Abstract

Background

Vitamin D is involved in many brain processes including neurological immune process, regulation of neurological factors, and neuroplasticity. Some studies have linked low serum vitamin D to major depressive disorder (MDD) and schizophrenia, while others have not shown any relationship. The study aimed to assess vitamin D level in patients with depression and those with schizophrenia. Sixty participants were recruited from outpatient clinics of the Institute of Psychiatry, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt. The sample was divided into three groups: group A, 20 patients with MDD; group B, 20 patients with schizophrenia, and group C, 20 healthy control subjects. Ain Shams Psychiatry Clinical Interview was used to gather demographic data, and Structured Clinical interview (SCID-I) and laboratory vitamin D serum levels (ELISA) were applied to subjects.

Results

Eighty-five percent of patients with MDD and 80% of patients with schizophrenia had below normal vitamin D serum level. Compared to controls, vitamin D serum concentration in patients with MDD was statistically significantly lower than controls, while schizophrenia had vitamin D level lower than did control group but higher level than patients with MDD. However, vitamin D level failed to differentiate between patients diagnosed with schizophrenia and those with MDD.

Conclusions

Patients with MDD and those with schizophrenia demonstrated lower vitamin D level compared with health controls. There was no statistically significant difference in vitamin D level between patients with MDD and those with schizophrenia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Vitamin D is a unique neurosteroid hormone that may have an important role in the development of psychiatric diseases [1]. While vitamin D insufficiency (serum level of 10 to 30 ng/ml) shows no overt clinical symptoms [2], frank vitamin D deficiency (serum level below 10 ng/ml) has long been recognized as a medical condition characterized by muscle weakness, impaired bone mineralization, bone pain, and fractures [3, 4]. Recent research has established the important role of vitamin D in mineral balance and proper immune system functioning [5], as well as in the pathogenesis of various diseases, including cancer and autoimmune disorders [6, 7].

The association of vitamin D with psychiatric disorders, however, is less clear. In fact, vitamin D receptor is widely expressed in human brain [1] and has been reported to regulate multiple neurotransmission pathways, including dopamine, serotonin, noradrenalin, and glutamine [8]. Therefore, it is not surprising that low vitamin D concentrations is linked to several psychiatric conditions, such as autistic spectrum disorder [9], attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, depression, and schizophrenia [10, 11].

In addition, several studies showed that vitamin D was important for cognitive functions [12], especially in elderly [13] or Alzheimer disease [14].

There are several postulated mechanisms for vitamin D impact on the brain. First, vitamin D regulates numerous brain processes including neurotrophic factors, neuroimmunomodulation, neuroprotection, neuroplasticity, and brain development [15]. This association is strengthened by the preclinical data indicating vitamin D deficiency in early life affects neuronal differentiation, axonal connectivity, and brain structure and function [16, 17]. In the same line, another study showed vitamin D deficiency during infancy to act as vulnerability factor for schizophrenia [18].

Second, vitamin D regulates calcium signaling and reduces neurotoxic calcium levels in the brain [19, 20].

Third, other studies have also shown that vitamin D is linked to tyrosine hydroxylase and tryptophan hydroxylase—the rate-limiting enzymes in the biosynthesis of dopamine and serotonin, respectively [21]—linking vitamin D deficiency and depression [22, 23].

Fourth, altered dopamine transporter expression, neonatal catechol-O-methyl transferase expression, and dopamine metabolism were also reported, linking vitamin D to schizophrenia [8].

Depression and schizophrenia, the focus of this research, are psychiatric disorders with a complex and multifactorial pathophysiology [24, 25]. Both conditions are chronic and are both considered the top leading causes of disability worldwide [26, 27].

The association between vitamin D and depression is controversial, with some studies supporting this [28,29,30,31], while others have shown no relationship [32].

In the young adults, depression was linked to vitamin D deficiency [33,34,35], as well as in the elderly [36]. A recent study showed vitamin D-deficient individuals to have 3.5 higher odds of developing depression in comparison to those with sufficient vitamin D [37].

Likewise, the link between vitamin D deficiency and the development of schizophrenia has been long investigated. There is preliminary evidence linking vitamin D insufficiency to risk of isolated psychotic symptoms [38]. Neonatal vitamin D deficiency was associated with a significantly increased risk of schizophrenia [18, 39]. One meta-analysis found that vitamin D-deficient participants were 2.16 times more likely to have schizophrenia than vitamin D-sufficient participants [40].

Although there is much information on vitamin D deficiency in patients with MDD and schizophrenia, few studies compared such deficiencies in patients with these disorders, particularly in an Egyptian population.

We hypothesized that vitamin D levels in patients diagnosed with depression and schizophrenia are lower than controls and that certain cut-off points could predict a certain psychiatric diagnosis (i.e., depression vs. schizophrenia). The aim of this study was to investigate the serum level of vitamin D in an Egyptian sample of patients diagnosed with MDD and schizophrenia, compared with healthy controls.

Methods

Study design and participants

This was a cross-sectional, comparative study. It was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Psychiatry, Ain Shams University. A convenient sample of patients diagnosed with MDD and schizophrenia was selected from the outpatient clinics of Ain Shams University, Psychiatry Department, Cairo, Egypt, which was held on a daily basis in the period between January 2018 and January 2019. The Institute of Psychiatry is located in Eastern Cairo and serves a catchments area of about the third of Greater Cairo. It serves both urban and rural areas.

The study included a statistically significant number of (40) patients: 20 with major depressive disorder (MDD) and 20 with schizophrenia.

Inclusion criteria

From January 2018 until January 2019, male and female patients aged between 20 and 50 years, fulfilling the diagnoses of MDD or schizophrenia, as outlined in the DSM-IV criteria, and agreed to participate in the study were included.

Twenty apparently healthy volunteers were included as a control group; having no history of psychiatric diseases, medical diseases and not receiving any medications that may affect vitamin D level. They were matched for age, gender, and social standard to the case groups.

Exclusion criteria

Subjects were excluded from the study if they had any of the following conditions: past history of psychiatric disorders other than MDD or schizophrenia, pregnant females, and patients with medical conditions that might affect vitamin D levels like the liver, kidney, malabsorption diseases (which are revealed and excluded by history taking and examination if needed), and those who refused to sign consent.

Procedure

All eligible subjects were assessed using the following tools. The interviews were conducted in a quiet, comfortable setting, and each interview lasted about 1 h.

Tools

-

1.

A pre-formed complete history data sheet (Ain Shams psychiatry clinical interview) was used to record demographic information and clinical history of the participants. Also, an assessment of concurrent medical conditions, concomitant therapies was done.

-

2.

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorder (SCID-I):

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID I) [41]. Arabic version was used [42].

This was used for diagnosis of MDD or schizophrenia and exclusion of any comorbid psychiatric disorder. It is a clinician-administered semi-structured interview. It provides broad coverage of psychiatric axis I diagnosis according to DSM IV, and it consists of nine diagnostic modules (mood episode, psychotic symptom, psychotic disorder differential, mood disorder differential, substance use, anxiety, somatoform disorder, eating disorder, and adjustment disorder).

-

3.

ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay)

This test kit is a competitive protein binding assay for the measurement of 25–OH vit D. It is based on the competition of 25–OH vit D present in the sample with 25–OH vit D tracer, for the binding pocket of vitamin D binding protein (VDBP, Gc-globulin).

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis was done on a personal computer using IBM SPSS statistics (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) software version 18.0, IBM Corp., Chicago, USA, 2009.

Inferential analyses were done for quantitative variables using Shapiro-Wilk test for normality testing, independent t test in cases of two independent groups with normally distributed data and ANOVA test with post hoc Bonferroni test for more than two independent groups with normally distributed data. In qualitative data, inferential analyses for independent variables were done using chi-square test for differences between proportions and Fisher’s exact test for variables with small expected numbers with post hoc Bonferroni test. While correlations were done using Pearson correlation for numerical normally distributed data. Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was used to examine the value of numerical variables for prediction of dichotomous outcomes. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was estimated, and the best cut-off criterion was defined as that associated with the highest Youden index (J), where J = (sensitivity + specificity) – 1.

Results

This study is a cross-sectional case-control study. During the study period, 66 met the eligibility criteria for the study: 3 patients refused to sign the consent, and 3 patients dropped out.

Demographic and clinical data of the study participants

The means of age of both groups of MDD and schizophrenia patients were 28 years ± 7 and 31 years ± 8, respectively and that of controls to be 28 years ± 2, with almost half of patients to be males and half females in all three groups. No statistically significant differences were found between all 3 groups regarding age or gender.

There was no statistically significant difference between patients’ groups according to age of onset or pharmacotherapy treatment modality. However, the schizophrenia group had longer duration of illness and higher number of episodes compared to the MDD group (Table 1).

Comparison between study groups with regard to vitamin D serum level and severity of hypovitaminosis D

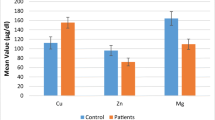

Both groups of patients showed lower levels of serum vitamin D level when compared with healthy controls; this was highly statistically significant. The group with MDD had lower levels of vitamin D when compared with the schizophrenia group (Table 2), Fig. 1.

Demographic and clinical variables associated with low serum vitamin D among the study sample

In both groups with MDD and schizophrenia, there was no statistically significant association between vitamin D serum level and the patients’ age, age of onset, or duration of illness or the number of previous episodes.

In addition, vitamin D serum level was lower in female patients than in males, yet with no statistically significant difference (Table 3).

Diagnostic performance and characteristics of vitamin D in differentiating between study groups

The current study used (receiver-operating characteristic) ROC curve analysis to compare the diagnostic performance of vitamin D among patients with MDD and schizophrenia in comparison to healthy participants.

Diagnostic performance of vitamin D in differentiation between the study groups

The current results showed that vitamin D serum level—with a cut-off value of ≤ 14 ng/ml—had significantly moderate diagnostic performance in differentiating patients MDD from control group and significantly low diagnostic performance in differentiating patients with schizophrenia from control group.

In addition, there was non-significant diagnostic performance for vitamin D level in differentiating MDD group from schizophrenia group (Table 4, Fig. 2).

Diagnostic characteristics of vitamin D level in differentiating between groups

Vitamin D ≤ 14 ng/ml had excellent specificity, but low in other diagnostic characteristics in differentiating patients with MDD group from the control group.

Vitamin D ≤ 14 ng/ml has excellent specificity, but low in other diagnostic characteristics in differentiating patients with schizophrenia group from control group.

Discussion

The understanding of the basic physiology of vitamin D functions in the brain is steadily increasing. Studies suggest an association between low levels of vitamin D and the expression of MDD as well as schizophrenia [37, 40]. However, the questions—whether there is a certain cut-off point that could predict the risk for psychiatric disorders, and if vitamin D level is disease specific—are still not answered yet.

Vitamin D status in the patient groups and healthy controls

During the assessment of the current sample, we found vitamin D serum level to be highly significantly lower in patients with MDD compared to controls, where 75% of the MDD patients had vitamin D deficiency/severe deficiency.

In agreement with our results, two studies found that more than half of their samples of depressed patients had low vitamin D levels [32, 37, 43,44,45]. Other studies had equivocal results [44, 46]. For example, one study found no difference in serum vitamin D level between depression and healthy controls [47], which could be attributed to different study design; while we used standardized tool for psychiatric diagnoses, they used register-based diagnoses.

The pathology underlying vitamin D association with depression is a multifactorial one. One psychological proposition suggests that depression is associated with behavioral withdrawal, which would typically reduce outdoor activities and therefore sun exposure potentially leading to vitamin D deficiency [48]. Alternatively, the somatic effects of vitamin D deficiency (fatigue, vague aches) might contribute to a general lowering of mood, which could be viewed as the “psychologization” of somatic symptoms [48].

Additionally, the identification of vitamin D receptors on neurons and glia in various regions of the brain (e.g., hippocampus, cingulate cortex), further support speculations about vitamin D’s relationships with neurotransmitters and psychopathological processes underlying depression [1].

In schizophrenia group, results showed their vitamin D serum level to be statistically significantly lower compared with controls with 55% of the schizophrenia patients had vitamin D deficiency/severe deficiency.

Many studies came in line with our results, linking hypovitaminosis D to psychosis [16, 49,50,51,52,53,54], especially during acute exacerbation of psychotic episodes [55]. Studies also found lower vitamin D levels among schizophrenia patients as compared with those in healthy controls [40, 55,56,57]. However, other research failed to reproduce these findings [58]. For example, in a recent study, although serum vitamin D tended to be lower in the group with schizophrenia than in the control group, this difference did not reach statistical significance. However, this study used a non-clinical sample drawn from the general population, which is more likely to have less severity of psychotic symptoms [47].

In agreement with our results, two studies showed that nearly 65% of patients with schizophrenia had vitamin D deficiency [40, 59].

However, in contrast, a study concluded that the odds of schizophrenia were not different for insufficient versus sufficient subjects [60]. Yet, this study included different ethnic groups, which may have caused this study to give different results from ours.

Like depression, schizophrenia patients are less likely to adopt a healthy lifestyle, with unhealthy dietary patterns which increases the risk for inadequate vitamin D intake. Moreover, they tend to be more sedentary and physically less active than general population, which predisposes them to inadequate ultraviolet-B radiation for vitamin D synthesis [61].

Vitamin D status in the depression group vs. schizophrenia group

The current study showed that patients with schizophrenia had a lower level of vitamin D level when compared with healthy controls; yet, a higher level when compared to patients with MDD. This result is worth noting given that patients with schizophrenia had longer duration of illness and higher number of episodes compared to the MDD group.

Studies comparing vitamin D level between patients with MDD and schizophrenia are scarce. Contrary to our results, a study has concluded that serum vitamin D levels were lower in patients with schizophrenia compared to patients with MDD and to healthy controls [57]. In another study, no differences were found in vitamin D level between schizophrenia and non-psychotic depression [47]. This finding warrants further investigation and needs to be replicated on a wider scale to be confirmed.

Association of low vitamin D levels with demographic and clinical characteristics of the study groups

Results showed that none of the patients’ demographic or clinical variables (the age of presentation, age of onset, duration of illness or the number of previous episodes) were found to be associated with low level of serum vitamin D.

However, the current study revealed that vitamin D serum level was higher in men than in their female counterparts with MDD, schizophrenia, and even controls; yet, it did not reach statistical significance, which may not be detected due to small sample size. These results should be analyzed with caution due to involvement of other cultural and religious factors. For example, the Islamic uniform covering most of the female’ bodies may interfere with their exposure to sunlight which is essential for vitamin D synthesis. This needs further evaluations in future studies.

Like our study, a cohort study found that only women, not men, with low vitamin D levels had significantly higher risk of developing depressed mood during 6 years of follow-up [45]. And it agrees with reports of high rates of vitamin D deficiency in women in general [33].

It is worth noting that the lack of correlation with any of the demographic or clinical variables may indicate that hypovitaminosis D may be a comorbidity rather than a cause or a complication to these diseases. This observation warrants further future investigation.

Diagnostic performance of vitamin D in MDD and schizophrenia

We found that patients with hypovitaminosis D (< 14 ng/ml) are most likely to have MDD or schizophrenia; yet, it cannot be used as a diagnostic test as multiple trials needed to confirm its diagnostic value.

A recent study showed that vitamin D deficiency was an independent predictor for the presence of depression even after adjustment for multiple confounding factors in patients [62].

Another study showed that among women, there was an elevated risk for depression over a broader range of vitamin D deficiency of less or equal to 20 ng/ml in women. For men, however, an elevated risk for depression was true only for a deficiency of lower than 12 ng/ml [63].

In addition, there was non-significant diagnostic performance for vitamin D level in differentiating MDD group from schizophrenia group. Some studies agreed that vitamin D concentration did not differ between schizophrenia or depression [47, 64].

Yet, there is little published evidence directly connecting vitamin D diagnostic value in patients with MDD or schizophrenia.

The contribution of vitamin deficiencies to these processes is not fully understood. Vitamin D deficiency may set the stage for both the onset and the progression of MDD and/or schizophrenia by acting synergistically with other factors as genetics and environmental stressors [21]. Potential aggravation of these processes due to vitamin deficiencies should not be overlooked. Therefore, patient groups at risk for specific vitamin deficiencies should be identified to implement timely and appropriate interventions.

The present study has several limitations; the small sample size and non-random method of sampling suggest that it may not be representative of all patients with MDD or schizophrenia in Egypt. In addition, the cross-sectional nature of the study limits our ability to draw causal inferences. Longitudinal studies are required to determine whether hypovitaminosis D is the cause or the effect. Despite these limitations, the current findings are important in clarifying the relation between MDD, schizophrenia, and vitamin D, which will provide guidance for future research. Moreover, it is one of the few studies to compare between vitamin D level in MDD and schizophrenia.

Conclusions

The present study showed patients diagnosed with depression and schizophrenia to have a statistically significant lower level of vitamin D compared to healthy controls. However, the level of vitamin D failed to differentiate between patients with depression and those with schizophrenia.

Availability of data and materials

All data and materials are available for revision.

Abbreviations

- MDD:

-

Major depressive disorder

- SCID I:

-

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- VDBP:

-

Vitamin D binding protein

- ROC:

-

Receiver-operating characteristic

References

Eyles DW, Smith S, Kinobe R et al (2005) Distribution of the vitamin D receptor and 1 alpha-hydroxylase in human brain. J chem neuroanat 29(1):21–30

DeLuca HF (2004) Overview of general physiologic features and functions of vitamin D. Am J Clin Nutr 80:1689–1696

Al-oanzi ZH, Tuck SP, Raj N et al (2006) Assessment of vitamin D status in male osteoporosis. Clin chem 52:248–254

Bell TD, Demay MB, Burnett-Bowie SAM. The biology and pathology of vitamin D control in bone. J Cell Biochem 2010; 111(1): 7–13.

Martineau AR, Wilkinson KA, Newton SM et al (2007) IFN-gamma- and TNF-independent vitamin D-inducible human suppression of mycobacteria: the role of cathelicidin LL-37. J Immunol 178(11):7190–7198

Balion C, Griffith LE, Strifler L et al (2012) Vitamin D, cognition, and dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology 79:1397–1405

Munger KL, Levin LI, Hollis BW et al (2006) Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and risk of multiple sclerosis. JAMA 296(23):2832–2838

Kesby JP, Turner KM, Alexander S et al (2017) Developmental vitamin D deficiency alters multiple neurotransmitter systems in the neonatal rat brain. Int J Dev Neurosci 62:1–7

Cannell JJ, Hollis BW (2008) Use of Vitamin D in Clinical Practice. Altern Med Rev 13(1):6–20

Groves NJ, McGrath JJ, Burne TH (2014) Vitamin D as a neurosteroid affecting the developing and adult brain. Annu Rev Nutr 34:117–141

Sharif MR, Madani M, Tabatabaei F et al (2015) The relationship between serum vitamin D levels and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Iran J Child Neurol 9(4):48–53

Laughlin GA, Kritz-Silverstein D, Bergstrom J et al (2017) Vitamin D insufficiency and cognitive function trajectories in older adults: the rancho bernardo study. J Alzheimers Dis 58:871–883

Slinin Y, Paudel M, Taylor BC et al (2012) Association between serum 25(OH) vitamin D and the risk of cognitive decline in older women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 67(10):1092–1098

Annweiler C, Llewellyn DJ, Beauchet O (2013) Low serum vitamin D concentrations in Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Alzheimers Dis 33:659–674

Fernandes de Abreu DA, Eyles D, Eyles D, et al. Vitamin D, a neuroimmunomodulator: implications for neurodegenerative and autoimmune diseases. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2009; 34 (1): 265–277.

Eyles DW, Burne TH, McGrath JJ (2013) Vitamin D, effects on brain development, adult brain function and the links between low levels of vitamin D and neuropsychiatric disease. Front Neuroendocrinol 34:47–64

Yates NJ, Tesic D, Feindel KW et al (2018) Vitamin D is crucial for maternal care and offspring social behaviour in rats. The Journal of endocrinology 237:73–85

McGrath JJ, Eyles DW, Pedersen CB et al (2010) Neonatal vitamin D status and risk of schizophrenia: a population-based case-control study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 67(9):889–894

Berridge MJ (2015) Vitamin D: a custodian of cell signalling stability in health and disease. Biochem Soc Trans 43:349–358

Kalueff AV, Eremin KO, Tuohimaa P (2004) Mechanisms of neuroprotective action of vitamin D 3. Biochem (Mosc) 69(7):738–741

Cui X, Pertile R, Liu P et al (2015) Vitamin D regulates tyrosine hydroxylase expression: n-cadherin a possible mediator. J Neurosci 304:90–100

Kaneko I, Sabir MS, Dussik CM et al (2015) 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D regulates expression of the tryptophan hydroxylase 2 and leptin genes: implication for behavioral influences of vitamin D. FASEB 29:4023–4035

Patrick RP, Ames BN (2015) Vitamin D and the omega-3 fatty acids control serotonin synthesis and action, part 2: relevance for ADHD, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and impulsive behaviour. FASEB 29:2207–2222

Blazer DG (2003) Depression in late life: review and commentary. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 58:249–265

Krishnan V, Nestler EJ (2010) Linking molecules to mood: new insight into the biology of depression. Am J Psychiatry 167:1305–1320

Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M et al (2006) Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet 367:1747–1757

World Health Organization. 2011. http://www.who.int/mental_health/management/depression/definition/en/

May HT, Bair TL, Lappe DL et al (2010) Association of vitamin D levels with incident depression among a general cardiovascular population. Am Heart J 159:1037–1043

Moy FM, Hoe VC, Hairi NN et al (2017) Vitamin D deficiency and depression among women from an urban community in a tropical country. Public health nutr 20(10):1844–1850

Parker G, Brotchie H (2011) Mood effects of the amino acids tryptophan and tyrosine. Acta Psychiatr Scand 124(6):417–426

Vidgren M, Virtanen JK, Tolmunen T et al (2018) Serum concentrations of 25 Hydroxyvitamin D and depression in a general middle-aged to elderly population in Finland. J Nutr Health Aging 22(1):159–164

Chan R, Chan D, Woo J et al (2011) Association between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and psychological health in older Chinese men in a cohort study. JAD 130:251–259

Kerr DCR, Zava DT, Piper WT et al (2015) Associations between vitamin D levels and depressive symptoms in healthy young adult women. Psychiatry Res 227(1):46–51

Okereke OI, Singh A (2016) The role of vitamin D in the prevention of late-life depression. JAD 198:1–14

Polak MA, Houghton LA, Reeder AI et al (2014) Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations and depressive symptoms among young adult men and women. Nutrients 6:4720–4730

Hoogendijk WJG, Lips P, Dik MG et al (2008) Depression is associated with decreased 25-hy-droxyvitamin D and increased parathyroid hormone levels in older adults. Arch Gen psychiatry 65:508–512

Sherchand O, Sapkota N, Khan SA et al (2018) Association between vitamin D deficiency and depression in Nepalese population. Psychiatry Res 267:266–271

Hedelin M, Lof M, Olsson M et al (2010) Dietary intake of fish, omega-3, omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids and vitamin D and the prevalence of psychotic like symptoms in a cohort of 33 000 women from the general population. BMC Psychiatry 10:38

Eyles DW, Trzaskowski M, Vinkhuyzen AA et al (2018) The association between neonatal vitamin D status and risk of schizophrenia. Sci Rep 8(1):17692

Valipour G, Saneei P, Esmaillzadeh A (2014) Serum vitamin D levels in relation to schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 99(10):3863–3872

First MB, Spitzer RL, Williams W et al (1995) Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders (SCID-I) in Handbook of Psychiatric Measures. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC

Missiry A, Sorour A, Sadek A et al (2004) Homicide and psychiatric illness: an Egyptian Study (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt, Faculty of Medicine

Wilkins CH, Sheline YI, Roe CM et al (2006) Vitamin D deficiency is associated with low mood and worse cognitive performance in older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 14(12):1032–1040

Anglin RE, Samaan Z, Walter SD et al (2013) Vitamin D deficiency and depression in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J psychiatry 202:100–107

Milaneschi Y, Shardell M, Corsi AM et al (2010) Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and depressive symptoms in older women and men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:3225–3233

Almeida OP, Hankey GJ, Yeap BB (2015) (2015). Vitamin D concentration and its association with past, current and future depression in older men. The Health in Men Studies Maturitas 81:36–41

Ikonena H, Palaniswamy S, Nordstrom T, et al. Vitamin D status and correlates of low vitamin D in schizophrenia, other psychoses and non-psychotic depression–The Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1966 study. Psychiatry Res 2019; 279: 186-194.

Thomas J, Al-Anouti F (2018) Sun exposure and behavioral activation for hypovitaminosis d and depression: a controlled pilot study. Community Ment Health J 54:860–865

Belvederi M, Respino M, Masotti M et al (2013) Vitamin D and psychosis: mini meta-analysis. Schizophr Res 150:235–239

Berg AO, Melle I, Torjesen PA et al (2010) A cross-sectional study of vitamin D deficiency among immigrants and Norwegians with psychosis compared to the general population. J clin psychiat 71(12):1598–1604

Brown AS (2011) The environment and susceptibility to schizophrenia. Prog Neurobiol 93:23–58

Gracious BL, Finucane TL, Friedman-Campbell M et al (2012) Vitamin D deficiency and psychotic features in mentally ill adolescents: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 12:38

Haddad C, Zoghbi M, Hallit S et al (2017) Vitamin D Levels in Lebanese Patients with Schizophrenia: A Case-Control Study. Ann Nutr Disord & Ther 4(1):1041

Yazici AB, Ciner O, Yazici E et al (2019) Comparison of vitamin B12, vitamin D and folic acid blood levels in patients with schizophrenia, drug addiction and controls. J Clin Neurosci 65:11–16

Yüksel RN, Altunsoy N, Tikir B et al (2014) Correlation between total vitamin D levels and psychotic psychopathology in patients with schizophrenia: therapeutic implications for add-on vitamin D augmentation. Ther Adv Psychopharm 4(6):268–275

Crews M, Lally J, Gardner-Sood P et al (2013) Vitamin D deficiency in first episode psychosis: a case-control study. Schizophr Res 150:533–537

Itzhaky D, Amital D, Gorden K et al (2012) Low serum vitamin D concentrations in patients with schizophrenia. Isr Med Assoc J 14(2):88–92

Graham KA, Keefe RS, Lieberman JA et al (2015) Relationship of low vitamin D status with positive, negative and cognitive symptom domains in people with first-episode schizophrenia. Early interv psychia 9:397–405

Ristic S, Zivanovic S, Milovanovic DR et al (2017) Vitamin D deficiency and associated factors in patients with mental disorders treated in routine practice. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol 63(2):85–95

Clelland JD, Read LL, Drouet V et al (2014) Vitamin D insufficiency and schizophrenia risk: evaluation of hyperprolinemia as a mediator of association. Schizophr Res 156(1):15–22

Hahn LA, Mackinnon A, Foley DL et al (2018) Counting up the risks: how common are risk factors for morbidity and mortality in young people with psychosis? Early Interv Psychiatry 12(6):1045–1051

Jhee JH, Kim H, Park S et al (2017) Vitamin D deficiency is significantly associated with depression in patients with chronic kidney disease. PLoS ONE 12(2):e0171009

De Oliveira C, Hirani V, Biddulph JP (2017) Associations between vitamin D levels and depressive symptoms in later life: evidence from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA). J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 73(10):1377–1382

Schneider B, Weber B, Frensch A et al (2000) Vitamin D in schizophrenia, major depression and alcoholism. J Neural Transm 107:839–842

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.O. contributed to the study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, and critical revision of the manuscript. W.S. contributed to the study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data. M.H. made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the present study and data interpretation. M.A. contributed to the interpretation of results and writing and editing the manuscript. A.M.A. recruited and studied the patients and gathered all data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The nature and scope of the study were discussed with each patient, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients. The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Research and Ethics Committee of the Institute of Psychiatry, Ain Shams University. The committee’s reference number is not available.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Okasha, T.A., Sabry, W.M., Hashim, M.A. et al. Vitamin D serum level in major depressive disorder and schizophrenia. Middle East Curr Psychiatry 27, 34 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43045-020-00043-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43045-020-00043-y