Abstract

Background

Artificial intelligence (AI) uses computer systems to simulate cognitive capacities to accomplish goals like problem-solving and decision-making. Machine learning (ML), a branch of AI, makes algorithms find connections between preset variables, thereby producing prediction models. ML can aid shoulder surgeons in determining which patients may be susceptible to worse outcomes and complications following shoulder arthroplasty (SA) and align patient expectations following SA. However, limited literature is available on ML utilization in total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) and reverse TSA.

Methods

A systematic literature review in accordance with PRISMA guidelines was performed to identify primary research articles evaluating ML’s ability to predict SA outcomes. With duplicates removed, the initial query yielded 327 articles, and after applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, 12 articles that had at least 1 month follow-up time were included.

Results

ML can predict 30-day postoperative complications with a 90% accuracy, postoperative range of motion with a higher-than-85% accuracy, and clinical improvement in patient-reported outcome measures above minimal clinically important differences with a 93%–99% accuracy. ML can predict length of stay, operative time, discharge disposition, and hospitalization costs.

Conclusion

ML can accurately predict outcomes and complications following SA and healthcare utilization. Outcomes are highly dependent on the type of algorithms used, data input, and features selected for the model.

Level of Evidence

III

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) utilizes computer systems to simulate cognitive capacities to accomplish goals such as problem-solving and decision-making [1, 2]. A branch of AI known as machine learning (ML) creates algorithms to find connections between preset variables, which are then used to produce prediction models. Algorithms are collections of mathematical processes that explain how variables relate to one another. Algorithms start with data input and work through a set of pre-defined instructions to produce an output [3, 4]. The models are continually improved by using new data, which ultimately refines the prediction ability of the models with little human involvement [5, 6]. There are two types of ML: supervised and unsupervised. Supervised ML is utilized most frequently in healthcare and involves “training” or inputting a dataset of variables, known as features, with their relevant outcomes [7]. This allows the computer algorithm to find patterns and associations between features and certain outcomes [7]. After training is completed, the algorithm goes through a “testing” phase where the features of a dataset are applied to the algorithm. The predictions are then compared with known outcomes to determine the algorithm’s accuracy and performance [7]. Unsupervised ML is a data mining method that is used to detect unknown patterns in data without requiring prior human knowledge and intervention [8]. This form of machine learning is typically used more in an exploratory manner without yielding absolute conclusions because the output is highly dependent on whatever parameters are input.

In various prediction problems, ML techniques have demonstrated the ability to outperform conventional approaches such as regression techniques [9, 10]. ML is currently being used more commonly in the field of orthopedic surgery for outcome prediction, diagnostics, and cost-efficiency analyses [3, 11, 12]. ML has been utilized in both total hip and knee arthroplasty to predict patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) as well as hospital utilization [13,14,15,16,17,18]. However, there is limited literature available on the utilization of ML in shoulder arthroplasty (SA). The use of anatomic total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) in the United States has continued to climb due to an aging population as well as expanded indications for reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (rTSA), as seen by a 9.4% yearly increase in procedure volume [19]. Several modifiable and non-modifiable patient characteristics, such as body mass index (BMI), smoking status, or age, increase the risk of complications following SA [20, 21]. Additionally, several studies have shown promise in using ML to predict clinical outcomes such as range of motion (ROM) and PROMs. For instance, Kumar et al., demonstrated ML could predict measures of pain, function, and ROM with an 85 to 94 percent accuracy following TSA [22]. Similarly, Saiki et al., reported that the random forest model algorithm could be useful in predicting knee flexion ROM following TKA [23]. Therefore, the use of ML can aid the shoulder surgeon in determining which patients may be susceptible to complications or poor outcomes following shoulder arthroplasty and can help align patient expectations following TSA and rTSA.

The purpose of this systematic review was to evaluate whether machine learning can be used to predict TSA and rTSA outcomes. Specifically, we asked: (1) Is machine learning able to accurately predict the outcomes and complications after SA? (2) Is machine learning able to accurately predict healthcare utilization including discharge disposition after SA?

Methods

Search strategy and criteria

The PubMed, EBSCO host, and Google Scholar electronic databases were searched to identify all studies that evaluated the ability of ML to predict the outcomes of SA. The following keywords were utilized in combination with “AND” or “OR” Boolean operators: (“machine learning” OR “ML” OR “AI” OR “Artificial intelligence” OR “deep learning”) AND (“shoulder arthroplasty” OR “TSA” OR “shoulder surgery” OR “shoulder replacement”).

Eligibility criteria

For inclusion in this systematic review, each study had to meet the following criteria: (1) articles were currently published, (2) articles reported on the accuracy of ML to predict outcomes of SA, (3) studies were written in the English language. Studies were excluded if they (1) were systematic reviews, (2) were non-peer-reviewed journal publications, case reports, case series, or letters to the editor, (3) provided no relevant outcomes or no outcomes data, (4) were articles that were not given full-text access, (5) or were publications in languages other than English.

Study selection

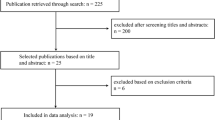

In accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines, two reviewers (A.K. and J.L.) independently assessed the eligibility of each article to be included in our review [24]. Any differences between the investigators were handled through discussion until a consensus was reached. The initial query yielded 327 publications, which were then screened for appropriate studies that aligned with the purpose of our review. After the removal of duplicates and reading each abstract, 16 studies were selected for further consideration. The full text of each article was then reviewed, of which 12 fulfilled our inclusion and exclusion criteria. A comprehensive examination of each study’s reference list yielded no further papers. Figure 1 depicts the selection procedure.

Data extraction and collection

A collaborative online spreadsheet (Google Sheets), arranged by two reviewers prior to starting, facilitated data extraction. Two independent reviewers (A.K. and J.L.) extracted the data through a manual full-text review with an identical review strategy. Any disagreements among the investigators were resolved via conversation until consensus was attained. Name of authors, year of publication, study design, sample size, and age (mean), the algorithm used, number of features used, and any relevant outcome reported were extracted from the articles.

Assessment of methodological quality

The Methodological Index for Non-randomized Studies (MINORS) tool was used by the two reviewers (A.K. and J.L.) to independently evaluate the methodological quality and internal and external validity of all included studies [25]. Twelve evaluation criteria are included in MINORS, of which the first eight are relevant to non-comparative studies with four additional items applicable to comparative studies. A score of 0 (not reported), 1 (reported but inadequate), or 2 is assigned to each item (reported and adequate). For non-comparative studies, the maximum score is 16, and for comparative studies, the maximum score is 24, with higher values indicating higher study quality.

Data synthesis

A meta-analysis was not carried out due to the heterogeneity of ML algorithms, the presentation of the data, and the outcomes studied. Due to the absence of distinct data, analyses by age groups and gender were also not possible. For each study and result, all the data were gathered and were narratively described.

Primary and secondary study outcomes

Our primary study goal was to determine the ability of machine learning to predict the outcomes of SA. Of the included studies, nine studies evaluated the accuracy of machine learning to predict SA outcomes. These studies reported PROMs, 30-day complications, and clinical outcomes such as shoulder ROM (with some reporting mean absolute error [MAE]). The secondary objective was to ascertain whether machine learning is capable of forecasting healthcare utilization for SA and the number and type of features that can be used to accurately make predictions. Four studies evaluated either length of stay (LOS), operative time, discharge disposition, or hospitalization costs.

Results

Included studies

The final analysis included 12 studies involving 201,649 patients with an average mean age of 65.2 ± 8.23 years (Table 1) [22, 26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. There were 43.1% males (86,985) and 56.9% females (114,664). All of the studies were of retrospective design, with an average MINOR score of 14.33 ± 0.78. Five studies used national databases, four of which used the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP); one used the National Inpatient Sample (NIS database); five studies used a multicenter database, and two studies used data from a single institution. Five studies evaluated both rTSA and aTSA separately, while the other six studies did not distinguish between the two. There were 13 different ML algorithms used in the study, including Logistic Regression, K-Nearest Neighbor, Random Forest, Naive-Bayes, Decision Tree, Gradient Boosting Trees, Artificial Neural Network, Linear Regression, XGBoost, Wide and Deep, Stochastic Gradient Boosting, Support Vector Machine, and Elastic-Net Penalized Logistic Regression.

Machine learning and SA outcomes

Nine of the twelve studies agreed that ML could predict the outcomes of SA (Table 2) [22, 27, 29,30,31, 33,34,35,36]. Three studies reported that ML could predict 30-day postoperative complications, with one also advocating for the ability of ML to predict any adverse event, transfusion, extended length of stay, surgical site infection, reoperation, and readmission [27, 33, 34].

ML was also able to predict ROM at different postoperative time points. Kumar et al., in two different studies, reported that machine learning (Wide and Deep and XG Boost) could predict postoperative ROM, with a mean absolute error (MAE) between ± 18° to 21.8° for active abduction, ± 15° to 19.2° for forward flexion and ± 10° to 12.6° for external rotation [22, 31]. Both studies ran independent models for TSA and rTSA cases as well, finding similar predictability between both. Similarly, in a different study, Kumar et al. showed that machine learning could predict postoperative minimal clinically important difference (MCID) internal rotation with a 90% accuracy for anatomic TSA and an 85% accuracy for rTSA [30]. Five articles demonstrated that ML could accurately predict PROMs [22, 29, 31, 35, 36]. Kumar et al. were able to identify patients undergoing either TSA or rTSA that would have PROM improvement exceeding the MCID in multiple studies [22, 29, 31], while McLendon et al. demonstrated that ML could predict the degree of improvement in ASES scores by around 95% [35].

Machine learning and healthcare utilization for SA

The four studies on LOS, operative time, discharge disposition, or hospitalization costs were in agreement regarding ML ability to predict different aspects of healthcare (Table 3) [26, 28, 33, 34]. Two studies reported that ML could accurately predict LOS of patients, with one study reporting accurate disposition for patients remaining hospitalized ≤ 1 day or > 3 days following SA [26]. Karnuta et al. were able to predict length of stay with an accuracy of 79.1% for acute or traumatic conditions for their inpatient admission and 91.8% for chronic or degenerative conditions [28]. Lopez et al. were able to predict operative time with 85% accuracy [34]. The authors also used two different ML algorithms to predict non-home discharge with an accuracy greater than 90% [33]. Using a different algorithm, Karnuta et al. were able to predict disposition to home with an accuracy of 70% [28]. They also predicted total inpatient costs after SA with an accuracy of 70.3% for acute conditions and 76.5% for chronic conditions [26].

Machine learning and features

Six of the articles reported on the number and type of features required for ML to make any of the above predictions (Table 4) [29,30,31,32, 35, 36]. In three different studies, Kumar et al. demonstrated that utilizing the minimal-feature model (19 features) had comparable accuracy as compared to using the full-feature model (291 features) in predicting ROM and PROMs for either TSA or rTSA (Table 5) [29,30,31]. Additionally, they discovered that only slight improvements in MAEs were observed for each outcome measure when the minimal model was supplemented with information on implant size and/or type as well as measurements of native glenoid anatomy [29, 30]. In all of their studies, Kumar et al. showed that the presence of radiographical information does not provide significant predictive ability to ML algorithms [29,30,31]. Follow-up duration and composite ROM were the most important or predictive features for the full-feature model and the minimal-feature model, respectively [27, 29].

Polce et al. were able to accurately predict patient satisfaction based on 16 features. For the support vector machine algorithm, they found the five most predictive variables to predict patient satisfaction were baseline SANE score, exercise and activity, insurance status, diagnosis, and preoperative duration of symptoms [36]. In two different studies, Kumar et al. reported on the best predictors of postoperative outcomes, citing preoperative Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI) scores, postoperative SAS scores, ASES, UCLA, and Constant scores overall as the most predictive [29, 32]. Finally, McLendon et al. demonstrated that both the preoperative ASES and morphological variables of the shoulder were required in combination to accurately predict the improvement in ASES scores [35].

Discussion

All 12 articles were consistent in reporting that machine learning could accurately predict outcomes and complications after SA. ML also seems to be successful at predicting post-SA PROMs. While ASES was the most common outcome score predicted, there was a high variability in outcomes tested and predicted among studies. Multiple studies also focused on predicting improvement greater than established PROM MCIDs [22, 29, 35]. This level allows for increased standardization and clinical conclusions from the data and should be used in future studies as well.

Lopez et al. and Gowd et al. both validated the ability of their ML algorithms to predict complications, while Gowd et al. also noted that their algorithm outperformed comorbidity indices-alone models [27, 33, 34]. This is similar to results seen in both hip and knee arthroplasty. For instance, Harris et al. demonstrated that neural network models had good accuracy in determining the likelihood a patient would experience renal or cardiac complications [15]. The ability of ML to predict outcomes can help with surgical risk classification and enable surgeons to use measures to lower complications and improve outcomes.

In addition to outcome prediction following SA, ML was able to predict different healthcare utilization factors such as LOS and discharge disposition with high accuracy and reliability. This is a valuable tool that may help lower healthcare-related costs. Calkins et al. reported that outpatient SA led to a charge reduction of $25,509 to $53,202 per patient compared to inpatient SA, and this data can be used preoperatively for patient disposition planning [37]. Additionally, disposition planning to non-home facilities is commonly delayed, resulting in extended hospital LOS, higher expenses, and increased patient morbidity and mortality [38,39,40]. By using ML to predict which patients would be discharged to non-home facilities, surgeons may organize ahead of time to accelerate the discharge process, which may lower healthcare-related costs and potentially mitigate adverse events.

Although ML in clinical use is promising, the accuracy of prediction is highly sensitive to the algorithm used and the number and type of features chosen as input values. Kumar et al. were able to demonstrate accurate PROMs following SA using as little as 19 features [29,30,31]. The authors found that the SAS score, which is a composite of ASES sub-questions, was one of the most accurate features. Unfortunately, there is no consensus on the type or amount of features that most accurately predict outcomes among a wide variety of patients. There were 13 different algorithms used across studies, all of them showing relatively strong predictive ability. While increasing features logically seems to add granularity and detail to predictive algorithms, it also adds an element of complexity that may not be easily reproducible or clinically significant. As more algorithms are created and validated, the most efficient and generalizable algorithm will hopefully be elucidated. However, currently, there does not seem to be a specific algorithm that is significantly superior to other types of algorithms. In our study, seven articles utilized multiple algorithms for their studies and demonstrated similar accuracy between the algorithms used.

In addition, only four studies ran independent models for TSA and rTSA cases [22, 29,30,31]. Karnuta et al. was the only other study that separated TSA and rTSA cases [28]. The other studies either pool all cases together or do not differentiate which types of shoulder replacements they use. Furthermore, there is some inconsistency among the included articles about how shoulder arthroplasty is referred to (TSA denoting all shoulder arthroplasties versus denoting only anatomic total shoulder arthroplasties). Having a clear delineation of which procedures are being included as well as separate models for TSA and rTSA cases is important for all future ML studies to do. The two procedures, including technical factors as well as patient selection, are very different. Factors that lead to successful outcomes are also very different in both procedures, highlighting the need for independent modeling. Even though the limited available studies had similar predictability for all modeled outcomes for both TSA and rTSA models, this needs to be further studied (and statistically compared, which was not done in our review) to definitively determine whether one model can accurately predict both types of procedures as one cohort.

Finally, many studies only tested their algorithms at one center with one patient population. Testing their algorithms among multiple centers and patient populations strengthens the algorithm’s ability to accurately predict outcomes in a wider variety of populations, increasing its generalizability to all patient types. Furthermore, all 12 studies were internally validated. It is also important to externally validate these algorithms, given the propensity for ML algorithms to over-fit data that it has been exposed to and under-fit data it has not yet been exposed to. External validations will help increase trust and adoption of these new tools. However, these points highlight the importance of further testing of ML algorithms to not only determine a universal algorithm that is used consistently across the country but also to determine the set of features that allows for accurate predictions using differing algorithms. In a systematic review of the availability of externally validated ML models with orthopedic outcomes, Groot et al. reported that only 10/50 of the ML models predicting orthopedic surgical outcomes were externally validated, but those that had good discrimination ability [41]. Despite the crucial need to evaluate prediction models on new datasets, this is seldom done due to data protection by institutions and journal preferences for publishing developmental studies. Algorithms with poor external validation performance may face publication bias.

Limitations

Our analysis has several limitations. Firstly, all the included studies in our analysis had a retrospective design, which limits the capability to accurately determine the ability of machine learning to predict outcomes of SA prospectively. Secondly, there was heterogeneity across the studies regarding the type of algorithms used and the number of features used to train the algorithm, and the outcomes they studied. However, this may allow for improved generalizability of our results as there are frequently incomplete patient data depending on the algorithm used. Thirdly, five of the studies included were by Kumar et al., which limits the generalizability of the study. However, they used a multicenter database, which contained a large composite of patient information from multiple institutions, thus increasing the generalizability of the study. Despite these limitations, our systematic review provides the first summary of the available literature on the ability of machine learning to predict the outcomes of shoulder arthroplasty and healthcare utilization.

Conclusion

Our systematic review found that machine learning could accurately predict both ROM and PROMs, complications, and healthcare utilization of patients undergoing TSA and rTSA. These findings encourage continued efforts to utilize both machine learning and other technology to improve patient outcomes of shoulder arthroplasty. Efforts should focus on determining which patients are at risk of poor outcomes following shoulder arthroplasty and potential ways to mitigate these risks preoperatively and provide the patient with appropriate preoperative counseling to enhance shared decision-making. With multiple machine learning algorithms being utilized in the current literature, future studies should establish a consistent algorithm to ensure patients who are at an increased risk for complication are reliably identified to receive optimal treatment.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Ghahramani Z. Probabilistic machine learning and artificial intelligence. Nature. 2015;521:452–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14541.

Obermeyer Z, Emanuel EJ. Predicting the future - big data, machine learning, and clinical medicine. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1216–9. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1606181.

Ramkumar PN, Navarro SM, Haeberle HS, et al. Development and validation of a machine learning algorithm after primary total hip arthroplasty: applications to length of stay and payment models. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34:632–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2018.12.030.

Rowe M. An introduction to machine learning for clinicians. Acad Med. 2019;94:1433–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002792.

Deo RC. Machine learning in medicine. Circulation. 2015;132:1920–30. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.001593.

Awan SE, Sohel F, Sanfilippo FM, et al. Machine learning in heart failure: ready for prime time. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2018;33:190–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/HCO.0000000000000491.

Sidey-Gibbons JAM, Sidey-Gibbons CJ. Machine learning in medicine: a practical introduction. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19:64. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0681-4.

Ramsdale E, Snyder E, Culakova E, et al. An introduction to machine learning for clinicians: how can machine learning augment knowledge in geriatric oncology? J Geriatr Oncol. 2021;12:1159–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2021.03.012.

Senders JT, Arnaout O, Karhade AV, et al. Natural and artificial intelligence in neurosurgery: a systematic review. Neurosurgery. 2018;83:181–92. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuros/nyx384.

Azimi P, Benzel EC, Shahzadi S, et al. The prediction of successful surgery outcome in lumbar disc herniation based on artificial neural networks. J Neurosurg Sci. 2016;60:173–7.

Chung SW, Han SS, Lee JW, et al. Automated detection and classification of the proximal humerus fracture by using deep learning algorithm. Acta Orthop. 2018;89:468–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2018.1453714.

Kalagara S, Eltorai AEM, Durand WM, et al. Machine learning modeling for predicting hospital readmission following lumbar laminectomy. J Neurosurg Spine. 2018;30:344–52. https://doi.org/10.3171/2018.8.SPINE1869.

Fontana MA, Lyman S, Sarker GK, et al. Can machine learning algorithms predict which patients will achieve minimally clinically important differences from total joint arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2019;477:1267–79. https://doi.org/10.1097/CORR.0000000000000687.

Cai X, Perez-Concha O, Coiera E, et al. Real-time prediction of mortality, readmission, and length of stay using electronic health record data. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23:553–61. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocv110.

Harris AHS, Kuo AC, Bowe TR, et al. Can machine learning methods produce accurate and easy-to-use preoperative prediction models of one-year improvements in pain and functioning after knee arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty. 2021;36:112-117.e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2020.07.026.

Huber M, Kurz C, Leidl R. Predicting patient-reported outcomes following hip and knee replacement surgery using supervised machine learning. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2019;19:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-018-0731-6.

Kunze KN, Karhade AV, Sadauskas AJ, et al. Development of machine learning algorithms to predict clinically meaningful improvement for the patient-reported health state after total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35:2119–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2020.03.019.

Navarro SM, Wang EY, Haeberle HS, et al. Machine learning and primary total knee arthroplasty: patient forecasting for a patient-specific payment model. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:3617–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2018.08.028.

Day JS, Lau E, Ong KL, et al. Prevalence and projections of total shoulder and elbow arthroplasty in the United States to 2015. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19:1115–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2010.02.009.

Jiang JJ, Toor AS, Shi LL, Koh JL. Analysis of perioperative complications in patients after total shoulder arthroplasty and reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23:1852–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2014.04.008.

Leschinger T, Raiss P, Loew M, Zeifang F. Total shoulder arthroplasty: risk factors for intraoperative and postoperative complications in patients with primary arthritis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26:e71–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2016.08.001.

Kumar V, Roche C, Overman S, et al. What is the accuracy of three different machine learning techniques to predict clinical outcomes after shoulder arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2020;478:2351–63. https://doi.org/10.1097/CORR.0000000000001263.

Saiki Y, Kabata T, Ojima T, et al. Machine learning algorithm to predict worsening of flexion range of motion after total knee arthroplasty. Arthroplast Today. 2022;17:66–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artd.2022.07.011.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, et al. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73:712–6. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1445-2197.2003.02748.x.

Biron DR, Sinha I, Kleiner JE, et al. A novel machine learning model developed to assist in patient selection for outpatient total shoulder arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020;28:e580–5. https://doi.org/10.5435/JAAOS-D-19-00395.

Gowd AK, Agarwalla A, Amin NH, et al. Construct validation of machine learning in the prediction of short-term postoperative complications following total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2019;28:e410–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2019.05.017.

Karnuta JM, Churchill JL, Haeberle HS, et al. The value of artificial neural networks for predicting length of stay, discharge disposition, and inpatient costs after anatomic and reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2020;29:2385–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2020.04.009.

Kumar V, Allen C, Overman S, et al. Development of a predictive model for a machine learning–derived shoulder arthroplasty clinical outcome score. Seminars in Arthroplasty: JSES. 2022;32:226–37. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.sart.2021.09.005.

Kumar V, Schoch BS, Allen C, et al. Using machine learning to predict internal rotation after anatomic and reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2022;31:e234–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2021.10.032.

Kumar V, Roche C, Overman S, et al. Using machine learning to predict clinical outcomes after shoulder arthroplasty with a minimal feature set. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2021;30:e225–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2020.07.042.

Kumar V, Roche C, Overman S, et al. Use of machine learning to assess the predictive value of 3 commonly used clinical measures to quantify outcomes after total shoulder arthroplasty. Seminars in Arthroplasty: JSES. 2021;31:263–71. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.sart.2020.12.003.

Lopez CD, Constant M, Anderson MJJ, et al. Using machine learning methods to predict nonhome discharge after elective total shoulder arthroplasty. JSES Int. 2021;5:692–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jseint.2021.02.011.

Lopez CD, Constant M, Anderson MJJ, et al. Using machine learning methods to predict prolonged operative time in elective total shoulder arthroplasty. Seminars in Arthroplasty: JSES. 2022;32:452–61. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.sart.2022.01.003.

McLendon PB, Christmas KN, Simon P, et al. (2021) Machine learning can predict level of improvement in shoulder arthroplasty. JB JS Open Access 6: https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.OA.20.00128.

Polce EM, Kunze KN, Fu MC, et al. Development of supervised machine learning algorithms for prediction of satisfaction at 2 years following total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2021;30:e290–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2020.09.007.

Calkins TE, Mosher ZA, Throckmorton TW, Brolin TJ. Safety and cost effectiveness of outpatient total shoulder arthroplasty: a systematic review. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2022;30:e233–41. https://doi.org/10.5435/JAAOS-D-21-00562.

Benson RT, Drew JC, Galland RB. A waiting list to go home: an analysis of delayed discharges from surgical beds. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2006;88:650–2. https://doi.org/10.1308/003588406X149246.

Costa AP, Poss JW, Peirce T, Hirdes JP. Acute care inpatients with long-term delayed-discharge: evidence from a Canadian health region. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:172. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-172.

Rosman M, Rachminov O, Segal O, Segal G. Prolonged patients’ In-Hospital Waiting Period after discharge eligibility is associated with increased risk of infection, morbidity and mortality: a retrospective cohort analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:246. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-0929-6.

Groot OQ, Bindels BJJ, Ogink PT, et al. Availability and reporting quality of external validations of machine-learning prediction models with orthopedic surgical outcomes: a systematic review. Acta Orthop. 2021;92:385–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2021.1910448.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Data sharing

All data pertaining to this research article are included within the manuscript as written.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.H.K. and J.L. were involved in the design and conception of this manuscript. A.H.K. and J.L. performed the literature search, gathered all data, compiled the primary manuscript, and compiled the figures. M.A.S, J.A.A., A.M., and O.R. critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and gave final approval of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The approval and consent were waived by the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, USA, and Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, OH, USA.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Karimi, A.H., Langberg, J., Malige, A. et al. Accuracy of machine learning to predict the outcomes of shoulder arthroplasty: a systematic review. Arthroplasty 6, 26 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42836-024-00244-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42836-024-00244-4