Nimgaonkar VL, Yolken RH, Wang T, Chang CC, McClain L, McDade E et al (2016) Temporal cognitive decline associated with exposure to infectious agents in a population-based, aging cohort. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 30(3):216–222 Epub 2015/12/29

Forton DM, Taylor-Robinson SD, Thomas HC (2006) Central nervous system changes in hepatitis C virus infection. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 18(4):333–338 Epub 2006/03/16

Forton DM, Thomas HC, Taylor-Robinson SD (2004) Central nervous system involvement in hepatitis C virus infection. Metab Brain Dis. 19(3-4):383–391

Forton DM, Allsop JM, Cox IJ, Hamilton G, Wesnes K, Thomas HC et al (2005) A review of cognitive impairment and cerebral metabolite abnormalities in patients with hepatitis C infection. AIDS 19(3):S53–S63

Kramer L, Bauer E, Funk G, Hofer H, Jessner W, Steindl-Munda P et al (2002) Subclinical impairment of brain function in chronic hepatitis C infection. J Hepatol. 37(3):349–354

Adair DM, Radkowski M, Jablonska J, Pawelczyk A, Wilkinson J, Rakela J et al (2005) Differential display analysis of gene expression in brains from hepatitis C-infected patients. AIDS 19(Suppl 3):S145–S150

Ibrahim I, Salah H, El Sayed H, Mansour H, Eissa A, Wood J et al (2016) Hepatitis C virus antibody titers associated with cognitive dysfunction in an asymptomatic community-based sample. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 38(8):861–868 Epub 2016/06/09

Erim Y, Tagay S, Beckmann M, Bein S, Cicinnati V, Beckebaum S et al (2010) Depression and protective factors of mental health in people with hepatitis C: a questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 47(3):342–349 Epub 2009/09/22

Dwight MM, Kowdley KV, Russo JE, Ciechanowski PS, Larson AM, Katon WJ (2000) Depression, fatigue, and functional disability in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Psychosom Res. 49(5):311–317

Golden J, O'Dwyer AM, Conroy RM (2005) Depression and anxiety in patients with hepatitis C: prevalence, detection rates and risk factors. General hospital psychiatry 27(6):431–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.06.006

Martinez-Raga J, Marshall EJ, Keaney F, Best D, Ball D, Strang J (2001) Hepatitis B and C in alcohol-dependent patients admitted to a UK alcohol inpatient treatment unit. Addiction biology. 6(4):363–372 Epub 2002/03/20

Yovtcheva SP, Rifai MA, Moles JK, Van Der Linden BJ (2001) Psychiatric comorbidity among hepatitis C-positive patients. Psychosomatics. 42(5):411–415

Batki SL, Canfield KM, Ploutz-Snyder R (2011) Psychiatric and substance use disorders among methadone maintenance patients with chronic hepatitisC infection: effects on eligibility for hepatitis C treatment. AmJAddict. 20:312–318

Marco A, Anton JJ, Trujols J, de la Hoya P S, de Juan J, Faraco I et al (2015a) Personality disorders do not affect treatment outcomes for chronic HCV infection in Spanish prisoners: the Perseo study. BMC Infectious Diseases. 15:355 Epub 2015/08/20

Marco A, Anton JJ, de la Hoya PS, de Juan J, Faraco I, Cayla JA et al (2015b) Personality disorders among Spanish prisoners starting hepatitis C treatment: prevalence and associated factors. Psychiatry Research. 230(3):749–756

Fabregas BC, Abreu MN, Dos Santos AK, Moura AS, Carmo RA, Teixeira AL (2014) Impulsiveness in chronic hepatitis C patients. General hospital psychiatry. 36(3):261–265

Bouratbine A, Aoun K (2014) Toxoplasmosis in the Middle East and North Africa. 2014:235–249

Mohamoud YA, Mumtaz GR, Riome S, Miller D, Abu-Raddad LJ (2013) The epidemiology of hepatitis C virus in Egypt: a systematic review and data synthesis. BMC Infectious diseases 13:288

Aboraya A, El-Missiry A, Barlowe J, John C, Ebrahimian A, Muvvala S et al (2014) The reliability of the standard for clinicians' interview in psychiatry (SCIP): a clinician-administered tool with categorical, dimensional and numeric output. Schizophr Res. 156(2-3):174–183 Epub 2014/05/21

Costa PJ, McCrae R (1989) Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI/NEO-FFI). Arabic Version by Arij Hanna, Baghdad university, Department of Psychology. Reproduced by special permission of the publisher, Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc., 1624 North Florida Ave, Lutz, Florida 33549. 1989

Hassan J, McDonnell V, Crean M, Connell J (2013) Comparative evaluation of three commercial automated immunoassays: Architect (Abbott), Vidas® (BioMérieux) and LIAISON® XL (Diasorin), for the Detection of Antibody to Hepatitis C Virus. . Global Journal of Immunology and Allergic Diseases. 2013;1:60–4

Dickerson F, Stallings C, Origoni A, Vaughan C, Katsafanas E, Khushalani S et al (2014) Antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii in individuals with mania. Bipolar Disord. 16(2):129–136

Coasta PT, McCrae RR (1992) Normal personality assessment in clinical practice: the NEO personality inventory. Psychological assessment. 4(1):5–13

Hashism MT, Al-Kaseer E, Al-Diwan JK, Abdul Aziz NS, Hassan MA (2011) Personality and mood profile of women with toxoplasmosis. The Iraqi Postgraduate Medical Journal 2011, 10(2)

Flegr J, Guenter W, Bieliński M, Deptuła A, Zalas-Więcek P, Piskunowicz M et al (2012) Toxoplasma gondii infection affects cognitive function – corrigendum.pdf. Folia Parasitologica 59(4):253–254

Goulding C, O'Connell P, Murray FE (2001) Prevalence of fibromyalgia, anxiety and depression in chronic hepatitis C virus infection: relationship to RT-PCR status and mode of acquisition. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 13(5):507–511 Epub 2001/06/09

Lehman CL, Cheung RC (2002) Depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress, and alcohol-related problems among veterans with chronic hepatitis C. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 97(10):2640–2646

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: preparation of this manuscript was supported part by grants from the Stanley Medical Research Institute (07R-1712 and 11 T-06) and from the National Institutes of Health (MH093246, D43 TW009114, MH63480, D43TW008302).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

II helped in the design, interviewing the subjects, and writing the manuscript.

ST helped in the design of the study and writing of the manuscript.

HS helped in interviewing the subjects.

HE helped in interviewing the subjects.

HM helped in the design of the study and in writing the manuscript.

AE helped in interviewing the subjects.

JW helped in the data analysis.

WF helped in interviewing the subjects.

FD helped in the design of the study and in writing the manuscript.

RY helped in the design of the study and in writing the manuscript.

WE helped in the design of the study and in writing the manuscript.

VN helped in the design of the study and in writing manuscript.

The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee at Mansoura University and the Institutional Review Board at the University of Pittsburgh.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ibrahim, I.M.A., Tobar, S., Salah, H. et al. Failure to replicate associations between Toxoplasma gondii or hepatitis C virus infection and personality traits. Middle East Curr Psychiatry 29, 17 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43045-021-00169-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43045-021-00169-7