Abstract

Background

Fibromyalgia is a chronic pain disorder characterized by widespread musculoskeletal symptoms, primarily attributed to sensitization of somatosensory system carrying pain. Few reports have investigated the impact of fibromyalgia symptoms on cognition, corticomotor excitability, sleepiness, and the sleep quality — all of which can deteriorate the quality of life in fibromyalgia. However, the existing reports are underpowered and have conflicting directions of findings, limiting their generalizability. Therefore, the present study was designed to compare measures of cognition, corticomotor excitability, sleepiness, and sleep quality using standardized instruments in the recruited patients of fibromyalgia with pain-free controls.

Methods

Diagnosed cases of fibromyalgia were recruited from the Rheumatology department for the cross-sectional, case-control study. Cognition (Mini-Mental State Examination, Stroop color-word task), corticomotor excitability (Resting motor threshold, Motor evoked potential amplitude), daytime sleepiness (Epworth sleepiness scale), and sleep quality (Pittsburgh sleep quality index) were studied according to the standard procedure.

Results

Thirty-four patients of fibromyalgia and 30 pain-free controls were recruited for the study. Patients of fibromyalgia showed decreased cognitive scores (p = 0.05), lowered accuracy in Stroop color-word task (for color: 0.02, for word: 0.01), and prolonged reaction time (< 0.01, < 0.01). Excessive daytime sleepiness in patients were found (< 0.01) and worsened sleep quality (< 0.01) were found. Parameters of corticomotor excitability were comparable between patients of fibromyalgia and pain-free controls.

Conclusions

Patients of fibromyalgia made more errors, had significantly increased reaction time for cognitive tasks, marked daytime sleepiness, and impaired quality of sleep. Future treatment strategies may include cognitive deficits and sleep disturbances as an integral part of fibromyalgia management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fibromyalgia syndrome is a common neurological condition that is characterized by widespread musculoskeletal pain and the presence of typical tender points throughout the body. The prevalence has been estimated to be up to 1.75% in general population [1] and remains one of the common reasons for rheumatological referrals [2]. Despite many decades of research, the diagnosis and treatment of fibromyalgia remains a contentious topic.

At its core, fibromyalgia is characterized by a heightened pain response to non-nociceptive (allodynia) or nociceptive stimuli (hyperalgesia) [3]. In addition to increased pain, more than 70% of patients of fibromyalgia present a complex symptomatology comprising of fatigue [4], cognitive problems [5, 6], and sleep disturbances [7]. In recognition of their importance, the latest definition of fibromyalgia has undergone major revisions [8, 9]. The driving force of the revision of definition criteria was to broaden the symptom range of patients of fibromyalgia and ease the diagnostic process at the clinical level [10]. From a research point of view, however, the complex symptomatology brings in a few complications: firstly, the symptom profile has become too varied, especially in terms of the nature and extent of co-morbidities; secondly, it can make the management strategy very complicated.

An ongoing experience of pain symptoms is traditionally believed to interfere in the cognitive abilities by limiting the neuronal circuitries available to carry out cognitive functions, especially for attention, psychomotor speed, inhibition, and interference. Thus, a progressive decline in cognitive functions in patients of chronic pain is a logical assumption [11]. Mini-Mental State Examination is a common instrument for assessment of mild cognitive impairments [12]. Stroop test evaluates various components of cognition such as processing speed, selective/task attention, automaticity, and parallel processing [13]. Closely related to musculoskeletal pain is the poor quality of sleep. In fact, self-reported unrefreshed sleep is one of the oldest reported symptoms of fibromyalgia. It is believed that the inability to sleep would lead to daytime excessive sleepiness and easy fatiguability. Several attempts have been made to document cognitive decline [5, 6, 14,15,16,17,18,19] and disrupted sleep [20,21,22,23,24,25,26]; however, the cognitive decline in relation to sleep has not been extensively studied yet.

People with chronic pain often adopt a sedentary lifestyle resulting in a decrease in muscular strength and dysfunction due to the restriction of activities [27, 28]. In addition to myographic changes [29], recent evidence suggests altered structure [30,31,32,33,34] and function [35,36,37] of the motor system in patients of fibromyalgia. Under laboratory conditions, parameters of corticomotor excitability using transcranial magnetic stimulation can be used to quantify changes in the excitability of corticomotor and corticospinal tracts [38]. Few reports have assessed corticomotor excitability in patients of fibromyalgia [39,40,41,42] with conflicting results [43]. The present report is a part of a larger project to investigate the role of putative treatment options for the managmenet of fibromyalgia. However, given the current problem of varied symptomatology, it is imperative to conduct an investigation of the co-morbidities and the relation they share with pain symptoms prior to a clinical trial.

Materials & methods

Study design

It was a cross-sectional case-control study conducted in a tertiary health care centre. Diagnosed patients of fibromyalgia were recruited according to the latest definition, based on 2010/2011 criteria with modifications suggested in 2016, given by the American college of rheumatology [8, 9]. Age- and sex- matched pain-free controls were recruited from following sources: attendees & care-givers of the patients (genetically unrelated), and other hospital staff (unrelated to the study).

Participant recruitment

Right-handed female participants between 18 to 65 years were recruited after taking their medical history. Patients of fibromyalgia and pain-free controls were excluded if they had other chronic diseases such as major psychiatric disorders, autoimmune diseases, rheumatic disease; or were contraindicated to transcranial magnetic stimulation (metallic implants, pacemaker, history of substance abuse, epileptic seizure, head injury or brain surgery, pregnancy, use of antidepressants or anticonvulsants) [44]. All tests were conducted between 09:30 am to 11:30 am in a dedicated assessment laboratory at the same health care centre. The participants were asked to refrain from taking analgesics and other neuro-active substances (caffeine, nicotine, or alcohol) 24 h prior to the investigations. Since hormonal fluctuations could affect these outcomes, the tests were scheduled between the 18th to 23rd days of the menstrual cycle, keeping start of the last menstrual period as the 1st day. Pain characteristics were recorded as intensity of pain (using 11-pt Numerical pain rating scale), number of tender points (using manual palpation), and detailed evaluation of pain perception (using McGill pain questionnaire). Methodological details for pain assessments have been detailed in a recent paper from our group [45].

Cognitive assessment

-

i)

Mini-Mental State Examination; was used to screen mild to moderate impairments in cognitive functions [12]. The vernacular version allows cognitive screening instrument of people of wide literacy and age range [46]. It has 19-items that have a binary response - ‘Yes’ or ‘No’. One mark was given for every correct and zero for an incorrect response resulting in a maximum score of 30. It is a simple bedside test with capacity to examine cognitive functions including attention, registration, orientation, recall, and calculation.

-

ii)

Stroop color-word test; was a cognitive parameter that tests for attention span and task execution [13]. The task was designed and adminstered using SuperLab software (version 5.1; Cedrus Corporation, Arizona, USA) on the computer screen [47]. The initial phase of the test acclimatized the subjects to the monitor, response keys, pattern of the task. It also helped us evaluate adequate color perception, and comprehension of the word. Congruent stimuli were words that meant the same as the color of the font, for example, RED written in red color. While in the incongruent stimuli, the two aspects were mismatched. The principal of the task is that incongruent stimuli generates conflict that is then modulated and resolved by top-down cognitive control. During the test phase, the congruent stimuli were presented interleaved with incongruent stimuli. Participants were asked to correspond to font color (in one block), or word comprehension (in another block) with instructions displayed before each block. The following parameters were recorded for color-word blocks: (a) Accuracy; percentage of correct responses was calculated as the number of correct responses averaged across three trials; (b) Reaction time; average time taken to respond correctly.

Corticomotor excitability

Participants were made to sit on a chair and asked to relax as much as possible with the arm muscles adequately supported with cushions. Scalp landmarks were used to tentatively determine the most excitable region on the scalp overlying the representative area on the motor cortex for the thumb muscles, also known as the ‘motor hotspot’. A figure-of-8 coil (70 mm) transcranial magnetic stimulation (NeuroSoft Neuro-MS/D magnetic stimulator, Ivanovo, Russia; max 4 T) coil was placed such that antero-posteriorly and navigated in small steps to locate the actual ‘hotspot’ of the motor cortex. The point was marked with a pen to ensure the coil position and orientation throughout the experiment. Biphasic pulses were delivered at an interval of 5–7 s [48,49,50].

-

(i)

Resting motor threshold; was defined as the minimum stimulus intensity that elicited an evoked potential with a peak-to-peak amplitude of at least 50 μV in at least five out of ten trials, while maintaining quiescence on the electromyography. Values have been expressed as a percentage of maximum stimulator output.

-

(ii)

Motor evoked potential; was identified as the peak-to-peak amplitude elicited by averaging ten consecutive stimuli [51] acquired at 100% resting motor threshold. Acquisition window for each trial had a width of 100 msec pre-stimulus and 200 msec post-stimulus.

Sleepiness

Sleepiness was measured using Epworth sleepiness scale in subjects. The questionnaire comprised of situations commonly encountered in daily life situations and had four responses to each item. The investigator gave a score to the option wherein, ‘0’ implies ‘would never doze off’, and ‘3’ implies ‘high chances of dozing’, resulting in scoring ranging from 0 to 24. Total scores of Epworth sleepiness scale were obtained by summing the all the responses. It is well established and validated score in Indian population [52].

Sleep quality

Pittsburgh sleep quality index was used to assess sleep quality and disturbances during the month preceding the evaluation. There were 19 individual items, each with four options, in increasing order of severity. Additionally, various aspects of sleep quality like subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleeping medications, and daytime dysfunction have also been reported. Each item is scored on a 0–3 interval scale. The global Pittsburgh sleep quality index score is then calculated by summating the seven component scores, providing an overall score ranging from 0 to 21, where lower scores denote a healthier sleep quality [53]. It also validated in the Indian population with an excellent internal consistency and test-retest reliability [54].

Statistical analysis

Data summary has been presented as the proportions, mean ± standard deviation, or median (q1 – q3). Patients of fibromyalgia and pain-free control groups were compared using Chi-squared goodness-of-fit test, unpaired Student’s t-tests, or Mann-Whitney U-rank tests, as appropriate. The effect size has been presented as partial eta squared (η2) and interpretated as: less than or equal to 0.003 as no effect, 0.10 to 0.039 as small effect, 0.060 to 0.110 as intermediate effect, and 0.140 to 0.200 as large effect [56] Spearman’s rank test was used for correlation of the independent variables. Strength of association was interpreted as: less than 0.1 as a small association, less or equal to 0.3 as a medium association, less than or equal to 0.5 as a large association [55]. P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and all tests were performed using GraphPad Prism version 8.00 for Mac OS (GraphPad Software, California US).

Results

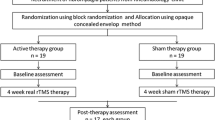

Thirty-four patients of fibromyalgia and 30 pain-free controls were recruited for the study, Fig. 1 shows the details of the recruitment. The mean age was 38.6 ± 9.0 with 80% population being urban (all of controls and 21 of patients). Three-fourths of the population belonged to a middle or higher-middle socioeconomic stratum. All participants were literate, with 26% of the subjects being graduates (9 controls and 8 patients) and 29% being post-graduates (11 controls and 8 patients). No differences were found between patients of fibromyalgia and controls. Table 1 shows the sociodemographic features of the participants.

On average, patients of fibromyalgia reported moderate to severe pain 7.4 ± 1.3 (range 5 to 9) on the 11-point Numerical pain rating scale. The time since the onset of symptoms was 6.8 ± 2.9 years. The total score of McGill pain questionnaire was 32.6 ± 5.3 (range 25 to 48). Clinical examination showed that they had an average of 10.5 ± 2.0 tender points (range 8 to 14). The most common sites of tender points were lower back and calf, forearm and elbow regions. Few patients also reported mild headaches intermittently throughout the day; each bout of pain was felt as dull, boring and aching that often caused the patient to feel extremely tired. The symptoms were aggravated by prolonged sitting, emotional distress, and cold weather. Some degree of relief was felt after using analgesic drugs, local pressure or bandage, and sprays were used to reduce the pain.

Cognitive assessment

There was a significant difference in Mini-Mental State Examination scores of patients of fibromyalgia when compared to controls (p value = 0.054, U-statistic = 382.5, z-score = 4.069, η2 = 0.046, small effect). For the Stroop color-word task, all participants required three familiarity runs before the actual task. There was a significant difference between patients of fibromyalgia and controls in all the four Stroop color-word test parameters. The reaction time for correct answers was prolonged (color: p value < 0.001, U-statistic = 24, z-score = 6.531, η2 = 0.668, intermediate effect | word: p value < 0.001, U-statistic = 27.5, z-score = 6.484, η2 = 0.658, intermediate effect), and the percentage of accuracy was lower for participants with fibromyalgia (color: p value < 0.001, U-statistic = 342.5, z-score = 6.531, η2 = 0.079, intermediate effect | word: p value 0.001, U-statistic = 272.5, z-score = 6.531, η2 = 0.16, small effect).

Corticomotor excitability

Most participants were able to tolerate the transcranial magnetic stimulation pulses comfortably. Resting motor threshold and motor evoked potential amplitudes p value = 0.111, U-statistic = 395, z-score = 4.069, η2 = 0.037, small effect) were found to be statistically comparable between patients of fibromyalgia and pain-free controls. Few participants reported mild headache lasting up to 24 h after the test. No transcranial magnetic stimulation-induced adverse effects were noted.

Sleepiness and sleep quality

There were significant differences in Epworth sleepiness scale scores of fibromyalgia when compared to the controls (p value < 0.001, U-statistic = 207, z-score = 4.069, η2 = 0.724, intermediate effect). Total scores of the Pittsburgh sleep quality index were significantly different (p value < 0.001, U-statistic = 100.5, z-score = 5.502, η2 = 0.046, intermediate effect). On comparing the domains, significant differences were found for sleep quality (p value < 0.001, U-statistic = 142, z-score = 4.944, η2 = 0.474, small effect), latency (p value < 0.001, U-statistic = 22, z-score = 6.558, η2 = 0.673, intermediate effect), duration (p value < 0.001, U-statistic = 81, z-score = 5.764, η2 = 0.52, intermediate effect), efficiency (p value < 0.001, U-statistic = 42.5, z-score = 6.282, η2 = 0.618, intermediate effect), disturbances (p value < 0.001, U-statistic = 60, z-score = 6.047, η2 = 0.573, small effect), medication (p value < 0.001, U-statistic = 450, z-score = 6.047, η2 = 0.046, small effect). Only the daytime sleep was comparable for patients of fibromyalgia and controls (p value 0.116, U-statistic = 48, z-score = 6.208, η2 = 0.604, intermediate effect). Table 2 shows a summary of the comparisons between the pain-free controls and patients of fibromyalgia.

Correlation

No significant correlations were found between pain symptoms (intensity, duration, tender points) and other outcome variables (cognition, corticomotor excitability, or sleep). However, total scores of Mini-Mental State Examination showed a negative correlation with the total score of Pittsburgh sleep quality index (r = − 0.37, p = 0.029). Also, reaction time for word task in Stroop color-word task was negatively correlated with sleep duration (r = − 0.36, p = 0.038) and sleep disturbance (r = − 0.35, p = 0.045) components of Pittsburgh sleep quality index. All three associations were medium in strength.

Discussion

The present study was aimed at investigating the pain-induced symptoms of cognition, corticomotor excitability, sleepiness, and sleep quality in the fibromyalgia patients compared to pain-free controls. Cognition and sleep quality were found to be negatively correlated with each other. No differences were found for the parameters of corticomotor excitability.

The Mini-Mental State Examination indicated that patients of fibromyalgia have mild cognitive impairments; also, the participants performed poorly in all parameters of the Stroop Test. The results show that self-reported cognitive decline (the Mini-Mental State Examination scores) are in concordance with the objective test, the Stroop Test. The study is in line with case-control studies [14] and previous meta-analyses of cognitive deficits in fibromyalgia patients [5, 6]. Imaging studies reported that anterior cingulate cortex and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex are among the main areas involved. Decision making and response evaluation are specific domains controlled by dorsal anterior cingulate cortex. These areas are also reported for pain perception and modulation. Anterior cingulate cortex has vital role in various behavioral responses such as processing of attention and anticipation of pain [56]. This activity may correspond to shared neural pain representations that allow deduction of the affective state of the pain and facilitating empathy [57]. Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex has shown activation, when resolving conflicts and catching errors, also it assists in memory and other executive functions, so ultimately affects cognition. Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is involved in encoding and modulating acute pain perception. Elevated high-frequency oscillatory activities in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and orbito-frontal cortex correspond with higher affective pain scores, cognitive, and emotional modulation of pain in fibromyalgia patients. Structural brain changes in patients of fibromyalgia, indexed using voxel-based morphometry, found that central sensitization is correlated with reduced gray matter volume in specific brain regions such as anterior cingulate cortex and prefrontal cortex [32, 33]. Decreased scores in Stroop test indicates that fibromyalgia symptoms could affected the functioning of anterior cingulate cortex and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.

No significant changes in corticomotor excitability parameters like resting motor threshold and motor evoked potential amplitude were found in patients of fibromyalgia. This is in contradiction to existing literature [39,40,41,42]. The discrepancies in the findings may be attributed to pain characteristics such as chronicity of pain. Latest studies have shown that the time since onset of painful disease could influence the changes in the corticomotor excitability [58]. Another source of dissimilarity could be the methodological differences. Salerno et al., [39] defined resting motor threshold as at least 100 μV amplitude in at least 50% of trials, whereas we used 50 μV cut-off as per the latest guidelines for recording corticomotor excitability by International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology [49]. Another difference was the site of recording taken for our study is the abductor policies brevis, while the earlier studies used first dorsal interossei [39,40,41] or flexor muscle of forearm [42]. Although it is still unclear if using a different muscle group of the hand recording can contribute to the differences in findings [43] or the differences in the patient cohort being tested is the main cause of discrepancy.

Currently available pharmacotherapy for fibromyalgia includes pregabalin, duloxetine, milnacipran, amitriptyline, cyclobenzaprine and tramadol but remain far from satisfactory [59] In the same way, the present cohort of the patients was also allowed to continue the recommended drug as a part of the standard of care [45] (see supplementary file 1). The rationale is based on the fact that these drugs have demonstrated a moderate-to-large effect size for pain symptoms and somewhat on sleep quality, at least in the short term. Evidence suggests that long-term use of neuro-active drugs may induce cognitive deficits. A decline in cognitive ability has also been found to result in interference in daily activities, low coping, and poorer treatment outcomes. If the evidence can be extended to patients of fibromyalgia , then the current management may compound the issue at hand [59,60,61]. But cognitive abilities as outcome measures of the randomized controlled trials are currently missing from the literature. Going forward, an ideal treatment strategy must address pain symptoms and, at least to some degree, the associated co-morbidities.

Limitations

The findings of the study only pertain to middle-aged, regularly menstruating females with fibromyalgia who were refractory to standard of care regime. Factors like age and past treatments can affect pain perception, cognition, and sleep quality. Thus, more studies in patients of fibromyalgia are required to see the generalizability of our findings.

Conclusions

The study confirms a decline in cognitive function and sleep quality in patients of fibromyalgia. Most of the current treatments for fibromyalgia may have some effect on pain perception and to some extent, sleep quality. Introducing adjunct therapies that can help overcome issues of refractoriness and cognitive decline may have better outcomes. More research into treatments that address cognitive deficits vis-à-vis pain and other symptoms need to be conducted.

Availability of data and materials

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and additional information can be provided if requested.

References

Walitt B, Nahin RL, Katz RS, Bergman MJ, Wolfe F. The prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia in the 2012 National Health Interview Survey. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0138024.

Al-Allaf AW, Dunbar KL, Hallum NS, Nosratzadeh B, Templeton KD, Pullar T. A case-control study examining the role of physical trauma in the onset of fibromyalgia syndrome. Rheumatology. 2002;41:450–3.

Üçeyler N, Burgmer M, Friedel E, Greiner W, Petzke F, Sarholz M, et al. Etiology and pathophysiology of fibromyalgia syndrome: updated guidelines 2017, overview of systematic review articles and overview of studies on small fiber neuropathy in FMS subgroups. Schmerz. 2017;31:239–45.

Arnold LM, Clauw DJ, McCarberg BH. Improving the recognition and diagnosis of fibromyalgia. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86:457–64.

Bell T, Trost Z, Buelow MT, Clay O, Younger J, Moore D, et al. Meta-analysis of cognitive performance in fibromyalgia. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2018;40:698–714.

Wu Y-LL, Huang C-JJ, Fang S-CC, Ko L-HH, Tsai P-SS. Cognitive impairment in fibromyalgia: a meta-analysis of case-control studies. Psychosom Med. 2018;80:432–8.

Lawson K. Sleep dysfunction in fibromyalgia and therapeutic approach options. OBM Neurobiol. 2020;4:16.

Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, Goldenberg DL, Häuser W, Katz RL, et al. 2016 revisions to the 2010/2011 fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;46:319–29.

Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, Goldenberg DL, Katz RS, Mease P, et al. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62:600–10.

Häuser W, Ablin J, Perrot S, Fitzcharles MA. Management of fibromyalgia: key messages from recent evidence-based guidelines. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2017;127:47–56.

Hedges D, Farrer TJ, Bigler ED, Hopkins RO, Hedges D, Farrer TJ, et al. Chronic pain and cognition. In: The brain at risk. Basel: Springer International Publishing; 2019. p. 113–24.

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental status”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–98.

Stroop JR. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. J Exp Psychol. 1935;18:643–62.

Rodríguez-Andreu J, Ib̃ez-Bosch R, Portero-Vzquez A, Masramon X, Rejas J, Glvez R. Cognitive impairment in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome as assessed by the mini-mental state examination. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10:162.

Martinsen S, Flodin P, Berrebi J, Lö fgren M, Bileviciute-Ljungar I, Ingvar M, et al. Fibromyalgia patients had normal distraction related pain inhibition but cognitive impairment reflected in caudate nucleus and hippocampus during the Stroop color word test. PLoS One. 2014;9:e108637.

Walteros C, Sánchez-Navarro JP, Muñoz MA, Martínez-Selva JM, Chialvo D, Montoya P. Altered associative learning and emotional decision making in fibromyalgia. J Psychosom Res. 2011;70:294–301.

González JL, Mercado F, Barjola P, Carretero I, López-López A, Bullones MA, et al. Generalized hypervigilance in fibromyalgia patients: an experimental analysis with the emotional Stroop paradigm. J Psychosom Res. 2010;69:279–87.

Suhr JA. Neuropsychological impairment in fibromyalgia: relation to depression, fatigue, and pain. J Psychosom Res. 2003;55:321–9.

Gelonch O, Garolera M, Valls J, Rosselló L, Pifarré J. Executive function in fibromyalgia: comparing subjective and objective measures. Compr Psychiatry. 2016;66:113–22.

Pimentel MJ, Gui MS, Reimão R, Rizzatti-Barbosa CM. Sleep quality and facial pain in fibromyalgia syndrome. J Craniomandib Pract. 2015;33:122–8.

Bigatti SM, Hernandez AM, Cronan TA, Rand KL. Sleep disturbances in fibromyalgia syndrome: relationship to pain and depression. Arthritis Care Res. 2008;59:961–7.

Mutlu P, Zateri Ç, Zöhra A, Özerdoǧan Ö, Mirici AN. Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea in female patients with fibromyalgia. Saudi Med J. 2020;41:740–5.

Choy EHS. The role of sleep in pain and fibromyalgia. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2015;11:513–20.

Keskindag B, Karaaziz M. The association between pain and sleep in fibromyalgia. Saudi Med J. 2017;38:465–75.

Jennum P, Drewes AM, Andreasen A, Neilsen DK. Sleep and other symptoms in primary fibromyalgia and in healthy controls. J Rheumatol. 1993;20:1956–9.

Wu YL, Chang LY, Lee HC, Fang SC, Tsai PS. Sleep disturbances in fibromyalgiaA meta-analysis of case-control studies. J Psychosom Res. 2017;96:89–97.

Nijs J, Daenen L, Cras P, Struyf F, Roussel N, Oostendorp RAB. Nociception affects motor output: a review on sensory-motor interaction with focus on clinical implications. Clin J Pain. 2012;28:175–81.

Chang WJ, O’Connell NE, Beckenkamp PR, Alhassani G, Liston MB, Schabrun SM. Altered primary motor cortex structure, organization, and function in chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain. 2018;19:341–59.

Umay E, Gundogdu I, Ozturk EA. What happens to muscles in fibromyalgia syndrome. Ir J Med Sci. 2020;189:749–56.

Martínez E, Aira Z, Buesa I, Aizpurua I, Rada D, Azkue JJ. Embodied pain in fibromyalgia: disturbed somatorepresentations and increased plasticity of the body schema. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0194534.

Fallon N, Chiu Y, Nurmikko T, Stancak A. Functional connectivity with the default mode network is altered in fibromyalgia patients. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0159198.

Robinson ME, Craggs JG, Price DD, Perlstein WM, Staud R. Gray matter volumes of pain-related brain areas are decreased in fibromyalgia syndrome. J Pain. 2011;12:436–43.

Sundermann B, Dehghan Nayyeri M, Pfleiderer B, Stahlberg K, Jünke L, Baie L, et al. Subtle changes of gray matter volume in fibromyalgia reflect chronic musculoskeletal pain rather than disease-specific effects. Eur J Neurosci. 2019;50:3958–67.

Wood PB, Glabus MF, Simpson R, Patterson JC. Changes in gray matter density in fibromyalgia: correlation with dopamine metabolism. J Pain. 2009;10:609–18.

Gentile E, Brunetti A, Ricci K, Delussi M, Bevilacqua V, M de T. Mutual interaction between motor cortex activation and pain in fibromyalgia: EEG-fNIRS study. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0228158.

Hsiao FJ, Wang SJ, Lin YY, Fuh JL, Ko YC, Wang PN, et al. Altered insula–default mode network connectivity in fibromyalgia: a resting-state magnetoencephalographic study. J Headache Pain. 2017;18:89.

Ichesco E, Quintero A, Clauw DJ, Peltier S, Sundgren PM, Gerstner GE, et al. Altered functional connectivity between the insula and the cingulate cortex in patients with temporomandibular disorder: a pilot study. Headache. 2012;18:89.

Barker AT, Jalinous R, Freeston IL. Non-invasive magnetic stimulation of human motor cortex. Lancet. 1985;325:1106–7.

Salerno A, Thomas E, Olive P, Blotman F, Picot MC, Georgesco M. Motor cortical dysfunction disclosed by single and double magnetic stimulation in patients with fibromyalgia. Clin Neurophysiol. 2000;111:994–1001.

Mhalla A, de Andrade DC, Baudic S, Perrot S, Bouhassira D. Alteration of cortical excitability in patients with fibromyalgia. Pain. 2010;149:495–500.

Caumo W, Deitos A, Carvalho S, Leite J, Carvalho F, Dussán-Sarria JA, et al. Motor cortex excitability and BDNF levels in chronic musculoskeletal pain according to structural pathology. Front Hum Neurosci. 2016;10:357.

Schwenkreis P, Voigt M, Hasenbring M, Tegenthoff M, Vorgerd M, Kley RA. Central mechanisms during fatiguing muscle exercise in muscular dystrophy and fibromyalgia syndrome: a study with transcranial magnetic stimulation. Muscle Nerve. 2011;43:479–84.

Parker R, Lewis G, Rice D, Stimulation PM. Is motor cortical excitability altered in people with chronic pain? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Stimul. 2016;9:488–500.

Klein MM, Treister R, Raij T, Pascual-Leone A, Park L, Nurmikko T, et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation of the brain: guidelines for pain treatment research. Pain. 2015;156:1601–14.

Tiwari VK, Nanda S, Arya S, Kumar U, Bhatia R. Effect of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in male patients of fibromyalgia. Indian J Rheumatol. 2020;15:134–40.

Ganguli M, Ratcliff G, Chandra V, Sharma S, Gilby J, Pandav R, et al. A hindi version of the MMSE: the development of a cognitive screening instrument for a largely illiterate rural elderly population in India. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1995;10:367–77.

Algom D, Chajut E. Reclaiming the stroop effect back from control to input-driven attention and perception. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1683.

Chipchase L, Schabrun S, Cohen L, Hodges P, Ridding M, Rothwell J, et al. A checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies using transcranial magnetic stimulation to study the motor system: an international consensus study. Clin Neurophysiol. 2012;123:1698–704.

Groppa S, Oliviero A, Eisen A, Quartarone A, Cohen LG, Mall V, et al. A practical guide to diagnostic transcranial magnetic stimulation: report of an IFCN committee. Clin Neurophysiol. 2012;123:858–82.

Rossini PM, Rossi S. Transcranial magnetic stimulation: diagnostic, therapeutic, and research potential. Neurology. 2007;68:484–8.

Cavaleri R, Schabrun SM, Chipchase LS. The number of stimuli required to reliably assess corticomotor excitability and primary motor cortical representations using transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2017;6:48.

Bajpai G, Shukla G, Pandey R, Gupta A, Afsar M, Goyal V, et al. Validation of a modified Hindi version of the Epworth sleepiness scale among a north Indian population. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2016;19:499.

Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213.

Manzar MD, Moiz JA, Zannat W, Spence DW, Pandi-Perumal SR, Bahammam AS, et al. Validity of the Pittsburgh sleep quality index in Indian university students. Oman Med J. 2015;30:193–202.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioural science. 2nd ed. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers; 1988.

Fuchs PN, Peng YB, Boyette-Davis JA, Uhelski ML. The anterior cingulate cortex and pain processing. Front Integr Neurosci. 2014;8:35.

Gougeon V, Gaumond I, Goffaux P, Potvin S, Marchand S. Triggering descending pain inhibition by observing ourselves or a loved-one in pain. Clin J Pain. 2016;32:238–45.

Schabrun SM, Christensen SW, Mrachacz-Kersting N, Graven-Nielsen T. Motor cortex reorganization and impaired function in the transition to sustained muscle pain. Cereb Cortex. 2016;26:1878–90.

Calandre EP, Rico-Villademoros F, Slim M. Pharmacological treatment of fibromyalgia: is the glass half empty or half full? Pain Manag. 2017;7:5–10.

Calandre EP, Rico-Villademoros F, Rodríguez-López CM. Monotherapy or combination therapy for fibromyalgia treatment. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2012;14:568–75.

Kravitz HM, Katz RS. Fibrofog and fibromyalgia: a narrative review and implications for clinical practice. Rheumatol Int. 2015;35:1115–25.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Dr. Danveer Bhadu and Dr. Sandeep for patient recruitment, Dr. Ragini Adhikari for scoring the questionnaires, Dr. Suman Tanwar for helping with the review of literatue, Dr. Vinay Chitturi for helping paradigm design, and Ms. Chaithanya Leon for interpreting the Stroop Test analysis.

Funding

No funding to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study was conceived and designed by RB; proposal writing and ethical clearance was obtained by VKT, SN, and RB; standardization of methodology was done by VKT, RS, SSK, and RB; participant diagnosis was done by UK; recruitment of participants was done by VKT and SA; data was acquired by VKT and SA; data processing done by VKT and SN with help of RS, SSK, and RB; statistical analysis was done by VKT and SN. Data interpretation, manuscript writing, and revision was done by all authors. RB takes responsibility for the correspondence, further queries, and guarantee of the study. All authors(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted at the Pain Research and TMS Laboratory, Department of Physiology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India. Human Ethics committee of the AIIMS, New Delhi (Ref No: IECPG-15/16.02.2017RT-27/26.04.2017) approved the research protocol in 2017. The study was also registered in the Clinical Trials Registry of India (CTRI; Ref No: CTRI/2017/09/009827). All procedures performed during study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Human Ethics committee of the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India. Participants were required to sign written, informed consent for the study.

Consent for publication

Consent to publish was also obtained from all the participants included in the study.

Competing interests

No potential conflict of interest was relevant to this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tiwari, V.K., Nanda, S., Arya, S. et al. Correlating cognition and cortical excitability with pain in fibromyalgia: a case control study. Adv Rheumatol 61, 10 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42358-021-00163-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42358-021-00163-x