Abstract

Mating-type genes are central to sexual reproduction in ascomycete fungi and result in the establishment of reproductive barriers. Together with hybridization, they both play important roles in the evolution of fungi. Recently, potential hybridization events and MAT genes were separately found in the Elata Clade of Morchella. Herein, we characterized the MAT1–1-1 and MAT1–2-1 genes of twenty-two species in the Esculenta Clade, another main group in the genus Morchella, and proved heterothallism to be the predominant mating strategy among the twenty-two species tested. Ascospores of these species were multi-nuclear and had many mitochondrial nucleoids. The number of ascospore nuclei might be positively related with the species distribution range. Phylogenetic analyses of MAT1–1-1, MAT1–2-1, intergenic spacer (IGS), and partial histone acetyltransferase ELP3 (F1) were performed and compared with the species phylogeny framework derived from the ribosomal internal transcribed spacer region (ITS) and translation elongation factor 1-alpha (EF1-a) to evaluate their species delimitation ability and investigate potential hybridization events. Conflicting topologies among these genes genealogies and the species phylogeny were revealed and hybridization events were detected between several species. Different evolutionary patterns were suggested for MAT genes between the Esculenta and the Elata Clades. Complex evolutionary trajectories of MAT1–1-1, MAT1–2-1, F1 and IGS in the Esculenta Clade were highlighted. These findings contribute to a better understanding of the importance of hybridization and gene transfer in Morchella and especially for the appearance of reproductive modes during its evolutionary process.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

In fungi, sexual reproduction is regulated by genomic regions called mating-type (MAT) loci (Kronstad and Staben 1997; Debuchy et al. 2010; Casselton and Feldbrügge 2010), which operate on the establishment of reproductive barriers, determine mating compatibility and result in speciation (Coppin et al. 1997; Lee et al. 2010; Palumbi 2009; Swanson and Vacquier 2002). In filamentous ascomycetes, the mating-type system is bipolar and has a single MAT locus called MAT1 with two alternate forms as master regulators of sexual reproduction: the MAT1–1-1 and the MAT1–2-1 genes, respectively, encoding for alpha-box and a high mobility group (HMG) domain proteins (Metzenberg and Glass 1990; Debuchy et al. 2010). Due to their dissimilar sequences, the two forms of the MAT locus are referred to as idiomorphs instead of alleles (Metzenberg and Glass 1990). Filamentous ascomycetes have two main sexual reproductive modes: homothallism and heterothallism. Homothallic fungi are self-fertile and can complete the sexual cycle without a mating partner. Typically, a single homothallic strain harbors both MAT idiomorphs (linked or unlinked) in the same haploid nucleus (Debuchy et al. 2010). On the contrary, heterothallic fungi are self-sterile, contain only one of the two MAT genes, and need the participation of an opposite mating type partner to reproduce.

Reproductive modes of fungi are assumed to have a great influence on the evolutionary trajectory of their genomes (Burt 2000). In recent years, MAT genes have gained significant attention in evolutionary biology: on the one hand because of the general relationship between the evolution of reproductive genes and the reproductive modes of individuals (Paoletti et al. 2006; Walters and Harrison 2008; Wik et al. 2008), and on the other hand because MAT genes are known to be evolutionarily dynamic with high evolutionary rates (Gioti et al. 2012; Martin et al. 2013; Sun and Heitman 2015). Therefore, MAT gene sequences have often been used to study evolutionary trends of mating systems (Fraser et al. 2007; Wik et al. 2008) and population genetics (Zhan et al. 2007; Groenewald et al. 2007). Because of the high evolutionary rates of MAT genes, some studies inferred a phylogenetic relationship suggesting that the phylogenies of MAT genes were consistent with other genes (Groenewald et al. 2006; Yokoyama et al. 2006; Lopes et al. 2017; O’Donnell et al. 2004; Duong et al. 2013; Du et al. 2017) whereas others found conflicting topologies (Wik et al. 2008; Strandberg et al. 2010).

True morels belong to the genus Morchella (Ascomycota, Pezizales, Morchellaceae), are widely known for their iconic edible ascomata and are among the world’s most prized edible fungi. The Morchella genus comprises the Esculenta Clade (yellow morels), the Elata Clade (black morels), and the Rufobrunnea Clade (blushing morels) with more than seventy species in total (Du et al. 2019b). Considering their important economic value, understanding the reproductive biology of these species is not only of fundamental but also of applied relevance, for example for artificial cultivation and cultivar breeding. However, knowledge about MAT genes in Morchella is currently limited to fourteen species from the Elata Clade. For these species, a heterothallic sexual cycle has been proposed while the phylogeny of MAT genes is consistent with other genes (Du et al. 2017). Species in the Esculenta Clade not only have a distinguished morphology from the Elata Clade, but also favor different ecological niches (Du et al. 2012; Kuo et al. 2012). Their reproductive modes are still unknown and the usefulness of MAT genes for species identification of MAT genes needs to be investigated. Additionally, considering that multiple hybridization events were detected in the Elata Clade (Du et al. 2016, 2019a), the F1 and IGS genes were chosen to assess whether they can be used for species identification and for the identification of potential hybridization events in the Esculenta Clade, based on previous studies focusing on the Elata Clade (Du et al. 2016) and the genus Fusarium (Mbofung et al. 2006).

The present study therefore sought: (i) to isolate and characterize the MAT1–1-1 and MAT1–2-1 genes of twenty-two yellow morel species; (ii) to illuminate the reproductive mode of these twenty-two species; (iii) to evaluate the MAT1–1-1 and MAT1–2-1 polymorphism intra- and interspecies; (iv) to infer the usefulness of the MAT1–1-1 and MAT1–2-1 genes as phylogenetic markers in the Esculenta Clade; and (v) to investigate the potential hybridization events among these species. Considering the increased interest in morel cultivation in China (Du et al. 2019a), description of the reproductive modes of these species is of high applied value.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Obtaining of MAT1–1-1 and MAT1–2-1 sequences

The genome of Mes-21 was sequenced using an Illumina HiSeq 2500 Genome Analyzer (Illumina Inc., USA) by Genoseq Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China) based on highly purified total genomic DNA isolated from the fungal mycelia culture. The genome was assembled by SOAPdeNovo2 (Zerbino et al. 2008) to first construct contigs based on the short insert libraries, then joining these to scaffolds using paired-end information, followed by local reassembly of unresolved gap regions. In order to detect the best assembly(s), kmer levels were respectively run at 41, 43, 45, 49 and 55, and an optimised k-mer size of 41 was suggested. The genome data of Mes-21 generated in this project has been deposited at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the submission no. SUB6606995.

MAT1–1-1 and MAT1–2-1 were identified using BLASTn and BLASTx against the NCBI nucleotide and protein database by sequence similarity searches (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/) in the genome of Mes-21. The alpha-box- and HMG-containing sequences of M. importuna (KY508074 and KY508167) and M. sextelata (KY508145 and KY508228) from the Elata Clade were chosen for BLAST analysis of MAT1–1-1 and MAT1–2-1 in the Mes-21 genome.

Fungal materials and species identification

Eighty-three samples collected in China, Croatia and France between 2016 and 2019 were used in this study. Based on two-gene phylogenetic species recognition analysis via nuc-rDNA internal transcribed spacer region (ITS) and translation elongation factor 1-α (EF1-a) gene, the samples were characterized and belonged to twenty-two phylogenetic species of Esculenta Clade in the genus Morchella, namely M. steppicola, M. yangii, M. yishuica, M. clivicola, M. dunensis, M. palazonii, M. americana, M. esculenta, M. galilaea, Mes-6, Mes-9, Mes-10, Mes-15, Mes-19, Mes-20, Mes-21, Mes-22, Mes-23, Mes-24, Mes-25, Mes-26, and Mes-27 (Table 1). At least two samples from each species were selected, except for M. steppicola and Mes-24 since only one sample was obtained of each. All the collections used in the present study were dried with silica and housed in the Fungal Herbarium of Chongqing Normal University, Chongqing City, China (FCNU). Information on these samples is detailed in Table 1.

Selection of loci

Two mating-type genes (MAT1–1-1 and MAT1–2-1), herein referred to as reproductive genes, were investigated in this study. The nuc-rDNA internal transcribed spacer region (ITS) and translation elongation factor 1-α (EF1-a) gene were used to identify these eight-three samples in this study (Table 1). Additionally, 28S–18S ribosomal intergenic spacer region (IGS) and partial sequences of histone acetyltransferase ELP3 (F1) with assumed functions independent of sexual reproduction in Morchella were selected for comparative purposes. IGS and F1 are referred to as non-reproductive genes in this paper.

Single spore isolates and cultural conditions

Twenty single ascospores were randomly isolated from each species, except for M. steppicola, Mes-24 and Mes-27, because samples from the three species were immature. Ascospores were washed, suspended in sterilized water, and 200 μL of a solution adjusted to a concentration of 200–300 ascospores mL− 1 was spread on potato dextrose agar (PDA) (Solarbio, China) and incubated at 23–25 °C for 1–2 days. Single germinated ascospores were picked using a dissecting needle under a dissecting microscope (Zeiss 455,094), and transferred to a new PDA petri dish, and incubated at 23–25 °C for 2 weeks. Then, the mycelium were harvested by scraping the surface of PDA using a clean surgical blade and used for DNA extraction.

DNA extraction

Samples (mycelium/ascomata) were ground to a fine powder in a 1.5-mL microcentrifuge tube using a Kontes pellet pestle (Kaimu, China). Once pulverized, the samples were suspended in 700 μL CTAB extraction buffer (100 mM Tris–Cl pH 8.4, 1.4 M NaCl, 25 mM EDTA, 2% CTAB), and incubated for 1.5–2.0 h at 65 °C during which time they were gently inverted 3–5 times. After the samples were cooled to room temperature, 700 μL chloroform–isoamyl alcohol (24:1) was added to each tube. The mixture was vortexed briefly, centrifuged at 12,000 g for 10 min, and 500 μL of the upper phase was carefully transferred to a new 1.5-mL microcentrifuge tube. After a second chloroform–isoamyl alcohol (24:1) extraction was performed, the supernatant was transferred to a new 1.5-mL microcentrifuge tube and an equal volume of 100% isopropanol at 20 °C was added to each tube. The tube contents were mixed briefly by inversion to obtain a homogeneous solution and then they were stored overnight at 20 °C to precipitate total genomic DNA. After the tubes were warmed to room temperature, they were centrifuged at 12,000 g for 10 min and the supernatant was discarded. The DNA pellet was washed consecutively with 70 and 100% ethanol, air-dried and resuspended in 100 μL of sterile double-distilled H2O. All genomic DNA samples were stored frozen at − 20 °C.

PCR amplification and DNA sequencing

The primer sequences of MAT1–1-1, MAT1–2-1, ITS, EF1-a, IGS and F1 genes are reported in Table 2 and used for the following PCR and DNA sequencing. PCR was carried out on an ABI 2720 Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) using the following program: pre-denaturation at 94 °C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 53 °C for 30 s and elongation at 72 °C for 30 s. Afterwards, a final elongation at 72 °C for 8 min was performed. PCR products were sent to Kunming Shuoqing Biotech Ltd. to carry out DNA sequencing. Raw sequence data of MAT1–1-1, MAT1–2-1, ITS, EF1-a, IGS and F1 were edited and aligned with SeqMan implemented in Lasergene v7. 1 (DNASTAR Inc., USA) and automatically aligned with MAFFT v6.853 using the E-INS-i strategy (Katoh et al. 2002). Aligned sequences were visually inspected and manually adjusted using BioEdit v7.0.9. Sequences generated in the present study have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers MN513618-MN513997 and MN513426-MN513494.

Identification of species and phylogenetic analysis of all the loci

Considering the difficulty of accurately distinguishing all the morel species according to morphology, species identification of all the samples used in this study was previously performed based on molecular phylogenetic analysis of the ITS rDNA and EF1-a datasets, which were previously used for species identification in the genus Morchella (O’Donnell et al. 2011, Du et al. 2012). For the concatenated and two individual matrices (ITS-EF1-a, MAT1–1-1 and MAT1–2-1), the taxon M. steppicola was used as the outgroup in this study as inferred by O’Donnell et al. (2011) and Du et al. (2012). Because of our inability to sequence locus F1 and IGS for M. steppicola, M. americana was used as the outgroup in the F1 datasets as inferred by O’Donnell et al. (2011) and Du et al. (2012); whereas mid-rooted trees were generated for the IGS datasets as no suitable taxon could serve as the outgroup. All eighty-three samples from twenty-two species successfully generated amplicons from ITS, EF1a, MAT1–1-1 and MAT1–2-1. However, some samples failed to generate amplicons of IGS and F1 and were shown in Table 1.

Using these generated sequences, phylogenetic analyses were performed on the following datasets: (i) for the combined ITS and EF1-a dataset, 83 sequences, 22 species; (ii) for the MAT1–1-1 dataset, 83 sequences, 22 species; (iii) for the MAT1–2-1 dataset, 83 sequences, 22 species; (iv) for the IGS dataset, 68 sequences, 20 species; and (v) for the F1 dataset, 69 sequences, 20 species. The combined nucleotide sequences of ITS and EF1-a were used to construct the species tree for all samples in Table 1.

Phylogenetic analyses using a Maximum parsimony (MP) analysis and Maximum Likelihood (ML) analysis were subsequently conducted on PAUP V 4.0b10 (Swofford 2002) and RAxML v7.2.6 (Stamatakis 2006), respectively. For the concatenated two-gene matrices, single-gene analyses were conducted to assess incongruence among individual genes using the MP method (results not shown). Because no well-supported (BS > 70%) conflict was detected among the topologies of the two genes, their sequences were then concatenated together for further analyses. For the two-gene datasets, a partitioned model, with the model (GTR + I + G) for both of genes, was used by defining the sequences of ITS and EF1-a as two partitions. For the MP analysis, heuristic searches were conducted with tree bisection–reconnection branch swapping algorithm (TBR) after exclusion of uninformative characters, random sequence additions, and with Multrees option on. Bootstrap values (BP) of the most parsimonious trees were obtained from 1000 replications. Gaps were defined as a fifth character in all analyses. For the ML analyses, all of the parameters were kept at their default settings, except that the model was set as GTRGAMMAI (Stamatakis 2006) which was applied for the concatenated and four individual matrices (ITS-EF1-a, MAT1–1-1, MAT1–2-1, F1 and IGS), while statistical support was obtained using nonparametric bootstrapping with 1000 replicates. Trees generated by the two analyses were viewed and exported in FigTree v. 1.4.2 (Rambaut 2009).

Mating-type detection and screening for single ascospore culture

Considering that the sequence lengths of MAT1–1-1 and MAT1–2-1 are 708 bp and 869–880 bp, respectively, mating-type gene detection of the 380 single ascospores could be performed by observing amplicon length over an ultraviolet transilluminator after electrophoresis for first screening. This method greatly reduced the sequencing cost and accelerated mating-type detection.

Ratio assessment of mating types and karyological analysis

The ratios of both mating types were assessed for intra- and interspecies single-spore isolates. The mating-type ratios within and among species were compared. Ascospores were stained with DAPI (4′-6-diamidino-2-phenilindole) to visualize nuclei. Pools of purified ascospores were incubated for 15 min in the staining reagent (4 mM DAPI, 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, and 20% glycerol) directly on the microscope slide. Ascospore nuclei were observed under fluorescent microscopy and laser scanning microscopy with an Olympus Fluoview FV1000 laser scanning microscope.

RESULTS

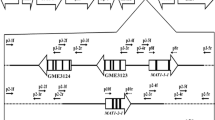

Identification of MAT1–1-1 and MAT1–2-1 genes in the genome of yellow morels

Through the BLAST analysis of the alpha-box- and HMG-containing sequences of M. importuna (KY508074 and KY508167) and M. sextelata (KY508145 and KY508228) belonging to the Elata Clade of Morchella, we revealed one MAT1–1-1 and one MAT1–2-1 genes in Morchella sp. Mes-21 genome. This was confirmed by BLAST analysis in Genbank and was best matching with M. importuna (APF29253 and APF29258), Tuber indicum (AHE80940, AHE80941) and Penicillium kewense (CBY44653), respectively. The primer pairs EMAT11L/EMAT11R and EMAT12L/EMAT12R were designed on the most conserved regions of the alpha-box domains of MAT1–1-1 and HMG-box of MAT1–2-1 genes, and then were used to amplify orthologs of the MAT1–1-1 and MAT1–2-1 genes from the eighty-three samples of twenty-two species.

Genetic diversity of MAT idiomorphs

The most conserved regions of MAT1–1-1 and MAT1–2-1 were successfully amplified from the twenty-two species. MAT1–1-1 was 708 bp and contained two exons and one intron while MAT1–2-1 varied between 869 and 880 bp and included three exons and four introns. As the basal taxa of the Esculenta Clade, the length of MAT1–1-1 of M. steppicola was similar to the ones of other species in Esculenta Clade without deletion or insertion; however, the length of MAT1–2-1 for this species was much longer than the other species since it contained an insertion of fourteen bases. The nucleotide sequences alignment of MAT1–1-1 included a total of 654 sites after trimming and contained 53 parsimony-informative sites and 67 singleton variable sites. Its estimated nucleotide diversity (pi) was 0.0177 with 120/654 (18.35%) variable nucleotide sites. The MAT1–2-1 alignment consisted of a total of 827 sites after trimming and included 74 parsimony-informative sites and 84 singleton variable sites. It had an estimated nucleotide diversity (pi) of 0.0237 with 158/827 (19.10%) variable nucleotide sites.

For both MAT loci, higher levels of nucleotide diversity were found for interspecies than intraspecies. An lower diversity was observed in MAT1–1-1 than MAT1–2-1 for interspecies, but not for intraspecies (Table 1). The nucleotide diversity of MAT1–1-1 was higher than MAT1–2-1 in M. clivicola, M. esculenta, M. galilaea, M. dunensis, M. yangii, Mes-9, Mes-10, Mes-19, and Mes-20, but lower than MAT1–2-1 in M. amerciana, Mes-6, Mes-15, Mes-21, Mes-22, and Mes-25. Morchella palazonii had the highest intraspecies nucleotide diversity for MAT1–1-1 while Mes-21 had the highest intraspecies nucleotide diversity for MAT1–2-1. The protein length of MAT1–1-1 among these species was conserved at 198 amino acids and the protein length of MAT1–2-1 was conserved at 244 amino acids, except for M. steppicola with 241 amino acids.

Mating-type ratio of single spores and reproductive modes of the species

From one to nine samples for each species were used to investigate the presence of MAT1–1-1 and MAT1–2-1 genes. Our results showed that both MAT amplicons were present in each sample of these species. To further determine whether these species were secondary homothallic or heterothallic, twenty single ascospores were isolated from each species, except for M. steppicola, Mes-24 and Mes-27, because no ascospores could be obtained from the culture of M. steppicola, the sample of Mes-24 was old and the samples of Mes-27 were immature. Each single spore always showed only a single mating type, either the MAT1–1-1 or the MAT1–2-1 gene. No spores harboring both mating types were found. The ratio of MAT1–1-1:MAT1–2-1 of single ascospores in each species was nearby 1:1 and consistent with the null hypothesis (no deviation from a theoretical segregation ratio of 1:1, MAT1–1-1:MAT1–2-1). Therefore, the two mating types occurred equally among ascospores of a single ascomata and the reproductive modes of nineteen species were assumed to be heterothallic.

The results of fluorescence microscopy suggest that ascospores of these species were multinuclear. The number of nuclei in each ascospores roughly divided these species into three groups (Fig. 1 and Table 3): (1) having two, four, six, eight, or more than ten nuclei, including Mes-6, Mes-9, Mes-19, Mes-20, Mes-22, Mes-23, M. esculenta, M. dunenesis, and M. yangii; (2) having more than ten nuclei, including Mes-10, Mes-15, Mes-21, Mes-25, Mes-26, M. americana, M. palazonnii, M. yishuica, and M. clivicola; and (3) having more than twenty nuclei, including M. galilaea.

Notably, when observed under the laser scanning confocal microscopy, not only multi-nuclei, but also many mitochondrial nucleoids were observed in ascospores of each species (Fig. 2). Due to the many mitochondria nucleoids in ascospores, we could not further count their nuclei under the laser scanning confocal microscopy. The results from both the fluorescence microscopy and the laser scanning confocal microscopy suggest that ascospores in these species were haploid homokaryotic multinuclear that harbored many mitochondria nucleoids.

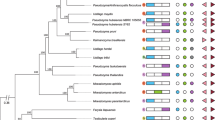

Genealogies from reproductive gene (MAT1–1-1 and MAT1–2-1) datasets and species phylogeny

A species phylogeny framework for the twenty-two species (Fig. 3) was constructed using the ITS and EF1-a combined dataset with 2019 bp using the maximum likelihood and parsimony phylogenetic method which was also used for inferring the genealogies of both MAT1–1-1 and MAT1–2-1 datasets, resepctively with 654 bp and 828 bp (Figs. 4 and 5). The phylogenetic trees of MAT1–1-1 and MAT1–2-1 were used to represent the reproductive genes phylogeny of these species (Figs. 4 and 5). Both the MP and ML trees of MAT1–1-1 and MAT1–2-1 had the similar topological phylogenies, but their backbones were weakly supported. The species trees supported that each of the twenty-two species formed a monophyletic group; however, the phylogenetic trees for MAT1–1-1 and MAT1–2-1 displayed several topological conflicts with the species tree and between each other (Figs. 3, 4 and 5).

First, the topological positions of the species differed between the MAT1–1-1 genealogy and the species tree (Figs. 3 and 4). In the species tree, M. clivicola, M. yishuica, M. yangii and Mes-20, respectively formed well-supported monophyletic groups, in contrast to the MAT1–1-1 genealogy, in which samples from these species did not form monophyletic groups. Samples from Mes-22 and Mes-23 could be well divided into two monophyletic groups with high support (ML and MP bootstrap > 80%) in the species tree where the relationship between them was indicated to be very close; however, the MAT1–1-1 genealogy supported samples from Mes-22 and Mes-23 belonging to one species with 100% ML and MP bootstrap value.

Second, the topological positions of the species differed between the MAT1–2-1 genealogy and the species tree. In the species tree, M. dunensis, Mes-6 and Mes-21 respectively formed well-supported monophyletic groups (ML and MP bootstrap > 85%) and were closely related sister groups; however, in the MAT1–2-1 genealogy, all samples from these three species formed a well-supported monophyletic group (ML and MP bootstrap = 98%). In the species tree, Mes-9 and Mes-20 could each form a well-supported monophyletic group, in contrast to the MAT1–2-1 genealogy, in which samples from two species did not form monophyletic groups. Samples from Mes-22 and Mes-23 could be well divided into two monophyletic groups with high support (ML and MP bootstrap > 80%) in the species tree; however, the MAT1–2-1 genealogy clustered most of the samples from both Mes-22 and Mes-23 into one monophyletic group (ML and MP bootstrap = 100%), except for FCNU1085, which was grouped together with M. dunensis, Mes-6 and Mes-21 and presumed to be a hybrid individual.

Third, the placement of these species also differed between the MAT1–1-1 and MAT1–2-1 genealogy (Figs. 4 and 5). Samples from Mes-9 and Mes-20 did not form monophyletic groups in either the MAT1–1-1 genealogy or the MAT1–2-1 genealogy, both of which is in conflict with the species phylogeny, while they showed different topological positions between each other as well. Samples from Mes-10 had no variation on MAT1–2-1 sequences while they highly varied on MAT1–1-1 sequences. The same phenomenon was found in M. palazonii and M. dunensis. Samples from Mes-25 had no variation on MAT1–1-1 sequences while they highly varied on MAT1–2-1 sequences. The same phenomenon was found in M. americana and Mes-6.

Genealogies from non-reproductive (F1 and IGS) datasets and species phylogeny

The primers of F1 and IGS developed in this study did not result in an amplification product for fourteen and fifteen of the samples used in the present study, respectively, although we redesigned new primers and extracted DNA several times to amplify these samples, we always failed. The final aligned lengths of F1 and IGS datasets used for generating phylogenetic trees were, respectively, 755 bp and 909 bp. The MP and ML trees of F1 and IGS had different topological structures. Though the same samples were always clustered together in both MP and ML trees of F1, the placements of branches always changed and their backbones were weakly supported. For the MP and ML trees of IGS, it’s the similar case as the ones of F1. Conflicts were found among the genealogies of F1 (Fig. 6) and IGS (Fig. 7) and the species phylogeny (Fig. 3).

In the F1 genealogy, samples from M. steppicola and Mes-24 failed to generate amplicons, and only one sample from each of the Mes-10, Mes-26, and M. palazonii obtained F1 amplicons, so when conflicts between the F1 phylogeny and the species phylogeny were considered, these five species were excluded. Samples from M. americana, M. clivicola, M. yishuica, Mes-15, and Mes-27 each formed a monophyletic group in the F1 genealogy as well as in the species phylogeny, although the placements of the five species differed between the F1 genealogy (Fig. 6) and the species tree (Fig. 3). Samples of Mes-6 did not form a monophyletic group in the F1 genealogy and the sample FCNU1035 from this species formed a monophyletic group together with FCNU1097 of Mes-25 with high support (ML and MP bootstrap > 95%). This indicated that some hybridization events might have happened between Mes-6 and Mes-25, and that FCNU1035 might be a hybrid. Samples from M. esculenta, Mes-9 and Mes-20 did not form monophyletic groups in the F1 genealogy. Samples of M. galilaea also did not form a monophyletic group as well as in the F1 genealogy, whereas one sample of this species, FCNU1064, from this species formed a monophyletic group with three samples of Mes-19, namely FCNU1069, FCNU1070 and FCNU1071. This indicated that some hybridization events might have happened between M. galilaea and Mes-19, and that FCNU1064 might be a hybrid. Samples from M. dunensis, M. yangii and Mes-21 did not form monophyletic groups, and samples from Mes-22 and Mes-23 formed a monophyletic group in the F1 genealogy.

Samples from M. steppicola and Mes-24 failed to generate IGS amplicons and only one of the samples of M. americana, Mes-10, Mes-25, and Mes-27 had amplicons from IGS, thus, these five species were excluded. Samples from M. clivicola, M. yishuica and Mes-15 each formed a monophyletic group in the IGS genealogy as well as in the species phylogeny. Samples from M. esculenta, M. palazonnii, M. dunensis, M. yangii, Mes-6, Mes-9, Mes-19, Mes-20, Mes-21, Mes-22, Mes-23 and Mes-26 did not form monophyletic groups in the IGS genealogy. One sample from M. dunensis, one sample from M. esculenta, two samples from Mes-20 and five samples from Mes-23 formed a monophyletic group with high support (ML and MP bootstrap > 95%). Three different IGS sequences were obtained from the four samples of Mes-21 (FCNU1080, FCNU1081, FCNU1083, and FCNU1084), and the IGS sequence of FCNU1080 and those of the three samples of M. yangii were clustered into a monophyletic group together. Three different IGS sequences from three samples of M. esculenta (FCNU1038, FCNU1039 and FCNU1041) and two from two samples of Mes-26 (FCNU1098 and FCNU1099) were obtained. The IGS sequences of FCNU1088 and FCNU1089 of Mes-22 and that of FCNU1099 of Mes-26 were grouped into a monophyletic group with high support (ML and MP bootstrap > 95%), suggesting that some hybridization events might have happened between Mes-22 and Mes-26.

Genealogical conflicts among MAT1–1-1, MAT1–2-1, F1, IGS, and species phylogeny

Conflicts were identified among the MAT1–1-1, MAT1–2-1, F1, IGS, and species phylogenies. The percentages of species in MAT1–1-1, MAT1–2-1, F1, and IGS genealogies which were in conflicted with species phylogeny were 30, 35, 66.7 and 81.3%, respectively (Table 4). The IGS genealogy had the most conflicts with species phylogeny, followed by F1, MAT1–2-1, and MAT1–1-1. Herein, the conflicts mainly referred to samples forming a monophyletic group in the species phylogeny but not in the four other genealogies. It is interesting that M. yishuica and Mes-15 did not have conflicts among the four genes genealogies and with the species phylogeny. For M. americana and Mes-27, except IGS with only one sample having amplicons in both species, no conflicts were found in the MAT1–1-1, MAT1–2-1 and F1 genealogies. Among the four genes, the success rate of amplification in IGS was the lowest.

The phylogenies of reproductive genes (MAT1–1-1 and MAT1–2-1) showed more resolution in these yellow morel species than the non-reproductive genes (F1 and IGS) (Figs. 4, 5, 6 and 7). In the MAT1–1-1 and MAT1–2-1 genealogies, fourteen and fifteen well-supported branches consistent with species phylogeny were formed, respectively (Figs. 4 and 5). In the F1 and IGS genealogies, only five or three well-supported branches and consistent with the species phylogeny were formed, respectively (Figs. 4 and 5).

TAXONOMY

Not applicable.

DISCUSSION

The availability of the genome sequence of Mes-21 created the opportunity to unveil MAT loci and mating strategies of the Esculenta Clade in the genus Morchella. In this study, primers were developed to amplify and sequence MAT1–1-1 and MAT1–2-1 genes from twenty-two species of the Esculenta Clade. Phylogenies resulting from these MAT sequences were compared with those resulting from the analyses of F1 (Du et al. 2016), IGS and a species phylogeny framework of Morchella and revealed multiple conflicts among them.

Comparison of MAT loci provides insights into the evolution of the genus Morchella

In the Elata Clade, the length of MAT1–1-1 (729–736 bp) is longer than MAT1–2-1 (398–408 bp) (Du et al. 2017). In the Esculenta Clade, the current results indicate that MAT1–1-1 (651–654 bp) is shorter than MAT1–2-1 (813–827 bp). This difference indicated that the mating-type genes in the Elata and Esculenta Clades appear to have a differential evolutionary history. Analyses of the MAT sequence showed higher levels of nucleotide diversity (pi) in both MAT1–1-1 (0.0178) and MAT1–2-1 (0.0236) within these species than intraspecies nucleotide diversity (pi). This indicated that MAT genes evolved rapidly among morel species. Strong purifying selection against deleterious mutations were suggested in MAT genes (Turgeon 1998; Heitman 2015), which probably resulted in the low intraspecific polymorphism observed in MAT genes of morels. Additionally, MAT1–2-1 was found to be more variable than MAT1–1-1 among the twenty-two species, which is consistent with the results in the Elata Clade (Du et al. 2017). Du et al. (2017) suggested that different sexual competences of MAT1–1-1 and MAT1–2-1 might exist in black morels which deserved to be investigated in yellow morels.

Dominant heterothallic reproductive modes in the genus Morchella

The MAT1–1-1 and MAT1–2-1 genes are scarcely conserved through different classes of fungi which is the main obstacle to identify sexual genes and decipher their reproductive modes in morels. Recently, the sequence of the M. eximia genome allowed the first set of MAT genes, namely MAT1–1-1 and MAT1–2-1, to be mined from fourteen black morel species in the genus Morchella and proved that the reproductive modes of these species are mainly heterothallic. However, at that time, MAT1–1-1 and MAT1–2-1 genes were not obtained from yellow morel species after multiple attempts due to the conservation of MAT genes (Du et al. 2017). To this end, based on the genome of Mes-21, we employed PCR primers designed for the most conserved domains, namely the alpha and HMG domains, of Mes-21 MAT genes, to amplify the MAT genes from twenty-two yellow morel species. Although no single ascospores were obtained from M. steppicola, Mes-24, and Mes-27, these three species are suggested to be heterothallic based on the fact that all species in the genus Morchella investigated thus far are heterothallic and that both MAT genes were obtained from their strains.

Heterothallic reproductive modes of the twenty-two species of the Esculenta Clade were supported by the evidence that amplicons specific to both MAT genes were evenly obtained by PCR from he single spores collected. Combined with the reported heterothallic reproductive modes of fourteen black morel species in the Elata Clade (Du et al. 2017), species in the genus Morchella might mainly be heterothallic. The prevalence of heterothallism as mating strategy in fungi is an important feature with implications on the genetic variability and evolutionary potential of a species (Lopes et al. 2018).

Similar to the results reported in black morel species (Du et al. 2017), ascospores of yellow morel species were shown to be haploid homokaryotic multinuclear by DAPI-staining methods under both the fluorescence microscopy and laser scanning confocal microscopy. According to the number of nuclei in the ascospores, these species could be divided into three kinds. Morchella galilaea, the widest distributed species of the Esculenta Clade had the most nuclei in ascospores among these species. It is possible that the number of ascospore nuclei might be positively correlated with the distribution range of the species, as the number of nuclei in ascospores might contribute to their vitality and spreading ability resulting in their wide distribution. However, more samples of M. galilaea and other morel species should be collected for further study and comparison.

In addition to nuclei, many mitochondria nucleoids were observed in ascospores of these yellow morel species by laser scanning confocal microscopy, similar to what was observed in other fungi by DAPI-staining (Oakley and Rinehart 1985; Chen and Butow 2005; Kucej and Butow 2007). The presence of many mitochondria nucleoids in black morels ascospores was previously shown. In fungi, mitochondrial–nuclear interactions are involved in the control of aging processes and the age-related changes in the mitochondrial DNA are proven to be part of the process leading to organismal degenerations (Osiewacz and Kimpel 1999; Osiewacz 2002). Whether the number of mitochondria nucleoids in morel ascospores would be related to morel strain degradation is not known yet and should be studied in the future.

Conflicts among the genealogies of four targeted genes and species phylogeny

In this study, we assessed the capability of gene trees from reproductive genes (MAT1–1-1 and MAT1–2-1) and non-reproductive genes (F1 and IGS) to resolve species relationships by comparing genes trees with a species phylogeny framework of the twenty-two species inferred from ITS and EF1-a combined datasets which were derived from multi-locus analyses and were previously used in studies of the genus Morchella (Taşkın et al. 2010; O’Donnell et al., 2011; Du et al. 2012, 2019b; Loizides et al. 2016; Baroni et al. 2018). One of the findings in this study is the topologies for the reproductive gene trees (mating-type) and non-reproductive genes (F1 and IGS) were in conflict with the species phylogeny framework of the Esculenta Clade. Conflicts between the gene tree genealogies and the species phylogeny could be signatures of evolutionary processes such as hybridization, introgression, gene transfer and incomplete lineage sorting (Degnan and Rosenberg 2009).

-

1.

Conflicts between reproductive genes and species trees

Individual MAT1–1-1 and MAT1–2-1 gene genealogies resolved most of the species proving their potential usefulness as phylogenetic markers for species delimitation in the Esculenta Clade (Figs. 4 and 5). Although MAT1–2-1 has previously been considered to be a better phylogenetic marker than MAT1–1-1 (Martin et al. 2010), here we found both MAT genes to be equally efficient in resolving species in the Esculenta Clade, with six species conflicting with the species phylogeny in the MAT1–1-1 genealogy and seven species in the MAT1–2-1 genealogy.

Taylor et al. (2000) proposed that conflicts among gene trees are possibly the result of recombination among individuals and that the transition from concordance to conflict determines the limits of the species. This is the principle of phylogenetic species recognition widely which is applied to fungi and specifically to Morchella. O’Donnell (2000) suggested that gene genealogy concordance is well suitable to identify hybrid individuals because hybrids should be grouped with different species in different single-gene genealogies. Several studies revealed that phylogenies of mating-type genes are in general consistent with those of other genes, such as ITS, EF1-a, Beta-tubulin and RPB2 (Turgeon 1998; Waalwijk et al. 2002; O’Donnell et al. 2004; Inderbitzin et al. 2005; Yokoyama et al. 2006; Duong et al. 2013; Du et al. 2017; Lopes et al. 2017, 2018), while other studies found they are conflicting (Wik et al. 2008; Strandberg et al. 2010).

Conflicts among genealogies of MAT1–1-1 and MAT1–2-1 and the species phylogeny indicated that some recombination or hybridization events probably occurred between Mes-20 and Mes-9. As sister species with a similar distribution area, Mes-20 and Mes-9 have the geographical advantage and potential incomplete reproductive isolation for hybridization to occur. The fact that both MAT1–1-1 and MAT1–2-1 genealogies showed the same conflicts with the species tree for Mes-20 and Mes-9 is an important finding, indicating that the two mating types likely introgressed from a single ancestral source rather than independently from different ancestors. This pattern suggested a non-random process of acquisition of the MAT alleles in the evolutionary history of the two species.

MAT genes are divergent and known to evolve quickly (Turgeon 1998). However, the MAT1–1-1 and MAT1–2-1 sequences of Mes-22 and Mes-23 samples had no differences between the two lineages, suggesting that Mes-22 and Mes-23 retained the ancestral character of interbreeding due to recent divergence. Thus, in this case, by having identical MAT gene sequences as a proxy for mating, they would in fact represent distinct phylogenetic species. Additionally, there was the possibility that incomplete lineage sorting caused the current patterns of Mes-22 and Mes-23 in the MAT1–1-1 and MAT1–2-1 genealogies. In the genealogy of MAT1–2-1, Mes-6, Mes-21 and M. dunensis formed a monophyletic group with almost identical MAT1–2-1 gene sequences. Having identical MAT gene sequences as a proxy for mating was suggested to be the ancestral character of interbreeding. Morchella clivicola, M. palazonii, and M. yangii did not form monophyletic groups in the genealogy of MAT1–1-1. In addition, either of the MAT genes genealogies, such as MAT1–2-1 for Mes-6, Mes-21, and M. dunensis, and MAT1–1-1 for M. clivicola, M. palazonii, and M. yangii, had conflicts with the species tree indicating that the two mating types independently evolved and one introgressed from different ancestors. This pattern suggested a random process of acquisition of the MAT alleles in the evolutionary history of these six species.

Unlike the phylogenies of heterothallic MAT loci shown in the Elata Clade (Du et al. 2016), the phylogeny of MAT loci in the Esculenta Clade presented here contained a few well-supported deviations from the species tree. This could be taken as evidence that lateral gene-flow existed in Esculenta Clade. Furthermore, the existence of conflicts between the phylogenies of MAT1–1-1 and MAT1–2-1 provided insights into the evolution of the Esculenta Clade and indicated that both loci evolved independently.

-

2.

Conflicts between non-reproductive genes (F1 and IGS) and the species phylogeny reveal potential hybridization

The conflicts between the genealogies of MAT genes and species phylogenies called for a further analysis of species relationship and the evolution of mating-type loci in Morchella. One way to improve the resolution of the species tree is to increase the number of loci used in the study. The F1 fragment was firstly used in the Elata Clade of the genus Morchella for population studies and some potential hybridization or gene transfer events were revealed in several species (Du et al. 2016). The phylogeny of intergenic spacer region (IGS) was reported to conflict with the phylogeny of EF1-a in the genus Fusarium (Mbofung et al. 2006; Silva et al. 2014). By comparing the reproductive (MAT1–1-1 and MAT1–2-1) and the non-reproductive (F1 and IGS) datasets, we tested whether the conflicts are inherent only to the reproductive genes or they also exist in other parts of the genome in species of the Esculenta Clade. According to the above results, the phylogenies of both F1 and IGS were shown to conflict with each other and with the species phylogeny (Figs. 6 and 7).

In F1, only five species were in consistent with the species phylogeny. Strong conflicts were detected between the genealogy of F1 and the species phylogeny in the Esculenta Clade, which were more serious than those reported in the Elata Clade (Du et al. 2016). Three samples (FCNU1062, FCNU1063, and FCNU0164) from M. galilaea generated three kinds of F1 sequences and the phylogenetic position of FCNU1064 inferred from the F1 phylogeny was clustered with samples of Mes-19. This indicated that some hybridization events might have happened between Mes-19 and M. galilaea. Hybridization processes in nature occur between pairs of taxa within a species complex (Garbelotto and Gonthier 2013). Morchella galilaea and Mes-19 are related species and both are widely distributed in China, which gives them the chance to meet in sympatry or allopatry. It is interesting to note that interspecific mating and hybridization has been reported for fungi such as Ophiostoma spp., Heterobasidion spp., Melampsora spp. and Microbotryum spp. (Chase and Ullrich 1990; Brasier et al. 1998; Newcombe et al. 2000; Gonthier et al. 2007; Gladieux et al. 2011). Hybridization occurred through secondary contact following initial divergence in allopatry for some fungi (e.g., Microbotryum) (Gladieux et al. 2011). The sample FCNU1035 from Mes-6 had the same F1 sequence as the sample FCNU 1097 from Mes-25 and they were grouped into a monophyletic group. Thus, we assume that horizontal gene transfer or hybridization events might have happened between Mes-6 and Mes-25.

In IGS, only three species were in consistent with the species phylogeny. A high degree of conflicts were shown between the genealogy of IGS and the species phylogeny. According to the species phylogeny, different kinds of IGS sequences were obtained from samples belonging to the same species. Frequent potential hybridization or horizontal gene transfer events of IGS were suggested to exist in the Esculenta Clade. When they detected conflicts between phylogenies of IGS and EF1-a in the genus Fusarium, Mbofung et al. (2006) proposed that unequal rates of evolution between loci and incomplete concerted evolution within loci could be among the factors responsible for the observed discrepancies. Most likely, these factors also contributed to the conflicts shown here.

With the increasing availability of molecular data, phylogenetic trees generated from different genes are often recognized to have conflicting branching patterns (Maddison 1997; Nichols 2001; Pamilo and Nei 1988). Davin et al. (2018) suggested that different genetic markers could yield conflicting estimates of the species phylogeny. In recent years, genome-scale sequence data have become increasingly available in phylogenetic studies for understanding the evolutionary histories of species (Liu et al. 2015). Phylogenetic analyses of genomic data revealed that different genes within a genome can have different evolutionary histories, i.e. phylogenetic conflicts (Spatafora et al. 2017; Shen et al. 2017). However, research on the sources of these conflicts, including incomplete lineage sorting, hybridization and horizontal gene transfer, as well as on the detection and characterization of these conflicts according to phylogenetic inference, is still in the early stage (Mirarab et al. 2014; Spatafora et al. 2017).

We presumed that the conflicts among the phylogenies of F1, IGS, and the species phylogeny were likely due to gene transfer and hybridization. Gene transfer is often suggested as an explanation for incongruencies between gene trees and species trees; however, although it is widely assumed to be more common in prokaryotes, it’s not considered to be a common phenomenon in eukaryotes (Dujon 2005; Syvanen 1994; Gogarten 2003; Galtier and Daubin 2008). Hybridization is now widely recognized to be an important evolutionary process which might play a crucial role in speciation (Gross and Rieseberg 2005; Mallet 2007; Schumer et al. 2014; Taylor and Larson 2019). Hybridization followed by reproductive isolation has been reported to contribute to rapid speciation of yeast (Leducq et al. 2016) and the same has been supposed to occur in some filamentous fungi (Kohn 2005; Gladieux et al. 2014; Sillo et al. 2019). Du et al. (2012) reported the 85.2% of the species in the Esculenta Clade (including almost 90% of the Chinese species lineages) diversified and went through rapid speciation in East Asia since the middle Miocene, which might have contributed to the potential hybridization and gene transfer events detected in the Esculenta Clade. Of note, we could not exclude the possibility that conflicts arising from gene trees and species phylogeny might be due to weak phylogenetic signal for F1 and IGS.

CONCLUSIONS

The results from our study showed that heterothallism is the reproductive mode in the Esculenta Clade and in the genus Morchella. The primers designed for MAT loci in the Esculenta Clade supplemented the primers previously developed for the Elata Clade (Du et al. 2017). MAT genes of the Elata Clade had similar topologies to the species phylogeny in the study of Du et al. (2017). However, the present study indicated that MAT genes of the Esculenta Clade were in conflict with species tree. Divergent evolutionary patterns were suggested for MAT genes between the Esculenta and the Elata Clades. Complex evolutionary trajectories of MAT1–1-1, MAT1–2-1, F1 and IGS in the Esculenta Clade were highlighted. Our findings contribute to a better understanding of the importance of hybridization and gene transfer in Morchella and especially for shaping reproductive modes during its evolutionary process. The genus Morchella will be useful for studying the complexities and evolution of mating types and genomes in the Ascomycota.

Availability of data and materials

Sequences generated in the present study have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers MN513618-MN513997 and MN513426-MN513494. The full alignments of these datasets were submitted to the TreeBASE (25132). The genome data of Mes-21 generated in this project has been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBankunder the accession WSNQ00000000. The version described in this paper is version WSNQ01000000.

Change history

19 May 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43008-022-00096-0

Abbreviations

- EF1-a :

-

Translation elongation factor 1-a.

- F1 :

-

Partial sequences of histone acetyltransferase ELP3.

- IGS:

-

28S–18S ribosomal intergenic spacer region.

- ITS:

-

Nuc-rDNA internal transcribed spacer region.

- MAT:

-

mating type.

References

Baroni TJ, Beug MW, Cantrell SA, Clements TA, Iturriaga T et al (2018) Four new species of Morchella from the Americas. Mycologia 110(6):1205–1221

Brasier CM, Kirk SA, Pipe ND, Buck KW (1998) Rare interspecific hybrids in natural populations of the Dutch elm disease pathogens Ophiostoma ulmi and O. novo-ulmi. Mycological Research 102:45–57

Burt A (2000) Perspective: sex, recombination, and the efficacy of selection – was Weismann right? Evolution 54:337–351

Casselton LA, Feldbrügge M (2010) Mating and sexual morphogenesis in basidiomycete fungi. In: Borkovich KA, Ebbole DJ (eds) Cellular and molecular biology of filamentous Fungi. ASM Press, USA, pp 536–555

Chase TE, Ullrich RC (1990) Genetic basis of biological species in Heterobasidion annosum: Mendelian determinants. Mycologia 82:67–72

Chen XJ, Butow RA (2005) The organization and inheritance of the mitochondrial genome. Nature Reviews Genetics 6:815–825

Coppin E, Debuchy R, Arnaise S, Picard M (1997) Mating types and sexual development in filamentous ascomycetes. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 61:411e428

Davin AA, Tannier E, Williams TA, Boussau B, Daubin V et al (2018) Gene transfers can date the tree of life. Nature Ecology & Evolution 2:904–909

Debuchy R, Berteaux-Lecellier V, Silar P (2010) Mating systems and sexual morphogenesis in Ascomycetes. In: Borkovich KA, Ebbole DJ (eds) Cellular and molecular biology of filamentous Fungi. ASM Press, USA, pp 501–536

Degnan JH, Rosenberg NA (2009) Gene tree discordance, phylogenetic inference and the multispecies coalescent. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 24:332–340

Du XH, Wang HC, Sun JJ, Xiong LY, Yu JJ (2019a) Hybridization, characterization and transferability of SSRs in the genus Morchella. Fungal Biology 123:528–538

Du XH, Wu DM, He GQ, Wei W, Xu N et al (2019b) Six new species and two new records of Morchella in China using phylogenetic and morphological analyses. Mycologia. https://doi.org/10.1080/00275514.2019.1640012

Du XH, Zhao Q, O’Donnell K, Rooney AP, Yang ZL (2012) Multigene molecular phylogenetics reveals true morels (Morchella) are especially species-rich in China. Fungal Genetics and Biology 49:455–469

Du XH, Zhao Q, Xia EH, Gao LZ, Richard F et al (2017) Mixed reproductive strategies, competitive mating-type distribution and life cycle of fourteen black morel species. Scientific Reports 7:1493

Du XH, Zhao Q, Xu J, Yang ZL (2016) High inbreeding, limited recombination and divergent evolutionary patterns between two sympatric morel species in China. Scientific Reports 6:22434

Dujon B (2005) Hemiascomycetous yeasts at the forefront of comparative genomics. Curr Opin Gen 15:614–620

Duong TA, De Beer ZW, Wingfield BD, Wingfield MJ (2013) Characterization of the mating-type genes in Leptographium procerum and Leptographium profanum. Fungal Biology 117:411–421

Fraser JA, Hsueh YP, Findley KM, Heitman J (2007) Evolution of the mating-type locus: the basidiomycetes. In: Heitman J, Kronstad JW, Taylor JW, Casselton LA (eds) Sex in fungi: molecular determination and evolutionary implications. ASM Press, USA, pp 19–34

Galtier N, Daubin V (2008) Dealing with incongruence in phylogenomic analyses. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 363:4023–4029

Garbelotto M, Gonthier P (2013) Biology, epidemiology, and control of heterobasidion species worldwide. Annual Review of Phytopathology 51:39–59

Gioti A, Mushegian AA, Strandberg R, Stajich JE, Johannesson H (2012) Unidirectional evolutionary transitions in fungal mating systems and the role of transposable elements. Molecular Biology and Evolution 29:3215–3226

Gladieux P, Ropars J, Badouin H, Branca A, Aguileta G et al (2014) Fungal evolutionary genomics provides insight into the mechanisms of adaptive divergence in eukaryotes. Molecular Ecology 23:753–773

Gladieux P, Vercken E, Fontaine MC, Hood ME, Jonot O et al (2011) Maintenance of fungal pathogen species that are specialized to different hosts: allopatric divergence and introgression through secondary contact. Molecular Biology and Evolution 28:459–471

Gogarten JP (2003) Gene transfer: gene swapping craze reaches eukaryotes. Current Biology 13:53–54

Gonthier P, Nicolotti G, Linzer R, Guglielmo F, Garbellotto M (2007) Invasion of European pine stands by a north American forest pathogen and its hybridization with a native interfertile taxon. Molecular Ecology 16:1389–1400

Groenewald M, Barnes I, Bradshaw RE, Brown AV, Dlae A et al (2007) Characterization and distribution of mating type genes in the Dothistroma needle blight pathogens. Mycology 97(7):825–834

Groenewald M, Groenewald JZ, Harrington TC, Abeln ECA, Crous PW (2006) Mating type gene analysis in apparently asexual Cercospora species is suggestive of cryptic sex. Fungal Genetics and Biology 43:813e825

Gross BL, Rieseberg LH (2005) The ecological genetics of homoploid hybrid speciation. Journal of Heredity 96:241–252

Heitman J (2015) Evolution of sexual reproduction: a view from the fungal kingdom supports an evolutionary epoch with sex before sexes. Fungal Biology Reviews 3:108–117

Inderbitzin P, Harkness J, Turgeon BG, Berbee ML (2005) Lateral transfer of mating system in Stemphylium. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102:11390–11395

Katoh K, Misawa K, Kuma K, Miyata T (2002) MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Research 30:3059–3066

Kauserud H, Schumacher T (2001) Outcrossing or inbreeding: DNA markers provide evidence for type of reproductive mode in Phellinus nigrolimitatus (Basidiomycota). Mycological Research 105:676–683

Kohn LM (2005) Mechanisms of fungal speciation. Ann Rev Pytopathology 43:279–308

Kronstad JW, Staben C (1997) Mating types in filamentous fungi. Annual Review of Genetics 31:245–276

Kucej M, Butow RA (2007) Evolutionary tinkering with mitochondrial nucleoids. Trends in Cell Biology 17(12):586–592

Kuo M, Dewsbury DR, O’Donnell K, Carter MC, Rehner SA et al (2012) Taxonomic revision of true morels (Morchella) in Canada and the United States. Mycologia 104:1159–1177

Leducq JB, Nielly-Thibault L, Charron G, Eberlein C, Verta JP et al (2016) Speciation driven by hybridization and chromosomal plasticity in a wild yeast. Nature Microbiology 1:15003

Lee SC, Ni M, Li W, Shertz C, Heitman J (2010) The evolution of sex: a perspective from the fungal kingdom. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 74:298e340

Liu L, Wu SY, Yu LL (2015) Coalescent methods for estimating species trees from phylogenomic data. Journal of Systematics and Evolution 53(5):380–390

Loizides M, Bellanger JM, Clowez P, Richard F, Moreau PA (2016) Combined phylogenetic and morphological studies of true morels (Pezizales, Ascomycota) in Cyprus reveal significant diversity, including Morchella arbutiphila and M. disparilis spp. nov. mycological Progress 15: 39

Lopes A, Linaldeddu BT, Phillips ALJ, Alves A (2018) Mating type gene analyses in the genus Diplodia: from cryptic sex to cryptic species. Fungal Biology 122:629–638

Lopes A, Phillips AJL, Alves A (2017) Mating type genes in the genus Neofusicoccum: mating strategies and usefulness in species delimitation. Fungal Biology 121:394e404

Maddison WP (1997) Gene trees in species trees. Systematic Biology 46:523e536

Mallet J (2007) Hybrid speciation. Nature 446:279

Martin SH, Steenkamp ET, Wingfield MJ, Wingfield BD (2013) Mate-recognition and species boundaries in the ascomycetes. Fungal Diversity 58:1e12

Martin T, Lu SW, van Tilbeurgh H, Ripoll DR, Christina D et al (2010) Tracing the origin of the fungala1 domain places its ancestor in the HMG-box superfamily: implication for fungal mating-type evolution. PLoS One 5:e15199

Mbofung GY, Hong SG, Pryor BM (2006) Phylogeny of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lactucae inferred from mitochondrial small subunit, elongation factor 1-α, and nuclear ribosomal intergenic spacer sequence data. Phytopathology 97:87–98

Metzenberg RL, Glass NL (1990) Mating type and mating strategies in Neurospora. Bioessays 12:53–59

Mirarab S, Bayzid MS, Boussau B, Warnow T (2014) Statistical binning enables an accurate coalescent based estimation of the avian tree. Science 346:1250463–1250463

Newcombe G, Stirling B, McDonald S, Bradshaw HD (2000) Melampsora columbiana, a natural hybrid of M. medusae and M. occidentalis. Mycological Research 104:261–274

Nichols R (2001) Gene trees and species trees are not the same. Trends Ecol Evol 16:358–364

O’Donnell K (2000) Molecular phylogeny of the Nectria haematococca-Fusarium solani species complex. Mycologia 92:919–938

O’Donnell K, Rooney AP, Mills GL, Kuo M, Weber NS et al (2011) Phylogeny and historical biogeography of true morels (Morchella) reveals an early cretaceous origin and high continental endemism and provincialism in the Holarctic. Fungal Genetics and Biology 48:252–265

Oakley BR, Rinehart JE (1985) Mitochondria and nuclei move by different mechanisms in Aspergillus nidulans. The Journal of Cell Biology 101:2392–2397

O'Donnell K, Ward TJ, Geiser DM, Kistler HC, Aoki T (2004) Genealogical concordance between the mating type locus and seven other genes supports formal recognition of nine phylogenetically distinct species within the Fusarium graminearum clade. Fungal Genetics and Biology 41:600e623

Osiewacz HD (2002) Aging in fungi: role of mitochondria in Podospora anserina. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development 123:755–764

Osiewacz HD, Kimpel E (1999) Mitochondrial-nuclear interactions and lifespan control in fungi. Experimental Gerontology 34:901–909

Palumbi SR (2009) Speciation and the evolution of gamete recognition genes: pattern and process. Heredity 102:66–76

Pamilo P, Nei M (1988) Relationships between gene trees and species trees. Molecular Biology and Evolution 5:568–583

Paoletti M, Buck KW, Brasier CM (2006) Selective acquisition of novel mating type and vegetative incompatibility genes via interspecies gene transfer in the globally invading eukaryote Ophiostoma novo-ulmi. Molecular Ecology 15:249–262

Rambaut A (2009) FigTree version:1.4.2 Available at http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/

Schumer M, Rosenthal GG, Andolfatto P (2014) How common is homoploid hybrid speciation? Evolution 68:1553–1560

Shen XX, Hittinger CT, Rokas A (2017) Contentious relationships in phylogenomic studies can be driven by a handful of genes. Nat Ecol Evol 1(5):126

Sillo F, Gonthier P, Lockman B, Kasuga T, Garbelotto M (2019) Molecular analyses identify hybridization-mediated nuclear evolution in newly discovered fungal hybrids. Ecology and Evolution 00:1–18

Silva FPD, Vechiato MH, Harakava R (2014) EF-1α gene and IGS rDNA sequencing of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. Vasinfectum and F. oxysporum f. sp. phaseoli reveals polyphyletic origin of strains. Tropical Plant Pathology 39(1):064–073

Spatafora JW, Aime MC, Grigoriev IV, Martin F, Stajich JE et al (2017) The fungal tree of life: from molecular systematics to genome-scale phylogenies. Microbiology Spectrum 5:3–34

Stamatakis A (2006) RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 22:2688–2690

Strandberg R, Nygren K, Menkis A, James TY, Wik L et al (2010) Conflict between reproductive gene trees and species phylogeny among heterothallic and pseudohomothallic members of the filamentous ascomycete genus Neurospora. Fungal Genetics and Biology 47:869e878

Sun S, Heitman J (2015) From two to one: unipolar sexual reproduction. Fungal Biology Reviews 29:118e125

Swanson WJ, Vacquier VD (2002) The rapid evolution of reproductive proteins. Nature Reviews Genetics 3:137–144

Swofford, D.L. PAUP* (2002) Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (*and other methods). Version 4

Syvanen M (1994) Horizontal gene transfer: evidence and possible consequences. Annual Review of Genetics 28:237–261

Taşkın H, Büyükalaca S, Doğan HH, Rehner SA, O’Donnell K (2010) A multigene molecular phylogenetic assessment of true morels (Morchella) in Turkey. Fungal Genetic and Biology 47:672–682

Taylor JW, Jacobson DJ, Kroken S, Kasuga T, Geiser DM et al (2000) Phylogenetic species recognition and species concepts in fungi. Fungal Genetics and Biology 31:21e32

Taylor SA, Larson EL (2019) Insights from genomes into the evolutionary importance and prevalence of hybridization in nature. Nat Ecol Evol 3:170

Turgeon BG (1998) Application of mating type gene technology to problems in fungal biology. Annual Review of Phytopathology 36:115–137

Waalwijk C, Mendes O, Verstappen ECP, Warrd MAD, Kema GHJ (2002) Isolation and characterization of the mating-type idiomorphs from the wheat septoria leaf blotch fungus Mycosphaerella graminicola. Fungal Genetics and Biology 35:277–286

Walters JR, Harrison RG (2008) EST analysis of male accessory glands from Heliconius butterflies with divergent mating systems. BMC Genomics 9:592

White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, Taylor J (1990) Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis MA, Gelfand HH, Sninsky JJ, White TJ (eds) PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications. Academic Press, USA, pp 315–322

Wik L, Karlsson M, Johannesson H (2008) The evolutionary trajectory of the mating-type (mat) genes in Neurospora relates to reproductive behavior of taxa. BMC Evolutionary Biology 8:109

Yokoyama E, Arakawa M, Yamagishi K, Hara A (2006) Phylogenetic and structural analyses of the mating-type loci in Clavicipitaceae. FEMS Microbiology Letters 264:182e191

Zerbino DR, Birney E (2008) Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Research 18:821–829

Zhan J, Torriani SFF, McDonald BA (2007) Significant difference in pathogenicity between MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 isolates in the wheat pathogen Mycosphaerella graminicola. Fungal Genetics and Biology 44:339–346

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Zhu L. Yang and Hong Luo (Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Science), Jianping Xu (Department of Biology, McMaster University), Kerry O’Donnell (Bacterial Foodborne Pathogens and Mycology Research Unit, National Center for Agricultural Utilization), Hanma Zhang and Bo Li (Chongqing Normal University), Franck Richard and Jean-Michel Bellanger (Centre d’Ecologie Fonctionnelle et Evolutive, CNRS), for kind help during the study. Yu Liu and Jianrui Wang (Ludong University), Xinsheng He (Southwest University of Science and Technology), Hao Hu, Bei Xiao, Xue-Feng Jia (Biotechnology Research Institute, Xinjiang Agricultural Reclamation Academy of Sciences), and many other kind people are acknowledged for their help during collecting samples and the authors’ field trip. Nan Xu, Chao Zhou, Dan Kuang and Lu Liu (Chongqing Normal University) are acknowledged for excellent technical assistance. Many thanks also are due to the anonymous reviewers for constructive comments and suggestions.

Adherence to national and international regulations

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by Scientific and Technological Research Program of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission (No. KJ1703052), Chongqing basic science and frontier research project (No. cstc2017jcyjAX0179) and Chongqing Natural Science Foundation (No. cstc2018jcyjA3693). The funders had no role in study design, interpretation of data or the preparation of the present manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xi-Hui Du designed the study. Xi-Hui Du, Dongmei Wu, Heng Kang, Hanchen Wang, Nan Xu, Tingting Li and Keliang Chen collected the samples and conducted the laboratory work. Xi-Hui Du analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This work conforms with all regulations pertaining to ethics approval and the consent to participate. In general, this is not applicable to our study, as there were no human subjects subject to research.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: Following the publication of the original article, we were notified of two mistaken pairs of primer sequences in Table 2.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Du, XH., Wu, D., Kang, H. et al. Heterothallism and potential hybridization events inferred for twenty-two yellow morel species. IMA Fungus 11, 4 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43008-020-0027-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43008-020-0027-1