Abstract

Lysobacter enzymogenes OH11 is a non-flagellated, ubiquitous soil bacterium with broad-spectrum antifungal activities. Although lacking flagella, it employs another type of motile behavior, known as twitching motility that is powered by type IV pilus (T4P) to move towards neighboring crop fungal pathogens to kill them as food. At present, little is known about how this non-flagellated bacterium controls twitching motility that is crucial for its predatory lifestyle. Herein, we present a report on how a non-canonical PilZ domain, PilZLe3639, controls such motility in the non-flagellated L. enzymogenes; it failed to bind with c-di-GMP but seemed to be required for twitching motility. Using bacterial two-hybrid and pull-down approaches, we identified PilBLe0708, one of the PilZLe3639-binding proteins that are essential for the bacterial twitching motility, could serve as an ATPase to supply energy for T4P extension. Through site-mutagenesis approaches, we identified one essential residue of PilZLe3639 that is required for its binding affinity with PilBLe0708 and its regulatory function. Besides, two critical residues within the ATPase catalytic domains of PilBLe0708 were detected to be essential for regulating twitching behavior but not involved in binding with PilZLe3639. Overall, we illustrated that the PilZ-PilB complex formation is indispensable for twitching motility in a non-flagellated bacterium.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The Gram-negative genus of Lysobacter comprises more than 30 species that are emerging as important sources of crop biocontrol agents. They are novel because they exhibit proficient abilities to generate a wide variety of anti-infectious metabolites and extracellular lytic enzymes (Christensen and Cook 1978; Kobayashi et al. 2005; Xie et al. 2012; Panthee et al. 2016). Recent comparative genomic studies uncovered that most members of Lysobacter do not carry a FliC homolog, which encodes flagellin required for the biogenesis of surface-attached flagella (de Bruijn et al. 2015). Therefore, with minor exceptions, most Lysobacter species are, although ubiquitous in the environment, non-flagellated (Christensen and Cook 1978; Hayward et al. 2010).

How do the Lysobacter species without flagella migrate towards a more favorable environment or escape from undesirable conditions in their natural niches? Our earlier studies revealed that surfaced-attached type IV pilus (T4P) can power Lysobacter species to move in a twitching mode (Zhou et al. 2015). This motile behavior seems to facilitate the non-flagellated Lysobacter species to draw near ecologically-relevant pathogens. When Lysobacter species establish the contact with pathogens, they predate or kill them, hence protect the plants from being infected (Xia et al. 2018).

L. enzymogenes is a plant-associated, soil proteobacterium that acts as a predator of crop fungal pathogens (Qian et al. 2009). To prey on nearby fungi, L. enzymogenes is required to move towards them via T4P-dependent twitching motility and further kills these microorganisms through secreting an antibiotic, known as heat-stable antifungal factor, HSAF (Yu et al. 2007; Xia et al. 2018). In our earlier studies, we demonstrated 19 pilus structural or regulatory component proteins, including the major pilus subunit, PilA and the motor proteins PilB and PilT, are required for the biogenesis of T4P and the function of twitching motility in L. enzymogenes OH11 (Xia et al. 2018).

Genes encoding proteins with PilZ domains are widely distributed in a variety of bacterial genomes and control numerous cellular processes, such as biofilm formation, T4P biogenesis, twitching motility, two-component signal transduction, and virulence (Galperin and Chou 2020). These domains could be stand-alone, in tandem, or fused with other signaling domains, such as EAL, GGDEF, or HD-GYP that are highly associated with the signaling of c-di-GMP, a ubiquitous bacterial second messenger Römling et al. 2013, 2005). The first defined PilZ domain is PilZPA2960 that was found in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a human pathogen and model flagellated bacterium (Alm et al. 1996). The PilZPA2960 protein has only one domain, PilZ (Alm et al. 1996; Guzzo et al. 2009), which controls T4P formation and twitching behavior. PilZPA2960 regulates the secretion of PilA polymers to the cell surface (Alm et al. 1996). At the mechanistic level, while PilZPA2960 appears to regulate the T4P formation via protein-protein interactions, the PilZPA2960-binding partners are yet to be characterized (Galperin and Chou 2020). PilZXac1133 from the flagellated, pathogenic Xanthomonas citri is homologous to the PilZPA2960 protein. Crystal structural analyses revealed that PilZXac1133, like PilZPA2960, lacks two conserved signature motifs, RxxxR and [D/N] xSxxG, that are required for c-di-GMP binding (Guzzo et al. 2009; Li et al. 2009, 2011). PilZXac1133 not only binds with PilBXac3239 but also with the degenerated EAL domain of FimXXac398. FimXPA4959 protein of P. aeruginosa, a homolog of FimXXac398, has also been found to be an essential regulator of T4P formation and twitching motility (Huang et al. 2003; Guzzo et al. 2009). The discovery of these various protein-protein interactions implies that PilZXac1133 is involved in regulating T4P formation; however, no corresponding phenotypic evidence is available. Moreover, PilZXac1133, unlike PilZPA2960, did not seem to control twitching motility as described previously (Guzzo et al. 2009). In agreement, X. campestris PliZXc1028, which is almost identical to PilZXac1133, was found to play only a minor role in the twitching behavior (McCarthy et al. 2008). A similar situation has also been observed in the non-flagellated Neisseria meningitides (Carbonnelle et al. 2005). Therefore, PilZPA2960 and its homologs appear to play diversified roles in modulating the formation of T4P and/or twitching motility in different bacterial species with and without flagella.

A search of the genome of strain OH11 led us to discover Le3639, a homologous PilZPA2960 protein that is referred to as PilZLe3639 herein. PilZLe3639 shares a very high (76–83%) sequence similarity with PilZPA2960 and contains no conserved c-di-GMP-binding signature motifs, as described above (Fig. 1a). The objective of this work is to determine whether PilZLe3639 can affect the twitching motility of the non-flagellated L. enzymogenes, and if yes, what is the underlying mechanism? Herein, we showed that PilZLe3639 is indeed involved in controlling the twitching motility of L. enzymogenes. We further found that PilZLe3639 directly interacted with PilBLe0708, which is essential for twitching motility in L. enzymogenes. Moreover, PilZLe3639 seems to use the same residue critical for its role in twitching motility and interaction with PilBLe0708. We underscore for the first time the involvement of the PilZ-PilB protein complex in twitching motility in non-flagellated bacteria, which provides further insights on the functional and mechanistic diversity of PilZ domains in bacteria.

PilZLe3639 is a stand-alone PilZ domain and unable to bind c-di-GMP. a Multiple sequence alignment of the PilZLe3639-like proteins. PilZLe3639, PilZPA2960, Lca55_3236, Lgu3211_1674, Lde18482_475, Lar79_2362, Lco07_960, PilZXac1133 and PilZXc1028 indicated these stand-alone PilZ domains from Lysobacter enzymogenes OH11, Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01, L. capsisi 55, L. gumosus 3.2.11, L. defluvii DSM18482, L. arseniciresistens ZS79, L. concretionis Ko07, Xanthomonas citri and X. campestris, respectively. YcgR (PDB entry 5Y6G), is a c-di-GMP-binding protein from E. coli. The RxxxR and [D/N] xSxxG that are required for c-di-GMP binding (Guzzo et al. 2009) are highlighted by red boxes. Two conserved residues (Y24 and W71) in the selected stand-alone PilZ domains are indicated by purple and green triangles, respectively. b Microscale thermophoresis (MST) assay showed PilZLe3639 failed to bind with c-di-GMP, while c Clp, a known c-di-GMP-binding protein (Xu et al. 2018), showed moderate binding affinities with c-di-GMP determined by MST

Results

PilZLe3639 is a stand-alone PilZ domain unable to bind c-di-GMP

A genomic search of strain OH11 by using PilZPA2960 as the bait enabled us to identify PilZLe3639, a homologous protein in L. enzymogenes with a stand-alone PilZ domain (Fig. 1a) that shared 76%, 82%, and 83% sequence similarity with PilZPA2960, PilZXac1133, and PilZXc1028, respectively. The homologous PilZLe3639 proteins were also present in several selected Lysobacter species (Fig. 1a). Multiple sequence alignment revealed that PilZLe3639 and its homologs from other selected Lysobacter species all lacked the conserved c-di-GMP-binding motifs described above (Fig. 1a). To experimentally validate this finding, we purified the PilZLe3639-His fusion protein and subjected it to the microscale thermophoresis (MST) assay. We found no binding signals between the c-di-GMP and PilZLe3639-His (Fig. 1b) could be observed, while c-di-GMP bound well to the control protein Clp (with a Kd of 0.21 μM), a known c-di-GMP-binding transcription factor according to our earlier work (Fig. 1c; Xu et al. 2018). These results suggest that the non-flagellated Lysobacter species carry a conserved stand-alone PilZ domain that does not appear to interact with c-di-GMP as evidenced by PilZLe3639.

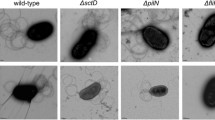

PilZLe3639 is essential for modulating the twitching motility of Lysobacter

To investigate whether PilZLe3639 exhibits a role in affecting the Lysobacter twitching motility, we generated ΔPilZLe3639, an in-frame Lysobacter deletion mutant (Additional file 1: Table S1) via a double homologous-recombination approach as described earlier (Qian et al. 2012). In the twitching-motility inducing medium (1/10 TSA), we found that the wild-type OH11 displayed an apparent twitching behavior by spreading single or clustered cells outside from the colony margin (Fig. 2). At the same time, the inactivation of PilZLe3639 completely abolished this twitching phenomenon (Fig. 2). The twitching motility defect in the PilZLe3639 mutant was fully rescued by complementation with a plasmid-borne PilZLe3639 (Fig. 2) but not by an empty plasmid (Fig. 2). These results imply the crucial role of PilZLe3639 in triggering the Lysobacter twitching motility. According to an earlier study (Guzzo et al. 2009), Tyr24 (Y24) and Trp71 (W71) are the two potential key residues for executing the biological function of PilZXac1133. To figure out whether they also play a similar role in PilZLe3639, we generated two individual mutants of Y24A (A is an abbreviation of Alanine) and W71A, respectively, and complemented these PilZLe3639 variants with the plasmid harboring Y24A or W71A substitution. The results (Fig. 2) showed that the Y24 mutant behaves like the wild-type allele and can rescue the twitching motility defect of the pilZLe3639 mutant. However, the W71 mutant allele did not restore the normal twitching motility phenotype, indicating W71 is a key residue for protein activity. These results collectively suggest that PilZLe3639 is required for twitching motility, and the amino residue of W71 is essential for displaying such a function.

PilZLe3639 and its residue W71 both played essential roles in the formation of twitching motility by L. enzymogenes. Mutation of pilZLe3639 in wild-type OH11 led to a complete defect in forming twitching motility, as no twitching cells (indicated by blight arrows) were observed at the margin of strain colony. Complementing the wild-type PilZLe3639 or a variant carrying a Y24-A24 substitution (indicated as Y24A) into the mutant both rescued this motile deficiency. Introducing the empty vector (pBBR1-MCS5, abbreviated as pBBR) or the pilZLe3639 variant possessing a W71-A71 replacement (indicated as W71A) failed to rescue the twitching deficiency of the pilZLe3639 mutant

Binding of PilZLe3639 with PilBLe0708 is required for twitching motility

To understand how PilZLe3639 modulates the Lysobacter twitching motility, we screened a total of 19 pilus-associated structural or regulatory proteins (Xia et al. 2018) to identify the direct PilZLe3639-binding partner(s) (Fig. 3a). For screening, we employed the bacterial adenylate cyclase two-hybrid (BACTH) system (Ouellette et al. 2017). Each of the 19 genes was individually cloned into the pKT25 vector to generate the prey pKT25 constructs. Along with the bait plasmid pUT18c-PilZLe3639, each of the recombinant prey pKT25 constructs was co-transformed into the E. coli BTH101, which was further grown in a selective medium. Based on the principle of the BACTH system, if bait PilZLe3639 established a direct interaction with the prey protein, the co-transformed E. coli strain would exhibit a “blue” phenotype. Via this approach, we found that among the 19 proteins, only PilBLe0708 interacted directly with PilZLe3639 (Fig. 3b). To validate this observation, we further tested the ability of PilZLe3639-His to pull down GST-PilBLe0708, which was indeed the case since we observed a positive signal (Fig. 3c). These results reveal that PilZLe3639 directly interacted with PilBLe0708 of L. enzymogenes.

PilZLe3639 directly interacted with PilBLe0708, a characterized pilus motor protein.a, b pKT25-PilZLe3639 with the recombinant pUT18c carrying different pilus-associated proteins that are required for twitching motility in L. enzymogenes OH11 (Xia et al. 2018) were co-transformed into the E. coli BTH101 cells to test their potential protein-protein interactions by the bacterial adenylate cyclase two-hybrid (BACTH) system. The co-transformed E. coli colony with a “blue” color indicated the test protein-protein interactions happened under the test conditions. Using this approach, only PilBLe0708 with PilZLe3639 showed an interaction signal. “+”, a positive control (pUT18c-Zip &pKT25-Zip), “-”, a negative control (pUT18c &pKT25). c GST pull-down assay confirmed the direct binding of PilZLe3639 with PilBLe0708 in vitro

Multiple sequence alignment showed that PilBLe0708 possessed two conserved motifs, the Walker A and Walker B (boxed in red rectangular in Fig. 4a), both of which are highly required for its enzymatic activity (Chiang et al. 2008). Between the predicted Walker A and B motifs, the residues of Lys333 (K333) and Glu397 (E397) of PilBXac3239 were previously shown to play potential key roles in forming the PilBXac3239-PilZXac1133 complex (Guzzo et al. 2009). Therefore, we constructed the PilBLe0708 variants with a K333A or E397A substitution in the wild-type chromosome and subsequently tested the ability of the mutant strains in producing the L. enzymogenes twitching motility. We found that the chromosomal replacement of Lys333 or Glu397 in the wild-type OH11 completely abolished the bacterial twitching motility (Fig. 4b), suggesting that both residues are essential for the function of PilBLe0708, which supports the earlier notion that the enzymatic activity and functionality of PilB are highly associated. To validate that the above observations are site specific, two unrelated residues, Pro208 or Tyr209 of PilBLe0708, were further selected for replacement by Alanine (A) (Fig. 4a). We found that the P208A or Y209A substitution did not seem to affect the L. enzymogenes twitching motility (Fig. 4b). Therefore, the PilZLe3639-PilBLe0708 binding pair appears to correlate well with their functional outcomes in regulating the formation of twitching motility in L. enzymogenes.

The K333 and E397 residues were required for the regulation of PilBLe0708 in the formation of twitching motility in L. enzymogenes OH11. a Multiple sequence alignment of the PilBLe0708-like proteins. PilB proteins acted as ATPase to supply energy via ATP hydrolysis to promote the extension of type IV pilus (T4P). PilBLe0708, PilBPA4526, PilBXac3239, Lca55_4006, Lgu3211_3877, Lde18482_558, Lar79_1239, Lco07_419, indicated these PilB proteins from Lysobacter enzymogenes OH11, Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01, Xanthomonas citri, L. capsisi 55, L. gumosus 3.2.11, L. defluvii DSM18482, L. arseniciresistens ZS79, and L. concretionis Ko07, respectively. PilTLe3094 served as the PilT protein from L. enzymogenes OH11, which functioned as ATPase to supply energy via ATP hydrolysis to elicit the retraction of T4P. “Walker A” and “Walker B” are two known motifs that are essential for the ATPase activity of the PilB or PilT family proteins. The conserved P208, Y209, K333 and E397 residues are indicated by green, orange, red and blue triangles, respectively. b Involvement of the K333 and E397 residues in the regulation of PilBLe0708 in twitching formation. Mutation of PilBLe0708 in wild-type OH11 fully impaired twitching motility, while complementation of the plasmid-borne pilBLe0708 rescued this defect. At the wild-type background of strain OH11, chromosomal replacement of K333 to A333 (K333A) or E397 to A397 (E397A), but not P208-A208 (P208A) and Y209-A209 (Y209A) abolished the strain in producing twitching cells

W71 of PilZLe3639 is required for PilZLe3639-PilBLe0708 interaction

To provide molecular details for the PilZLe3639-PilBLe0708 binding, we tried to identify key residue(s) of PilZLe3639 or PilBLe0708 that are important for their binding and function. For this purpose, we first selected the residues of W71 and Y24 of PilZLe3639 as a comparable pair, because we already showed that the former was necessary for the involvement of PilZLe3639 in twitching motility, while the latter was not (Fig. 2). Using the BACTH system, we found that the PilZLe3639 W71A variant exhibited almost entirely impaired binding capability, while the PilZLe3639 Y24A variant did not seem to demonstrate any binding with PilBLe0708 (Fig. 5a). These results collectively indicate that W71 is a key residue of PilZLe3639 in determining its binding affinity with PilBLe0708 and to regulate the in vivo twitching motility.

Identification of key amino residues of PilZLe3639 or PilBLe0708 that required for their binding determined by the BACTH system. a The W71, but not the Y24 residue of PilZLe3639 was essential for its binding with PilBLe0708. The Y24 and W71 residues were site-mutated respectively, and cloned into pKT25 vector. The coding region of PilBLe0708 was cloned into pUT18c. b All the test residues of PilBLe0708, including P208, Y209A, K333, E397 were not involved in the binding PilBLe0708 with PilZLe3639. “+”, a positive control (pUT18c-Zip &pKT25-Zip), “-”, a negative control (pUT18c &pKT25). c A schematic model for the PilZLe3639-PilBLe0708 complex regulating T4P-dependent twitching motility in Lysobacter enzymogenes OH11. PilBLe0708 is an ATPase responsible for pilus extension. PilZLe3639 may activate (indicated by a dashed arrow) pilus extension through interacting with PilBLe0708. The red cycle indicated the W71 reside of PilZLe3639 which is the key amino acid critical for its role in twitching motility and interaction with PilBLe0708. PilCLe0709 is an integral membrane protein functioning as the platform protein of pilus, while PilQLe2803 acts as the outer membrane secretin pore (Xia et al. 2018)

To map the residues of PilBLe0708 that are essential for influencing its direct interaction with PilZLe3639, we tested the binding of the PilZLe3639 with several PilBLe0708 variants (PilBLe0708K333A, PilBLe0708E337A, PilBLe0708P208A, and PilBLe0708Y209A) through the BACTH system and found that, like the native PilBLe0708, all the tested PilBLe0708 variants seemed to be able to bind well with PilZLe3639 under the testing conditions (Fig. 5b). These results suggest that while K333 and E397 of PilBLe0708 are required for its own regulation in twitching motility, both of them are not likely involved in the PilBLe0708-PilZLe3639 binding.

Discussion

Twitching motility is arguably one of the best-characterized motile behaviors in bacteria (Burrows 2012). Unlike the flagellum-driven swimming or swarming motility, the formation of twitching motility is powered instead by the type IV pilus (T4P) (Chang et al. 2016). Not only for motility, the plant and human pathogenic bacteria also use T4P-mediated twitching motility to promote bacterial infections (Burrows 2012; Dunger et al. 2016; Corral et al. 2020). In the past decade, the transcription, post-transcription, and post-translation regulations of twitching motility have been well-documented from various bacterial systems (Burrows 2012; Craig et al. 2019). Among the twitching motility regulators, the PilZPA2960 protein is an original, stand-alone PilZ domain that exhibits both post-translation and protein-protein interaction capabilities in controlling T4P biogenesis and twitching motility (Alm et al. 1996; Guzzo et al. 2009). Afterwards, several PilZPA2960 homologs, i.e. PilZXac1133 and PilZXc1028, were identified from the flagellated, plant pathogenic Xanthomonas spp. (Guzzo et al. 2009). Interestingly, unlike PilZPA2960, the PilZXac1133 and PilZXc1028 proteins are potentially not involved in the establishment of twitching motility in their respective host systems (McCarthy et al. 2008; Guzzo et al. 2009). These earlier observations indicate the diversified roles of the homologous PilZPA2960 proteins in different bacterial species with flagella. In the previous study, we provided solid evidence to show that PilZLe3639 is indeed a homolog of PilZPA2960, and was able to regulate twitching motility in the non-flagellated soil bacterium of L. enzymogenes (Qian et al. 2009). In this aspect, PilZLe3639 seems to be involved in twitching motility prompting non-flagellated bacterium to move towards fungi to a close range for contact (Patel et al. 2010, 2011). The resulting interaction of L. enzymogenes-fungi favours the non-flagellated bacteria to kill fungal pathogens to acquire nutrients, an aspect regarded as gaining adaptive advantage in natural niches. To our knowledge, this is the first report of the involvement of the widespread stand-alone PilZ domains in controlling twitching motility in non-flagellated bacteria, particularly in the biocontrol agent of phytopathogenic fungi.

In this study, we provide some further insights into how the stand-alone PilZ domains affect twitching motility in non-flagellated bacteria. In our case (Fig. 5c), we found that PilZLe3639 formed a binary complex with PilBLe0708, which is needed to transduce the signaling event for twitching motility. While the PilZXac1133-PilBXac3239 binding has been proved under the in vitro condition in the flagellated Xanthomonas spp. (Guzzo et al. 2009), whether such a protein-protein interaction contributes to twitching motility regulation is, however, not experimentally documented. Moreover, besides PilBXac3239, PilZXac1133 also directly interacts with FimXXac2398, which is a known regulator of T4P (Guzzo et al. 2009). Again, direct experimental evidence supporting the involvement of the PilZXac1133-FimXXac2398 complex in twitching motility is also lacking. Despite the hypothesis that PilZPA2960 most likely forms a complex with a T4P regulator and/or structural-component to co-activate the production of twitching motility in P. aeruginosa, both the PilZPA2960-PilBPA4526 and PilZPA2960-FimXPA4959 bindings, however, were not observed in this bacterium (Qi et al. 2012). Instead, FimXPA4959 was shown to form a complex directly with PilBPA4526 in P. aeruginosa, and this complex is vital for the “correct” polar-localization of both partners, which is essential for their co-involvement in the assembly of T4P (Jain et al. 2017). Therefore, the discovery of the PilZLe3639-PilBLe0708 binding presented in this study represents the first evidence that PilZ-PilB complex formation is indispensable for bacterial twitching motility. Besides, we observed that PilZLe3639 uses a crucial residue of W71 to bind with PilBLe0708 and regulate bacterial twitching behavior, which provides a strong association between the PilZLe3639-PilBLe0708 binding and their co-regulation on twitching motility. What is the potent advantage for L. enzymogenes to form the PilZLe3639-PilBLe0708 complex? Our earlier works showed that L. enzymogenes indeed stimulated its own twitching motility when a nearby fungal pathogen is present but failed to generate twitching behavior under the nutrient-rich conditions (Zhou et al. 2015; Zhao et al. 2017). Based on these considerations, it is possible that upon sensing yet unidentified environmental or cellular stimuli, the non-flagellated L. enzymogenes becomes proficient in twitching motility. This attribute allows the biocontrol agent of crop fungal pathogens to access nutrients. It follows then that L. enzymogenes forms or disassembles the PilZLe3639-PilBLe0708 complex to move via twitching or to stop its motility when it lives in a nutrient-limited environment/presence of nearby fungi or nutrient-rich environment/absence of fungi, respectively. Such capacities could match the benefits and economic costs of L. enzymogenes in natural niches.

It is also noteworthy that the PilZLe3639 seems to interact with PilBLe0708, but not PilTLe3094, a protein sharing 37% sequence similarity with PilBLe0708 (Fig. 3b). At present, it is well recognized that PilB and PilT both function as ATPase, with the former supplying energy via ATP hydrolysis to promote T4P extension, while the latter inducing the retraction of T4P (Chiang et al. 2008). Therefore, the PilZLe3639-PilBLe0708 binding might support T4P extension, resulting in regulation of twitching motility. Besides, it was previously documented that for PilBPA4526 of P. aeruginosa, both its ATPase activity and polar localization in cells (Jain et al. 2017) are essential for its function. Whether PilZLe3639 regulates twitching motility by binding with PilBLe0708 to alter its ATPase activity and/or changing the PilBLe0708 cellular localization remains unknown.

It is also noteworthy that recent studies showed that several transcription regulators or chemical signaling systems controlled the T4P-driven twitching motility in L. enzymogenes through a direct or indirect transcription regulation of genes or gene clusters responsible for pilus biogenesis (Chen et al. 2017, 2018; Feng et al. 2019). Unlike these cases, the present study uncovered a protein complex formed by PilZLe3639 and PilBLe0708 that seems to affect pilus extension and hence play a key role in the formation of twitching motility in L. enzymogenes. These findings collectively suggest that the non-flagellated soil bacterium, L. enzymogenes has similarly designed multiple molecular strategies to modulate the twitching behavior in response to environmental stimuli.

Finally, according to earlier studies, T4P-mediated twitching motility enables L. enzymogenes to fully exhibit antagonistic capability against crop pathogens (Xia et al. 2018). The motile behavior helps L. enzymogenes to predate on fungi to derive nutrients and to colonize on the plant/soil surface and/or fungal mycelium. In this viewpoint, the fundamental insights presented in this study might be helpful to increase the biocontrol efficiency of L. enzymogenes in crop field by promoting twitching motility through engineering a more stable PilZ-PilB complex formation.

Conclusions

While the mechanisms by which flagellated bacteria control the formation of type IV pilus and/or twitching motility have been studied extensively, those in non-flagellated bacteria remain mostly unknown. In the present study, we showed the mechanism by discovering the PilZLe3639-PilBLe0708 complex formation required for twitching motility in the non-flagellated, biocontrol bacterium, L. enzymogenes. The binding between PilZLe3639 and the pilus-extension related motor protein PilBLe0708 seems to be specific, as PilZLe3639 failed to interact with other pilus-retraction associated motor protein, PilTLe3094 that shares 37% sequence similarity with PilBLe0708. These findings led us to propose that the PilZLe3639-PilBLe0708 binding seems to influence the process of T4P extension in a non-flagellated, soil bacterium. Our findings not only expand our current knowledge on the mechanistic actions about how bacteria without flagella control the flagella-independent twitching behavior, but also reveal that the biocontrol L. enzymogenes likely engineers the PilZ-PilB complex to enhance twitching capacity. With such mechanism L. enzymogenes is able to search and predate on nearby fungal pathogens, leading to crop protection.

Methods

Bacterial strains, plasmids and growth conditions

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in the present study are listed in the Additional file 1: Table S1. The Escherichia coli strains that are used for plasmid construction were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium with appropriate antibiotics at 37 °C. L. enzymogenes strains were cultivated in LB medium or 1/10 Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB) at 28 °C. When required, appropriate antibiotics (kanamycin, Km, and gentamicin, Gm) were added into the media.

Genetic methods

A double-crossover homologous recombination approach was used to generate an in-frame deletion mutant of PilZLe3639, as described previously (Qian et al. 2012). The primers used in this assay are listed in the Additional file 1: Table S2. In brief, the corresponding primers were employed to amplify the flanking regions of the target gene and cloned into the suicide vector pEX18Gm (Additional file 1: Table S1). The final construct was transformed into the wild-type OH11 by electroporation. After that, the Lysobacter transformants were selected on LB plates supplemented with Km and Gm. Positive colonies were grown in LB medium for 6 h without antibiotics and subsequently plated on LB agar carrying 10% (w/v) sucrose and Km to select the double-crossover colonies. The final in-frame deletions were verified by PCR using the primers listed in the Additional file 1: Table S2.

Plasmid-based complementation assay was carried out as described previously (Qian et al. 2013). Briefly, different primer pairs listed in the Additional file 1: Table S2 were used to amplify the DNA fragment containing the coding region and the predicted promoter of the target gene by PCR, and the target DNA fragment was subsequently cloned into the broad-host vector pBBR1-MCS5 (Additional file 1: Table S1). The final constructed plasmid was transformed into the mutant by electroporation and verified by PCR.

Chromosomal complementation or residue replacement was generated based on the double-crossover homologous recombination, as described previously (Xu et al. 2018). In brief, different primer pairs (Additional file 1: Table S2) were used to amplify DNA fragments containing the coding region and the flanking regions of each gene with or without point mutations by PCR. The purified PCR products were cloned into the suicide vector pEX18Gm to create a target construct (Additional file 1: Table S1), followed by transformation into the wild-type OH11 or mutants by electroporation. The selection of positive colonies and PCR confirmation were similar to those described above.

Twitching motility assay

We investigated twitching phenotype according to our earlier studies (Zhou et al. 2015; Xia et al. 2018). In brief, the wild-type OH11 and its derivatives were inoculated at the edge of a sterilized coverslip containing 1/20 tryptic soy agar (TSA) with 1.8% agar. Following a 24 h incubation at 28 °C, the margin of the test bacterial colonies on the microscope slide was observed under a light microscope. The twitching motility of L. enzymogenes was designated as motile cells or cell clusters growing away from the original colony (Zhou et al. 2015).

Protein expression and purification

The coding region of PilZLe3639 and PilBLe0708 was amplified by PCR with the primers listed in the Additional file 1: Table S2 and cloned into plasmid pET30a or pMAL-p2x to generate the PilZLe3639-His6 and PilBLe0708-MBP protein fusion, respectively (Additional file 1: Table S1). For protein expression and purification, each resulting vector was transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) (Additional file 1: Table S1). The resulting strains were cultivated in LB medium (with 25 μg/mL Km) overnight at 37 °C. Two mL of the overnight culture was transferred into 200 mL of fresh LB at 37 °C and grown with shaking at 220 rpm, until reaching an OD600 of 0.5. Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG, Sigma, USA) was added to a final concentration, 0.8 mM. The culture was incubated for an additional 4 h at 28 °C. The cells were collected by centrifugation (12,500 rpm) at 4 °C and resuspended in 20 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) lysis buffer with 10 mM protease inhibitor (PMSF, Sigma, USA). The resulting cells were lysed with 30-min sonications (Sonifier 250; Branson Digital Sonifier, Danbury, USA), and the crude cell extracts were centrifuged at 12,500 rpm at 4 °C for 25 min. Soluble proteins containing the PilZLe3639-His6 were collected and mixed with pre-equilibrated Ni2+ resin (GE Healthcare, Shanghai, China) for 1 h at 4 °C. The PilZLe3639-His6 were placed in a column and washed with the re-suspension buffer with 30 mM imidazole. The purified proteins were finally eluted in 250 mM imidazole. The supernatant (soluble proteins containing thePilBLe0708-MBP) was passed through 1 mL amylose resin (New England Biolabs) that retained the PilBLe0708-MBP protein. The column was washed with 200 mL of PBS buffer, and subsequently, 30 mL 10 mM maltose elution buffer was added into the column for protein elution. The protein concentration was determined using a BCA protein assay kit (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China), and the purity was assessed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The GST-Clp fusion protein was purified according to our earlier study (Xu et al. 2018).

Bacterial adenylate cyclase two-hybrid (BACTH) assay

The BACTH system was used to test the direct interactions of two proteins of interest at the E. coli background (Ouellette et al. 2017). In brief, the coding region of PilZLe3639 was cloned into pUT18c to generate the fusion protein comprising PilZLe3639 and the T18 fragment. The coding genes of other test proteins were individually cloned to pKT25 to make each test protein fused with the T25 fragment. Each recombinant pKT25 plasmid along with the pUT18c-PilZLe3639 plasmid were co-transformed into the E. coli BTH101 cells. The resulting E. coli strains were cultivated on LB agar plates with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl β-d-galactopyranoside (X-gal) at 50 μM. The physical interaction of T18 and T25-fused proteins was due to heterodimerization. The latter processs of these hybrid proteins resulted in functional complementation between T25 and T18 fragments, which in turn activate the synthesis of cyclic AMP (cAMP). cAMP binds with the transcription factor CRP to stimulate the transcription of several reporter genes, including genes of the lac operons whose product degrade X-gal resulting in a blue colony formation (Ouellette et al. 2017). The LacZ activity (β-galactosidase activity) was quantified as described previously (Ouellette et al. 2017).

Microscale thermophoresis, MST

The affinity of PilZLe3639-His6 or GST-Clp binding with c-di-GMP was determined by MST, a powerful technique for quantifying the protein-ligand and protein-protein interactions, using Monolith NT.115 (NanoTemper Technologies, Germany) as described previously (Xu et al. 2018; Han et al. 2020). In brief, the purified GST-Clp or PilZLe3639-His6 was labeled with the fluorescent dye NT-647-NHS (Nano Temper Technologies) via amine conjugation. Constant concentration (500 μM) of the labeled target protein in a standard MST buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.05% Tween 20) was titrated against increasing concentrations of c-di-GMP, which were dissolved in diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water. The MST premium-coated capillaries (Monolith NT.115 MO-K005, Germany) were used to load the samples into the MST instrument at 25 °C using 80% MST power, and 20% LED power. FNorm was plotted on a linear y-axis in per mil (‰) against the total concentration of the titrated partner on a log10 x-axis, as reported earlier (Seidel et al. 2013). The experiment was performed in triplicate. Data were analyzed using Nanotemper Analysis software 2.2.4.4577 (NanoTemper Technologies).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- BACTH:

-

Bacterial adenylate cyclase two-hybrid system

- c-di-GMP:

-

Bis-(3′-5′)-cyclic diguanosine monophosphate

- HSAF:

-

Heat-stable antifungal factor

- MST:

-

Microscale thermophoresis

- T4P:

-

Type IV pilus

References

Alm RA, Bodero AJ, Free PD, Mttick JS. Identification of a novel gene, pilZ, essential for type 4 fimbrial biogenesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:46–53.

Burrows LL. Pseudomonas aeruginosa twitching motility: type IV pili in action. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2012;66:493–520..

Carbonnelle E, Helaine S, Prouvensier L, Nassif X, Pelicic V. Type IV pilus biogenesis in Neisseria meningitidis: PilW is involved in a step occurring after pilus assembly, essential for fibre stability and function. Mol Microbiol. 2005;5:54–64.

Chang Y-W, Rettberg LA, Treuner-Lange A, Iwasa J, Søgaard-Andersen L, Jensen GJ. Architecture of the type IVa pilus machine. Science. 2016;351:aad2001.

Chen J, Shen D, Odhiambo BO, Xu D, Han S, Chou S-H, et al. Two direct gene targets contribute to Clp-dependent regulation of type IV pilus-mediated twitching motility in Lysobacter enzymogenes OH11. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2018;102(17):7509–19.

Chen Y, Xia J, Su Z, Xu G, Gomelsky M, Qian G, et al. Lysobacter PilR, the regulator of type IV pilus synthesis, controls antifungal antibiotic production via a c-di-GMP pathway. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2017;83(7):e03397–16.

Chiang P, Sampaleanu LM, Ayers M, Pahuta M, Howell PL, Burrows LL. Functional role of conserved residues in the characteristic secretion NTPase motifs of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa type IV pilus motor proteins PilB, PilT and PilU. Microbiology. 2008;154:114–26.

Christensen P, Cook FD. Lysobacter, a new genus of nonfruiting, gliding bacteria with a high base ratio. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 1978;28:367–93.

Corral J, Sebastià P, Coll NS, Barbé J, Aranda J, Valls M. Twitching and swimming motility play a role in Ralstonia solanacearum pathogenicity. mSphere. 2020;5(2):e00740–19.

Craig L, Forest KT, Maier B. Type IV pili: dynamics, biophysics and functional consequences. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;17:429–40.

de Bruijn I, Cheng X, de Jager V, Expósito RG, Watrous J, Patel N, et al. Comparative genomics and metabolic profiling of the genus Lysobacter. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:991.

Dunger G, Iontop E, Guzzo CR, Farah CS. The Xanthomonas type IV pilus. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2016;30:88–97.

Feng T, Han Y, Li B, Li Z, Yu Y, Sun Q, et al. Interspecies and Intraspecies Signals Synergistically Regulate Lysobacter enzymogenes Twitching Motility. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2019;85(23). https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01742-19.

Galperin MY, Chou SH. Structural conservation and diversity of PilZ-related domains. J Bacteriol. 2020;202(4):e00664–19.

Guzzo CR, Salinas RK, Andrade MO, Farah CS. PilZ protein structure and interactions with PilB and the FimX EAL domain: implications for control of type IV pilus biogenesis. J Mol Biol. 2009;393:848–66.

Han S, Shen D, Wang Y-C, Chou S-H, Gomelsky M, Gao Y-G, et al. A YajQ-LysR-like, cyclic di-GMP-dependent system regulating biosynthesis of an antifungal antibiotic in a crop-protecting bacterium, Lysobacter enzymogenes. Mol Plant Pathol. 2020;21(2):218–29.

Hayward AC, Fegan N, Fegan M, Stirling GR. Stenotrophomonas and Lysobacter: ubiquitous plant-associated gamma-proteobacteria of developing significance in applied microbiology. J Appl Microbiol. 2010;108:756–70.

Huang B, Whitchurch CB, Mattick JS. FimX, a multidomain protein connecting environmental signals to twitching motility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:7068–76.

Jain R, Sliusarenko O, Kazmierczak BI. Interaction of the cyclic-di-GMP binding protein FimX and the type 4 pilus assembly ATPase promotes pilus assembly. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13(8):e1006594.

Kobayashi DY, Reedy RM, Palumbo JD, Zhou J-M, Yuen GY. A clp gene homologue belonging to the Crp gene family globally regulates lytic enzyme production, antimicrobial activity, and biological control activity expressed by Lysobacter enzymogenes strain C3. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:261–9.

Li T-N, Chin K-H, Fung K-M, Yang M-T, Wang AH-J, Chou S-H. A novel tetrameric PilZ domain structure from Xanthomonads. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22036.

Li T-N, Chin K-H, Liu J-H, Wang AH-J, Chou S-H. XC1028 from Xanthamanas campestris adopts a PilZ domain-like structure without a c-di-GMP switch. Proteins. 2009;75:282–8.

McCarthy Y, Ryan RP, O’donovan K, He Y-Q, Jiang B-L, Feng J-X, et al. The role of PilZ domain proteins in the virulence of Xanthomonas campestris pv. Campestris. Mol Plant Pathol. 2008;9:819–24.

Ouellette SP, Karimova G, Davi M, Ladant D. Analysis of membrane protein interactions with a bacterial adenylate cyclase–based two-hybrid (BACTH) technique. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2017;118:20.12.1–20.12.24.

Panthee S, Hamamoto H, Paudel A, Sekimizu K. Lysobacter species: a potential source of novel antibiotics. Arch Microbiol. 2016;198:839–45.

Patel N, Cornejo M, Lambert D, Craig A, Hillman BI, Kobayashi DY. A multifunctional role for the type IV pilus in the bacterial biological control agent Lysobacter enzymogenes (abstract). Phytopathology. 2011;101(6):S138.

Patel N, Hillman B, Kobayashi D. Characterization of type IV pilus in the bacterial biocontrol agent Lysobacter enzymogenes strain C3 (abstract). Phytopathology. 2010;100(6):S98.

Qi Y, Xu L, Dong X, Yau YH, Ho CL, Koh SL, et al. Functional divergence of FimX in PilZ binding and type IV pilus regulation. J Bacteriol. 2012;194(21):5922–31.

Qian G, Hu B, Jiang Y, Liu F. Identification and characterization of Lysobacter enzymogenes as a biological control agent against some fungal pathogens. Agric Sci China. 2009;8(1):68–75.

Qian G, Wang Y, Liu Y, Xu F, He Y-W, Du L, et al. Lysobacter enzymogenes uses two distinct cell-cell signaling systems for differential regulation of secondary-metabolite biosynthesis and colony morphology. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79(21):6604–16.

Qian G, Wang Y, Qian D, Fan J, Hu B, Liu F. Selection of available suicide vectors for gene mutagenesis using chiA (a chitinase encoding gene) as a new reporter and primary functional analysis of chiA in Lysobacter enzymogenes strain OH11. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;28(2):549–57.

Römling U, Galperin MY, Gomelsky M. Cyclic di-GMP: the first 25 years of a universal bacterial second messenger. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2013;77(1):1–52.

Römling U, Gomelsky M, Galperin MY. C-di-GMP: the dawning of a novel bacterial signaling system. Mol Microbiol. 2005;57:629–39.

Seidel SA, Dijkman PM, Lea WA, van den Bogaart G, Jerabek-Willemsen M, Lazic A, et al. Microscale thermophoresis quantifies biomolecular interactions under previously challenging conditions. Methods. 2013;59(3):301–15.

Xia J, Chen J, Chen Y, Qian G, Liu F. Type IV pilus biogenesis genes and their roles in biofilm formation in the biological control agent Lysobacter enzymogenes OH11. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2018;102:833–46.

Xie Y, Wright S, Shen Y, Du L. Bioactive natural products from Lysobacter. Nat Prod Rep. 2012;29:1277–87.

Xu G, Han S, Huo C, Chin K-H, Chou S-H, Gomelsky M, et al. Signaling specificity in the c-di-GMP-dependent network regulating antibiotic synthesis in Lysobacter. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(18):9276–88.

Yu F, Zaleta-Rivera K, Zhu X, Huffman J, Millet JC, Harris SD, et al. Structure and biosynthesis of heat-stable antifungal factor (HSAF), a broad-spectrum antimycotic with a novel mode of action. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:64–72.

Zhao Y, Qian G, Chen Y, Du L, Liu F. Transcriptional and antagonistic responses of biocontrol strain Lysobacter enzymogenes OH11 to the plant pathogenic oomycete Pythium aphanidermatum. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1025.

Zhou X, Qian G, Chen Y, Du L, Liu F, Yuen GY. PilG is involved in the regulation of twitching motility and antifungal antibiotic biosynthesis in the biological control agent Lysobacter enzymogenes. Phytopathology. 2015;105:1318–24.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20190026; BK20181325), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31872016), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (KJJQ202001; KYT201805, KYTZ201403 and KYT202001), Jiangsu Agricultural Sciences and Technology Innovation Fund [CX (18)1003] and Innovation Team Program for Jiangsu Universities (2017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GQ conceived the project. GQ and SH designed experiments. LL, MZ carried out experiments. LL, MZ, DS, SH, and GQ analyzed data and prepared figures and Tables. LL and GQ wrote the manuscript draft. GQ, AMF, and SHC revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study. Table S2. Primers used in this study.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, L., Zhou, M., Shen, D. et al. A non-flagellated biocontrol bacterium employs a PilZ-PilB complex to provoke twitching motility associated with its predation behavior. Phytopathol Res 2, 12 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42483-020-00054-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42483-020-00054-x