Abstract

Background

Carvedilol is one of the most effective beta-blockers in reducing ventricular tachyarrhythmias and mortality in patients with heart failure. One of the possible antiarrhythmic mechanisms of carvedilol is the suppression of store overload-induced Ca2+ release, especially for the triggered activity.

Objectives

Premature ventricular complex (PVC) originating from the ventricular outflow tract (OT) is the most common form of idiopathic PVC, and its main mechanism is related to triggered activity. We evaluate the efficacy of carvedilol to suppress the OT PVC.

Methods

The electronic medical records at our hospital were screened to identify OT PVC patients treated with carvedilol. Clinical, electrocardiographic, and Holter monitoring studies were reviewed.

Results

A total of 25 patients who underwent Holter monitoring before and after carvedilol administration were found and enrolled. The mean age of the patients was 54.9 ± 13.9 years, and the mean dose of carvedilol was 18.2 ± 10.2 mg (sustained release formulation, 8/16/32 mg). The 24-h burden of PVC in 18 (72%) of 25 patients was significantly reduced from 12.2 ± 9.7% to 4.4 ± 6.7% (P = 0.006). In seven patients, the burden of PVC was changed from 7.1 ± 6.1% to 9.8 ± 8.4% (P = 0.061). There was no difference in age, carvedilol dose, duration of treatment, ventricular function, and left atrial size between responding and non-responding groups.

Conclusion

In this retrospective pilot study, treatment with carvedilol showed PVC suppression in 72% of patients. Now, we are conducting a prospective, randomized, multicenter study to evaluate the effect of carvedilol on OT PVC (Clinical trial registration: FOREVER trial, Clinical-Trials.gov: NCT03587558).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Carvedilol is one of the most effective beta-blockers to reduce ventricular arrhythmia and mortality in patients with heart failure [1, 2]. Antioxidative and alpha-blockade effects, along with nonselective beta-blockade, have been proposed, but the exact mechanism is still unknown. Recently, inhibition of store overload-induced calcium release (SOICR) has been suggested as an antiarrhythmic effect of carvedilol [3]. The SOICR may cause significant arrhythmia by the triggered activity, which is induced by activating the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger. Among various beta-blockers, only carvedilol is known to be a drug that can directly inhibit the release of SOICR along with the beta-blockade effect. Premature ventricular complex (PVC) occurring in the ventricular outflow tract (OT) is the most common arrhythmia among the idiopathic ventricular arrhythmias (VAs), and its mechanism is related to intracellular calcium overload and delayed afterdepolarizations that leads to triggered activity [4]. The OT PVCs associated with disruptive symptoms and frequent OT PVCs can lead to cardiomyopathy. Therefore, the OT PVC often requires treatment. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effect of carvedilol on patients with OT PVC as a retrospective study and to obtain basic data for the future prospective randomized study.

Methods

Patients who had a diagnosis of “ventricular premature complex (I49.3 in ICD-10)” were retrospectively identified by systematic screening of the Keimyung University Dongsan Hospital electronic medical records review. A manual chart review was performed on this subset of patients to identify those who were prescribed carvedilol for the treatment of OT PVC. The OT PVC was defined as PVC showing a tall R wave in II/III/aVF lead in the 12-lead electrocardiogram. Of these, patients treated with carvedilol and who underwent Holter monitoring before and after treatment were identified. Clinical, electrocardiographic, and Holter monitoring studies were reviewed and analyzed.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as the mean value ± standard deviation. The median and interquartile range were used for continuous variables that did not follow a normal distribution. Categorical variables are expressed as numbers and percentages. To compare the continuous variables, paired or independent sample t test was performed. For categorical variables, the Chi-square test was used. All statistical analyses were performed by the MedCalc statistical software version 19.1.7 (MedCalc Software Ltd, Ostend, Belgium). A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study population

A total of 25 patients were reviewed and analyzed. The baseline characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. The mean age of the patients was 54.3 ± 12.4 years, and eight patients (32%) were male. All patients had structurally normal hearts, and a mean LV ejection fraction was 64.5 ± 5.0%. The enrolled patients in our study did not have significant comorbidities, and all patients did not take concomitant medications that would affect the PVC burden.

Treatment results

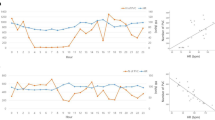

The sustained release formulation of carvedilol was prescribed in all patients, and the mean dosage was 18.2 ± 10.2 mg (9 patients on 8 mg, 8 patients on 16 mg, 8 patients on 32 mg). The average duration of carvedilol treatment was 158.3 ± 92.1 days. After carvedilol use, the maximal heart rate was reduced significantly (Table 2). The mean baseline 24-h PVC burden on Holter monitoring was 10.8% ± 9.0% (interquartile range (IQR), 3.3–15.8%), and it was decreased to 5.9% ± 7.4% after carvedilol treatment (P = 0.007, Fig. 1). This suppression of PVC was observed in 18 (72%) patients (12.2 ± 9.7–4.4% ± 6.7%, average 7.8% ± 7.6% reduction in PVC burden, P = 0.006). Symptom improvement was observed in 15 (60%) patients.

Comparison between patients with reduced PVC group and not-reduced group

The burden of PVC was not reduced in seven patients (7.1 ± 6.1–9.8% ± 8.4, P = 0.061). There was no difference in baseline clinical characteristics between carvedilol treatment responding and non-responding groups (Table 3). In patients with PVC reduction, maximal heart rate was also significantly reduced (Additional file 1: Supplement Table 1).

Effect of carvedilol according to dosage

The degree of PVC suppression according to carvedilol dosage was as follows: − ∆1.9% ± 3.7% in 8 mg group, − ∆7.0% ± 9.7% in 16 mg group, − ∆6.0% ± 10.1 in 32 mg group. The comparison between three groups on the degree of PVC suppression did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.098, using ANOVA, Scheffe test). Figure 2 illustrates the mean 24-h PVC burden on Holter monitoring before and after carvedilol use according to dosage.

Discussion

In this cohort of 25 patients with OT PVC, carvedilol treatment significantly reduced the PVC burden. Overall, 72% of patients showed a decrease in PVC, and the average reduced burden of PVC compared to baseline was 71.5% ± 32.3%.

The mechanism underlying the favorable antiarrhythmic effect of carvedilol remains unclear. The antioxidant and alpha-blocking activities of carvedilol have been suggested to contribute to its beneficial effects, but those were not corroborated by clinical studies [5, 6]. Recently, inhibition of SOICR has been suggested as an antiarrhythmic effect of carvedilol [3]. Stimulation of the beta-receptor leads to the entry of calcium into the cell by opening the L-type calcium channel. The influx of calcium through the L-type calcium channel also increases calcium release from SR (sarcoplasmic reticulum) through the ryanodine receptor (RyR). This Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release is essential to muscle contraction as a normal function. However, in the event of SR calcium overloading or excessive beta-adrenergic receptor stimulation, spontaneous calcium release, which is not associated with the depolarization, known as SOICR, can occur through the RyR. This phenomenon may cause severe arrhythmia of triggered activity by activating the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger. Indeed, SOICR-evoked delayed afterdepolarizations (DADs) cause catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, which is associated with naturally occurring RyR2 mutations [7, 8]. Among various beta-blockers, only carvedilol is known to be a drug that can directly inhibit the release of SOICR along with the beta-blockade effect [3].

One of the major limitations of using carvedilol for anti-SOICR effect is its dose. The concentrations of carvedilol required to suppress SOICR (0.3–1 μM) are much higher than those required for beta-blockade (~ 1 nM) [9]. Therefore, strong SOICR inhibition would require high doses of carvedilol, which could produce excessive beta-blockade and accompanying adverse effects such as bradycardia [10]. However, it has been reported that carvedilol has a high degree of lipophilicity and shows a large volume of distribution, so it accumulates at a higher concentration in the cardiac muscle than in plasma [11,12,13]. In addition, the longer the exposure to carvedilol, the smaller the dose of carvedilol can inhibit SOICR [3]. Pharmacologically, separating the beta-blocking and anti-SOICR activities of carvedilol could be one solution [3]. In our study, carvedilol is thought to have a higher effect on suppressing PVC at 16 mg or more than 8 mg. In addition, comparisons of electrocardiographic and Holter monitoring parameters before and after carvedilol use according to dosage showed a tendency of dose-dependent response in suppressing maximal heart rate (Additional file 1: Supplement Table 2). However, 8 mg of carvedilol also showed a significant decrease in maximal heart rate. Further studies are needed to conclude optimal dosage and inter-individual difference of carvedilol to suppress the PVC.

The VAs most frequently occur in patients with structural heart disease. However, some VAs can occur in patients without structural heart disease and those are called idiopathic VAs. The most common origins of idiopathic VAs are the right and left ventricular outflow tracts [14]. The idiopathic VAs are thought to be caused by catecholamine-induced, cyclic adenosine monophosphate–mediated DADs and triggered activity [15].

Under this background, we hypothesized that carvedilol, which can reduce triggered activity by inhibiting SOICR, would be effective for OT PVC. To confirm this hypothesis, we designed this retrospective study and the results were impressive. Now, we are conducting a prospective, randomized, multicenter study to evaluate the effect of carvedilol on OT PVC (FOREVER trial, Clinical-Trials.gov: NCT 03587558) and are expecting the results.

Our study has some limitations. The main problem is the small number of total patients and retrospective study design for the conclusion. In one in vitro study, carvedilol is the only beta-blocker tested that can effectively suppress SOICR [3]. However, the effect of carvedilol should be tested in vivo study with other beta-blockers such as bisoprolol and metoprolol and also with placebo.

Conclusion

In our retrospective, pilot study, carvedilol showed good efficacy for suppressing OT PVCs. Large, prospective, randomized studies are needed to demonstrate the effect of carvedilol on PVC suppression.

Abbreviations

- SOICR:

-

store overload-induced calcium release

- PVC:

-

premature ventricular complex

- OT:

-

ventricular outflow tract

- VA:

-

ventricular arrhythmia

- DAD:

-

delayed afterdepolarizations

- RyR:

-

ryanodine receptor

References

Poole-Wilson PA, Swedberg K, Cleland JG, Di Lenarda A, Hanrath P, Komajda M, et al. Comparison of carvedilol and metoprolol on clinical outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure in the Carvedilol Or Metoprolol European Trial (COMET): randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;362(9377):7–13.

McMurray J, Kober L, Robertson M, Dargie H, Colucci W, Lopez-Sendon J, et al. Antiarrhythmic effect of carvedilol after acute myocardial infarction: results of the Carvedilol Post-Infarct Survival Control in Left Ventricular Dysfunction (CAPRICORN) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(4):525–30.

Zhou Q, Xiao J, Jiang D, Wang R, Vembaiyan K, Wang A, et al. Carvedilol and its new analogs suppress arrhythmogenic store overload-induced Ca2+ release. Nat Med. 2011;17(8):1003–9.

Lerman BB. Mechanism, diagnosis, and treatment of outflow tract tachycardia. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015;12(10):597–608.

Stroe AF, Gheorghiade M. Carvedilol: beta-blockade and beyond. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2004;5(Suppl 1):S18–27.

Remme WJ. Which beta-blocker is most effective in heart failure? Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2010;24(4):351–8.

Jiang D, Xiao B, Yang D, Wang R, Choi P, Zhang L, et al. RyR2 mutations linked to ventricular tachycardia and sudden death reduce the threshold for store-overload-induced Ca2+ release (SOICR). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(35):13062–7.

Jiang D, Wang R, Xiao B, Kong H, Hunt DJ, Choi P, et al. Enhanced store overload-induced Ca2+ release and channel sensitivity to luminal Ca2+ activation are common defects of RyR2 mutations linked to ventricular tachycardia and sudden death. Circ Res. 2005;97(11):1173–81.

Yao A, Kohmoto O, Oyama T, Sugishita Y, Shimizu T, Harada K, et al. Characteristic effects of α1-β1,2-adrenergic blocking agent, carvedilol, on [Ca2+]i in ventricular myocytes compared with those of timolol and atenolol. Circ J. 2003;67(1):83–90.

Ko DT, Hebert PR, Coffey CS, Curtis JP, Foody JM, Sedrakyan A, et al. Adverse effects of beta-blocker therapy for patients with heart failure: a quantitative overview of randomized trials. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(13):1389–94.

Caron G, Steyaert G, Pagliara A, Reymond F, Crivori P, Gaillard P, et al. Structure-lipophilicity relationships of neutral and protonated β-blockers, part I, intra- and intermolecular effects in isotropic solvent systems. Helv Chim Acta. 1999;82(8):1211–22.

Fujimaki M. Stereoselective disposition and tissue distribution of carvedilol enantiomers in rats. Chirality. 1992;4(3):148–54.

Stahl E, Mutschler E, Baumgartner U, Spahn-Langguth H. Carvedilol stereopharmacokinetics in rats: affinities to blood constituents and tissues. Arch Pharm (Weinheim). 1993;326(9):529–33.

Issa ZF, Miller JM, Zipes DP. Chap 23, Idiopathic Focal Ventricular Tachycardia. In: Clinical arrhythmology and electrophysiology: a companion to Braunwald’s heart disease. 3rd edn. Philadelphia: Elsevier Science; 2019.

Lerman BB, Belardinelli L, West GA, Berne RM, DiMarco JP. Adenosine-sensitive ventricular tachycardia: evidence suggesting cyclic AMP-mediated triggered activity. Circulation. 1986;74(2):270–80.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This research was supported by a Grant from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (Grant No. HI17C2594).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JH and KL involved in writing draft and analyzing data. SH was involved in writing draft and creating concept of study. H-JB, S-WC, C-HL, I-CK, Y-KC, H-SP, H-JY, HK, C-WN, S-HH involved in data review and writing draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Availability of data and materials

No agreement on data release.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol of the current study was approved and waived for informed consent by the Keimyung University Dongsan Medical Center Institutional Review Board (No. 2017-12-05) due to its retrospective nature.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hwang, J., Lee, K., Han, S. et al. Effect of carvedilol on premature ventricular complexes originating from the ventricular outflow tract. Int J Arrhythm 21, 7 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42444-020-00015-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42444-020-00015-7