Abstract

This work investigates the splashing behaviors of droplets impacting on solid surfaces and mainly focuses on the characteristics of secondary droplets. According to the experimental results, two different splashing patterns, corona splash and levitating-lamella breakup, are observed. A new breakup mode, named rim-segmenting, is found during the levitating-lamella breakup. In particular, the detailed information of the splashing secondary droplets, including the size, velocity, angle, and total volume of the splashing secondary droplets is obtained from the experimental data. The size distribution of the splashing secondary droplets obeys the gamma distribution function. The average diameter and splashing angle of the secondary droplets are mainly related to the Reynolds number Re, and can be expressed as functions of Re. High impact velocity and liquid viscosity will result in a wider size distribution range of splashing secondary droplets. We also put forward an empirical model to predict the total splashing volume, which is consistent with the experimental data both in this work and previous studies. This work is believed to provide insights on the prediction of the characteristics of splashing secondary droplets.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Collisions between droplets and solid surfaces usually take place in numerous engineering fields, e.g. inkjet printing, spray cooling, surface coating, pesticide delivery, and aircraft anti-icing [1,2,3,4]. In particular, when supercooled large droplets (SLD) impact on an airfoil surface, the ice accretion phenomenon will occur and therefore affect the aerodynamic performance of aircraft, which is a serious threat to flight safety beyond the anti/de-icing system [5]. In the past few decades, many flight accidents caused by aircraft ice accretion have occurred in the world. The study of impingement and icing of supercooled droplets has been accompanied by the development of the aviation industry for a long time and has attracted more and more attention [6,7,8].

At present, numerous studies about the splashing behaviors of droplets impacting on solid walls have been conducted and focused on the exploration of the droplet–wall interaction for a single water droplet [9,10,11,12,13]. The splashing behaviors of impinging droplets are mainly controlled by the comprehensive effects of solid-liquid-gas phases. The droplet impact velocity (U0) and diameter (D0), liquid density (ρ), viscosity (µ) and surface tension (σ), surface roughness and wettability, and the properties of surrounding gas, ambient temperature are all found to play important roles in droplet splashing [14,15,16,17].

The splashing threshold and characteristics of secondary droplets are closely related to the ice accretion prediction on solid surfaces. Scholars have put forward numerous splashing criteria, expressed by dimensionless parameters, such as Reynolds number (Re = ρD0U0/µ), Weber number (We = ρD0U02/σ), Ohnesorge number (Oh = We1/2/Re), and Capillary number (Ca = We/Re), to forecast the occurrence of droplet splashing. We summarized the splashing criteria proposed by different scholars in recent years [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24], as shown in Table 1. However, these splashing criteria are all based on some assumptions or special conditions, and no certain splashing criterion can accurately predict the droplet splashing under all conditions.

After splashing occurs, it is important to obtain the characteristics of secondary droplets, including the splashing size, velocity, angle, and total splashing volume, to determine the wall water collection efficiency and the motion behavior of the re-injection droplet [25, 26]. Because of the extremely high splashing velocity and small size of secondary droplets, it is difficult to accurately measure the characteristics of splashing droplets. Using the traces left on paper, Xu measured the size distribution of secondary droplets whose diameters are larger than 100 µm [16]. The experiments of Thoroddsen et al. revealed a size range from 5 to 60 μm for droplet splash on smooth surfaces by use of high-speed cameras with sufficient spatial and temporal resolution [27]. Faßmann et al. made use of shadowgraph techniques and captured droplets larger than 30 μm, providing more accurate size and velocity distributions than previously available [28]. Riboux and Gordillo extended their theory and put forward a prediction model to calculate mean sizes and velocities of the ejected drops [17, 29]. Subsequently, Burzynski et al. studied the size distribution, splashing velocity, splashing angle, splashing volume of secondary droplets [24]. They found that in high-speed collisions, the splashing parameters of secondary droplets are mainly controlled by Reynolds number Re and the dimensionless average diameter Dsa/D0 is positively proportional to Re−1/2.

At present, the water droplet impact experiments are mainly carried out at room temperature environment. However, the physical properties of supercooled droplets are distinctly different from droplets at room temperature. Table 2 lists the physical parameters of water at different temperatures. Compared with the room-temperature water, the viscosity of supercooled water greatly increases but the surface tension and density remain almost constant. It was found that the viscosity would promote splash at low Ohnesorge numbers but suppress splash at high Ohnesorge numbers in our previous work [30]. Therefore, the variation of liquid viscosity cannot be ignored when predicting the ice accretion of SLDs.

Here, we conduct the impact experiments to study the splashing behaviors of droplets impacting on solid surfaces and mainly focus on the characteristics of secondary droplets. The present paper is organized as follows: In Section 2, the experimental setup and imaging processing method are briefly introduced. Next, we discuss the splashing threshold, splashing diameter, velocity, angle, the total volume of secondary droplets in detail in Section 3. The conclusions of this work are summarized in Section 4.

2 Experimental method

2.1 Experimental setup

In this work, we employ glycerol solutions with a range of volume ratios, whose viscosity varies from 1mPa·s to 6.27 mPa·s, to replace the supercooled water. Detailed properties of the liquids are listed in Table 3. We conduct the impact experiments on smooth polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) surfaces. The static contact angle, advancing angle, and receding angle are measured as θ = 60○ ± 2○, θa = 75○ ± 1○, and θr = 45○ ± 2○, respectively. The experimental setup used in the present study has been described in great detail in our previous work [30,31,32,33], as shown in Fig. 1, and will be briefly summarized as follows.

We perform two methods to generate droplets with various velocities and diameters. Incisional liquid drops of millimetric size (D0 = 3.7 ± 0.1 mm or 2.7± 0.1 mm) are detached from fine capillary tubes with different diameters attached to a syringe pump and impinge upon a dry smooth surface from varying heights (Fig. 1(a)). The impact velocity U0 ranges from 1.4 m/s to 5 m/s. In order to generate droplets of micrometer size and with high velocities, a high-pressure water tank and nozzles with different sizes are used to atomize microdroplets (Fig. 1(b)). By adjusting the pressure of the tank and the diameter of the nozzle, droplets with micrometer sizes (200-2000 μm), and high velocities (3 m/s-20 m/s) are generated.

The dynamical processes of the drop impact are recorded using two high-speed cameras (NOVAS12 and Mini UX100, Photron, at 20 000 and 8 000 fps, respectively) with two macro lenses (AF Micro-Nikkor, 60 mm 1:2.8 D and 200mm f/4D IF) from side-view and top-view, respectively. The spatial resolution of the obtained snapshots can be up to 20 μm/pixel. All experiments are performed in air, at isothermal and normal atmospheric conditions (~ 20℃, 1 atm), and repeated at least three times for each condition.

2.2 Image processing

The processing of high-resolution image sequences obtained from side view helps us to obtain the details of secondary droplets. Here, the open source software Image J is employed for image processing. The procedure of image processing is briefly illustrated in Fig. 2 (a)-(d), including image binarization, particle identification, particle tracking [35]. As shown in Fig. 2(e), the effect of the depth of field df must be considered when processing the side view image [24].The value of df can be directly calibrated and df ≈ 8 mm. At the position that is ld away from the collision position of the droplet, we select a control surface (as shown in Fig. 2(e) and (f)), and count the size Dspi and velocity Uspi of each secondary droplet that crosses the control surface. Here, the statistical period is from the beginning to the end of the splashing process, and the secondary droplets are tracked from the pinch-off moment, as shown in Fig. 2(d). Once the droplets are detached from the lamella rim, the velocities of each secondary droplets are almost constant in the measurement field and can be accurately obtained. The position of control surface, i.e. ld, is an important parameter during the processing procedure. If ld is too small, amounts of droplets are overlapped when crossing the control surface. The visual field of the high-speed camera used in this work is 1024 × 512 pixels, and the maximum size of drops is about 185 pixels. Therefore, the position of capture surface is selected as ld ≈ 2.5D0 in this work to satisfy the statistics need. Because of the quasi-axisymmetric distribution of splashing secondary droplets on smooth surfaces, the information of secondary droplets in the depth of field can represent the distribution characteristics of all secondary droplets. In particular, the total splashing volume can be obtained according to the geometric relationship of the circle, and the total splashing volume ε can be expressed as:

3 Results and discussions

3.1 Splashing criterion

Plenty of splash thresholds have been proposed to predict the occurrence of drop splash, such as OhRe1.25 (Mundo et al., 1995) [19], Ca (Vander Wal et al., 2006) [20], OhgOh5/3Re5/3 (low-Oh) and OhgOhRe1.25 (high-Oh) (Riboux and Gordillo, 2014) [17], which indicates the divergence about the effect of liquid viscosity on splashing.

In the prior work [30], we have investigated the influence of liquid viscosity on droplet splashing in detail, and found the liquid viscosity plays a reversed role on the droplet splashing, i.e. the liquid viscosity promotes the droplet splashing in the low-viscosity cases but suppresses the droplet splashing in the high-viscosity cases. We eventually put forward a splash criterion on smooth surfaces, which could successfully characterize the splashing behavior in this work and previous studies, and indicate the reversed role of liquid viscosity on drop splash [30]:

3.2 Formation of secondary droplets

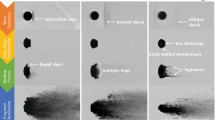

When droplets impinge on a smooth surface with relatively high velocities, two different splashing patterns can be distinguished: Corona splashing for low-viscosity droplets (Fig. 3(a)); Levitating lamella breakup for high-viscosity droplets (Fig. 3(b)). There is a significant divergence on the formation of secondary droplets during the splashing process, as shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3(a) shows the formation of secondary droplets of corona splash, which is similar to the Savart sheet breakup of a droplet impacting on a small target [36,37,38]. The lifting lamella is encompassed by a rim on which the ligaments grow to finally eject secondary droplets. Droplets breakup occurs continuously during lamella expansion in the form of four modes of droplet ejection. The first mode is end-pinching: A droplet is ejected at the end of the ligament under the capillary deceleration of the tip. Ligament-merging followed by end-pinching is another ejection mode: Due to the non-uniform distribution of mass per unit arc-length the ligament will be merged and secondary droplets are ejected at the end of the merged ligament. The third mode is filament-rupturing: As the ligaments merging and rims retracting, filaments will be formed at the cusps position and finally rupture into secondary droplets. The last mode is satellite droplets: One or multiple small satellite droplets may be formed during the end-pinching and filament-rupture process.

However, the breakup modes of levitating-lamella are completely distinct from the corona splashing, as shown in Fig. 3(b). The increase of viscosity may result in a delayed ejection time of the lamella and a low lifting angle [30]. The lamella cannot be lifted as a corona, and a thinner sheet of liquid is ejected and travels outward nearly parallel to the substrate, named levitating-lamella, which has been reported in prior works [39, 40]. We could divide the formation of secondary droplets of levitating-lamella breakup into three modes: inner filament-rupturing, rim-segmenting, and satellite droplets. Here, the main feature of the breakup of levitating-lamella is that the inner breakup of lamella prefers to occur than the edge-rim breakup. Because of the high-viscosity (compare Fig. 3(a) and 3(b)), no ligaments are formed on the circular rim, and the levitating lamella is firstly broken, with the formation and rupturing of the inner filaments. Interestingly, after breaking away from the levitating lamella, the unbroken rim will gradually expand and be segmented into multiple secondary droplets, named rim-segmenting. The satellite droplets are also formed during the levitating-lamella breakup process.

3.3 Size distribution of secondary droplets

We define the dimensionless diameter of the secondary droplets as Dsp/D0 and present the probability distribution of Dsp/D0 under different collision conditions in Fig. 4. The gamma distribution function is employed to represent the size distribution characteristic of secondary droplets. The gamma distribution function is expressed as [36]:

where, x is the random variable, i.e., Dsp/D0 in this work. α and β represent the shape parameter and the scale parameter of the gamma distribution function, respectively. The shape parameter implies the degree of the concentration of the data, and the scale parameter corresponds to the mean value of the data set.

Figure 4(a)-(d) represent the probability distribution of dimensionless diameter Dsp/D0 under different viscosity and same impact velocity (U0 = 5 m/s). For low-viscosity droplets, the size distribution of splashing secondary droplets concentrates on a narrow range (Dsp/D0 < 0.02). With the increase of the droplet viscosity, the size distribution of splashing secondary droplets is gradually extensive, corresponding to the larger variance. Figure 4(b), (e), and (f) represent the probability distribution of dimensionless diameter Dsp/D0 under different impact velocities. High impact velocity would result in the wider size distribution range of splashing secondary droplets.

Probability distribution of dimensionless diameter Dsp/D0 of splashing secondary droplets under different impact conditions: a 20 % glycerol solution, D0 = 3.7 mm, U0 = 5 m/s, We = 1478, Re = 9085; b 30 % glycerol solution, D0 = 3.7 mm, U0 = 5 m/s, We = 1536, Re = 6890; c 40 % glycerol solution, D0 = 3.7 mm, U0 = 5 m/s, We = 1647, Re = 4870; d 50 % glycerol solution, D0 = 3.7 mm, U0 = 5 m/s, We = 1771, Re = 3152; e 30 % glycerol solution, D0 = 3.7 mm, U0 = 4.1 m/s, We = 1064, Re = 5733; f 30 % glycerol solution, D0 = 3.7 mm, U0 = 3.4 m/s, We = 709, Re = 4681. The red curve in each figure indicates the Gamma distribution fitting curve

Many previous studies have confirmed that the size of secondary droplets is related to the lamella and rim thickness, which is proportional to the liquid viscosity. Roisman et al. [41,42,43] found that the average diameter of the secondary droplets for the spray impacts scales to the thickness hµ of the viscous boundary layer, dsa = Dsa/D0 ~ Re−1/2. Burzynski et al. [24, 26] also proved this semi-empirical model is suitable to the splashing of high-speed droplets impacting a dry surface. Figure 5 shows the relationship between the dimensionless average diameter dsa of secondary droplets and Reynolds number Re under different experimental conditions.

The symbol color in Fig. 4 represents the range of Weber number We. The average diameter of the splashing secondary droplets is mainly related to the Reynolds number Re for a wide range of Weber number We, 300 < We < 8300. We found the secondary droplets diameters of corona splash and levitating-lamella breakup all follow the semi-empirical model dsa = Dsa/D0 ~ Re−1/2. By fitting the experimental data, the dimensionless average diameter dsa = Dsa/D0 is expressed as a function of Reynolds number Re:

where, the R-squared value, which represents the goodness of fit, of Eq. 4 is 0.58.

3.4 Splashing velocity and angle

The dimensionless splashing velocity of secondary droplets is defined as U* = Usp/U0, and the variation tendency of U* over time (t = TU0/D0) is shown in Fig. 6(a) under all experimental conditions. Here, the velocities of secondary droplets in this study are measured using the Image J software. The secondary droplets are tracked from the pinch-off moment, and the measured instantaneous velocity should be equal to the velocity of the lamella rim, from where the secondary droplets are ejected. Once the droplets are detached from the lamella rim, the velocities are almost constant in the measurement field. Numerous studies also have shown that the splashing velocity of the secondary droplets is same as the velocity of the liquid lamella edge where the secondary droplets are ejected, and U* ~ t−1/2 [24, 29]. By fitting the experimental data in Fig. 6(a), the normalized curve between the dimensionless splashing velocity U* and the dimensionless time t can be obtained:

where, the R-squared value of Eq. 5 is 0.85.

Figure 6(b) shows the relationship between the distribution range of splashing angle and Reynolds number Re under different experimental conditions. The upper and lower limits of the error bands represent the maximum splashing angle (φsp)max and the minimum splashing angle (φsp)min, respectively. Similarly, we could obtain the expressions of (φsp)max and (φsp)min:

where, the R-squared values of (φsp)max and (φsp)min are 0.84 and 0.74, respectively. Equation 6 could predict the splashing range of secondary droplets, as the shadow area shows in Fig. 6(b).

3.5 Total splashing volume

Through the statistical method introduced above (Eq. 1), the total splashing volume can be evaluated under different experimental conditions. Burzynski et al. obtained a semi-empirical model of the total splashing volume, expressed as a quadratic function of the splashing threshold [24, 26]. Inspired by their work, we also employ power law function to represent the correlation between total splashing volume and the proposed splashing threshold (Eq. 2) in low-Oh cases. As shown in Fig. 7, the black and red lines represent the fitting curves using the correlation of ε ~ (K − K0)2 and (K − K0)3, respectively. The R-squared values are 0.74 for (K − K0)2 and 0.81 for (K − K0)3. Therefore, we can obtain a new model to predict the total splashing volume ε using the correlation of (K − K0)3:

where K = ReOh1.3 and K0 ≈ 3.8. The proposed splashing volume model is consistent with the experimental data both in the present work and the reference, which verified the universality of the prediction formula (Eq. 7).

Relation between the total splashing volume ε and the splashing threshold K. Different symbols represent the experimental data using different kinds of liquid. The black dotted line shows the fitting curve using ε ~ (K − K0)2 (R-squared value = 0.74), and the red solid line shows the fitting curve using ε ~ (K − K0)3 (R-squared value = 0.81), which is more reasonable for the correlation

4 Conclusions

To conclude, the present work studies the splashing behaviors of droplets impacting on solid surfaces and focuses on the characteristics of splashing secondary droplets. Two different splashing patterns can be distinguished: corona splashing for low-viscosity droplets, and levitating-lamella breakup for high-viscosity droplets. Four modes of the formation of secondary droplets during corona splash are defined: end-pinching, ligament-merging followed by end-pinching, filament-rupturing, and satellite droplets. We found a new breakup mode, named rim-segmenting, during the levitating-lamella breakup process. Through processing the images from high-speed photography, detailed information of the splashing secondary droplets is obtained, including the size, velocity, angle, and total volume. Emphatically, several empirical formulas are proposed to predict the characteristics of secondary droplets. The size distribution of the secondary droplets resulting from the splashing obeys the gamma distribution function. The average diameter and splashing angle of the secondary droplets are mainly related to the Reynolds number Re, and can be expressed as functions of Re. We also put forward an empirical model to predict the total splashing volume ε ~ (K − K0)3, which is consistent with the experimental data both in the present work and the reference. This work is believed to provide a better understanding of droplet splashing and valuable insights into numerous engineering fields, e.g. spray cooling, surface coating, and aircraft anti-icing.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Cao Y, Xin M (2019) Numerical simulation of supercooled large droplet icing phenomenon: a review. Arch Comput Method E 27(4):1231–1265

Hao P, Lv C, Zhang X (2014) Freezing of sessile water droplets on surfaces with various roughness and wettability. Appl Phys Lett 104(16):161609

Cebeci T, Kafyeke F (2003) Aircraft icing. Annu Rev Fluid Mech 35(1):11–21

Grabowski WW, Wang LP (2013) Growth of cloud droplets in a turbulent environment. Annu Rev Fluid Mech 45(1):293–324

Wu Z (2018) Drop “impact” on an airfoil surface. Adv Coll Interface Sci 256(1):23–47

Li H, Chen F, Hu H (2015) Simultaneous measurements of droplet size, velocity and temperature of “in-flight” droplets in a spray flow by using a molecular tagging technique. 53rd AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting, AIAA 2015–1224

Zhang K, Zhang S, Rothmayer A, Hu H (2013) Development of a digital image projection technique to measure wind-driven water film flows. 51st AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting including the New Horizons Forum and Aerospace Exposition, AIAA 2013–0247

Zhou W, Johnson B, Hu H (2015) An experimental study of compressibility effects on the film cooling effectiveness using PSP and PIV techniques. 53rd AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting, AIAA 2015–0352

Jin Z, Wang Z, Sui D, Yang Z (2016) The impact and freezing processes of a water droplet on different inclined cold surfaces. Int J Heat Mass Transf 97:211–223

Jin Z, Zhang H, Yang Z (2017) Experimental investigation of the impact and freezing processes of a water droplet on an ice surface. Int J Heat Mass Transf 109:716–724

Jin Z, Zhang H, Yang Z (2017) The impact and freezing processes of a water droplet on different cold cylindrical surfaces. Int J Heat Mass Transf 113:318–323

Yarin AL (2006) Drop impact dynamics: splashing, spreading, receding, bouncing…. Annu Rev Fluid Mech 38(1):159–192

Josserand C, Thoroddsen ST (2016) Drop impact on a solid surface. Annu Rev Fluid Mech 48(1):365–391

Hao J (2017) Effect of surface roughness on droplet splashing. Phys Fluids 29(12):122105

Xu L, Zhang WW, Nagel SR (2005) Drop splashing on a dry smooth surface. Phys Rev Lett 94(18):184505

Xu L (2007) Liquid drop splashing on smooth, rough, and textured surfaces. Phys Rev E 75(5):056316

Riboux G, Gordillo JM (2014) Experiments of drops impacting a smooth solid surface: a model of the critical impact speed for drop splashing. Phys Rev Lett 113(2):024507

Stow CD, Hadfield MG (1981) An experimental investigation of fluid flow resulting from the impact of a water drop with an unyielding dry surface. Proc R Soc Lond A 373:419-441

Mundo C, Sommerfeld M, Tropea C (1995) Droplet-wall collisions: experimental studies of the deformation and breakup process. Int J Multiph Flow 21(2):151–173

Wal RLV, Berger GM, Mozes SD (2005) The splash/non-splash boundary upon a dry surface and thin fluid film. Exp Fluids 40:53–59

Palacios J, Hernández J, Gómez P, Zanzi C, López J (2013) Experimental study of splashing patterns and the splashing/deposition threshold in drop impacts onto dry smooth solid surfaces. Exp Thermal Fluid Sci 44(1):571–582

Stevens CS (2014) Scaling of the splash threshold for low-viscosity fluids. Europhys Lett 106(2):24001

Almohammadi H, Amirfazli A (2019) Droplet impact: viscosity and wettability effects on splashing. J Colloid Interface Sci 553:22–30

Burzynski DA, Roisman IV, Bansmer SE (2020) On the splashing of high-speed drops impacting a dry surface. J Fluid Mech 892(A2):1–30

Burzynski DA, Bansmer SE (2018) Droplet splashing on thin moving films at high Weber numbers. Int J Multiph Flow 101:202–211

Burzynski DA, Bansmer SE (2019) Role of surrounding gas in the outcome of droplet splashing. Phys Rev Fluids 4(7):073601

Thoroddsen ST, Takehara K, Etoh TG (2012) Micro-splashing by drop impacts. J Fluid Mech 706:560–570

Faßmann BW, Bansmer SE, Möller TJ, Radespiel R, Hartmann M (2013) High velocity impingement of single droplets on a dry smooth surface. Exp Fluids 54(5):1516

Riboux G, Gordillo JM (2015) The diameters and velocities of the droplets ejected after splashing. J Fluid Mech 772:630–648

Zhang H, Zhang X, Yi X, He F, Niu F, Hao P (2021) Reversed role of liquid viscosity on drop splash. Phys Fluids 33(5):052103

Zhang H, Zhang X, Yi X, He F, Niu F, Hao P (2021) Effect of wettability on droplet impact: spreading and splashing. Exp Therm Fluid Sci 124:110369

Zhang H, Zhang X, Yi X, He F, Niu F, Hao P (2020) Asymmetric splash and breakup of drops impacting on cylindrical superhydrophobic surfaces. Phys Fluids 32(12):122108

Zhang H, Yi X, Du Y, Zhang R, Zhang X, He F, Niu F, Hao P (2019) Dynamic behavior of water drops impacting on cylindrical superhydrophobic surfaces. Phys Fluids 31(3):032104

Qin M, Tang C, Tong S, Zhang P, Huang Z (2019) On the role of liquid viscosity in affecting droplet spreading on a smooth solid surface. Int J Multiph Flow 117:53–63

Tinevez JY, Perry N, Schindelin J, Hoopes GM, Reynolds GD, Laplantine E, Bednarek SY, Shorte SL, Eliceiri KW (2017) TrackMate: an open and extensible platform for single-particle tracking. Methods 115:80–90

Wang Y, Bourouiba L (2018) Unsteady sheet fragmentation: droplet sizes and speeds. J Fluid Mech 848:946–967

Wang Y, Bourouiba L (2021) Growth and breakup of ligaments in unsteady fragmentation. J Fluid Mech 910:A39

Wang Y, Dandekar R, Bustos N, Poulain S, Bourouiba L (2018) Universal rim thickness in unsteady sheet fragmentation. Phys Rev Lett 120(20):204503

Stevens CS, Latka A, Nagel SR (2014) Comparison of splashing in high- and low-viscosity liquids. Phys Rev E 89(6):063006

Driscoll MM, Stevens CS, Nagel SR (2010) Thin film formation during splashing of viscous liquids. Phys Rev E 82(3):036302

Roisman IV, Tropea C (2005) Fluctuating flow in a liquid layer and secondary spray created by an impacting spray. Int J Multiph Flow 31(2):179–200

Roisman IV, Horvat K, Tropea C (2006) Spray impact: Rim transverse instability initiating fingering and splash, and description of a secondary spray. Phys Fluids 18(10):102104

Roisman IV, Berberović E, Tropea C (2009) Inertia dominated drop collisions. I. On the universal flow in the lamella. Phys Fluids 21(5):052103

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the National Numerical Wind Tunnel Project (Grant No. NNW2019ZT2-B26 and NNW2019ZT2-B05), the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant Nos. 2016YFC1100300 and 2017YFC0111100), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos.11635005, 11632009, 11972215 and 12072174). The authors are grateful to the reviewers and editors for the help of this work.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Numerical Wind Tunnel Project (Grant No. NNW2019ZT2-B26 and NNW2019ZT2-B05), the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant Nos. 2016YFC1100300 and 2017YFC0111100), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos.11635005, 11632009, 11972215 and 12072174).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The contribution of the authors to the work is equivalent. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, H., Gao, Y., Zhang, X. et al. Characteristics of secondary droplets produced by the impact of drops onto a smooth surface. Adv. Aerodyn. 3, 35 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42774-021-00091-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42774-021-00091-w