Abstract

The receptor-like kinase (RLK) FERONIA functions in immunity in Arabidopsis. Here, we systemically screened rice RLK genes encoding FERONIA-like receptor (FLRs) that may be involved in rice-Magnaporthe oryzae interaction. The expression of 16 FLR genes was examined in response to the infection of M. oryzae in different rice varieties. For each FLR gene, at least two independent mutants were generated by CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing technology in rice variety Zhonghua 11 (ZH11). Blast disease assay identified that the mutants of FLR1 and FLR13 showed increased susceptibility, whereas the mutants of FLR2 and FLR11 displayed enhanced resistance. Consistently, the mutant of FLR1 enhanced, but the mutant of FLR2 delayed the M. oryzae infection progress, which might be associated with the altered expression of defense-related genes. Together, these data indicate that at least 4 FLR genes are involved in rice-M. oryzae interaction and thus are potentially valuable in blast disease resistance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

RLK proteins play vital roles in various biological processes including plant-microbe interactions. When a pathogenic microbe colonizes on the plant surface, the cell membrane-localized RLKs are employed to specifically recognize the cognate pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) via their extracellular domains to activate an innate immunity, termed PAMP-triggered immunity (PTI). For example, the Arabidopsis receptor protein FLAGELLIN-SENSING (FLS2) associates with the co-receptor protein BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE 1–SSOCIATED KINASE 1 (BAK1) in a complex to sense the bacterial PAMP molecule flg22 (Sun et al. 2013). Similarly, the lysin motif-containing receptor proteins LYP4, LYP6, CHITIN ELICITOR RECEPTOR KINASE (CERK1) and CHITIN ELICITOR BINDING PROTEIN (CEBiP) sense the fungal PAMP molecule chitin (Shimizu et al. 2010; Liu et al. 2012). This cognition activates the kinase activity of RLK to transduce the immune signal from the apoplast to the cytoplasm and the nucleus for initiating immune responses, such as the induction of defense-related genes, the activation of mitogen-associated protein kinase (MAPK), H2O2 accumulation, and callose deposition (Bigeard et al. 2015). The successful pathogens secret effector proteins to overcome PTI for pathogenesis (Tsuda and Katagiri 2010). In turn, plants employ resistance (R) proteins to recognize cognate effectors in classic gene-for-gene manner, leading to effector-triggered immunity (ETI).

In Arabidopsis, Catharanthus roseus RLK1-like kinase (CrRLK1L) proteins play vital roles in regulating both PTI and ETI (Mang et al. 2017; Stegmann et al. 2017). For example, FERONIA (FER) is a well-characterized CrRLK1L protein that suppresses resistance to powdery mildew (Kessler et al. 2010), whereas enhances resistance to Pseudomonas syringae tomato DC3000 (Stegmann et al. 2017). FER acts as a scaffold that is required for the assembly of receptor complexes associated with the receptors FLS2, EF-TU RECEPTOR (EFR), and their co-receptor BAK1. Mutation in FER gene leads to the reduction of the ligand-induced assembly of immune receptor complexes FLS2-BAK1 and EFR-BAK1 (Stegmann et al. 2017). Moreover, the FER-scaffold can be inhibited by the binding of a small peptide, RAPID ALKALINIZATION FACTOR 23 (RALF23), which acts as a ligand associated with the extracellular Malectin domain of FER to facilitate infection. Consistently, the transgenic lines over-expressing RALF23 displayed enhanced susceptibility to Pto DC3000 (Stegmann et al. 2017). Another two CrRLK1L proteins, ANXUR1 (ANX1) and ANX2, competitively associate with the co-receptor BAK1 to block the formation of FLS2-BAK1 complex, leading to suppression of FLS2-mediated PTI signaling. ANX1 also associates with RESISTANT TO PSEUDOMONAS SYRINGAE2 (RPS2) to facilitate its protein degradation, leading to compromised ETI responses (Mang et al. 2017).

The functions of CrRLK1L proteins are conserved in cell growth, cell-cell communication and cell wall integrity (CWI) in Arabidopsis and rice (Lindner et al. 2012; Franck et al. 2018). For example, mutations in Arabidopsis FER lead to sterile and growth defection with semi-dwarf, abnormal trichomes, box-shaped epidermal cells, defected root hair (Duan et al. 2010; Li et al. 2015), which can be complemented by exogenous expression of rice DWARF AND RUNTISH SPIKELET1 (DRUS1) gene (Pu et al. 2017). In rice, DRUS1 and DRUS2 are close homologous and confer functions in fertilization and growth similar to those of FERs in Arabidopsis. The drus1 mutant has defection in male gametophyte development and drus1drus2 double mutant has growth defection (Pu et al. 2017). Ruptured Pollen tube (RUPO), a rice ortholog of Arabidopsis ANX1/2, was conservatively required for pollen tube growth and integrity in rice (Liu et al. 2016). However, it is unclear whether rice CrRLK1L genes play roles in rice-M. oryzae interaction.

In rice, there are 16 genes annotated as members of the CrRLK1L gene family in the database of the MSU Rice Genome Annotation Project (http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu/), which are also named FERONIA-like receptors (FLRs) (Li et al. 2016). To identify which of these genes are involved in rice-M. oryzae interaction, we examined their expression upon the infection of M. oryzae in different rice accessions. We also generated mutants for each gene via CRISPR/Cas9 approach and applied them into blast disease assays. Our data indicate that multiple FLR genes are differentially responsive to M. oryzae infection and 4 of them may oppositely regulate rice blast disease resistance, thus provide a start point for further dissecting their functions in rice-M. oryzae interaction.

Results

FLR genes are differentially responsive to M. oryzae infection in different rice accessions

In rice, there are 16 FLR proteins which contain 841–955 amino acid residues (Li et al. 2016). They form five clades in a phylogenetic tree together with 17 homologous members from Arabidopsis (Additional file 1: Figure S1). FLR1/ DRUS1 (DWARF AND RUNTISH SPIKELET 1) and FLR2/ DRUS2 are the closest orthologs to the Arabidopsis FER, whereas FLR6 is close to ANX1 and ANX2 (Additional file 1: Figure S1). To identify which of these 16 FLR protein-encoding genes are involved in rice-M. oryzae interaction, we first analyzed their expressions using RNA-seq data, which were derived from the leaves of a susceptible accession Lijiangxin Tuan Heigu (LTH) and four resistant accessions, including IRBLz5-CA, IRBL9-W, IRBLkm-Ts and YH2115 before and after inoculation with the M. oryzae strain Guy11. YH2115 is an elite restorer line for three-line hybrid rice (Shi et al. 2015). IRBLz5-CA, IRBL9-W and IRBLkm-Ts carry blast resistance gene Pi-2, Pi-9 and Pi-km, respectively (Shi et al. 2015). Apart from FLR6, FLR9, FLR10 and FLR13 that were consistently expressed at the background level, the rest 12 FLR genes exhibited differential responses to M. oryzae infection in at least two accessions (Additional file 1: Figure S2). To confirm this observation, we examined their expression patterns in leaves after inoculation with the M. oryzae strain GZ8 by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). Compared with mock inoculation, eight FLR genes showed differential response patterns between LTH and IRBLkm-Ts upon M. oryzae inoculation, including FLR1, FLR2, FLR5, FLR9, FLR10, FLR11, FLR13 and FLR15 (Fig. 1a), whereas the rest 8 FLR genes showed no significant difference (Fig. 1b). These data indicate that different FLR genes exhibit different responses in different rice accessions to M. oryzae infection.

Expression profiles of FLR genes in rice accessions LTH and IRBLkm-Ts upon M. oryzae inoculation. The seedlings of LTH and IRBLkm-Ts were spray-inoculated with M. oryzae strain GZ8, with ddH2O treatment as mock inoculation. The samples harvested at 0, 12 and 24 hpi for investigating expression profiles of FLR genes. aFLR genes that are responsive to M. oryzae infection. The error bars indicate the mean ±SE (n=3). bFLR genes that are not responsive to M. oryzae infection

FLR mutants were generated by CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing technology

In order to confirm that the M. oryzae-responsive FLR genes are involved, whereas those that are not responsive to M. oryzae are not involved in rice-M. oryzae interaction, we generated knock-out mutants of these FLR genes (named flr-c) respectively by CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing technology in rice cultivar Zhonghua 11 (ZH11) via designing the guide RNA to target the N- terminal sequence of each FLR gene (Additional file 1: Figure S3 and Table 1). Subsequently, we obtained at least two homozygous mutants for each of 13 FLR genes in T1 generation, and for FLR5 and FLR6 in T2 (Additional file 1: Figure S3 and S4). However, we failed to get homozygous mutants for FLR9/RUPO (RUPTURED POLLEN TUBE) (Additional file 1: Figure S4). This is consistent with a previous report that RUPO is critical for male gametophyte transmission and cannot generate homozygous knock-out mutant (Liu et al. 2016). To guarantee that the loss-of-function mutants were obtained, we chose those harboring insertion or deletion to generate a premature stop codon, leading to a large truncation for each FLR gene. For example, flr1-c-1 contains a 2-bp deletion at the gRNA targeting site (Additional file 1: Figure S3), leading to a premature protein with amino acids change started at position 60 and truncated at position 247, whereas, flr1-c-2 includes three types of 1-bp insertion at position 180 (Additional file 1: Figure S3), leading to a same premature protein which has only one amino acid insertion at position 60 in comparison with that in flr1-c-1 (Additional file 1: Figure S4). Four flr2-c mutants have different mutation types that respectively carry 1- and 4-bp deletion, and 1-bp insertion at nucleotide position 277 at the gRNA targeting site (Additional file 1: Figure S3), leading to premature proteins with amino acid change started at position 93 and truncated at position 313 (flr2-c-1), 312 (flr2-c-2) or 243 (flr2-c-3 and -4), respectively (Additional file 1: Figure S4). Besides, we obtained two independent mutants with large truncations at the N-terminus for each of FLR3, FLR4, FLR5, FLR6, FLR7, FLR8, FLR10, FLR12, FLR14, FLR15 and FLR16, three mutants for FLR11, and four mutants for FLR13 (Additional file 1: Figure S3 and S4). These mutants are different from the previously reported ones in mutation site and genetic background (Li et al. 2016; Pu et al. 2017; Yang et al. 2020), and thus should be valuable in functional analysis of FLR genes.

Mutants of 4 FLR genes exhibit altered blast disease resistance phenotypes

To test whether single mutant of each FLR gene influences rice sensitivity to M. oryzae, all the mutants were subjected to blast disease assay by punch-inoculation with the M. oryzae strain GZ8 at the seedling stage. Compared with the disease symptoms on leaves of the wild-type (WT) ZH11, increased lesion size was observed on the leaves of flr1-c-1, flr1-c-2, flr13-c-1 and flr13-c-2 (Fig. 2a, b). Consistently, these mutants supported significantly more fungal growth than their corresponding WT control at 7 days post-inoculation (dpi) (Fig. 2c). In contrast, decreased lesion size was observed on the infected leaves of flr2-c-1, flr2-c-2, flr11-c-1 and flr11-c-2 (Fig. 2a, b), which supported significantly less fungal growth than control at 7 dpi (Fig. 2c). However, similar lesion size and fungal growth were observed on the infected leaves of the other FLR mutants and WT control (Fig. 2). Together, these observations indicate that FLR1 and FLR13 may positively, whereas FLR2 and FLR11 may negatively act in rice resistance to M. oryzae.

Blast disease assay on flr-c mutants. a The typical disease symptoms on leaves of flr-c mutants and their corresponding wild-type ZH11. b, c Lesion length (b) and relative fungal growth (c) were quantified from the inoculated leaves of the indicated rice lines in a. The error bars in b (n=6) and c (n=3) indicate the mean ± SE. The letters indicate the significant difference determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Tukey test (P<0.05)

FLR1 and FLR2 act oppositely in rice resistance against M. oryzae

To confirm that FLR1, FLR2, FLR11 and FLR13 act in rice-M. oryzae interaction, we performed blast disease assay at adult stage by punch-inoculation with the M. oryzae strain GZ8. At the 2-month-old adult stage, punch-inoculation generated bigger disease lesions in mutants of FLR1 and FLR13 than that in WT (Fig. 3a, b), but smaller disease lesions in mutants of FLR2 and FLR11 (Fig. 3a, b). These data indicate that FLR1, FLR2, FLR11 and FLR13 act consistently at both adult and seedling stages.

Four FLR genes affect rice blast resistance. a The representative disease symptoms on leaves of ZH11 and flr-c mutants. b Lesion length was quantified on the inoculated leaves of the indicated rice lines in a. The error bars indicate the mean ±SE (n=6). The letters indicate the significant difference determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Tukey test (P<0.05).c Representative confocal images show the proliferation of M. oryzae hyphae in leaf sheath cells of flr1-c-1, flr2-c-1 and ZH11. a indicates the appressorium. h indicates the invasive hyphae. Scar bar, 20μm. d Quantification analysis of the infection stage at the indicated time points for the rice lines shown in c (n=100)

FLR1 and FLR2 are the closest orthologs to the Arabidopsis FER that regulates vegetative growth and immunity (Deslauriers and Larsen 2010; Stegmann et al. 2017). To explore why they act oppositely in rice-M. oryzae interaction, we compared the infection process of M. oryzae in the mutants flr1-c-1 and flr2-c-1 with that in WT. The leaf sheaths were detached from flr1-c-1, flr2-c-1 and WT at five-leaf seedling stage and inoculated with a GFP-tagged M. oryzae strain GZ8. Under fluorescence microscope, quantification analysis indicated that around 25% spores formed invasive hyphae in the primary infected cells (the first cells) in WT, 55% spores formed invasive hyphae in the first cells and 5% had already expanded to the second cells (the closest neighbor cells of the first cells) in flr1-c-1, but only 10% spores formed invasive hyphae in the first cells in flr2-c-1 at 24 hours post-inoculation (hpi) (Fig. 3c, d). The infection progress was further enhanced in flr1-c-1 at 48 hpi with 50% spores forming invasive hyphae in the third (the second closest neighbors of the first cells) and more cells compared with only 10% in WT. In contrast, only 3% expanded to the second cells and no hyphae in the third and more cells in flr2-c-1 at 48 hpi (Fig. 3c, d). These observations indicate that the infection process of M. oryzae is facilitated in flr1-c-1, but delayed in flr2-c-1. Therefore, FLR1 and FLR2 act oppositely in rice resistance against M. oryzae.

To confirm the roles of FLR1 and FLR2 in rice defense against M. oryzae, we examined the expression of several defense-related genes in spray-inoculated seedlings of flr1-c-1, flr1-c-2, flr2-c-1 and flr2-c-2 in comparison with that of WT. Disease symptoms and fungal growth were shown at 5 dpi of the blast fungus (Fig. 4a, b). The expression of three defense-related genes was examined at 24 hpi, including OsNAC4, PBZ1 and PR10b, which are often used as immune markers. OsNAC4 encodes a transcription factor that positively regulates hypersensitive response (HR) cell death (Kaneda et al. 2009). PBZ1 is a PR10 family gene associated with cell death (Kim et al. 2011). PR10b was induced by M. oryzae infection (McGee et al. 2001) and often used as a marker to monitor rice immune response (Zhao et al. 2019). OsNAC4, PBZ1 and PR10b were up-regulated in all tested lines at 24 hpi with the M. oryzae strain GZ8 compared with that in mock inoculated samples (Fig. 4c-e). However, their expressions were lower in flr1-c-1, but higher in flr2-c-1 than in ZH11 (Fig. 4c-e), indicating that flr1-c-1 is more susceptible, and flr2-c-1 is more resistant to M. oryzae than ZH11.

FLR1 and FLR2 oppositely act in rice blast resistance. a Spray-inoculated disease symptoms of rice blast disease on the indicated rice lines. b Relative fungal growth was quantified on the inoculated leaves of the indicated rice lines in a. Expression of NAC4 (c), PBZ1 (d) and PR10b (e) were measured in flr1-c-1, flr2-c-1 and ZH11 at 0 and 24 hpi and normalized by OsUbi. The error bars indicate the mean ±SE (n=3). The letters indicate the significant difference determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Tukey test (P<0.05)

Together, these data indicate that FLR1 positively, but FLR2 negatively act in resistance to M. oryzae.

Discussion

In this study, we systemically screened rice FLR genes to identify those that may play roles in rice-M. oryzae interaction. RNA-seq data showed that 12 out of 16 FLR genes were differentially expressed among five rice accessions upon M. oryzae infection (Additional file 1: Figure S2), and of these, eight were confirmed to be differentially responsive to infection of M. oryzae between a susceptible and a resistant rice accession (Fig. 1). More than 30 mutants were subsequently generated via CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing technology, which included at least two independent mutants for each of 15 FLR genes (Fig. 2 and Additional file 1: Figure S4). Mutants of 4 FLR genes displayed altered sensitivity to M. oryzae, of which flr1-c-1, flr1-c-2, flr13-c-1 and flr13-c-2 showed increased, whereas flr2-c-1, flr2-c-2, flr11-c-1 and flr11-c-2 showed decreased sensitivity (Fig. 2, Fig. 3 and Fig. 4). Our data are consistent with a recent report on the roles of 14 FLR genes in rice-M. oryzae interaction with a background of Nipponbare (Yang et al. 2020). Therefore, at least 4 FLR genes were identified to be involved in rice-M. oryzae interaction, of which FLR1 and FLR13 positively, whereas FLR2 and FLR11 negatively act in rice blast disease resistance.

Through gene expression analysis and rice blast resistance investigation, we found some FLR genes that are responsive to M. oryzae infection don’t affect disease symptom. However, we still can’t completely rule out the possibility that these FLR genes act in rice blast disease resistance. One reason could be that gene expression might be age-dependent or rice accession-specific. This can explain the difference between RNA-seq and qRT-PCR data on detection of M. oryzae-responsive genes. Since there are no different disease phenotypes between the mutants of M. oryzae-responsive genes and their corresponding wild-type strain, these genes may play a subtle role in response to M. oryzae. Alternatively, since these genes are phylogenetically closely related, they may act redundantly, and single mutant could not exhibit obvious phenotype. In the phylogenetic tree, FLR3 is closely related with FLR4 and FLR5, FLR7 with FLR8, and FLR14 with FLR15 and FLR16 (Additional file 1: Figure S1). Functional redundancy is common in closely related genes. For example, Arabidopsis ANX1 is closely related with ANX2, and they function redundantly to maintain cell wall integrity of pollen tube before reaching the female gametophytes (Boisson-Dernier et al. 2009; Miyazaki et al. 2009). Rice FLR1/DRUS1 and FLR2/DRUS2 also have redundant functions in reproductive growth and development (Pu et al. 2017), although they act oppositely in response to M. oryzae (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4). Therefore, future work should construct double and/or triple mutants to exclude the involvement of other FLR genes in rice-M. oryzae interaction. It is intriguing that FLR1 and FLR2 act oppositely in rice-M. oryzae interaction because both are the closest orthologs to the Arabidopsis FER and are in the same clade (Additional file 1: Figure S1). This may be a common phenomenon existing in some homologous proteins that are involved in plant immunity. In Arabidopsis, three CrRLK1L proteins, FER, ANX1 and ANX2, play antagonistic roles in immunity against bacterium pathogens, although they are in the same clade (Additional file 1: Figure S1). Compared with its corresponding WT, fer mutants showed increased susceptibility (Stegmann et al. 2017), but anx mutants showed enhanced resistance to Pst DC3000 (Mang et al. 2017). FER functions as a scaffold protein to facilitate, but ANX1 and ANX2 function as competitors to interfere with the formation of ligand-induced receptor complex (Franck et al. 2018). The similar phenomenon has also been reported for some homologous resistance proteins. For example, rice Pigm-R and Pigm-S, two homologous proteins encoded by two genes clustered at the Pigm locus, act antagonistically in blast disease resistance and yield traits (Deng et al. 2017). Pigm-S specifically expressed in panicle promotes seed setting and compensates the yield decrease caused by Pigm-R. Ectopic expression of Pigm-S competitively associates with Pigm-R, suppressing the formation of the Pigm-R homodimer to attenuate disease resistance. These results uncovered that the proper-spatiotemporal gene expression facilitates the balance between plant growth and resistance (Deng et al. 2017). Yang et al. (2020) recently reported that the expression of 4 FLR genes exhibited tissue specificity (Yang et al. 2020), implying that spatiotemporal gene expression may be employed by FLRs for properly performing their function. Therefore, one focus of the future research should be on how different FLR genes are spatiotemporally regulated upon the infection of M. oryzae.

It is a challenging question whether rice FLR receptors recognize RALF peptides to regulate rice-M. oryzae interaction, although RALF peptides have been characterized as the ligand for CrRLK1L proteins to modulate plant growth and immunity (Stegmann et al. 2017; Zhong and Qu 2019). RALF peptides exist in both plants and pathogenic microbes and act as signal peptides for regulating plant growth, and plant-microbe interactions (Masachis et al. 2016; Stegmann et al. 2017). For example, a RALF from Fusarium oxysporum binds FER to regulate immune signal for pathogenesis (Masachis et al. 2016). The RALF orthologs widely exist in 26 species of phytopathogenic fungi (Thynne et al. 2017). We examined the genome of three M. oryzae strains (i.e. 70–15, Y34 and P131), but failed to identify any RALF orthologs. Therefore, M. oryzae may not exploit RALF to facilitate pathogenesis. Instead, other signal peptides secreted by M.oryzae or rice endogenous RALF peptides may act as the FLR’s ligands to activate signal transductions. According to this speculation, the future work will focus on identification of RALFs or other potential ligand proteins that associate with different FLRs and dissection of their roles in rice-M. oryzae interaction.

Conclusions

Out of 16 CrRLK1L family genes that are named FLRs, we identified 8 genes that are differentially responsive to M. oryzae infection. After generating mutants for 15 FLR genes and applying them in blast disease assays, we identified that 4 of them act in rice-M. oryzae interaction. Thus, our data provide a start point to dissect the roles of FLRs in the regulation of rice immunity against M. oryzae.

Methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

The rice accessions include two Oryza sativa L. ssp. japonica varieties, i.e. LTH and ZH11, and four O. sativa L. ssp. indica varieties, i.e. IRBLz5-CA, IRBL9-W, IRBLkm-Ts and YH2115. Mutants were generated from the ZH11 background using CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing technology. Rice plants were grown in the paddy field in Wenjiang District, Chengdu City, Sichuan Province, China during summer and grown in the paddy field in Lingshui County, Hainan Province, China during winter. The rice seedlings used in this study were grown in a greenhouse with a temperature of 28 ± 2 °C, relative humidity of 70%, and photoperiod of 12h light/12h dark.

Generation of mutants

The guide RNAs (gRNAs) targeting each FLR gene were selected using the E-CRISP Design Tool (http://www.e-crisp.org) (Heigwer et al. 2014). The primers were designed following the user manual of the EXclone cloning vector (Biogle Co., Ltd). The primer pair was aligned to form a short fragment with sticky ends, which was directly ligated with EX-Vector to generate the constructs of EX-Vector-FLR-1 to -16. The transgenic rice lines were generated from the ZH11 background by Agrobacterium-mediated transformation as described previously (Toki 1997). The transgenic lines were firstly screened on MS medium with 50 μg/L hygromycin. The positive lines were genotyped by primer pair across the gRNA target site. The PCR products were analyzed by Sanger sequencing to identify the positive transgenic plants with a null mutation at the gRNA target site.

Rice blast disease assay

The GFP-tagged M. oryzae strain GZ8 was used in this study for rice blast disease assay and infection process investigation. The strain was cultured for 10 days on oatmeal and tomato media (OTA) in a growth chamber with a temperature of 28 °C and a photoperiod of 12 h light/12 h dark for hyphae growth. At 10 days later, the hyphae were scratched and the cultures were then incubated for sporulation at 28 °C under 24 h continuous light condition. The spores were harvested with ddH2O 4 days later and purified through nylon mesh. Finally, the spore concentration was adjusted to 5 × 105 conidia/mL for drop- and spray-inoculation.

For disease assay, six detached leaves from each rice line were punch-inoculated with M. oryzae following a previous study (Park et al. 2012). The biggest lesion in each leaf was measured by the software ImageJ for lesion length quantification. The relative fungal growth was indicated by the DNA amount ratio of M. oryzaePot2 to rice OsUbi. measured by quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) (Li et al. 2019). The primers of MoPot2 RT-F: ACGACCCGTCTTTACTTATTTGG, MoPot2 RT-R: AAGTAGCGTTGGTTTTGTTGGAT and Ubi RT-F: GCCCAAGAAGAAGATCAAGAAC, Ubi RT-R: AGATAACAACGGAAGCATAAAAGTC were used for qRT-PCR to quantify DNA amount of M. oryzae Pot2 and OsUbi, respectively. Three independent repeats are performed in each assay.

The leaf sheaths were detached from 1-month-old seedlings for investigation of M. oryzae infection process. The infection process was observed and recorded at 24 and 48 hpi under a laser scanning confocal microscope (LSCM). 100 single-spore penetration sites were recorded for calculating the infection process in each rice line.

RNA isolation and gene expression analysis

One-month-old seedlings were spray-inoculated with the M. oryzae strain GZ8 (1 × 105 conidia/mL) or ddH2O (mock inoculation). The samples were harvested at 0, 12 and 24 hpi. Total RNA isolation and cDNA reverse transcription were performed following the manufacturer’s instructions of TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and PrimeScript™ RT reagent Kit, respectively. SYBR Green mix (QuantiNova SYBR Green PCR Kit, Qiagen) was used for the qRT-PCR assay with the primers of OsNAC4 RT-F: TCCTGCCACCATTCTGAGATG and OsNAC4 RT-R: TTGCAGAATCATGCTTGCCAG, OsPR10b-RT-F: AACACGTGTGGTGGCACGTG and OsPR10b-RT-R: TCATCTTGAGCATGCCGAAG, OsPBZ1-RT-F: ACACCATGAAGCTTAACCCTGG and OsPBZ1-RT-R: TCGAGTGTGACTTGAGCTTCC, Ubi RT-F: GCCCAAGAAGAAGATCAAGAAC and Ubi RT-R: AGATAACAACGGAAGCATAAAAGTC to investigate the expression profiles of NAC4, PR10b, PBZ1 and OsUbi, respectively. The rice Ubiquitin (OsUbi) gene was used as an internal reference.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ANX:

-

ANXUR

- BAK1:

-

BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE 1–ASSOCIATED KINASE 1

- CrRLK1L:

-

Catharanthus roseus RLK1-like kinase

- DRUS1:

-

DWARF AND RUNTISH SPIKELET 1

- EFR:

-

EF-TU RECEPTOR

- ETI:

-

Effector-triggered immunity

- FER:

-

FERONIA

- FLR:

-

FERONIA-like receptor

- flr-c :

-

Knock-out mutants of FLR genes generated by CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing technology

- FLS2:

-

FLAGELLIN-SENSING

- gRNA:

-

Guide RNA

- HR:

-

Hypersensitive response

- LSCM:

-

Laser scanning confocal microscope

- LTH:

-

Lijiangxin Tuan Heigu

- LYPs:

-

LYSIN MOTIF-CONTAINING PROTEINS

- M. oryzae :

-

Magnaporthe oryzae

- MAPK:

-

Mitogen-associated protein kinase

- CEBiP:

-

CHITIN ELICITOR BINDING PROTEIN

- OsCERK1:

-

CHITIN ELICITOR RRECEPTOR KINASE 1

- OsUbi :

-

Rice ubiquitin

- OTA:

-

Oatmeal and tomato media

- PAMPs:

-

Pathogen-associated molecular patterns

- PTI:

-

PAMP-triggered immunity

- R protein:

-

Resistance protein

- RALF23:

-

RAPID ALKALINIZATION FACTOR 23

- RLK:

-

Receptor-like kinase

- RPS2:

-

RESISTANT TO PSEUDOMONAS SYRINGAE 2

- RT-PCR:

-

Real-time fluorescent quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- RUPO:

-

RUPTURED POLLEN TUBE

- ZH11:

-

Zhonghua11

References

Bigeard J, Colcombet J, Hirt H. Signaling mechanisms in pattern-triggered immunity (PTI). Mol Plant. 2015;8:521–39.

Boisson-Dernier A, Roy S, Kritsas K, Grobei MA, Jaciubek M, Schroeder JI, et al. Disruption of the pollen-expressed FERONIA homologs ANXUR1 and ANXUR2 triggers pollen tube discharge. Development. 2009;136:3279–88.

Deng Y, Zhai K, Xie Z, Yang D, Zhu X, Liu J, et al. Epigenetic regulation of antagonistic receptors confers rice blast resistance with yield balance. Science. 2017;355:962–5.

Deslauriers SD, Larsen PB. FERONIA is a key modulator of brassinosteroid and ethylene responsiveness in Arabidopsis hypocotyls. Mol Plant. 2010;3:626–40.

Duan Q, Kita D, Li C, Cheung AY, Wu H-M. FERONIA receptor-like kinase regulates RHO GTPase signaling of root hair development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:17821–6.

Franck CM, Westermann J, Boisson-Dernier A. Plant malectin-like receptor kinases: from cell wall integrity to immunity and beyond. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2018;69:301–28.

Heigwer F, Kerr G, Boutros M. E-CRISP: fast CRISPR target site identification. Nat Methods. 2014;11:122–3.

Kaneda T, Taga Y, Takai R, Iwano M, Matsui H, Takayama S, et al. The transcription factor OsNAC4 is a key positive regulator of plant hypersensitive cell death. EMBO J. 2009;28:926–36.

Kessler SA, Shimosato-Asano H, Keinath NF, Wuest SE, Ingram G, Panstruga R, et al. Conserved molecular components for pollen tube reception and fungal invasion. Science. 2010;330:968–71.

Kim SG, Kim ST, Wang Y, Yu S, Choi IS, Kim YC, et al. The RNase activity of rice probenazole-induced protein1 (PBZ1) plays a key role in cell death in plants. Mol Cells. 2011;31:25–31.

Li C, Wang L, Cui Y, He L, Qi Y, Zhang J, et al. Two FERONIA-like receptor (FLR) genes are required to maintain architecture, fertility, and seed yield in rice. Mol Breed. 2016;36:151.

Li C, Yeh FL, Cheung AY, Duan Q, Kita D, Liu M-C, et al. Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins as chaperones and co-receptors for FERONIA receptor kinase signaling in Arabidopsis. eLIFE. 2015;4:e06587.

Li Y, Cao X-L, Zhu Y, Yang X-M, Zhang K-N, Xiao Z-Y, et al. Osa-miR398b boosts H2O2 production and rice blast disease-resistance via multiple superoxide dismutases. New Phytol. 2019;222:1507–22.

Lindner H, Müller LM, Boisson-Dernier A, Grossniklaus U. CrRLK1L receptor-like kinases: not just another brick in the wall. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2012;15:659–69.

Liu B, Li J-F, Ao Y, Qu J, Li Z, Su J, et al. Lysin motif–ontaining proteins LYP4 and LYP6 play dual roles in peptidoglycan and chitin perception in rice innate immunity. Plant Cell. 2012;24:3406–19.

Liu L, Zheng C, Kuang B, Wei L, Yan L, Wang T. Receptor-like kinase RUPO interacts with potassium transporters to regulate pollen tube growth and integrity in rice. PLoS Genet. 2016;12:e1006085.

Mang H, Feng B, Hu Z, Boisson-Dernier A, Franck CM, Meng X, et al. Differential regulation of two-tiered plant immunity and sexual reproduction by ANXUR receptor-like kinases. Plant Cell. 2017;29:3140–56.

Masachis S, Segorbe D, Turrà D, Leon-Ruiz M, Fürst U, El Ghalid M, et al. A fungal pathogen secretes plant alkalinizing peptides to increase infection. Nat Microbiol. 2016;1:16043.

McGee JD, Hamer JE, Hodges TK. Characterization of a PR-10 pathogenesis-related gene family induced in rice during infection with Magnaporthe grisea. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2001;14:877–86.

Miyazaki S, Murata T, Sakurai-Ozato N, Kubo M, Demura T, Fukuda H, et al. ANXUR1 and 2, sister genes to FERONIA/SIRENE, are male factors for coordinated fertilization. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1327–31.

Park C-H, Chen S, Shirsekar G, Zhou B, Khang CH, Songkumarn P, et al. The Magnaporthe oryzae effector AvrPiz-t targets the RING E3 ubiquitin ligase APIP6 to suppress pathogen-associated molecular pattern–riggered immunity in rice. Plant Cell. 2012;24:4748–62.

Pu C-X, Han Y-F, Zhu S, Song F-Y, Zhao Y, Wang C-Y, et al. The rice receptor-like kinases DWARF AND RUNTISH SPIKELET1 and 2 repress cell death and affect sugar utilization during reproductive development. Plant Cell. 2017;29:70–89.

Shi J, Li D, Li Y, Li X, Guo X, Luo Y, et al. Identification of rice blast resistance genes in the elite hybrid rice restorer line Yahui2115. Genome. 2015;58:91–7.

Shimizu T, Nakano T, Takamizawa D, Desaki Y, Ishii-Minami N, Nishizawa Y, et al. Two LysM receptor molecules, CEBiP and OsCERK1, cooperatively regulate chitin elicitor signaling in rice. Plant J. 2010;64:204–14.

Stegmann M, Monaghan J, Smakowska-Luzan E, Rovenich H, Lehner A, Holton N, et al. The receptor kinase FER is a RALF-regulated scaffold controlling plant immune signaling. Science. 2017;355:287–9.

Sun Y, Li L, Macho AP, Han Z, Hu Z, Zipfel C, et al. Structural basis for flg22-induced activation of the Arabidopsis FLS2-BAK1 immune complex. Science. 2013;342:624–8.

Thynne E, Saur IML, Simbaqueba J, Ogilvie HA, Gonzalez-Cendales Y, Mead O, et al. Fungal phytopathogens encode functional homologues of plant rapid alkalinization factor (RALF) peptides. Mol Plant Pathol. 2017;18:811–24.

Toki S. Rapid and efficient agrobacterium-mediated transformation in rice. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 1997;15:16–21.

Tsuda K, Katagiri F. Comparing signaling mechanisms engaged in pattern-triggered and effector-triggered immunity. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2010;13:459–65.

Yang Z, Xing J, Wang L, Liu Y, Qu J, Tan Y, et al. Mutations of two FERONIA-like receptor genes enhance rice blast resistance without growth penalty. J Exp Bot. 2020;71:2112–26.

Zhao Z-X, Feng Q, Cao X-L, Zhu Y, Wang H, Chandran V, et al. Osa-miR167d facilitates infection of Magnaporthe oryzae in rice. J Integr Plant Biol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1111/jipb.12816.

Zhong S, Qu L-J. Peptide/receptor-like kinase-mediated signaling involved in male-female interactions. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2019;51:7–14.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31901839 and U19A2033) and a grant from Sichuan Agricultural University (1922996003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y-YH and W-MW conceived the project. Y-YH and X-XL designed and performed most of the experiments with support from YX, X-YL, Z-JH, L-FW, W-QD, L-LZ, J-QZ J-WZ, YL and JF. Y-YH, X-XL, YX, X-YL, HW, YZ, HF and MP grew the plants and harvested the samples. Y-YH, X-XL and W-MW wrote the manuscript. Y-YH, X-XL contributed equally to this work. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

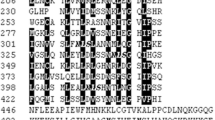

A phylogenetic tree of CrRLK1L family proteins. The full-length protein sequences were aligned by ClustalW and then generated the phylogenetic tree by the UPGMA method with 1000 bootstrap replicates in MEGA-X. This phylogenetic tree contains 33 CrRLK1L family members in Arabidopsis and rice. In rice, the CrRLK1L-encoding genes were named as FERONIA-like receptors (FLRs). Figure S2. RNA-seq heatmap of FLR genes in LTH and four resistant rice accessions upon M. oryzae infection. The 4-week-old seedlings of the indicated rice accessions were spray-inoculated with the M. oryzae strain Guy11. The samples were harvested for RNA-seq analysis at 0, 12, 24 hpi. Figure S3. DNA sequence of each flr-c mutant. The DNA sequence of the indicated homozygous mutants was identified by sequencing. The schematic diagram indicates the structure of FLR gene. The blue box indicates gene exon. The red triangle indicates the gRNA target site which corresponds to the red portion of the sequence below the schematic diagram. The black letters in red portion indicate inserted bases. The black dotted line fills up the gap caused by base deletion. The red dotted line fills up the gap between two adjacent bases without deletion. Figure S4. The truncated peptides encoded by mutated FLR genes. The proteins encoded by wild-type genes from ZH11 and mutated FLR genes were aligned by online multiple alignment tool (http://multalin.toulouse.inra.fr/multalin/). Red portion indicates the same protein sequence for both ZH11 and mutants. The blue or black portion indicates the mutated sequence after the mutation site in flr-c mutants. The black star indicates the ending site of protein encoded by mutated FLR gene.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, YY., Liu, XX., Xie, Y. et al. Identification of FERONIA-like receptor genes involved in rice-Magnaporthe oryzae interaction. Phytopathol Res 2, 14 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42483-020-00052-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42483-020-00052-z