Abstract

Background

Manganese (Mn) and Selenium (Se) deficiencies are noted in adult patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). However, levels of these trace elements have not been well studied in the paediatric CKD population. We determined the Mn and Se levels in a single-institution cohort of paediatric patients with CKD.

Methods

Ancillary cross-sectional study to a prospective longitudinal randomized control trial on zinc supplementation, which included 42 children and adolescents aged 0 to 19 years with CKD stages I to IV not on dialysis, who had 1–6 trace element measurements. Cystatin C estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the Filler formula. Plasma Mn and Se levels were measured, and anthropomorphic data/blood parameters were collected from electronic health records. The trial was registered on clinicaltrials.gov, NCT02126293.

Results

There were 96 Mn and Se levels in 42 patients (age 12.5 ± 4.6 years). The median Mn concentration was 12.61 nmol/L [10.08, 16.42] with a trend towards lower values with lower eGFR (p = 0.0367 one-sided). Mn z-scores were significantly lower than the general paediatric reference population. The mean Se level was 1.661 ± 0.3399 µmol/L with a significant positive correlation with eGFR (p = 0.0159, r = 0.366). However, only 4 patients with low eGFR had abnormally low Se levels.

Conclusions

This single-institution study of children with CKD demonstrates a significant decrease in Se levels with decreasing eGFR, but no significant difference between mean Se z-scores of our cohort and the reference population. There was no significant relationship between Mn levels and eGFR however the mean Mn z-score was significantly lower than the theoretical mean.

Trial registration: clinicaltrials.gov, NCT02126293, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02126293. Date: April 30, 2014.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Manganese (Mn) and Selenium (Se) are essential trace elements needed for growth and development. In chronic kidney disease, several trace elements are deranged (Filler et al. 2021). Adult and few paediatric studies demonstrated deficiencies in both elements in dialysis-dependent patients (Harshman et al. 2018; Esmaeili and Rakhshanizadeh 2019). Paediatric Mn and Se levels across the entire CKD spectrum are lacking.

Sources of Mn include water, grains, legumes, and nuts (Filler et al. 2021). Mn is bound and transported predominantly by albumin and to a lesser extent by transferrin (Horning et al. 2015). It is involved in immune function, blood sugar, cellular energy regulation, protection against free radicals, and used as a cofactor for various enzymes (Kim et al. 2017). Mn is excreted through faeces, bile, and minimally through the kidneys. It has been shown that osmotic diuresis can enhance the manganese excretion and some children have CKD with tubular salt wasting and substantial osmotic diuresis. In adults Mn levels don’t change much if the eGFR is > 30 mL/min/1.73 m2, but in children this may be different. Adult studies have shown low Mn levels in haemodialysis-dependent patients (Tonelli et al. 2009). Mn deficiency results in poor growth and bone formation, skeletal defects, abnormal glucose tolerance and altered lipid and carbohydrate metabolism in children but is also detrimental for adults (Horning et al. 2015).

As in the case of Mn, sources of Se include water, seafoods, meats, and whole grains (Filler et al. 2021). Se is bound and transported predominantly by selenoproteins and albumin (Filler et al. 2021). It is found in the active centre of glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) and has a role in protecting cell membranes against lipid peroxidation (Harshman et al. 2018). Se is predominantly excreted through glomerular filtration (Filler et al. 2021). Deficiency of Se may result in vascular disease, loss of hair and skin pigmentation, or nutritional cardiomyopathy (Harshman et al. 2018). Adult studies associate worsening Se deficiency with progressive CKD. Se deficiency has been associated with mortality of adult haemodialysis patients (Tonelli et al. 2018).

The objective of this study is to determine the levels of Se and Mn in a cohort of paediatric patients with CKD stages I to IV. We hypothesized that serum Se and Mn would be low in paediatric patients with CKD and that the levels will decrease in direct correlation to eGFR decline.

Materials and methods

Study design and ethics approval

This is an ancillary study from one of the participating centres in a cross-sectional sample that had longitudinal Se and Mn levels measured before and during zinc supplementation. This was a prospective cohort study. Patients were recruited from April 2014 to April 2016. The Research Ethics Board of the University of Western Ontario approved the study as part of an intervention study on Zinc supplementation in patients with CKD cantered at McMaster University (HC #172241; REB #104976).

Parent study

The parent study included patients with CKD Stages 1-IV and renal transplant recipients with declining GFR between the ages of 0 to 18 years who underwent serum trace elements (including Se and Mn) measurements. Children with CKD or kidney transplant were excluded from the parent study.

Study population

Forty-three patients from a single institution in London, Ontario were approached (see Table 1). One patient declined to participate after enrolment, leaving 42 study patients. CKD stage was classified per the KDIGO guidelines [KDIGO, 2009]. Non-dialysis patients with CKD stage I (eGFR > 90 mL/min/1.73 m2) to CKD stage V (< 15 mL/min/1.73 m2) were included in the study. The aetiology of CKD was divided as glomerular and non-glomerular conditions. Since this was an ancillary study, we did not specifically select for the stage of CKD, age, or location of residence. Patients also had different numbers of repeated samples, depending on their clinic visits. Patients were treated as per standard of care with ACE inhibitors, treatment of renal anaemia, renal acidosis, renal osteodystrophy, etc.

Experimental methods

Estimated GFR was calculated using the Filler cystatin C formula (Filler and Lepage 2003). Plasma samples were collected in BD K2-EDTA Royal Blue Vacutainer tubes. Trace element measurements were undertaken both before and during zinc supplementation. Se and Mn levels were measured using High Resolution Sector Field Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry. Reference ranges for Mn are between 7.3–50.2 nmol/L for ages 0–12 months, 14.9–67.0 nmol/L for ages 1–5 years, 5.3–40.8 nmol/L for ages 6–9 years, 7.6–36.4 nmol/L for ages 10–13 years and 8.0- 20.7 nmol/L for ages ≥ 14 years (Pathology and Laboratory Medicine [PaLM], 2017). References ranges for Se are between 0.72–1.21 µmol/L for ages 0–12 months, 1.22–1.82 µmol/L for ages 1–5 years, 1.28–2.04 µmol/L for ages 6–9 years, 1.33–2.03 µmol/L for ages ≥ 10 years (PaLM, 2017). Imprecision of the Mn measurements were 2.7% at low concentration, (65.5 nmol/L), 3.6% at medium concentration (188.7 nmol/L), and 2.7% at high concentration (281.7 nmol/L). Total imprecision (CV) of the Se measurements were 3.6% at low concentration, (1.12 nmol/L), 2.6% at medium concentration (1.62 nmol/L), and 2.3% at high concentration (2.44 nmol/L).

Patients’ height was measured by a stadiometer, for calculation of cystatin C eGFR and their creatinine and cystatin C levels were collected from the hospital electronic chart, PowerChart. Data were entered into Excel for Mac 2011, version 14.4.4.

Statistical methods

Data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5 for Mac OS X, version 5.0f, San Diego, CA, USA. Since most data were normally distributed as tested by the D’Agostino & Pearson omnibus normality test, parametric methods were used for all statistical tests except for Mn and eGFR, which were expressed as median and interquartile range (25th and 75th percentiles). If multiple measurements occurred in each patient, the levels were averaged to avoid a bias of multiple measurements per patient. Since Se and Mn levels are age-dependent, age-independent z-scores were calculated for age and sex based on local reference intervals.

Spearman’s rank correlation analysis was used to analyse the correlation analysis of Se and Mn levels that were not normally distributed. The one sample t-test was used to compare Mn and Se means to the reference mean.

Results

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. There were 96 Mn and Se levels measured in 42 patients (range of 1–6 measurements per patient).

Manganese (Mn)

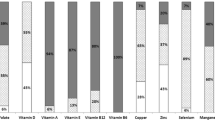

There were six patients (5 females, 1 male) with Mn levels below the lower limit of normal. The eGFR values ranged between 19–89 mL/min/1.73 m2. The median Mn concentration was 12.61 nmol/L (10.08 nmol/L, 16.42 nmol/L). While there was a trend towards lower Mn values with lower eGFR (non-parametric correlation p = 0.0367; one-sided, Spearman r = 0.2791). There was no significant correlation between cystatin C eGFR and the Mn concentration (Fig. 1). The mean age-independent Mn z-score was −0.06509 ± 2.742, was significantly lower than the theoretical mean of 0.0 (p = 0.0222, one sample t-test) shown in Fig. 1.

Selenium (Se)

There were four female patients with Se levels below the lower limit of normal. The eGFR values ranged between 15–73 mL/min/1.73 m2. The median Se concentration was 1.625 µmol/L (1.500 µmol/L, 1.76 µmol/L). The mean Se level was 1.661 ± 0.3399 µmol/L. Linear regression analysis between mean GFR and Se levels was significant (p = 0.0159, r = 0.366, Fig. 1). The mean age-independent Se z-score (0.1577 ± 1.717) was not significantly different than the theoretical mean of 0.0, p = 0.3679, one sample t-test (shown in Fig. 1).

Discussion

This novel study demonstrates a significant decrease in Se levels with decreasing eGFR but no significant difference between mean Se z-scores of our cohort and the reference range. There was no significant relationship between Mn levels and eGFR, however the mean Mn z-score was significantly lower than the theoretical mean.

Se deficiency in CKD can be explained by decreased intake secondary to declining appetite, prescribed dietary restrictions (with lower eGFR), and increased Se and plasma binding protein excretion through the kidneys. Additionally, Se is a component of GSH-Px, an antioxidant enzyme. As reactive oxygen species and reactive nitrogen species accumulate in CKD (Daenen et al. 2019), Se consumption may be increased due to higher GSH-Px activity. These mechanisms progress with worsening CKD represented by decreasing eGFR. However, Se levels were not significantly lower than the reference population. Se is excreted through the glomerulus therefore in the paediatric population where glomerular disease is less prevalent it may be theorized that the prevalence of selenium deficiency is lower than in adults (Filler et al. 2021). While previous adult studies have demonstrated Se deficiency, paediatric studies are scant. One paediatric study found significantly lower Se levels in haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients, as compared to healthy children and children with conservatively treated CKD (Esmaeili and Rakhshanizadeh 2019), similar to our findings. The newfound evidence of Se deficiency associated mortality (Tonelli et al. 2018) suggests that close monitoring and Se supplementation in children with CKD may be warranted. Patients with lower eGFR values may benefit the most from this close monitoring.

Mn has been studied much less than Se in paediatric patients with CKD. Our cohort did not demonstrate a significant decrease in Mn levels with decreased eGFR. This may be due to its predominant faecal and biliary excretion. However, there was a significantly lower z-score of Mn levels as compared to the reference population. Although there is limited renal excretion, the impact of decreased intake and loss of plasma binding proteins in progressive CKD may explain this finding. Furthermore, Mn consumption as part of increased activity of manganese superoxide dismutase and arginase may further explain lower Mn levels (Bresciani et al. 2015). These enzymes play a role in detoxification of reactive oxygen species and ammonia respectively, toxins that accumulate in CKD (Daenen et al. 2019). The impact of these Mn levels needs further elucidation.

Strengths of our study include the cross-sectional design with longitudinal data and the high precision of the instruments used to measure Mn and Se levels. The single-centre nature and the number of patients examined in this study prevent generalization of the results. This study includes a general bias towards milder CKD stages which may underestimate the true prevalence of deficiencies. The authors did not assess baseline variation in dietary consumption, potential supplement intake, or local water content. Finally, while we used reference data, we did not recruit control children without CKD for comparison.

Conclusions

This study adds important information of Mn and Se levels for paediatric patients with CKD and corroborates previous adult-focused studies that have shown Se deficiency in relationship with decreasing eGFR. Se and Mn are important trace minerals that ensure appropriate growth and development in the growing child and our findings support the monitoring of levels of these trace elements in paediatric patients with CKD. Further research is required to better understand the extent of Se deficiency in paediatric patients with decreased renal function.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- Mn:

-

Manganese

- Se:

-

Selenium

References

Bresciani G, da Cruz IB, González-Gallego J (2015) Manganese superoxide dismutase and oxidative stress modulation. Adv Clin Chem 68:87–130

Daenen K, Andries A, Mekahli D, Van Schepdael A, Jouret F, Bammens B (2019) Oxidative stress in chronic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol 34:975–991

Esmaeili M, Rakhshanizadeh F (2019) Serum trace elements in children with end-stage renal disease. J Renal Nutr 29:48–54

Filler G, Lepage N (2003) Should the Schwartz formula for estimation of GFR be replaced by cystatin C formula? Pediatr Nephrol 18:981–985

Filler G, Qiu Y, Kaskel F, McIntyre CW (2021) Principles responsible for trace element concentrations in chronic kidney disease. Clin Nephrol 96:1–16

Harshman LA, Lee-Son K, Jetton JG (2018) Vitamin and trace element deficiencies in the pediatric dialysis patient. Pediatr Nephrol 33:1133–1143

Horning KJ, Caito SW, Tipps KG, Bowman AB, Aschner M (2015) Manganese is essential for neuronal health. Annu Rev Nutr 35:71–108

Kim M, Koh ES, Chung S, Chang YS, Shin SJ (2017) Altered metabolism of blood manganese is associated with low levels of hemoglobin in patients with chronic kidney disease. Nutrients 9:1177

Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Hemmelgarn B, Klarenbach S, Field C, Manns B, Thadhani R, Gill J, Alberta Kidney Disease N (2009) Trace elements in hemodialysis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med 7:25

Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Bello A, Field CJ, Gill JS, Hemmelgarn BR, Holmes DT, Jindal K, Klarenbach SW, Manns BJ, Thadhani R, Kinniburgh D, Alberta Kidney Disease N (2018) Concentrations of trace elements and clinical outcomes in hemodialysis patients: a prospective cohort study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13:907–915

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patients and their families for participating in this study.

Funding

This study was supported through funding from Hamilton Health Sciences in the form of a New Investigator Fund Award (NIF13312) which was awarded to Dr. Vladimir Belostotsky.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SV and GF developed this study from the original study led by VB. SV and GF wrote the drafts, developed the figure, conducted the statistical analysis, made multiple edits, added content, and approved the final version. VB conducted the original study, provided intellectual input to the various versions, and approved the final version. LY helped conduct the statistical analysis, provided intellectual input to the various versions, and approved the final version. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee at which the studies were conducted (HC #172241; REB #104976) and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants or substitute decision makers included in the study. This included consent for publication of the results.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Verma, S., Belostotsky, V., Yang, L. et al. Plasma manganese and selenium levels in paediatric chronic kidney disease patients measured by high resolution sector field inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Bull Natl Res Cent 47, 22 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42269-023-00996-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42269-023-00996-0