Abstract

Background

Familial Mediterranean fever (FMF), known as a disease with a high prevalence rate among Armenian, Turkish, Jewish, and Arab descent populations, occurs as a result of pathogenic variants in mediterranean fever (MEFV) gene. The aim of this study was to review the spectrum and frequency of MEFV gene mutations reported among Iranian FMF patients.

Methods

After performing a systematic review of the literature and implementation of inclusion and exclusion criteria, 16 articles published between 2004 and 2020, involving 4,256 Iranian FMF patients, were included.

Results

A total of 38 different MEFV gene mutations were identified. The most common mutations among Iranian FMF patients were: p.M694V (c.2080A > G) (20.27%), p.E148Q (c.442G > C) (10.27%), p.V726A (c.2177T > C) (8.24%), p.M680I (both c.2040G > C and c.2040G > A) (7.20%), p.R761H (c.2282G > A) (2.1%), and p.M694I (c.2082G > A) (2. 1%). The frequencies of these mutations were significantly different in different parts of the country.

Conclusions

The ranks and frequencies of p.M694V, p.E148Q, p.V726A, p.M680I, and p.M694I in our population were closer to those observed in the Mediterranean countries, especially in the Middle Eastern Arab populations. Although some comprehensive studies have been performed on Azeri Turkish patients living in northwestern Iran, studies in other areas, especially in eastern Iran, have been very limited. One reason for this observation could be due to the low frequency of FMF patients in those areas. Regardless of the reason for this, the exact spectrum and frequency of MEFV gene mutations in Iranian FMF patients remain unclear. Therefore, comprehensive future studies in different parts of the country are recommended.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

As the most common form of monogenic autoinflammatory diseases [1], familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) has been known as a disease with a high prevalence rate among Armenian, Turkish, Jewish, and Arab descent populations [2]. This disease is characterized by recurrent fever and serositis (e.g., peritonitis, pleuritis, synovitis) symptoms [1, 3]. Most of FMF patients experience the first attacks before the age of 20, with a mean age of onset between 3 and 9 years. However, the disease is not unlikely to occur after the age of 40 [1].

Although FMF has typically been described as an autosomal recessive inherited disease, there are rare studies that support the autosomal dominant pattern of the disease [4,5,6]. FMF disease occurs as a result of pathogenic variants in Mediterranean fever (MEFV) gene. This gene is located on the short arm of chromosome 16 (16p13.3), consists of ten exons and encodes a 781-amino acid protein called pyrin [1, 7]. The Infevers database (https://infevers.umai-montpellier.fr/web/) is an online databank for mutations that play a role in autoinflammatory diseases. The current total number of MEFV gene sequence variants in this database is 384, most of which are found in exons 2, 10, 3, 5, and 1, respectively. In addition, more than 96% of the mutations are classified as substitutions.

Only a limited number of MEFV gene mutations are common; the others are rare mutations with no clinical phenotypes and are mainly observed in populations where FMF is not prevalent [7]. Although the mutations of p.M694V (c.2080A > G), p.M680I (c.2040G > C), p.V726A (c.2177T > C), p.M694I (c.2082G > A), and p.E148Q (c.442G > C) have been observed in more than two thirds of FMF cases in at risk populations, their frequencies may differ between ethnic groups [1].

Iran is a country with a mixture of different ethnicities including Persians, Azeri Turks, Kurds, Arabs, Lurs, Gilaks, and so on. There is no comprehensive data on the prevalence of FMF disease in the Iranian population. However, based on published studies, the focus of the disease seems to be among Azeri Turks living in the northwest. In this study, the spectrum and frequency of MEFV gene mutations previously reported among Iranian FMF patients have been reviewed.

Methods

Search strategy

Using the keywords of Familial Mediterranean Fever, FMF, MEFV, and Iran, as well as their Persian equivalents, in all possible combinations, a comprehensive search was performed on the online databases of Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed, ProQuest, Cochrane, Science Direct, Magiran, and SID. An example of a combined search in the PubMed database is as follows: (((Familial Mediterranean Fever[Title/Abstract]) OR (FMF[Title/Abstract])) AND (MEFV[Title/Abstract])) AND (Iran[Title/Abstract]). No time or language limitations were considered. To maximize the comprehensiveness of the search, references used in all associated articles were manually reviewed.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: all studies investigated the spectrum of MEFV gene mutations in Iranian FMF patients, with sufficient data and full text availability. The exclusion criteria were non-Iranian, review, duplicate, irrelevant, and conference studies.

Study selection

The extracted articles were reviewed independently by two investigators. If they did not agree on a particular article, it was discussed by all authors. Three steps including the exclusion of duplicated articles, the exclusion of irrelevant articles based on the title and abstract, and the exclusion of irrelevant articles based on the full text of the articles were our process in selecting articles.

Quality evaluation

The quality of the studies was evaluated using the Strengthening of the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist. The checklist consists of 32 sections that cover different parts of a report. Considering the threshold score of 16, articles with this score or higher were selected and the remainder were excluded from the study.

Data extraction

A checklist was used to extract the required information including article title, first author’s name, year of publication, region/province, sample size (total, males, and females), mean age of disease onset, mutation detection rate, the rate of consanguineous marriages, and patients' clinical symptoms from each article.

The gene reference sequence was NG_007871.1. NM_000243.2 was used to determine the variant position. Position of the variants in protein was determined based on UniProtKB/SwissProt O15553-2.

Results

Using the PRISMA guidelines, a systematic review on the mutation spectrum of the MEFV gene in Iranian FMF patients was carried out and a total of 444 articles were found. Following the exclusion of 428 articles due to duplication and irrelevant to our subject, 16 articles published between 2004 and 2020, involving 4,256 Iranian FMF patients, were included in this systematic review. Nine studies were performed on patients from different regions [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16], six studies were performed on Azeri Turkish patients living in the northwest [17,18,19,20,21,22], and one study was performed in the southwest of Iran [23] (Table 1). The ratio of male to female varied from 0.57 to 1.68. The mean age of disease onset, the rate of consanguineous marriages among the patients' parents, and clinical symptoms were not reported in many of the articles. Therefore, they were presented in Table 1.

Out of a total of 4,256 patients, at least one mutation had been reported for 2933 patients (68.9%) (Table 1). As shown in Table 2, 38 different MEFV gene mutations, including 37 substitutions and one small deletion, were identified. The highest number of mutations were found in exons 10, 2, 3, 5, and 1, respectively. No mutations were reported in other five exons. According to the Infevers database, 11 mutations were classified as pathogenic or likely pathogenic. The most common mutations among Iranian FMF patients were: p.M694V (20.27%), p.E148Q (10.27%), p.V726A (8.24%), p.M680I (both c.2040G > C and c.2040G > A) (7.2%), p.R761H (c.2282G > A) (2.1%), p.M694I (2.1%), p.P369S (c.1105C > T) (0.49%), p.A744S (c.2230G > T) (0.45%), and p.F479L (c.1437C > G) (0.18%). Each of these mutations was identified on 15 or more FMF mutated alleles. Other mutations had been reported on only one or a few alleles. Therefore, they were considered as rare in this study. In addition, the heterozygous forms of p.M694V (15.36%) and p.E148Q (14.93%), the homozygous form of p.M694V (11.45%), and the compound heterozygous form of p.M694V/p.V726A (7.44%) were the most frequent genotypes in our population (data not shown).

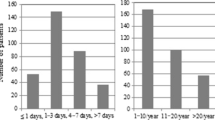

Not all 16 articles reported the geographic location or ethnic origin of the patients, however, we categorized FMF patients into six groups originated from northwest, north, central, south, west, and southwest. Our results showed that the frequencies of six common mutations in Iran, including p.M694V, p.E148Q, p.V726A, p.M680I, p.R761H, and p.M694I are significantly different in different parts of the country (Fig. 1). The variants of p.K618N (c.1854G > C), p.K716M (c.2147A > T), p.S614F (c.1841C > T), p.H300Q (c.900T > G), p.A66P (c.196G > C), p.R202W (c.604C > T), p.P313S (c.937C > T) , and p.A310D (c.929C > A) were not reported in the Infevers database. In addition, based on this database, 19 variants were categorized as likely benign, VUS, and not classified (Table 2).

Distribution of common MEFV gene mutations in different regions of Iran. It should be noted that only in nine articles it was possible to extract mutations based on the geographical location of patients (Mohammadnejad and Farajnia [20] & Sabokbar et al. [14] & Hosseini et al. [10] & Gharesouran et al. [19] & Bonyadi et al. [18] & Salehzadeh [22] & Ebadi et al. [15] & Bagheri and AbdiRad [17] & Rostamizadeh et al. [21]). Therefore, data presented here is taken from those nine articles

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review study on the spectrum of MEFV gene mutations among Iranian FMF patients. Our findings are in consistent with the results of global review studies. In fact, the mutations of p.M694V, p.E148Q, p.V726A, p.M680I (c.2040G > C), and p.M694I are responsible for three quarters or more of FMF patients originating from Middle Eastern populations [1, 2, 7, 24]. Based on haplotype analysis, it has been shown that many of the modern-day FMF chromosomes are of common ancestry and probably date back to pre-biblical times. This could be a possible reason for the high prevalence of the above five mutations [24, 25].

p.E148Q was found to be the second most common mutation among Iranian FMF patients (Table 2). This mutation has been reported to be the most common variant in the general population. Moreover, it is common even in parts of the world where FMF is rare [1]. The pathogenicity of this variant is still controversial; some studies have described it as benign and others have described it as VUS [26]. In addition, it may not cause an FMF phenotype even in the homozygous state [7]. Therefore, some researchers refer to it as a polymorphism rather than a mutation [7].

The third and fourth most common mutations in our population were p.V726A and p.M680I, respectively. Both of these mutations were classified as pathogenic in the Infevers database. It should be noted that p.M680I were reported in both forms of c.2040G > C and c.2040G > A in our population. Given that both forms were pathogenic in the Infevers database, the total frequency of them was calculated in this study. The frequency of p.R761H and p.M694I mutations in the current study was about 2%. In the Infevers database, these mutations had been categorized as likely pathogenic and pathogenic, respectively.

Examination of the literature revealed that certain MEFV gene mutations are more common in certain populations. For example, p.M694V is the most frequent mutation in patients from Denmark [27], Germany [28], Turkey [29, 30], Armenia [31,32,33], Western European populations including Italy [34, 35], Greek [36] and Spain [37], and Middle eastern populations including Lebanon [38, 39], Jordan [40, 41], Palestine [42] and Syria [43]. In addition, while p.M694I and p.V726A are known to be common among Arab populations in the Middle East [44], p.M680I is common in Turkish FMF patients [29, 30]. The frequency of these mutations is not the same among North African countries [44,45,46,47,48,49]. In total, it seems that the order of five most common MEFV gene mutations among Iranian FMF patients is most similar to that observed in Middle Eastern Arab populations [44].

To our knowledge, no studies have been carried out specifically to investigate MEFV gene mutations in FMF patients living in the eastern provinces of Iran. Therefore, the patients enrolled in the studies reviewed by us were categorized into six groups originated from northwest, north, central, south, west, and southwest (Fig. 1). The order and frequency of common mutations in the northwest were very similar to those observed at the country level. This could be due to the high number of Azeri Turkish patients in this study, who accounted for more than 65% of the total number of patients. Each of the other regions had distinct mutational orders and frequencies. The high frequency of p.M694I in the north, central, south, west, and southwest was the most important distinguishing feature of the mutations observed in these regions compared to those observed at the country level as well as at the northwest area.

Limitations

Using of different mutation detection methods in different studies may have resulted in a bias in the estimation frequency of MEFV gene mutations in this systematic review. As another limitation, patients were not sorted based on their geographical location in a number of studies. These subjects as well as the lack of information or limited information about the spectrum and frequency of MEFV gene mutations in some provinces of Iran were our challenges in achieving the exact spectrum and frequency of mutations in different geographical regions.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the five FMF founder mutations including p.M694V, p.E148Q, p.V726A, p.M680I, and p.M694I were the most common among Iranian FMF patients. The ranks and frequencies of these mutations were closer to those observed in the Mediterranean countries, especially in the Middle Eastern Arab populations. Although some comprehensive studies have been performed on Azeri Turkish patients living in northwestern Iran, studies in other areas, especially in eastern Iran, have been very limited. One reason for this observation could be due to the low frequency of FMF patients in those areas. Regardless of the reason for this, the exact spectrum and frequency of MEFV gene mutations among Iranian FMF patients remain unclear. Therefore, comprehensive future studies in different parts of the country are recommended.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- FMF:

-

Familial Mediterranean Fever

- MEFV gene:

-

Mediterranean fever gene

- STROBE checklist:

-

Strengthening of the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology checklist

References

Ozdogan H, Ugurlu S (2019) Familial mediterranean fever. Presse Med 48(1):e61–e76

Ben-Chetrit E, Touitou I (2009) Familial mediterranean fever in the world. Arthritis Care Res 61(10):1447–1453

Ebrahimi-Fakhari D, Schönland S, Hegenbart U, Lohse P, Beimler J, Wahlster L et al (2013) Familial Mediterranean fever in Germany: clinical presentation and amyloidosis risk. Scand J Rheumatol 42(1):52–58

Booth D, Gillmore J, Lachmann H, Booth S, Bybee A, Soytürk M et al (2000) The genetic basis of autosomal dominant familial Mediterranean fever. QJM 93(4):217–221

Stoffels M, Szperl A, Simon A, Netea MG, Plantinga TS, van Deuren M et al (2014) MEFV mutations affecting pyrin amino acid 577 cause autosomal dominant autoinflammatory disease. Ann Rheum Dis 73(2):455–461

Rowczenio DM, Iancu DS, Trojer H, Gilbertson JA, Gillmore JD, Wechalekar AD et al (2017) Autosomal dominant familial Mediterranean fever in Northern European Caucasians associated with deletion of p. M694 residue—a case series and genetic exploration. Rheumatology 56(2):209–213

Sarı İ, Birlik M, Kasifoğlu T (2014) Familial Mediterranean fever: an updated review. Eur J Rheumatol 1(1):21–31

Bidari A, Ghavidel-Parsa B, Najmabadi H, Talachian E, Haghighat-Shoar M, Broumand B et al (2010) Common MEFV mutation analysis in 36 Iranian patients with familial Mediterranean fever: clinical and demographic significance. Mod Rheumatol 20(6):566–572

Farivar S, Shiari R, Hadi E (2010) Molecular analysis of MEFV gene in Iranian children with familial Mediterranean fever. Indian J Rheumatol 5(2):66–68

Hosseini M, Dolatshahi E, Ebadi H, Zahedi-Shoolami L (2014) Familial Mediterranean fever in the Iranian population: MEFV mutations in different ethnic groups. Indian J Rheumatol 9(1):4–8

Mirhassani Moghaddam J, Zali MR, Taghizadeh F, Noroozi N, Narimani A, Peyman S et al (2004) MEFV gene mutations in Iranian patients with familial Mediterranean fever (FMF). J Sch Med Shahid Beheshti Univ Med Sci 28(4):315–320

Mohebbi SR, Haghighi MM, Damavand B, Bozorgi SM, Fatemi SR, Tahami A et al (2010) Molecular analysis of mutations in MEFV gene involved in patients with familial of Mediterranean fever referred to Taleghani hospital, Tehran, between 2006 and 2008. Med Sci J Islamic Azad Uni 20(2)

Sabokbar T, Malayeri A, Azimi C, Raeeskarami SR, Ziaee V, Aghighi Y et al (2014) Spectrum of mutations of familial Mediterranean fever gene in Iranian population. Ann Paediatr Rheum 3:11–17

Beheshtian M, Izadi N, Kriegshauser G, Kahrizi K, Mehr EP, Rostami M et al (2016) Prevalence of common MEFV mutations and carrier frequencies in a large cohort of Iranian populations. J Genet 95(3):667–674

Ebadi N, Shakoori A, Razipour M, Salmaninejad A, Yeganeh RZ, Mehrabi S et al (2017) The spectrum of Familial Mediterranean Fever gene (MEFV) mutations and genotypes in Iran, and report of a novel missense variant (R204H). Eur J Med Genet 60(12):701–705

Haghighat M, Moghtaderi M, Farjadian S (2017) Genetic analysis of southwestern Iranian patients with familial Mediterranean fever. Rep Biochem Mol Biol 5(2):117

Bagheri M, Rad IA (2017) Analysis of the most common three MEFV mutations in 630 patients with familial Mediterranean fever in Iranian Azeri Turkish population. Maedica 12(3):169

Bonyadi MJ, Gerami SMN, Somi MH, Dastgiri S (2015) MEFV mutations in Northwest of Iran: a cross sectional study. Iran J Basic Med Sci 18(1):53–57

Gharesouran J, Rezazadeh M, Ghojazadeh M, Ardabili MM (2014) Mutation screening of familial Mediterranean fever in the Azeri Turkish population: genotype-phenotype correlation and the clinical profile variability. Genetika 46(2):611–620

Mohammadnejad L, Farajnia S (2013) Mediterranean fever gene analysis in the Azeri Turk population with familial Mediterranean fever: evidence for new mutations associated with disease. Cell J 15(2):152–159

Rostamizadeh L, Vahedi L, Bahavarnia SR, Alipour S, Abolhasani S, Khabazi A et al (2020) Mediterranean fever (MEFV) gene profile and a novel missense mutation (P313H) in Iranian Azari-Turkish patients. Ann Hum Genet 84(1):37–45

Salehzadeh F (2015) Familial Mediterranean fever in Iran: a report from FMF registration center. Int J Rheumatol 2015:912137

Farjadian S, Bonatti F, Soriano A, Reina M, Adorni A, Graziano C et al (2019) A new MEFV gene mutation in an Iranian patient with familial Mediterranean fever. Reumatismo 71(2):85–87

Touitou I (2001) The spectrum of familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) mutations. Eur J Hum Genet 9(7):473–483

Jalkh N, Genin E, Chouery E, Delague V, Medlej-Hashim M, Idrac CA et al (2008) Familial Mediterranean fever in Lebanon: founder effects for different MEFV mutations. Ann Hum Genet 72(1):41–47

Giancane G, Ter Haar NM, Wulffraat N, Vastert SJ, Barron K, Hentgen V et al (2015) Evidence-based recommendations for genetic diagnosis of familial Mediterranean fever. Ann Rheum Dis 74(4):635–641

Mortensen S, Hansen A, Lundgren J, Barfod T, Ambye L, Dunø M et al (2020) Characteristics of patients with familial Mediterranean fever in Denmark: a retrospective nationwide register-based cohort study. Scand J Rheumatol 49(6):489–497

Lainka E, Bielak M, Lohse P, Timmann C, Stojanov S, Von Kries R et al (2012) Familial Mediterranean fever in Germany: epidemiological, clinical, and genetic characteristics of a pediatric population. Eur J Pediatr 171(12):1775–1785

Yalçınkaya F, Group TFS (2005) Familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) in Turkey: results of a nationwide multicenter study. Medicine 84(1):1–11

Akar N, Misiroglu M, Yalcinkaya F, Akar E, Cakar N, Tümer N et al (2000) MEFV mutations in Turkish patients suffering from familial Mediterranean fever. Hum Mutat 15(1):118–119

Sarkisian T, Ajrapetyan H, Shahsuvaryan G (2005) Molecular study of FMF patients in Armenia. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy 4(1):113–116

Sarkisian T, Hayrapetyan H, Beglaryan A, Shahsuvaryan G, Yeghiazaryan A (2007) Molecular diagnosis of familial mediterranean fever in armenians. NEW Armen Med J 1(1):33–40

Moradian MM, Sarkisian T, Ajrapetyan H, Avanesian N (2010) Genotype–phenotype studies in a large cohort of Armenian patients with familial Mediterranean fever suggest clinical disease with heterozygous MEFV mutations. J Hum Genet 55(6):389–393

Manna R, Cerquaglia C, Curigliano V, Fonnesu C, Giovinale M, Verrecchia E et al (2009) Clinical features of familial Mediterranean fever: an Italian overview. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 13(Suppl 1):51–53

La Regina M, Nucera G, Diaco M, Procopio A, Gasbarrini G, Notarnicola C et al (2003) Familial Mediterranean fever is no longer a rare disease in Italy. Eur J Hum Genet 11(1):50–56

Giaglis S, Papadopoulos V, Kambas K, Doumas M, Tsironidou V, Rafail S et al (2007) MEFV alterations and population genetics analysis in a large cohort of Greek patients with familial Mediterranean fever. Clin Genet 71(5):458–467

Aldea A, Calafell F, Aróstegui JI, Lao O, Rius J, Plaza S et al (2004) The west side story: MEFV haplotype in Spanish FMF patients and controls, and evidence of high LD and a recombination “hot-spot” at the MEFV locus. Hum Mutat 23(4):399–406

El Roz A, Ghssein G, Khalaf B, Fardoun T, Ibrahim J-N (2020) Spectrum of MEFV Variants and Genotypes among Clinically Diagnosed FMF Patients from Southern Lebanon. Med Sci 8(3):35

Medlej-Hashim M, Serre J-L, Corbani S, Saab O, Jalkh N, Delague V et al (2005) Familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) in Lebanon and Jordan: a population genetics study and report of three novel mutations. Eur J Med Genet 48(4):412–420

Habahbeh LA, Al Hiary M, Al Zaben SF, Al-Momani A, Khasawneh R, Abu Mallouh M et al (2015) Genetic profile of patients with familial Mediterranean fever (FMF): single center experience at King Hussein Medical Center (KHMC). Med Arh 69(6):417–420

Alzyoud R, Alsweiti M, Maittah H, Zreqat E, Alwahadneh A, Abu-Shukair M et al (2018) Familial Mediterranean fever in Jordanian Children: single centre experience. Mediterr J Rheumatol 29(4):211–216

Ayesh SK, Nassar SM, Al-Sharef WA, Abu-Libdeh BY, Darwish HM (2005) Genetic screening of familial Mediterranean fever mutations in the Palestinian population. Saudi Med J 26(5):732–737

Jarjour RA, Abou JR (2017) Mutations of familial Mediterranean fever in Syrian patients and controls: evidence for high carrier rate. Gene Rep 6:87–92

Ait-Idir D, Djerdjouri B (2020) Differential mutational profiles of familial Mediterranean fever in North Africa. Ann Hum Genet 84(6):423–430

Belmahi L, Cherkaoui IJ, Hama I, Sefiani A (2012) MEFV mutations in Moroccan patients suffering from familial Mediterranean Fever. Rheumatol Int 32(4):981–984

El Gezery DA, Abou-Zeid AA, Hashad DI, El-Sayegh HK (2010) MEFV gene mutations in Egyptian patients with familial Mediterranean fever. Genet Test Mol Biomark 14(2):263–268

Zarouk WA, El-Bassyouni HT, Ramadan A, Fayez AG, Esmaiel NN, Foda BM et al (2018) Screening of the most common MEFV mutations in a large cohort of Egyptian patients with Familial Mediterranean fever. Gene Rep 11:23–28

Talaat HS, Sheba MF, Mohammed RH, Gomaa MA, El Rifaei N, Ibrahim MFM (2020) Genotype mutations in Egyptian children with familial mediterranean fever: clinical profile, and response to Colchicine. Mediterr J Rheumatol 31(2):206–213

Mansour AR, El-Shayeb A, El Habachi N, Khodair MA, Elwazzan D, Abdeen N et al (2019) Molecular patterns of MEFV gene mutations in Egyptian patients with familial Mediterranean fever: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Inflam

Acknowledgements

We hereby express our gratitude and appreciation to the Student Research Committee and Deputy for Research and Technology, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran, for reviewing, transferring to the ethics research committee and final approval of the project.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KM, Dr. RA and KG had the idea of the topic. KM, AM, SK and MK performed the literature search. KM analyzed data and drafted the manuscript. RA and KG supervised the study process and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran (Ethics code: IR.KUMS.REC.1399.976, project number: 990822).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alibakhshi, R., Mohammadi, A., Ghadiri, K. et al. Spectrum of MEFV gene mutations in 4,256 familial Mediterranean fever patients from Iran: a comprehensive systematic review. Egypt J Med Hum Genet 23, 5 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43042-022-00222-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43042-022-00222-y