Abstract

Background

Wildfires, like many disturbances, can be catalysts for ecosystem change. Given projected climate change, tree regeneration declines and ecosystem shifts following severe wildfires are predicted. We reviewed scientific literature on post-fire tree regeneration to understand where and why no or few trees established. We wished to distinguish sites that won’t regenerate to trees because of changing climate from sites where trees could grow post fire if they had a seed source or were planted, thus supporting forest ecosystem services for society and nature, such as timber supply, habitat, watershed protection, and carbon storage.

Results

Our literature review showed that little to no post-fire tree regeneration was more common in low-elevation, dry forest types than in high-elevation forest types. However, depending on the region and species, low tree regeneration was also observed in high elevation, moist forests. Regeneration densities varied by species and seedling densities were attributed to distances to a seed source, water stress or precipitation, elevation, slope, aspect, and plant competition. Our findings provide land managers with two primary considerations to offset low tree regeneration densities. First, we supply a decision support tool of where to plant tree seedling in large high severity burned patches. Second, we recommend possibilities for mitigating and limiting large high severity burned patches to increase survival of trees to be sources of seed for natural regeneration.

Conclusions

Few or no tree seedlings are establishing on some areas of the 150+ forest fires sampled across western US, suggesting that forests may be replaced by shrublands and grasslands, especially where few seed source trees survived the wildfires. Key information gaps on how species will respond to continued climate change, repeated disturbances, and other site factors following wildfires currently limit our ability to determine future trends in forest regeneration. We provide a decision tree to assist managers in prioritizing post-fire reforestation. We emphasize prioritizing the interior of large burned patches and considering current and future climate in deciding what, when, and where to plant trees. Finally, managing fires and forests for more seed-source tree survival will reduce large, non-forested areas following wildfires where post-fire management may be necessary.

Resumen

Antecedentes

Los incendios, como muchos disturbios, pueden ser catalizadores para cambios en el ecosistema. Dadas las proyecciones del cambio climático, se predice una declinación en la regeneración de árboles y cambios en el ecosistema después de incendios severos. Revisamos la literatura científica para entender dónde y por qué pocos o ningún árbol se establece en la regeneración post-fuego. Deseábamos distinguir sitios que no regeneraban en árboles debido al cambio climático de aquellos sitios en que los árboles podrían crecer si tenían una fuente de semillas o fueran plantados en el post-fuego, sustentando la idea de proveer servicios ecosistémicos del bosque para la sociedad y la naturaleza, como productos forestales, hábitat, protección de cuencas, y almacenamiento de carbono.

Resultados

Nuestra revisión bibliográfica muestra que la escasa o nula regeneración arbórea post-fuego fue más común en tipos de bosques secos ubicados a bajas alturas que en bosques ubicados a mayores elevaciones. Sin embargo, dependiendo de la región y de la especie, una baja regeneración de árboles fue observada en lugares húmedos y a altas elevaciones. La densidad de la regeneración varió de acuerdo a la especie, y la densidad de plantines fue atribuida a la distancia de la fuente de semillas, el estrés hídrico o precipitación, la elevación, la pendiente, la exposición, y la competencia con otras plantas. Nuestros resultados proveen a los gestores de tierras con dos consideraciones primarias para compensar la baja densidad en la regeneración. Primero, presentamos una herramienta de ayuda sobre dónde plantar plantines en grandes parches quemados con alta severidad. Segundo, recomendamos la posibilidad de mitigar y limitar los parches de alta severidad para incrementar la supervivencia de árboles para que sirvan de fuentes de semilla para su regeneración natural.

Conclusiones

Pocos o ningún plantín se establecen en algunas en las de las áreas de los más de 150 bosques muestreados a través del oeste de los EEUU, sugiriendo que esos bosques pueden ser reemplazados por arbustales y pastizales, especialmente donde pocos árboles que actúan como fuentes de semillas sobreviven a los incendios. Existen vacíos de información que son clave para entender cómo las especies responderán a la continuidad del cambio climático, la repetición de disturbios y otros factores de sitio subsecuentes a los incendios y que limitan actualmente nuestra habilidad para determinar tendencias futuras en la regeneración de bosques. Proveemos de un árbol de decisiones para asistir a los gestores a priorizar la reforestación post-fuego. Enfatizamos la priorización de los grandes parches en el interior de grandes incendios y la consideración del cambio climático actual y futuro en la decisión de qué, cuándo y dónde plantar árboles. Finalmente, el manejo del fuego y los bosques para lograr que más árboles semilleros sobrevivan a los incendios va a reducir las grandes áreas que quedan sin árboles en el post-fuego, en las cuales el manejo post-fuego puede ser necesario.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Continuing climate change, droughts, and extreme weather (IPCC 2013), coupled with associated changes in wildfire activity (Westerling et al. 2006, Westerling et al. 2011, Abatzoglou and Williams 2016) are resulting in landscape ecosystem changes and shifts in community composition (Stevens-Rumann et al. 2018). Climate change is altering the mountainous ecosystems of the western US and affecting the people who depend on them for ecosystem services and livelihoods. With rapid biophysical changes already occurring in these forests, land managers are increasingly seeking to understand and mitigate the effects of a changing climate. Effective action depends on understanding regional and local implications of climate science and ecological effects (Blades et al. 2016), which can directly affect fire extent, tree mortality, and post-fire ecosystem recovery.

Legacies of prior disturbances and land use history, in addition to climate, play a prominent role in disturbance severity and subsequent recovery following disturbances (Hessburg et al. 2005, Westerling et al. 2011). While ecosystem shifts are concerning in any ecosystem type, the transition from forests to grasslands and shrublands is often particularly alarming due to the loss of carbon storage capacity in forests versus grasslands or shrublands (Liang et al. 2018), habitat loss for many wildlife species (e.g., Hobson and Schieck 1999), and the potential economic loss in timber industries (Thomas et al. 2017). In some settings, shifts to grassland or shrubland may be long-persisting as alternate stable states that do not transition back to forested ecosystems (e.g., Savage and Mast 2005). Although some studies forecast a reduction of conifer-dominated ecosystems in the coming century due to a combination of climate and disturbances, these studies also point to locations where conifer regeneration may be abundant (Baker 2018, Serra-Diaz et al. 2018).

Forest ecosystem transitions are precipitated by both mortality of mature trees and reduced recruitment. Extensive mortality of mature trees due to wildfires, bark beetles, and drought is of growing concern. Severe wildfires contribute to millions of hectares of mature forest loss in the western US every year (NIFC 2018). While there is some debate about whether the proportion of area burned at high severity within large wildfires has increased in recent years (Dillon et al. 2011; Flannigan et al. 2013, van Mantgem et al. 2013, Parks et al. 2016a), area burned in large wildfires has increased over the past 30 years in the western US (Dennison et al. 2014). Further, mature tree mortality induced by drought stress and the compounding susceptibility to insects has contributed to reduction of forest cover worldwide (Allen et al. 2010, Hicke et al. 2012, Anderegg et al. 2015).

Conifer tree species in the western US exhibit many different life history strategies. Some have traits that aid in regeneration after high-severity fire, including bradspory, or serotiny, in which cones only open after heat is applied, thus protecting seed during a high-intensity fire and releasing viable seeds immediately following wildfires (Lotan 1967). Species like lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta Douglas ex Loudon) are often identified as serotinous; however, the proportion of serotinous cones and individuals is highly variable and largely unknown outside of the greater Yellowstone area (Lotan 1967). Populations of lodgepole pine outside of the Rocky Mountains may be primarily non-serotinous, depending on site and disturbance history (Lotan 1967, Alexander 1974). Most conifers in western North America rely on other seed dispersal and reproduction mechanisms. For example, species like whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis Engelm.) and limber pine (Pinus flexilus James) can rely on dispersal by animals (Agee 1993). Many other species, including ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa Lawson & C. Lawson) and Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii [Mirb.] Franco), rely on nearby seed trees for wind or gravity dispersal (Agee 1993). Surviving trees are critical sources of seed for tree replacement after fires, thus the severity and extent of mature tree mortality is critical, although less so for serotinous trees. For many species, living seed trees and the number and viability of their seeds plays a critical role in tree establishment. Drought and temperature stress impact the youngest life stages of many plants (Bell et al. 2014, Dobrowski et al. 2015, Petrie et al. 2016). Thus, even with available seed, germination and establishment may be controlled by climatic conditions (Petrie et al. 2016), and temperature and moisture requirements vary significantly by species (Petrie et al. 2016, Davis et al. 2018). In many ecosystems, site conditions such as aspect, slope, and microsite conditions can influence success, with fewer tree seedlings often found on harsh sites (e.g., Bonnet et al. 2005). However, it is unclear how seed source, climate, competition or facilitation, and micro-climates may interact to either promote or inhibit successful reestablishment post fire.

Managers commonly plant trees or plan for natural regeneration from local seed sources (Johnson et al. 2010). On federal and state lands in the US, policies require reforesting after logging and fires within areas that are actively managed for timber supply (e.g., 16 U.S.C. § 475, 16 U.S.C. § 551; 81 FR 24785). On private lands, reforestation is typically required after a disturbance by state forest practices acts (e.g., Idaho IDAPA 20.02.01, Washington Title 222 WAC). While some planting may be contested from a historical fire regime perspective or when regeneration is expected to be slow and episodic (e.g., Owen et al. 2017, Baker 2018), managers of many public and private lands are mandated to regenerate by law and policy. Thus, there is a need to strategically target their limited money, personnel, and time where they will be effective.

In a regional study of the Rocky Mountains of the US, Stevens-Rumann et al. (2018) found decreases in tree regeneration in recent decades partly as a result of increasing temperatures and low moisture availability and long distances to seed sources. They detected a significant change in post-fire climate for fires that burned after 2000 in comparison to fires that burned between 1984 and 2000. However, Stevens-Rumann et al. (2018) did not cover a full range of forest types across their study areas, with only subalpine and upper montane forests represented in the northern Rockies, and this warranted an additional analysis of the literature. Here, we built upon this regional dataset with a literature review to address the following questions for all western US forests:

-

1)

To what extent do recent studies of post-fire tree regeneration indicate patterns of low tree regeneration densities post fire?

-

2)

What causes are attributed to low tree regeneration densities post fire?

-

3)

What are the ecological and management implications for the future throughout the West, particularly where extensive mature tree mortality due to fire is coupled with low regeneration densities?

We conducted a systematic review of recently published literature that reported field data on natural tree regeneration following wildfires in the western US. We discuss the ecological and management implications for the future, particularly when a lack of regeneration is coupled with extensive mature tree mortality. We outline key information gaps and scientific uncertainties that currently limit our ability to determine trends in forest regeneration and predict locations of future climate-induced ecosystem transitions. Finally, we discuss possible management actions that may offset the effects of low regeneration densities, and on which sites.

Methods

We conducted a systematic search for published accounts of post-fire tree regeneration using the ISI Web of Science (https://login.webofknowledge.com) and Google Scholar (https://scholar.google.com/). We used different three-word combinations of these key words: “wildfire” and “forest” or “tree regeneration,” or “seedling” and “failure” or “lack of” or “alternate stable states” or “transition” in the searches on both ISI Web of Science and Google Scholar. In addition, we used Google Scholar to find more recent publications that had cited the publications found in our search. To identify potential explanatory factors for tree seedling density, we additionally searched for terms “distance to seed source,” or “climate,” or “repeated fire” in conjunction with “wildfire.” Only peer-reviewed papers published since 2000 that included field measurements of natural (not planted) post-fire tree seedling density in the western US were included in our analysis. Many researchers included statistical modeling, and a few had manipulative experiments or simulation modeling, but such papers without field observations were excluded because we wanted to understand observed tree regeneration patterns.

Data presented here are from studies that focused on natural regeneration. Additionally, we excluded post-fire studies that gave densities of seedlings but did not analyze factors potentially influencing the observed tree regeneration. We limited our inferences to only those studies or parts of studies that focused on areas not treated post fire. Forests worldwide are faced with similar concerns over low regeneration densities (e.g., Retana et al. 2002, Pausas et al. 2008, Paritsis et al. 2015, Morgan et al. 2018); however, we felt the potential influencing factors across the world would be many and thus were excluded from our review. While we focused primarily on conifer species, all tree species mentioned in each paper were considered. We focused on papers published since the year 2000 for several reasons. First, if regeneration densities are changing due to climate and increased area burned, as demonstrated in multiple studies (e.g., Littell et al. 2009), then we expected these effects to be evident in more recent literature. However, multiple wildfires included in studies presented here burned prior to 2000, with the earliest wildfires in the review dating from the 1940s. Second, while localized climate data dates back to 1979, the availability of these data and use in post-fire studies is only found in the literature in the last 5 to 10 years. While we included papers in the discussion that focused on >100-year-old fires that employed dendrochronological methods for tree establishment, we intended to focus on patterns of recent regeneration in our review. Additionally, there are many potential disturbances that interact with wildfires to change post-wildfire recovery, such as wind events, pathogens, seed predation, human disturbances, etc. While papers that discussed these topics were included, we focused on the other driving factors of regeneration for this review as well as on the two most prevalent repeated disturbances in the literature: repeated wildfires and bark beetle-fire interactions.

In our management recommendation, we excluded discussions of other post-fire and pre-fire management strategies besides wildfires and planting, as these other aspects of management were not addressed directly in this review. We did not incorporate any studies of regeneration after prescribed fire or forest treatments and did not synthesize data on salvage logging, mulching, or other post-fire management actions. Thus, we did not provide recommendations around these actions.

Results

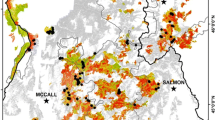

We found more than 200 publications in our search. After those not meeting our criteria were excluded, we included the remaining 49 in our synthesis. These publications documented tree seedling presence or density by species for 1 to 64 years following more than 150 wildfires in forests across the western US (Fig. 1).

Fires presented in all selected US studies listed in Additional file 1 that were reviewed as a part of this study. In many cases, a single study spanned a fairly large geographic range, thus the location of the author’s name and year are centrally located among multiple fires. Some wildfires were approximated either because a map of wildfires samples was not provided in the original publication or the names of the wildfires were missing

Post-fire regeneration from 20 conifer tree species were measured in these studies, the most common being ponderosa pine, lodgepole pine, Douglas-fir, subalpine fir (Abies lasiocarpa [Hook.] Nutt.), and Englemann spruce (Picea engelmanii Parry ex Engelm.). Other conifers found in at least one study were twoneedle pinyon (Pinus edulis Engelm.), knobcone pine (Pinus attenuata Lemmon), sugar pine (Pinus lambertiana Douglas), Jeffery pine (Pinus jeffreyi Balf.), whitebark pine, limber pine, bristlecone pine (Pinus aristata Englem.), grand fir (Abies grandis [Douglas ex D. Don] Lindl.), white fir (Abies concolor [Gord. & Glend.] Lindl. ex Hildebr.), red fir (Abies magnifica A. Murray bis), western larch (Larix occidentalis Nutt.), incense-cedar (Calocedrus decurrens [Torr.] Florin), Rocky Mountain juniper (Juniperus scopulorum Sarg.), alligator juniper (Juniperus deppeana Steud.), and oneseed juniper (Juniperus monosperma [Engelm.] Sarg.). In addition, non-coniferous species that generally composed a small proportion of the observed regeneration except in certain locations included quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides Michx.), Gambel oak (Quercus gambelii Nutt.), Emory oak (Quercus emoryi Torr.), California black oak (Quercus kelloggii Newberry), canyon live oak (Quercus chrysolepis Liebm.), Pacific madrone (Arbutus menziesii Pursh), tanoak (Notholithocarpus densiflorus [Hook. & Arn.] P.S. Manos, C.H. Cannon, & S.H. Oh), and bigleaf maple (Acer macrophyllum Pursh).

Tree seedling density was highly variable, with some plots within a given fire having an abundance of seedlings and other sites having few to none. The warmest and driest sites near lower timberline had the highest probability of none or very few seedlings. Researchers attributed the lack of post-fire tree regeneration success to multiple factors, including distance to seed source, burn severity, moisture stress, increased temperatures, repeated disturbances, topographic variables, and competing vegetation.

Areas with high mortality of mature trees had few tree seedlings. In the studies assessed here, seed availability was often inferred from either distance to a living tree seed source or burn severity. In 26 studies, researchers measured and provided statistical significance for distance from plots or transects to living trees, although whether this was to a single living tree or distance to a low-severity burned or unburned patch with many trees varied among the studies (Table 1). In 24 of the 26 studies, tree regeneration density decreased significantly at distances of 40 to 400 meters from a living mature tree, regardless of which conifer species was dominant.

Multiple researchers analyzed tree seedling density by burn-severity class (low, moderate, and high severity) or some other ground-truthed version of severity (Table 2). For example, Coop and Schoettle (2009) used “partial burn” or less than 100% versus “complete burn” or 100% tree mortality, while Welch et al. (2016) used five severity classes. Additionally, multiple studies measured both severity and distance to seed source (e.g., Coop et al. 2010, Rother and Veblen 2016). Proximity to potential seed source trees is often assessed using burn-severity classes, and these burn-severity categories and distance to seed source can be highly correlated (Kemp et al. 2016). In several studies, tree regeneration was not significantly correlated with burn severity, but tree regeneration did vary with distance to seed source (Coop and Schoettle 2009; Rother and Veblen 2016). Most studies examined here found either no relationship between regeneration and burn severity or a significant decline in regeneration at high-severity burned sites. In contrast, Coop et al. (2010) and Shive et al. (2013) found the highest tree regeneration densities at high-severity burned plots, although distance to a living tree was still important.

Numerous additional studies stated that distance to a living tree was measured but did not report if this metric was significant in predicting regeneration. For example, Ouzts et al. (2015) recorded distance to the nearest seed source up to 36 m away but no farther, and Harvey et al. (2013) included distance to seed source in a regression tree, but neither study reported these results. Donato et al. (2009) stated the range of distance to seed sources measured, but did not present analysis on this variable. Similarly, Savage and Mast (2005), Shive et al. (2013), and Morgan et al. (2014) stated that patterns of tree regeneration were influenced by distance to seed source, but results of analysis on this factor were not presented.

Only six studies explicitly analyzed climate as a factor in post-fire tree regeneration. The significant climate metrics included moisture deficit of some kind as the most common influence on regeneration, followed by either annual or seasonal precipitation (Table 3). While all studies identified here found that water stress influenced regeneration, one study demonstrated a relationship to degree days for one species (Urza and Sibold 2017). Donato et al. (2016), Kemp et al. (2016), and Dodson and Root (2013) discussed potential site climates through topographic proxies and metrics like heat load index, forest type, or elevation-precipitation-temperature gradients, but did not analyze climate directly.

Repeated disturbances, topography, and competing vegetation also influenced tree regeneration. In the five studies that examined tree seedling response to repeated wildfires, short intervals between wildfires (1 to 30 years) resulted in a decline in post-fire tree regeneration density compared to once-burned areas (Table 4). The four studies on the effect of bark beetle outbreaks and wildfires were less consistent across species and studies. Topographic factors including elevation, aspect, and slope, were common predictors in many of the studies assessed here, as were potential competition of shrubs, non-native grasses, and resprouting deciduous trees. At least 27 studies presented in this review found one of these factors to be significant (Additional file 1).

Discussion

Fires are catalysts for forest change

Several factors dominated in explaining tree regeneration patterns post fire. First, seed supply is required for seedling establishment unless planted; thus, proximity to living trees was important across many of the tree species in the studies presented here, including species that are serotinous, animal dispersed, and wind or gravity dispersed. Tree regeneration density decreased at distances of 40 to 400 meters from a living mature tree, especially for ponderosa pine, Douglas-fir, and true firs across the western US. However, several studies of often animal-dispersed species such as whitebark pine and limber pine also experienced a decline in density at longer distances from seed trees. Both Coop and Schoettle (2009) and Leirfallom et al. (2015) found tree seedling densities declined with increasing distance from mature trees unaffected by white pine blister rust (Cronartium ribicola J.C. Fisch), although this decline was more gradual than for species that only relied on wind or gravity dispersal. Studies that examined the relationship between lodgepole pine seedling density and distance to a living lodgepole pine found variable relationships. For example, Turner et al. (2004) found a small but significant negative relationship of seedling density to distance to live seed source, while Kemp et al. (2016) and Urza and Sibold (2017) and Turner et al. (2016) found no relationship. Donato et al. (2016) found a positive relationship between distance to live seed source and relative abundance of lodgepole pine seedlings. However, this could be explained by the proximity to nearby burned, serotinous individuals and lack of other species regenerating at far distances from living trees, rather than a relationship to live lodgepole pine trees. To some degree, the lack of consistency in the importance of proximity of a burned location to live lodgepole pines may be due to the proportion of lodgepole pines that are serotinous, which was demonstrated through the differing predictive factors of serotinous versus non-serotinous lodgepole pine by Harvey et al. (2016). In this case, non-serotinous lodgepole pine was negatively correlated to distance while serotinous lodgepole pine was not (Harvey et al. 2016). Additionally, the distance at which regeneration declined appeared to vary by species, with seedling density declining at distances around 400 m from seed-source Douglas-fir trees in the Pacific Northwest (Donato et al. 2009), and as close as 40 to 100 m from seed-source ponderosa pines in the Black Hills in South Dakota, the southern Rocky Mountains in Colorado and Wyoming, and the Pacific Southwest (e.g., Bonnet et al. 2005, Ritchie and Knapp 2014, Rother and Veblen 2016). To some degree, regional differences may be driven by different regenerating species, like patterns of regeneration in ponderosa pine versus Douglas-fir. However, many studies reported significance of regeneration across all species, not for individual species except for Kemp et al. (2016), Urza and Sibold (2017), Coop and Schoettle (2009), and Harvey et al. (2016) (See Additional file 1 for more details). Additionally, several studies only saw one regenerating species; thus, their findings were specific to only one species, such as Bonnet et al. (2005) in the Black Hills, which only observed ponderosa pine regeneration.

A burned site’s distance to living trees to living trees is also simply a proxy for explaining the availability of seeds. However, the assumption that living nearby trees equals adequate available seed is not always accurate. For example, Leirfallom et al. (2015) demonstrated that it was the proximity to healthy, non-blister-rust affected, whitebark pine trees that was important, not just proximity to simply living trees. Similarly, ponderosa pine trees in the southwestern US and in the southern Rocky Mountains have episodic regeneration events (Savage et al. 1996). Thus, proximity to a living, mature tree does not always guarantee seed availability. More research is needed to identify locations where the lack of tree regeneration is due to lack of seed production or seed viability instead of proximity to trees.

Second, changing climatic conditions are influencing regeneration densities, as climate has for centuries. With the increasingly warm springs and summers in recent decades throughout the western US (IPCC 2013), conditions for seedling survival are changing. On the driest sites, even a small increase in water deficit could negatively influence tree regeneration (Stevens-Rumann et al. 2018). On colder, more mesic sites, these changing climatic conditions could promote regeneration where previously limited by cold or snow (Stevens-Rumann et al. 2018). Water deficit, low precipitation, or drought reduced regeneration success in all studies. The correlation between increased regeneration and available moisture is supported by Petrie et al. (2017), who found this to be an important predictor of seedling success in greenhouse experiments. Additionally, in a multi-century analysis of tree establishment, Brown and Wu (2005) found strong links between seedling establishment and moister climatic conditions. However, in the case of Brown and Wu (2005), the pattern of establishment during cooler and wetter climatic periods correlated with periods of decreased fire activity; thus, the growth of individual trees to a fire-resistant age between wildfires may contribute to the observed cohort of tree establishment, as others have found (Meunier et al. 2014). Modeling exercises similarly found correlations between tree seedling response and both moisture gradients and temperature following wildfires (Hansen et al. 2018). Thus, changes in precipitation patterns may play a large role in the vulnerability of regenerating trees in a warmer climate, and abnormally moist years following wildfires may allow for germination and establishment in otherwise non-regenerating sites. The relationship between climate and regeneration is an aspect of post-fire seedling establishment that warrants extensive additional research.

Individual tree species respond differently to environmental stressors due to their varying environmental requirements and species characteristics (Dobrowski et al. 2015, Davis et al. 2019). In dry forests dominated by ponderosa pine and Douglas-fir trees, ponderosa pine appears to be more susceptible to regeneration failure (Davis et al. 2018), but current observed patterns could also be related to the longer seed dispersal distances for Douglas-fir. However, these studies focus on lower elevational ranges of these species; thus, it is important to consider how species ranges may expand as higher elevations and higher latitudes become more favorable to tree growth (Lenoir et al. 2008). In this review, only three studies explicitly tested for species shifts following wildfires (Buma and Wessman 2011, Kulakowski et al. 2013, Donato et al. 2016), and only one examined potential climate-induced range shifts following wildfires (Donato et al. 2016). Understanding how species ranges may expand, in addition to contract, will be critically important for forest management of burned areas in the coming decades.

As discussed previously, most studies presented here combined species for analyses even though it is well understood that species respond differently to environmental and climatic conditions. This is further demonstrated by climate envelope modeling (e.g., Rehfeldt et al. 2014), which suggests that different species will have variable responses to climate change. Rehfeldt et al. (2014) predicted a 50% decline in the range of ponderosa pine by 2060. Alternatively, in higher elevation forests, most observed tree regeneration studies demonstrated consistent and often abundant regeneration of lodgepole pine, even where there were few seedlings of other tree species (e.g., Harvey et al. 2016). While documented declines in lodgepole pine regeneration have not been observed, there is modeling evidence that lodgepole pine may see substantial declines in the coming decades due to both an increase in fire frequency (Westerling et al. 2011) and continued changes in climatic conditions (Coops and Waring 2011). All of this speaks to the large degree of uncertainty around individual species responses to climate variability following wildfires.

Third, multiple disturbances such as bark beetles and fire and repeated fire are playing an increasingly important role in tree establishment. As the extent of wildfires increases, in part due to climate (Westerling et al. 2011; Dennison et al. 2014), so will the area repeatedly burned (Prichard et al. 2017). Similarly, interactions between wildfires, drought, insects, and pathogens are expected to increase (Hicke et al. 2016). Repeated wildfires or the combination of bark beetle infestation and wildfire may influence ecosystem transitions. Repeated high-severity wildfires in short succession may be precipitating vegetation changes (Table 4). This change is likely due to the repeated disturbances themselves, not increasing distance to seed source, as at least in several studies, distance to seed source did not vary between once burned and repeatedly disturbed areas (e.g., Stevens-Rumann and Morgan 2016). However, repeated wildfires at low to moderate severity that result in the survival of at least some overstory trees, especially in low elevation forests that would have historically burned at more frequent intervals, may be maintaining more open forests rather than precipitating a transition to non-forested ecosystems (Larson et al. 2013; Stevens-Rumann and Morgan 2016, Walker et al. 2018). In studies of tree seedling response after bark beetle outbreaks and wildfires, the findings are less consistent and these two disturbances, in many cases, do not seem to be decreasing tree regeneration (Harvey et al. 2014a, 2014b ; Stevens-Rumann et al. 2015). Conversely, Harvey et al. (2013) did find significant declines in tree regeneration follow bark beetle outbreaks and high-severity wildfires in Douglas-fir-dominated systems. Given the relatively small number of studies on repeated disturbances and lack of agreement among studies, future research is needed, especially in the face of increasingly common overlap of disturbances in both time and space.

Fourth, tree regeneration was less successful post fire in particular site conditions, with the most common influences being elevation, slope, aspect, and competing vegetation. Steeper slopes and more westerly or southerly aspects often resulted in lower regeneration density compared to shallower slopes and northerly and easterly aspects (Lydersen and North 2012, Kemp et al. 2016; Ziegler et al. 2017). In some locations, highly competitive and potentially flammable non-forest vegetation may result in positive feedbacks by burning readily and thus continuing dominance by non-forest vegetation (Wilson and Agnew 1992, Donato et al. 2009). In many locations, forests are being replaced by non-forest vegetation, but the replacing vegetation varies. In California, the primary concern, especially in drier forest sites at low elevations, is that the chaparral shrubland vegetation replacing forests is highly flammable (e.g., Collins and Roller 2013). In the US northern Rocky Mountains, forests are more commonly replaced by grass or shrubs (e.g., Kemp et al. 2016), while in the southwestern US and some places in the southern Rocky Mountains, conifers are often being replaced by resprouting trees or shrubs (e.g., Haire and McGarigal 2010, Roccaforte et al. 2012). All these potential ecosystem transitions to grasslands or shrublands should be assessed with an understanding of the historical heterogeneity. In some places, wildfires may be restoring the historical vegetation structure where tree establishment only occurred as a result of fire suppression (Hessburg et al. 2005, Nagel and Taylor 2005). Thus, there is a need to identify where the lack of regeneration is creating new and novel conditions on a site versus where little or no regeneration is promoting historical heterogeneity. More research is needed in this area to promote sound management intervention in areas of concern.

Understanding the relative importance of the variables presented here will be critical for adaptive fire management in the future. Climate may drive changes in some forested systems, while the disturbance, topography, or competing vegetation may drive changes in other forests. Scientists and managers are implementing experiments to understand the contributing factors (e.g., Tercero-Bucardo et al. 2007, Rother et al. 2015, Petrie et al. 2017), but more analysis of species-specific vulnerabilities is needed to fully understand responses to climate, landscape settings, and biological interactions.

Limitations and research needs

Comprehensive understanding of the drivers of natural regeneration and thus areas where true regeneration “failures” occur is limited by three prominent limitations that warrant further research: (1) understanding spatial variability across burned landscapes, (2) quantifying temporal variability of regeneration patterns, and (3) identifying the controlling mechanisms of regeneration success. First, while tree seedling density may be low in many burned areas, it is highly variable spatially and, as such, researchers should be careful to conclude that large, high-severity burned patches are not regenerating at all without sampling larger plots to characterize spatial variability of fire effects and tree regeneration. The plots used to sample tree regeneration were small across most studies (generally less than 600 m2). However, in studies using plot sizes of 4 ha, tree seedlings were always detected (Owen et al. 2017). Fully understanding spatial and temporal variability of fire effects and vegetation post fire is important to ecosystem function, yet we often do not capture this with a smaller plot size and short periods of study.

Second, time since fire has long been a concern for making inferences about ecosystem trajectory and recovery. Some long-term studies suggested continued recruitment through decades to even centuries following wildfires (MacKenzie et al. 2004, Tepley et al. 2013, Freund et al. 2014). While many of the sites studied here may continue to see tree regeneration in the coming decades, short-term tree regeneration patterns are often highly correlated with long-term regeneration patterns (e.g., Coop et al. 2010). Thus, the patterns of regeneration in the first few years post fire will likely influence the trajectory of that ecosystem (Turner et al. 2016). Most of the studies only presented data for <10 years post fire, with some studies as short as 1-2 years post-fire (e.g., Strom and Fule 2007, Larson et al. 2013), although some studies presented did span a large time since fire, of 25-64 years post fire (e.g., Passovoy and Fule 2006, Haire and McGarigal 2010). Further, past regeneration patterns may be very different from future patterns given the increasingly unfavorable climate for tree regeneration, especially at lower elevational ranges. Thus, discussion of persistent non-forest vegetation shifts is more prevalent and the level of uncertainty around continued gradual regeneration through time is an ongoing concern. That said, some of these vegetation shifts may be offset by one or several consecutive moist or cool and moist years that could promote tree establishment and growth, even in a warmer climate (Serra-Diaz et al. 2018), thus there is need for additional research into the mechanisms controlling tree germination and regeneration.

Finally, the processes driving seedling establishment and survival in burned areas specifically may vary from unburned areas and greenhouse experiments (Petrie et al. 2017). The interaction among all potential influencing drivers in post-fire environments are complex, and measurements like distance of a site to living trees or fine resolution climate variables may not adequately explain the processes involved in germination and survival. Some alternative explanations for a lack of regeneration that were not considered here but could be important include competing vegetation, other pre-fire disturbances not often described (e.g., Buma and Wessman 2011, Leirfallom et al. 2015), highly variable cone production, seed viability that is linked to climate and many other factors (e.g., Buechling et al. 2016), and slow regeneration rates that may be natural for some species and harsh sites. Authors of studies presented here often attributed slow regeneration to changing climate, but there are relatively few studies on physiology of cones, seeds, and seedlings in these settings. To truly determine how a lack of regeneration in the short term post fire corresponds to long-term persistence of non-forest communities, further considerations of these mechanistic influences, temporal variability, and spatial variability are necessary.

Management in a world of more fires and less tree regeneration

Multiple management strategies can be employed to help forests adapt to more fires and more burned area in a changing climate. Specifically, we propose several management strategies to promote tree survival during fires and higher likelihood of tree regeneration success, especially of tree species that are not serotinous. We generally break these strategies into two categories that correspond to two of the dominant drivers of tree regeneration presented here: (1) how to adapt post-fire management strategies, such as planting, to changing climate, and (2) how to mitigate large high-severity burn patches and, thus, long distances to living tree seed sources.

Planting in a changing climate

Strategies for managing landscapes after wildfire must consider climate suitability now and in the future. The many factors interacting to influence seedling germination and establishment warrant consideration prior to post-fire management. We made a decision tree (Fig. 2) based on the literature presented here and in consultation with managers. This decision tree framework can be used to guide planting and other management considerations within wildfire perimeters. We propose that, along with considerations of the forest plans, site objectives, and funding availability, current and future precipitation quantity and patterns and temperature are carefully evaluated along with forest type that can indicate general climatic conditions. While science may suggest that climate consideration or forest type should be the first factor in decision making, we acknowledge that management of burned landscapes is often influenced by more than science; thus, our decision tree begins once an area has been prioritized for potential reforestation. In some cases, forest plans and general guidelines for site objectives should be refined to incorporate climate change more effectively, although this is beyond the scope of our decision tree.

Decision support tool for planting based on literature review of selected US studies from 2005 to 2018. Distances and slopes are approximate and based on mean values found in many studies, although exact values and locations should be altered by region and management unit and informed by local experience and monitoring. Aspect indicates the aspect that a hillside is facing: S-W indicates south- through west-facing slopes; N-E indicates north- through east-facing slopes. The triangle at the top indicates the gradient of forest types and climatic conditions that vary between the hottest and driest locations and the coolest and wettest, with increasing favorability as one moves to cooler and moister conditions. Dashed lines indicate a need to assess all locations for more localized important factors listed to the right after more broad scale assessments, prior to planting

As climate becomes increasingly unfavorable to tree establishment for many species within portions of their current distribution, we must identify areas that may be favorable for target species, given the current and future climate. As multiple studies presented here demonstrated, the climate on some sites may not be currently, or in the near future, compatible with the establishment and survival of those tree species present pre fire (e.g., Davis et al. 2019). Planting trees should be limited to prime locations for tree regeneration success, now and in the future climate, that are not expected to regenerate without management intervention. Thus, promoting productive and diverse non-forested ecosystems or new, novel forested ecosystems may be the best course of action in some locations. For example, many studies showed that those areas at the lowest elevations, or often in the hottest and driest forests were regenerating poorly (e.g., Dodson and Root 2013, Donato et al. 2016; Stevens-Rumann et al. 2018), thus it may be beneficial to identify whether these sites could continue to support similar species assemblages before planting, and perhaps prioritize those sites that are slightly cooler and wetter over the harshest sites. Alternatively, planting diverse tree species or a single species from a genetically diverse pool may help overcome some of the site productivity limitations, especially if current individuals are no longer suitable but a forest ecosystem is still desired.

Our second broad-scale, science-based consideration is proximity to a seed source. As the literature presented here demonstrated, there are multiple locations where tree regeneration is likely to be abundant, such as within small high-severity burned patches or within 50 to 100 m of living trees; thus, these areas may not need to be replanted. Conversely, planting may be necessary to reforest in large, high-severity burned patches with long distances to surviving seed-source trees. Distance to living trees was an important predictor of post-fire tree seedling density; thus, understanding the shape and size of high-severity burned patches is critical in understanding the potential for tree regeneration and when management intervention may be desired (Shive et al. 2018). Mapping high-severity burned patches through satellite imagery can begin to address which areas are large enough to warrant concern, and where competing vegetation may pose a threat to delayed planting success. In many cases, no planting may be recommended due to the size and shape of those large patches, even within large fires. Even in large patches, the irregular shape and unburned islands leave much burned area close to surviving trees that can be potential seed sources. For instance, Kemp et al. (2016) found that, on 21 large fires, >75% of the burned area was within 95 m of surviving trees. Thus, planting efforts should be focused on those largest, high-severity burned patches in which large areas within the patches are more than 100 to 400 m, depending on region and species, from a lesser burned edge or unburned island of substantive size (North et al. 2019).

We propose not planting trees close to the edge of high-severity burned patches to avoid areas that will likely experience high fuel accumulations through time (e.g., Roccaforte et al. 2012; Eskelson and Monleon 2018) and thus experience higher potential for reburning (Prichard et al. 2017). Prior fires can limit fire extent or burn severity for ~5 to 20 years, depending on region, forest type, and individual fire events (Parks et al. 2015; Parks et al. 2016b). Thus, providing a buffer and potential containment area within a high-severity burn perimeter will decrease the likelihood of burning planted seedlings. With the increasing likelihood of reburns, managers should be conscious of where and how subsequent fires may burn and how tree seedlings may contribute to the fuel loading. We propose planting only within the interior of large, high-severity burned patches to avoid loss of money and effort invested in planting tree seedlings.

After these first two broad-scale considerations of climate and seed source availability, we focus on those finer-scale topographic or topo-climate variables that are important for regeneration success across the western US. Elevation, aspect, and slope all play roles in identifying suitable locations for planting. We provide general guidelines for these different metrics, but local knowledge and adaptations will be necessary. For example, Kemp et al. (2016), Donato et al. (2016), and many others demonstrated that less regeneration was naturally occurring at the lowest elevation sites on south- to southwest-facing slopes, thus indicating that these sites may be outside of their climatic tolerance. Conversely, a south-facing slope at a high elevation location could promote regeneration at the upper elevational range of a particular species. Slope may be more important in combination with soil properties. Shallow soils on steep slopes may not promote regeneration establishment, but in deep, rich soils, perhaps the slope percentage is of less concern.

Finally, multiple studies found local site conditions to be important and should always be considered prior to planting. Identifying if and where competing vegetation may either deter natural regeneration or compete against planted seedlings may alter planting timelines. For instance, promoting immediate post-fire planting in areas of fast-growing, resprouting species may be more important in some areas, while in other areas where competing vegetation is less of a concern, allowing a couple of years to observe natural regeneration densities may be warranted before planting. Soil types and soil depths may influence the density or species planted, and a plethora of microsite conditions, such as the presence of nurse structures, may be important considerations (Haffey et al. 2018). All of these are very site specific and may even vary across a treatment unit, thus requiring manager discretion, drawing on local experience.

Using fire to promote natural regeneration

Hessburg et al. (2015) outlined seven principles for managing landscapes strategically. They emphasized the need for thinking about where to do what treatments, including doing nothing in some locations. Increasing landscape-level treatments, including thinning, fuels treatments, prescribed fire, or managed wildfires, could curtail the area that burns under extreme conditions, and thus increase the potential for survival of trees that could provide seed sources for regeneration. Currently, multiple researchers and managers are suggesting increasing strategic planning pre fire that focuses on limiting risk to firefighters, managing the very high costs of fire suppression, and developing a preemptive strategic plan for managing wildfires (Thompson and Calkin 2011, Schoennagel et al. 2017). Managing fires often includes aggressive fire suppression that will likely continue when human values are at risk. However, in places where risk to human values is low and ecological need is high, we join others in advocating for less aggressive suppression actions (Schoennagel et al. 2017, Halofsky et al. 2018). Likely, this means delaying, herding, and otherwise managing ongoing fires to foster survival of seed source trees and desirable patch size distribution (Hessburg et al. 2015). The National Cohesive Fire Management Strategy (USDA and USDI 2018), which is supported by federal, state, and other managers, calls for fire suppression when possible and desired, as well as using fire as part of natural resource management. Part of adapting to a future of more frequent and larger fires will be appreciating when wildfires are doing “good work” to further vegetation management goals.

With respect to post-fire tree regeneration, the broader goals of these managed wildfires include fostering survival of more adult trees to rain seed through time, and creating less severe, patchier fire effects. Both effects are more likely when fires burn under less extreme conditions—the very conditions in which fire suppression is most effective. Increasing the proportion of “fire refugia,” unburned or low-severity burned sites, could provide more ecological services (Kolden et al. 2012, Meddens et al. 2018), and while the promotion of fire refugia is important under any burning condition, less extreme weather conditions promote the creation and maintenance of “fire refugia” (Krawchuk et al. 2016). Some forest openings, especially when smaller in size, may be ecologically beneficial and increase the heterogeneity of landscapes.

Ultimately, these approaches blend together for, in most areas, fires will occur in the future and what we do post fire will affect the forest conditions prior to the next fire and how that next fire will burn. Decisions need to be strategic for, in years of widespread fire, there are more areas to plant than there are trees, and there are many sites that will likely not support similar forests to those found pre fire. All management strategies, including no action, have consequences that can be evaluated to inform management decisions.

Conclusions

Management actions that could offset the effects of low tree regeneration densities in the first years following a wildfire on some sites include prescribed burning and managing fires to burn more area under less extreme conditions to favor more seed source trees surviving, and planting post fire in locations where seedlings are most likely to survive in terms of microsite and site conditions and risk of future fires. Triage among sites is needed to strategically differentiate those sites for which management actions are most likely to be worth the effort and cost. For instance, post-fire tree seedling densities are high on many mesic sites, and on many sites close to seed source trees where regeneration may eventually occur, while others are so warm and dry that even with intensive effort, neither planted nor naturally regenerated trees are likely to survive (Stevens-Rumann et al. 2018). Baker (2018) aptly points out that some sites will regenerate slowly without intervention and management actions may not always be warranted. Fire suppression has, in many ecosystems across the western US, increased tree density, forest continuity, and homogeneity, and allowed encroachment of many trees into non-forested ecosystems (e.g., Gruell 2001, Nagel and Taylor 2005). As a result, some loss of forest area may restore historical landscape heterogeneity of different ecosystem types. Thus, while we have focused on the lack of tree regeneration and possible pathways for restoring forest ecosystems, in some cases promoting a non-forested ecosystem may be recommended even if the site is climatically suitable for forests.

While reactive treatments will no doubt occur, proactive management informed by assessment of forest vulnerability is sorely needed. Such an approach could mean that we prescribe more fires and manage more wildfires to foster future resilience (Schoennagel et al. 2017). However, with the projection for larger fires and longer fire seasons, vulnerability of forests for which disturbance-induced tree mortality overlaps with and contributes to lack of tree regeneration, we will also have to accept that some forests will be replaced by shrublands, woodlands, and grasslands as we adapt to a future with more fire.

References

Indicates studies used in literature review

Abatzoglou, J.T., and A.P. Williams. 2016. Impact of anthropogenic climate change on wildfire across western US forests. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113: 11770–11775. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1607171113

Agee, J.K. 1993. Fire ecology of Pacific Northwest forests. Island Press, Washington, D.C., USA.

Alexander, R.R. 1974. Silviculture of central and southern Rocky Mountain forests: a summary of the status of our knowledge by timber types. USDA Forest Service Research Paper RM-120, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA.

Allen, C.D., A.K. Macalady, H. Chenchouni, D. Bachelet, N. McDowell, M. Vennetier, T. Kitzberger, A. Rigling, D.D. Breshears, E.T. Hogg, P. Gonzalez, R. Fensham, Z. Zhang, J. Castro, N. Demidova, J.-H. Lim, G. Allard, S.W. Running, A. Semerci, and N. Cobb. 2010. A global overview of drought and heat-induced tree mortality reveals emerging climate change risks for forests. Forest Ecology and Management 259: 660–684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2009.09.001

Anderegg, W.R.L., J.A. Hicke, R.A. Fisher, C.D. Allen, J. Aukema, B. Bentz, S. Hood, J.W. Lichstein, A.K. Macalady, N. McDowell, and Y. Pan. 2015. Tree mortality from drought, insects, and their interactions in a changing climate. New Phytologist 208: 674–683. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.13477

Baker, W.L. 2018. Transitioning western US dry forests to limited committed warming with bet-hedging and natural disturbances. Ecosphere 9(6): e02288. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.2288

Bell, D.M., J.B. Bradford, and W.K. Lauenroth. 2014. Early indicators of change: divergent climate envelopes between tree life stages imply range shifts in the western United States. Global Ecology and Biogeography 23: 168–180. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12109

Blades, J.J., P.Z. Klos, K.B. Kemp, T.E. Hall, J.E. Force, P. Morgan, and W.T. Tinkham. 2016. Forest managers’ response to climate change science: evaluating the constructs of boundary objects and organizations. Forest Ecology and Management 360: 376–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2015.07.020

Bonnet, V.H., A.W. Schoettle, and W.D. Shepperd. 2005. Postfire environmental conditions influence the spatial pattern of regeneration for Pinus ponderosa. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 35: 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1139/x04-157

Brown, P., and R. Wu. 2005. Climate and disturbance forcing of episodic tree recruitment in a Southwestern ponderosa pine landscape. Ecology 86: 3030–3038. https://doi.org/10.1890/05-0034

Buechling, A., P.H. Martin, C.D. Canham, W.D. Shepperd, and M.A. Battaglia. 2016. Climate drivers of seed production in Picea engelmannii and response to warming temperatures in the southern Rocky Mountains. Journal of Ecology 104: 1051–1062. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.12572

Buma, B., and C.A. Wessman. 2011. Disturbance interactions can impact resilience mechanisms of forests. Ecosphere 2(5): art64. https://doi.org/10.1890/ES11-00038.1

Chambers, M.E., P.J. Fornwalt, S.L. Malone, and M.A. Battaglia. 2016. Patterns of conifer regeneration following high severity wildfires in ponderosa pine dominated forests of Colorado Front Range. Forest Ecology and Management 378: 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2016.07.001

Collins, B.M., and G.B. Roller. 2013. Early forest dynamics in stand-replacing fire patches in the northern Sierra Nevada, California, USA. Landscape Ecology 28: 1801–1813. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-013-9923-8

Coop, J.D., R.T. Massatti, and A.W. Schoettle. 2010. Subalpine vegetation pattern three decades after stand-replacing fire: effects of landscape context and topography on plant community composition, tree regeneration and diversity. Journal of Vegetation Science 21: 472–487. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1654-1103.2009.01154.x

Coop, J.D., S.A. Parks, S.R. McClernan, and L.M. Holsinger. 2016. Influences of prior wildfires on vegetation response to subsequent fire in a reburned Southwestern landscape. Ecological Applications 26: 346–354. https://doi.org/10.1890/15-0775

Coop, J.D., and A.W. Schoettle. 2009. Regeneration of Rocky Mountain bristlecone pine (Pinus aristata) and limber pine (Pinus flexilis) three decades after stand-replacing fires. Forest Ecology and Management 257: 893–903. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2008.10.034

Coops, N.C., and R.H. Waring. 2011. Estimating the vulnerability of fifteen tree species under changing climate in northwest North America. Ecological Modelling 222: 2119–2129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2011.03.033

Crotteau, J.S., J.M. Varner III, and M.W. Ritchie. 2013. Post-fire regeneration across a fire severity gradient in the southern Cascades. Forest Ecology and Management 287: 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2012.09.022

Davis, K.T., P.E. Higuera, and A. Sala. 2018. Anticipating fire-mediated impacts of climate change using a demographic framework. Functional Ecology 32(7): 1729–1745. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.13132

Davis, K.T., S.Z. Dobrowski, P.E. Higuera, Z.A. Holden, T.T. Veblen, M.T. Rother, S.A. Parks, A. Sala, and M.P. Maneta. 2019. Wildfires and climate change push low-elevation forests across a critical climate threshold for tree regeneration. PNAS 116(13):6193–6198.

Dennison, P.E., S.C. Brewer, J.D. Arnold, and M.A. Moritz. 2014. Large wildfire trends in the western United States, 1984–2011. Geophysical Research Letters 41(8): 2928–2933. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014GL059576

Dillon, G.K., Z.A. Holden, P. Morgan, M.A. Crimmins, E.K. Heyerdahl, and C.H. Luce. 2011. Both topography and climate affected forest and woodland burn severity in two regions of the western US, 1984 to 2006. Ecosphere 2(12): 130. https://doi.org/10.1890/ES11-00271.1

Dobrowski, S.Z., A.K. Swanson, J.T. Abatzoglou, Z.A. Holden, H.D. Safford, M.K. Schwartz, and D.G. Gavin. 2015. Forest structure and species traits mediate projected recruitment declines in western US tree species: tree recruitment patterns in the western US. Global Ecology and Biogeography 24: 917–927. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12302

Dodson, E.K., and H.T. Root. 2013. Conifer regeneration following stand-replacing wildfire varies along an elevation gradient in a ponderosa pine forest, Oregon, USA. Forest Ecology and Management 302: 163–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2013.03.050

Donato, D.C., J.B. Fontaine, W.D. Robinson, J.B. Kauffman, and B.E. Law. 2009. Vegetation response to a short interval between high-severity wildfires in a mixed-evergreen forest. Journal of Ecology 97: 142–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2745.2008.01456.x

Donato, D.C., B.J. Harvey, and M.G. Turner. 2016. Regeneration of montane forests 24 years after the 1988 Yellowstone fires: a fire-catalyzed shift in lower treelines? Ecosphere 7(8): e01410. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.1410

Eskelson, B.N.I., and V.J. Monleon. 2018. A 6 year longitudinal study of post-fire woody carbon dynamics in California’s forests. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 46: 610–620. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjfr-2015-0375

Flannigan, M., A.S. Cantin, W.J. de Groot, M. Wotton, A. Newberry, and L.M. Gowman. 2013. Global wildland fire season severity in the 21st century. Forest Ecology and Management 294: 54–61.

Freund, J.A., J.F. Franklin, A.J. Larson, and J.A. Lutz. 2014. Multi-decadal establishment for single-cohort Douglas-fir forests. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 44: 1068–1078. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjfr-2013-0533

Gruell, G.E. 2001. Fire in Sierra Nevada forests: a photographic interpretation of ecological change since 1849. Mountain Press Publishing Company, Missoula, Montana, USA.

*Haffey, C., T.D. Sisk, C.D. Allen, A.E. Thode, and E.Q. Margolis. 2018. Limits to ponderosa pine regeneration following large high severity forest fires in the United States Southwest. Ecology 14: 143–162.

Haire, S.L., and K. McGarigal. 2010. Effects of landscape patterns of fire severity on regenerating ponderosa pine forests (Pinus ponderosa) in New Mexico and Arizona, USA. Landscape Ecology 25: 1055–1069. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-010-9480-3

Halofsky, J.S., D.C. Dontao, J.F. Franklin, J.E. Halofsky, D.L. Peterson, and B.J. Harvey. 2018. The nature of the beast: examining climate adaptation options in forests with stand-replacing fire regimes. Ecosphere 9(3): e02140. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.2140

Hansen, W.D., K.H. Braziunas, W. Rammer, R. Seidl, and M.G. Turner. 2018. It takes a few to tango: changing climate and fire regimes can cause regeneration failure of two subalpine conifers. Ecology 99: 966–977. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.2181

Harvey, B.J., D.C. Donato, W.H. Romme, and M.G. Turner. 2013. Influence of recent bark beetle outbreak on fire severity and postfire tree regeneration in montane Douglas-fir forests. Ecology 94: 2475–2486. https://doi.org/10.1890/13-0188.1

*Harvey, B.J., D.C. Donato, W.H. Romme, and M.G. Turner. 2014a. Fire severity and tree regeneration following bark beetle outbreaks: the role of outbreak stage and burning conditions. Ecological Applictions 24: 1608–1625. https://doi.org/10.1890/13-1851.1

Harvey, B.J., D.C. Donato, and M.G. Turner. 2014b. Recent mountain pine beetle outbreaks, wildfire severity, and postfire tree regeneration in the US northern Rockies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111: 15120–15125. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1411346111

Harvey, B.J., D.C. Donato, and M.G. Turner. 2016. High and dry: postfire tree seedling establishment in subalpine forests decreases with post-fire drought and large stand-replacing burn patches. Global Ecology and Biogeography 25: 655–669. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12443

Hessburg, P.F., J.K. Agee, and J.F. Franklin. 2005. Dry forests and wildland fires of the inland Northwest USA: contrasting the landscape ecology of the pre-settlement and modern eras. Forest Ecolology and Management 211: 117–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2005.02.016

Hessburg, P.F., D.J. Churchill, A.J. Larson, R.D. Haugo, C. Miller, T.A. Spies, M.P. North, N.A. Povak, R.T. Belote, P.H. Singleton, W.L. Gaines, R.E. Keane, G.H. Aplet, S.L. Stephens, and P. Morgan. 2015. Restoring fire-prone Inland Pacific landscapes: seven core principles. Landscape Ecology 30(10): 1805–1835. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-015-0218-0

Hicke, J., A.J.H. Meddens, and C. Kolden. 2016. Recent tree mortality in the western United States from bark beetles and forest fires. Forest Science 62: 141–153. https://doi.org/10.5849/forsci.15-086

Hicke, J.A., C.D. Allen, A.R. Desai, M.C. Dietze, R.J. Hall, D.M. Kashian, D. Moore, K.F. Raffa, R.N. Sturrock, and J. Vogelmann. 2012. Effects of biotic disturbances on forest carbon cycling in the United States and Canada. Global Change Biology 18: 7–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02543.x

Hobson, K.A., and J. Schieck. 1999. Changes in bird communities in boreal mixedwood forest: harvest and wildfire effects over 30 years. Ecological Applications 9: 849–863. https://doi.org/10.1890/1051-0761%281999%29009%5B0849:CIBCIB%5D2.0.CO;2

IPCC [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change]. 2013. Climate change 2013: the physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the fifth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Pages 1-1535 in: T.F. Stocker, D. Qin, G.-K. Plattner, M. Tignor, S.K. Allen, J. Boschung, A. Nauels, Y. Xia, V. Bex, and P.M. Midgley, editors. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England, United Kingdom, and New York, New York, USA.

Johnson, R., L. Stritch, P. Olwell, S. Lambert, M.E. Horning, and R. Cronn. 2010. What are the best seed sources for ecosystem restoration on BLM and USFS lands? Native Plants Journal 11: 117–131. https://doi.org/10.2979/NPJ.2010.11.2.117

Kemp, K.B., P.E. Higuera, and P. Morgan. 2016. Fire legacies impact conifer regeneration across environmental gradients in the US northern Rockies. Landscape Ecology 31: 619–636. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-015-0268-3

Keyser, T.L., L.B. Lentile, F.W. Smith, and W.D. Shepperd. 2008. Changes in forest structure after a large, mixed-severity wildfire in ponderosa pine forests of the Black Hills, South Dakota, USA. Forest Science 54: 328–338.

Kolden, C.A., J.A. Lutz, C.H. Key, J.T. Kane, and J.W. van Wagtendonk. 2012. Mapped versus actual burned area within wildfire perimeters: characterizing the unburned. Forest Ecology and Management 286: 38–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2012.08.020

Krawchuk, M.A., S.L. Haire, J. Coop, M.-A. Parisien, E. Whitman, G. Chong, and C. Miller. 2016. Topographic and fire weather controls of fire refugia in forested ecosystems of northwestern North America. Ecosphere 7(12): e01632. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.1632

Kulakowski, D., C. Mathews, D. Jarvis, and T.T. Veblen. 2013. Compound disturbances in sub-alpine forests in western Colorado favor future dominance by quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides). Journal of Vegetation Science 24: 168–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1654-1103.2012.01437.x

Larson, A.J., R.T. Belote, C.A. Cansler, S.A. Parks, and M.S. Dietz. 2013. Latent resilience in ponderosa pine forest: effects of resumed frequent fire. Ecological Applications 23: 1243–1249. https://doi.org/10.1890/13-0066.1

Larson, A.J., and J.F. Franklin. 2005. Patterns of conifer tree regeneration following an autumn wildfire event in the western Oregon Cascade Range, USA. Forest Ecology and Management 218: 25–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2005.07.015

Leirfallom, S.B., R.E. Keane, D.F. Tomback, and S.Z. Dobrowski. 2015. The effects of seed source health on whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis) regeneration density after wildfire. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 45: 1597–1606. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjfr-2015-0043

Lenoir, J., J.C. Gégout, P.A. Marquet, P. de Ruffray, and H. Brisse. 2008. A significant upward shift in plant species optimum elevation during the 20th century. Science 230: 1768–1771. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1156831

Lentile, L.B., F.W. Smith, and W.D. Shepperd. 2005. Patch structure, fire-scar formation, and tree regeneration in a large mixed-severity fire in the South Dakota Black Hills, USA. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 35: 2875–2885. https://doi.org/10.1139/x05-205

Liang, S., M.D. Hurteau, and A.L. Westerling. 2018. Large-scale restoration increases carbon stability under projected climate and wildfire regimes. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 16: 207–212. https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.1791

Littell, J.S., D. McKenzie, D.L. Peterson, and A.L. Westerling. 2009. Climate and wildfire area burned in western US ecoprovinces, 1916–2003. Ecological Applications 19: 1003–1021. https://doi.org/10.1890/07-1183.1

Lotan, J.E. 1967. Cone serotiny of lodgepole pine near West Yellowstone, Montana. Forest Science 13: 55–59.

Lydersen, J., and M. North. 2012. Topographic variation in structure of mixed-conifer forests under an active fire regime. Ecosystems 15: 1134–1146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-012-9573-8

MacKenzie, M.D., T.H. DeLuca, and A. Sala. 2004. Forest structure and organic horizon analysis along a fire chronosequence in the low elevation forests of western Montana. Forest Ecology and Management 203: 331–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2004.08.003

Malone, S.L., P.J. Fornwalt, M.A. Battaglia, M.E. Chambers, J.M. Iniquez, and C.H. Sieg. 2018. Mixed-severity fire fosters heterogeneous spatial patterns of conifer regeneration in a dry conifer forest. Forests 9: 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/f9010045

Meddens, A.J., C.A. Kolden, J.A. Lutz, J.T. Abatzoglou, and A.T. Hudak. 2018. Spatiotemporal patterns of unburned areas within fire perimeters in the northwestern United States from 1984 to 2014. Ecosphere 9(2): e02029. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.2029

Meigs, G.W., D.C. Donato, J.L. Campbell, J.G. Martin, and B.E. Law. 2009. Forest fire impacts on carbon uptake, storage, and emission: the role of burn severity in the eastern Cascades, Oregon. Ecosystems 12: 1246–1267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-009-9285-x

Meunier, J., P.M. Brown, and W.H. Romme. 2014. Tree recruitment in relation to climate and fire in northern Mexico. Ecology 95: 197–209. https://doi.org/10.1890/13-0032.1

Morgan, J.W., J.D. Vincent, and J.S. Camac. 2018. Upper range limit establishment after wildfire of an obligate-seeding montane forest tree fails to keep pace with 20th century warming. Journal of Plant Ecology 11: 200–207. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpe/rtw130

Morgan, P., M. Moy, C.A. Droske, S.A. Lewis, L.B. Lentile, and P.R. Robichaud. 2014. Vegetation response to burn severity, native grass seeding, and salvage logging. Fire Ecology 11: 31–58. https://doi.org/10.4996/fireecology.1102031

Nagel, T.A., and A.H. Taylor. 2005. Fire and persistence of montane chaparral in mixed conifer forest landscapes in the northern Sierra Nevada, Lake Tahoe Basin, California, USA. Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 132: 442–457. https://doi.org/10.3159/1095-5674%282005%29132%5B442:FAPOMC%5D2.0.CO;2

NIFC [National Interagency Fire Center]. 2018. Homepage. Fire information.. https://www.nifc.gov/fireInfo/fireInfo_statistics.html Accessed 1 July 2018.

North, M.P., J.T. Stevens, T.F. Greene, M. Coppeletta, E.E. Knapp, A.M. Latimer, C.M. Restaino, R.E. Tompkins, K.R. Welch, R.A. York, D.J.N. Young, J.N. Axelson, T.N. Buckley, B.L. Estes, R.N. Hager, J.W. Long, M.D. Meyer, S.M. Ostoja, H.D. Safford, K.L. Shive, C.L. Tubbesing, H. Vice, D. Walsh, C.M. Werner, and P. Wyrsch. 2019. Tamm review: reforestation for resilience in dry western US forests. Forest Ecology and Management 432: 209–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2018.09.007

Ouzts, J., T. Kolb, D. Huffman, and A.S. Meador. 2015. Post-fire ponderosa pine regeneration with and without planting in Arizona and New Mexico. Forest Ecology and Management 354: 281–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2015.06.001

Owen, S.M., C.H. Sieg, A.J.S. Meador, P.Z. Fulé, J.M. Iniguez, L.S. Baggett, P.J. Fornwalt, and M. Battaglia. 2017. Spatial patterns of ponderosa pine regeneration in high-severity burn patches. Forest Ecology and Management 405: 134–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2017.09.005

Paritsis, J., T.T. Veblen, and A. Holz. 2015. Positive fire feedbacks contribute to shifts from Nothofagus pumilio forests to fire-prone shrublands in Patagonia. Journal of Vegetation Science 26: 89–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvs.12225

Parks, S.A., L.M. Holsinger, C. Miller, and C.R. Nelson. 2015. Wildland fire as a self-regulating mechanism: the role of previous burns and weather in limiting fire progression. Ecological Applications 25: 1478–1492. https://doi.org/10.1890/14-1430.1

Parks, S.A., C. Miller, J.T. Abatzoglou, L.M. Holsinger, M.A. Parisien, and S.Z. Dobrowski. 2016a. How will climate change affect wildland fire severity in the western US? Environmental Research Letters 11: 035002. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/11/3/035002

Parks, S.A., C. Miller, L.M. Holsinger, L.S. Bagget, and B.J. Bird. 2016b. Wildland fire limits subsequent fire occurrence. International Journal of Wildland Fire 25: 182–190. https://doi.org/10.1071/WF15107

Passovoy, M.D., and P.Z. Fulé. 2006. Snag and woody debris dynamics following severe wildfires in northern Arizona ponderosa pine forests. Forest Ecology and Management 223: 237–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2005.11.016

Pausas, J.G., J. Llovet, A. Rodrigo, and R. Vallejo. 2008. Are wildfires a disaster in the Mediterranean basin? – A review. International Journal of Wildland Fire 17: 713–723. https://doi.org/10.1071/WF07151

Petrie, M.D., J.B. Bradford, R.M. Hubbard, W.K. Lauenroth, C.M. Andrews, and D.R. Schlaepfer. 2017. Climate change may restrict dryland forest regeneration in the 21st century. Ecology 98: 1548–1559. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.1791

Petrie, M.D., A.M. Wildeman, J.B. Bradford, R.M. Hubbard, and W.K. Lauenroth. 2016. A review of precipitation and temperature control on seedling emergence and establishment for ponderosa and lodgepole pine forest regeneration. Forest Ecology and Management 361: 328–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2015.11.028

Prichard, S., C.S. Stevens-Rumann, and P. Hessburg. 2017. Tamm review: wildland fire-on-fire interactions: management implications under a changing climate. Forest Ecology and Management 396: 217–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2017.03.035

Rehfeldt, G.E., B.C. Jaquish, C. Saenz-Romero, D.G. Joyce, L.P. Leites, J.B.St. Clair, and J. Lopez-Upton. 2014. Comparative genetic responses to climate in the varieties of Pinus ponderosa and Pseudotsuga menziesii: reforestation. Forest Ecology and Management 324: 147–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2014.02.040

Retana, J., J.M. Espelta, A. Habrouk, J.L. Ordenez, and F. Sol-Mora. 2002. Regeneration patterns of three Mediterranean pines and forest changes after a large wildfire in northeastern Spain. Ecoscience 9: 89–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/11956860.2002.11682694

Ritchie, M.W., and E.E. Knapp. 2014. Establishment of a long-term fire salvage study in an interior ponderosa pine forest. Journal of Forestry 112: 395–400. https://doi.org/10.5849/jof.13-093

Roccaforte, J.P., P.Z. Fulé, W.W. Chancellor, and D.C. Laughlin. 2012. Woody debris and tree regeneration dynamics following severe wildfires in Arizona ponderosa pine forests. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 42: 593–604. https://doi.org/10.1139/x2012-010

Rother, M.T., and T.T. Veblen. 2016. Limited conifer regeneration following wildfires in dry ponderosa pine forests of the Colorado Front Range. Ecosphere 7: e01594. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.1594

Rother, M.T., T.T. Veblen, and L.G. Furman. 2015. A field experiment informs expected patterns of conifer regeneration after disturbance under changing climate conditions. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 45: 1607–1616. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjfr-2015-0033

Savage, M., P.M. Brown, and J. Feddema. 1996. The role of climate in a pine forest regeneration pulse in the southwestern United States. Ecoscience 3: 310–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/11956860.1996.11682348

Savage, M., and J.N. Mast. 2005. How resilient are Southwestern ponderosa pine forests to crown fires? Canadian Journal of Forest Research 35: 967–977. https://doi.org/10.1139/x05-028

Savage, M., J.N. Mast, and J.J. Feddema. 2013. Double whammy: high-severity fire and drought in ponderosa pine forests of the Southwest. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 43: 570–583. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjfr-2012-0404

Schoennagel, T., J.K. Balch, H. Brenkert-Smith, P.E. Dennison, B.J. Harvey, M.A. Krawchuk, N. Mietkiewicz, P. Morgan, M.A. Moritz, R. Rasker, and M.G. Turner. 2017. Adapt to more wildfire in western North American forests as climate changes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114: 4582–4590. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1617464114

Serra-Diaz, J.M., C. Maxwell, M.S. Lucash, R.M. Scheller, D.M. Lafower, A.D. Miller, A.J. Tepley, H.E. Epstein, K.J. Anderson-Teixeira, and J.R. Thompson. 2018. Disequilibrium of fire-prone forests sets the stage for a rapid decline in conifer dominance during the 21st century. Scientific Reports 8: 6749.

Shatford, J.P.A., D.E. Hibbs, and K.J. Puettmann. 2007. Conifer regeneration after forest fire in Klamath-Siskiyous: how much, how soon? Journal of Forestry 105: 139–146.

Shive, K.L., H.K. Preisler, K.R. Welch, H.D. Safford, R.J. Butz, K.L. O’Hara, and S.L. Stephens. 2018. From the stand scale to the landscape scale: predicting the spatial patterns of forest regeneration after disturbance. Ecological Applications 28: 1626–1639. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.1756