Abstract

Background

The surgical ciliated cyst of the maxilla was initially reported as a sequela of Caldwell–Luc type open maxillary sinus procedures. Recently, other etiologies have become apparent and cases have been reported outside of the maxilla. They have the potential for local destruction and at times may mimic a locally aggressive tumor or cyst. We aim to elucidate the etiopathogenesis of the surgical ciliated cyst to improve prevention, diagnosis and treatment of these lesions.

Body

A systematic review of the literature using PubMed and Scopus databases was conducted to assess the presentation, treatment, and outcomes of this disease. Surgical ciliated cysts of the maxillofacial region shows a 1.1:1 female-to-male ratio with a protracted time to diagnosis (range: 4–22 years). Typically, radiology shows a unilocular radiolucency (95%) and histology predominantly shows pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium (58%). The most common treatment of these lesions involves enucleation and curettage. In rare instances, transfacial approaches, resection, and reconstruction are required. Recurrence ranges from 6 to 20%.

Conclusion

Surgical ciliated cyst should be considered in a patient presenting with an orofacial mass or edema who has a history of maxillofacial injury or surgery. Timely diagnosis will decrease the severity and morbidity associated with this entity. Meticulous surgical technique can aid in the prevention of this lesion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The postoperative maxillary cyst (POMC) was first reported in the literature by Kubo et al. (1927). Unaware of the lesion’s prior description, Gregory and Shafer reported three cases in 1958 as “surgical ciliated cyst of the maxilla (SCCM).” (Gregory and Shafer 1958) Further publications ensued, initially mostly in the Japanese literature (Kubo and Shida 1961; Mizutani et al. 1974; Mohri et al. 1977; Odawara 1965; Sato et al. 1969; Hashimoto et al. 1987; Nakamura et al. , 1075; Fukuta et al. 1987; Kaneko et al. 1989; Sawano et al. 2005; Yamada et al. 1991; Shik 1989; Yang et al. 2018; Kuroishikawa 2000; Yu and Lin 1998; Toda et al. 1990). However, it is now well documented across geographical regions (Coviello et al. 2016; Koo Min Chee et al. 2014; Moe et al. 2013; Kaneshiro et al. 1981; Yoshikawa et al. 1982; Yamamoto and Takagi 1986; Basu et al. 1988; Miller et al. 1988; Sugar et al. 1990; Misch et al. 1991; Hayhurst et al. 1993; Hasegawa and Kuroishikawa 1993; Nastri and Hookey 1994; Józefowicz-Korczyńska and Latkowski 1995; Lockhart et al. 2000; Imholte and Schwartz 2001; Yoshizaki and Watanabe 2002; Koutlas et al. 2002; Amin et al. 2003; Lazar et al. 2003; Bartnik and Bartnik-Krystalska 2004; Bourgeois and Nelson 2005; Shakib et al. 2009; Cano et al. 2009; Ragsdale et al. 2009; Bulut et al. 2010; Leung et al. 2012; Kim et al. 2013; Fernandes et al. 2013; Lee et al. 2014; An and Zhang 2014; Li et al. 2014; Toyoshima et al. 2014; Cai et al. 2015; Adachi et al. 2016; Niederquell et al. 2016; Yamamoto et al. 2017; Martinelli-Kläy et al. 2017; Matsuzaki et al. 2017; Han 2018; Tanio et al. 2019; Golaszewski et al. 2019; Siwach et al. 2020; Pe et al. 1990; Kondo et al. 2018; Heo et al. 2000; Gang et al. 2014; Yamaura et al. 2005).

The traditionally accepted pathogenesis of SCCMR involves entrapment of nasal or maxillary sinus mucosa, a subsequent inciting inflammatory process, and progressively increased osmotic pressure. Together, these steps lead to cyst creation, expansion, and enlargement. Early publications detailed this event occurring most often as a sequelae of open maxillary sinus surgery (Kubo and Shida 1961; Mizutani et al. 1974; Mohri et al. 1977; Odawara 1965; Sato et al. 1969; Hashimoto et al. 1987; Nakamura et al. , 1075; Fukuta et al. 1987; Kaneko et al. 1989; Sawano et al. 2005; Yamada et al. 1991; Shik 1989; Yang et al. 2018; Kuroishikawa 2000; Yu and Lin 1998; Toda et al. 1990). The advent of functional endoscopic sinus surgery has decreased the incidence of this etiology. However, the entrapment of nasal or sinus mucosa within a facial fracture or osteotomy line remains a common cause. As such, the etiology of surgical ciliated cysts has evolved to include: The transplantation of respiratory mucosa to the mandible during combined rhinoplasty/genioplasty, contamination of surgical instruments in double jaw surgery, and the improper management of nasal or sinus mucosal perforation in dental implant surgery. This has led to the discovery of surgical ciliated cysts outside of the maxilla (Kubo 1927; Sawano et al. 2005; Yu and Lin 1998; Hayhurst et al. 1993; Yoshizaki and Watanabe 2002).

The clinical presentation depends upon the location of cyst formation, direction of growth, size, and amount of bone loss or resorption. It may present as a palpable swelling or mass in the mucobuccal fold of the maxilla or mandible, the palate, naso-orbital region, or midface. Extragnathic presenting symptoms may include facial deformity, nasal obstruction, orbital proptosis, or visual changes. As it can be found anywhere within the facial skeleton, the name surgical ciliated cyst of the maxillofacial region (SCCMR) seems more inclusive.

The incidence of the SCCMR is not well known. Basu et al. reported an incidence of SCCMR of approximately 1.5% of all oral cysts encountered in their institution’s pathology registry. Their publication provides great detail in the classic findings of SCCMR and how to distinguish it from other entities on a histopathologic and microbiologic basis (Yu and Lin 1998).

To better understand and characterize this often unrecognized entity, we have undertaken a systematic review of SCCMR.

Materials and methods

A systematic review of the literature was conducted using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) method (Moher et al. 2009). Our intent was to search the literature for all patient-related cases of SCCMR. PubMed (MEDLINE) and Scopus were queried using the following terms: “surgical ciliated cyst” OR “postoperative maxillary cyst” OR “surgical implantation cyst” or “respiratory implantation cyst.” All results from inception of the registry to August 18, 2020, were included.

Articles were screened by the first author J.C.G. and results reviewed independently by authors J.C.G and E.C. Any discrepancies were reviewed and settled with verbal discussion. Studies were included for review if the (a) title and abstract included the desired search terms; (b) abstract contained patient-related data; (c) abstract was equivocal, full article review revealed patient case(s).

Articles were excluded if (a) the article reported on a different type of cyst, neoplasm or disease; (b) there was redundant reporting of clinical cases; (c) the article described only the surgical treatment of the cyst or related lesion without patient data; (c) the article only described the histopathology of the disease; (d) the article type was a letter to the editor, book chapter, opinion, or poster; (e) both the abstract and article were not available.

After completion of the abstract review, the references for included publications were screened and cross checked for any additional studies that met inclusion criteria. A total of 50 publications were included (Fig. 1).

Clinical information was compiled into tables in Microsoft Word including: total number of cases, age, gender, etiology, duration from inciting factor to diagnosis, clinical, radiologic, and histologic findings, and treatment. A summary of the data is presented (Tables 1, 2) and the details are presented as Additional file 1: Appendix 1–4.

Results

Fifty publications and 205 cases of surgical ciliated cyst were included. They were all retrospective, level 4 evidence. One hundred of the cases included gender information, with a 1.1:1 female-to-male ratio. Ninety-eight cases provided definitive etiology regarding the cause of the SCCMR (Table 1). In some case series, the etiologies were listed but not matched to patient presentation or treatment and were therefore left out, leaving only approximately one half of the publications for analysis. Only two cases were presented as being spontaneous in nature with an incidence of 1% and we believe these to be likely from unrecognized inciting event.

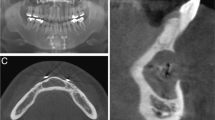

In our review, the predominant clinical presenting features are: mucobuccal and facial edema following Caldwell Luc type procedures; palatal, mucobuccal or mandibular swelling from orthognathics (Fig. 2A); facial or orbital edema with potential for nasal or visual disturbance from trauma; or maxillary or mandibular mucobuccal fold edema from sinus lift and dental procedures (Kuroishikawa 2000). The latency period (Table 1) in our analysis was calculated as the interval from inciting traumatic event or surgery to diagnosis.

A Example of a clinical presentation of a surgical ciliated cyst in a 41-year-old female with painful, infected palatal mass like edema ten years post-Le Fort 1 maxillary orthognathic surgery. B Radiologic correlate in this axial bone window of a CT facial bones scan shows typical radiologic findings of surgical ciliated cyst: expansile unilocular radiolucent lesion which originates from maxillary fixation screws and plate

The most common radiologic presentation was that of a homogenous, corticated, unilocular radiolucency (95.5%), with cortical perforation occurring 23% of the time (Fig. 2B).

SCCMR is by definition characterized by respiratory epithelium (Figs. 3, 4). All SCCMR is therefore pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium and the only relevant histologic findings are the presence or absence of metaplasia within the cyst. When provided, we found a predominance of respiratory type epithelium alone (58%) with cuboidal and squamous metaplasia occurring less frequently (36%).

Several studies presented case matched details on treatment rendered (Table 2 and Additional file 1: Appendix 5). Enucleation and curettage alone was the most commonly employed treatment (56%).

Discussion

SCCMR is a destructive, postsurgical, or post-traumatic lesion which may mimic other cysts and tumors of the maxillofacial region, given its ability to cause bone and hard tissue loss. It should be suspected in someone with prior craniomaxillofacial surgery, or trauma, presenting with mass-like edema or pain, or a radiolucent lesion in the site of prior surgery. The latency time can be very long, spanning up to several decades from inciting events to clinical presentation. The predominant histologic finding in our review is that of pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium. Other, less common pathologic findings include squamous and cuboidal metaplasia with goblet cells.

Severe cases often exhibit extensive local bone loss, cortical perforation, fistula formation, or extension into nearby anatomic structures such as the maxillary sinus, nasal cavity, orbit, and adjacent facial bones (Kuroishikawa 2000; Józefowicz-Korczyńska and Latkowski 1995; Bartnik and Bartnik-Krystalska 2004; Leung et al. 2012; Golaszewski et al. 2019; Kusunoki and Ikeda 2012). This is corroborated by others who note that their initial clinical suspicion was of a more destructive or even malignant lesion (Józefowicz-Korczyńska and Latkowski 1995; Bartnik and Bartnik-Krystalska 2004). Kusunoki et al. describe a large maxillary sinus lesion they presumed to be a SCCMR due to the extent of maxillary bone loss, yet upon histologic examination, it was found to be neuroendocrine carcinoma (Kusunoki and Ikeda 2012).

Time to diagnosis for these patients was found to be a mean range of five to 22 years depending upon etiology (Table 1). This is consistent with another recent review by Golaszewski et al., which showed a 15.83-year average latency time (Golaszewski et al. 2019). Fernandes et al. published a case report in 2013 that exemplifies the nuances in the diagnosis of SCCMR. In their publication, the patient developed symptoms five years after surgery and endured 10 years of unsuccessful multiple incision and drainage procedures as well as medical treatment with antibiotics. The diagnosis was finally made 15 years later, when the lesion had grown and caused significant bone loss (Fernandes et al. 2013).

An initial treatment algorithm was proposed by Yoshikawa et al. which included: enucleation and curettage alone, enucleation with primary closure, marsupialization, or open packing (Yoshikawa et al. 1982). Other treatments have been described since this early publication including: irrigation and curettage (Sawano et al. 2005; Koutlas et al. 2002), Le Fort 1 down fracture for access (Hayhurst et al. 1993), transfacial approach via lateral rhinotomy for en bloc resection (Adachi et al. 2016), and endoscopic sinus surgery (Yang et al. 2018). The authors believe that prompt surgical treatment of this disease should be completed upon its recognition. Treatment goals should include the removal of the entire cystic lining, in an en bloc fashion if possible. With this in mind, curettage and ostectomy with a surgical handpiece should be employed as adjuvant measures to ensure all epithelial remnants are removed. In addition, any hardware or foreign body that may have caused mucosal entrapment should be removed to treat the source of the cyst. Access for the surgery may be possible in transoral fashion for most cases; however, some may require trans-facial approach. The surgeon may also consider an endoscopic approach as long as it does not prohibit en bloc removal of the cyst, curettage, ostectomy, and hardware removal. Recurrence is thought to occur with incomplete removal of the cyst lining and is reported to range from 6 to 20% (Yoshikawa et al. 1982; Li et al. 2014; Lee and Lee 2010). More specifically, Yoshikawa et al. reported seven recurrences out of 110 cases; however, they did not correlate to treatment rendered (Yoshikawa et al. 1982). Finally, any delay in surgical treatment for conservative therapies such as marsupialization, packing, irrigation, injection, or aspiration will only delay the diagnosis and time to definitive surgical treatment. This may incur increased morbidity to the patient.

Prevention of SCCMR may be possible with meticulous surgical technique, including: suturing torn nasal mucosa (Hayhurst et al. 1993); removing/stripping sinus mucosa during orthognathic or facial trauma procedures (Kühnel and Reichert 2015); cleaning/changing the saw blades after maxillary osteotomy (Bourgeois and Nelson 2005); close inspection and thorough irrigation of osteotomies to flush entrapped mucosa (Bourgeois and Nelson 2005); doing mandible surgery first (Bourgeois and Nelson 2005); abstaining from the use of residual maxillary or nasal bone autograft for use in the mandible or any other sites (Cai et al. 2015); preventing mucosal impaction in fractured segments (An and Zhang 2014); and meticulous maintenance of the Schneiderian membrane in sinus lift (Yamamoto and Takagi 1986).

While our review is the largest attempt to characterize and provide both preventative, diagnostic, and treatment recommendations for SCCMR, it has limitations. First, there are many articles in other languages or older texts that were not obtainable. This presents a reporting bias. Second, not every case report or series was reported uniformly. Therefore, some cases are missing demographic or clinical information. Third, this data is all presented retrospective fashion which may lead to selection bias of only cases reported that were significant or notable. Finally, the larger case series reported their findings as cohorts, whereas case reports and case series reported specific case details for each patient (Kaneshiro et al. 1981; Basu et al. 1988). This made it difficult to pool data regarding etiology from the case reports with the data from the larger case series.

Conclusions

Consideration of SCCMR in the differential diagnosis of a patient with prior maxillofacial injury or surgery presenting with orofacial mass, edema, or incidental radiolucency is important. Prompt recognition and consideration in the differential diagnosis will aid in decreasing the time to diagnosis, morbidity, and severity of these lesions. Treatment via enucleation and curettage with source control should be completed upon diagnosis, though more aggressive measures may be needed. This article should also serve to remind practitioners of the ways in which meticulous surgical technique can aid in the prevention of the formation of this lesion altogether.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- SCCMR:

-

Surgical ciliated cyst of the maxillofacial region

- POMC:

-

Postoperative maxillary cyst

- SCCM:

-

Surgical ciliated cyst of the maxilla

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis

References

Adachi M, Miyata Y, Ito Y (2016) Mid-facial deformity secondary to a traumatic haemorrhage in a maxillary cyst. J Surg Case Rep 2016(2):rjw013

Amin M, Witherow H, Lee R, Blenkinsopp P (2003) Surgical ciliated cyst after maxillary orthognathic surgery: report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 61(1):138–141

An J, Zhang Y (2014) Surgical ciliated cyst of the medial canthal region after the management of a midfacial fracture: a case report. J Craniofac Surg 25(2):701–702

Bartnik W, Bartnik-Krystalska A (2004) Postoperative maxillary cyst. Otolaryngologia Polska the Polish Otolaryngology 58:641–643

Basu MK, Rout PG, Rippin JW, Smith AJ (1988) The post-operative maxillary cyst: experience with 23 cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 17(5):282–284

Bourgeois SL Jr, Nelson BL (2005) Surgical ciliated cyst of the mandible secondary to simultaneous Le Fort I osteotomy and genioplasty: report of case and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 100(1):36–39

Bulut A, Sehlaver C, Perçin AK (2010) Postoperative maxillary cyst: a case report. Patholog Res Int 2010:810835

Cai M, Shen G, Lu X, Wang X (2015) Two mandibular surgical ciliated cysts after Le Fort I osteotomy and genioplasty. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 53(10):1040–1042

Cano J, Campo J, Alobera MA, Baca R (2009) Surgical ciliated cyst of the maxilla: clinical case. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 14(7):E361-364

Coviello V, Dehkhargani S, Patini R, Cicconetti A (2016) Surgical ciliated cyst 12 years after Le Fort I maxillary advancement osteotomy: a case report and review of the literature. Oral Surg 10:165–170

Fernandes KS, Gallottini MHC, Felix VB, Santos PSS, Nunes FD (2013) Surgical ciliated cyst of the maxilla after maxillary sinus surgery: a case report. Oral Surg 6(4):229–233

Fukuta M, Han DH, Yamasoba T, Ishibashi T, Shoji M, Iinuma T (1987) CT analysis of the postoperative cyst of the maxilla. Nihon Jibiinkoka Gakkai Kaiho 90(12):1922–1926

Gang TI, Huh KH, Yi WJ, Lee SS, Heo MS, Choi SC (2014) The effect of radiographic imaging modalities and the observer’s experience on postoperative maxillary cyst assessment. Imaging Sci Dent 44(4):301–305

Golaszewski J, Muñoz R, Barazarte D, Perez L (2019) Surgical ciliated cyst after maxillary orthognathic surgery: a literature review and case report. Oral Maxillofac Surg 23(3):281–284

Gregory GT, Shafer WG (1958) Surgical ciliated cysts of the maxilla: report of cases. J Oral Surg (chic) 16(3):251–253

Han YS (2018) Postoperative maxillary cyst developing after sinus augmentation for dental implants: a rare case report. Implant Dent 27(2):260–263

Hasegawa M, Kuroishikawa Y (1993) Protrusion of postoperative maxillary sinus mucocele into the orbit: case reports. Ear Nose Throat J 72(11):752–754

Hashimoto M, Takahashi E, Tamakawa Y, Katoh T (1987) CT of postoperative maxillary cyst. Rinsho Hoshasen 32(1):27–31

Hayhurst DL, Moenning JE, Summerlin DJ, Bussard DA (1993) Surgical ciliated cyst: a delayed complication in a case of maxillary orthognathic surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 51(6):705–708 (discussion 708–709)

Heo S-M, Song MY, Lee SS, Choi SC, Park TW (2000) A comparative study of the radiological diagnosis of postoperative maxillary cyst. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 29:347–351

Imholte M, Schwartz HC (2001) Respiratory implantation cyst of the mandible after chin augmentation: report of case. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 124(5):586–587

Józefowicz-Korczyńska M, Latkowski B (1995) Postoperative maxillary cyst. Otolaryngol Pol 49(4):359–363

Kaneko K, Kishikawa T, Matsuo Y, Matsumoto S, Kudo S, Mizuguchi M (1989) Computed tomographic diagnosis of postoperative maxillary cyst (POMC)–a comparison with conventional tomography. Nippon Igaku Hoshasen Gakkai Zasshi 49(10):1236–1242

Kaneshiro S, Nakajima T, Yoshikawa Y, Iwasaki H, Tokiwa N (1981) The postoperative maxillary cyst: report of 71 cases. J Oral Surg 39(3):191–198

Kim JJ, Freire M, Yoon JH, Kim HK (2013) Postoperative maxillary cyst after maxillary sinus augmentation. J Craniofac Surg 24(5):e521-523

Kondo K, Baba S, Suzuki S, Nishijima H, Kikuta S, Yamasoba T (2018) Infraorbital nerve located medially to postoperative maxillary cysts: a risk of endonasal surgery. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec 80(1):28–35

Koo Min Chee CA, Brierley DJ, Hunter KD, Pace C, McKechnie AJ (2014) Surgical ciliated cyst of the maxilla following maxillary osteotomy: a case report. Oral Surg 7(1):39–41

Koutlas IG, Gillum RB, Harris MW, Brown BA (2002) Surgical (implantation) cyst of the mandible with ciliated respiratory epithelial lining: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 60(3):324–325

Kubo I (1927) A buccal cyst occurred after a radical operation of the maxillary sinus. Z Otol Tokyo 33:896

Kubo M, Shida A, Kishi K (1961) Treatment of disturbances of smell by means of chondroitin sulfate. Jibiinkoka 33:131–133

Kühnel TS, Reichert TE (2015) Trauma of the midface. GMS Curr Top Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg 14:Doc06

Kuroishikawa Y (2000) Clinical study of ocular symptoms in 21 cases with post-operative maxillary Cysts. 耳鼻咽喉科展望. 43(5):393–397

Kusunoki T, Ikeda K (2012) Neuroendocrine carcinoma arising in a wound of the postoperative maxillary sinus. Clin Pract 2(1):34–36

Lazar F, ZurHausen M, Siessegger A, Mischkowski R, Zöller JE (2003) Mucocele of the chin area: a rare complication after genioplasty with osteocartilagenous nasal bone transplant: review of the literature and case report. Mund Kiefer Gesichtschir 7(6):380–385

Lee KC, Lee NH (2010) Comparison of clinical characteristics between primary and secondary paranasal mucoceles. Yonsei Med J 51(5):735–739

Lee JH, Huh KH, Yi WJ, Heo MS, Lee SS, Choi SC (2014) Bilateral postoperative maxillary cysts after orthognathic surgery: a case report. Imaging Sci Dent 44(4):321–324

Leung YY, Wong WY, Cheung LK (2012) Surgical ciliated cysts may mimic radicular cysts or residual cysts of maxilla: report of 3 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 70(4):e264-269

Li CC, Feinerman DM, MacCarthy KD, Woo SB (2014) Rare mandibular surgical ciliated cysts: report of two new cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 72(9):1736–1743

Lockhart R, Ceccaldi J, Bertrand JC (2000) Postoperative maxillary cyst following sinus bone graft: report of a case. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 15(4):583–586

Martinelli-Kläy CP, Chatelain S, Salvado F, Lombardi T (2017) Respiratory epithelium lined cyst of the maxilla: differential diagnosis. Case Rep Pathol 2017:6249649

Matsuzaki Y, Kaneko T, Makita E et al (2017) Postoperative maxillary cyst presenting as a skin tumour on the cheek. Eur J Dermatol EJD 27:433–434

Miller R, Longo J, Houston G (1988) Surgical ciliated cyst of the maxilla. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 46(4):310–312

Misch CM, Misch CE, Resnik RR, Ismail YH, Appel B (1991) Post-operative maxillary cyst associated with a maxillary sinus elevation procedure: a case report. J Oral Implantol 17(4):432–437

Mizutani A, Hachiya J, Iinuma T (1974) Mucocele-type of the postoperative cysts of the maxilla. Practica Otol 67:707–710

Moe JS, Magliocca KR, Steed MB (2013) Early maxillary surgical ciliated cyst after L e F ort I untreated for 20 years. Oral Surg 6(4):224–228

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6(7):e1000097

Mohri M, Nishio M, Mohri J, Shimazu K, Akane K, Asai R (1977) Problems relating to postoperative maxillary cyst. Nippon Jibiinkoka Gakkai Kaiho 80(4):326–333

Nakamura K, Kitani S, Sato H, Yumoto E, Kawakita S, Aibara R (1995) Endoscopic endonasal surgery for postoperative maxillary cyst. Nippon Jibiinkoka Gakkai Kaiho 98(6):984–988

Nastri AL, Hookey SR (1994) Respiratory epithelium in a mandibular cyst after grafting of autogenous bone. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 23(6 Pt 1):372–373

Niederquell B-M, Brennan PA, Dau M, Moergel M, Frerich B, Kämmerer PW (2016) Bilateral postoperative cyst after maxillary sinus surgery: report of a case and systematic review of the literature. Case Rep Dent 2016:6263248

Odawara K (1965) Study on the healing of the maxillary sinus after the radical operation. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol Tokyo 8:96–107

Pe MB, Sano K, Kitamura A, Inokuchi T (1990) Computed tomography in the evaluation of postoperative maxillary cysts. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 48(7):679–684

Ragsdale BD, Laurent JL, Janette AJ, Epker BN (2009) Respiratory implantation cyst of the mandible following orthognathic surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol 13(1):30–34

Sato T, Shiota S, Nakanishi H, Tsukamoto K (1969) Statistical study of the postoperative maxillary cyst at Kyoto University Hospital. Kyoto Daigaku Kokukagaku Kiyo 9(3):141–153

Sawano M, Kanazawa Y, Sasaki T et al (2005) Postoperative maxillary cyst with orbital reconstruction. Folia Ophthalmologica Japonica 56:981–984

Shakib K, McCarthy E, Walker DM, Newman L (2009) Post operative maxillary cyst: report of an unusual presentation. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 47(5):419–421

Shik CK (1989) The post-operative maxillary cyst: report of 14 cases. Taehan Chikkwa Uisa Hyophoe Chi 27(11):1049–1057

Siwach P, Joy T, Gaikwad S, Meshram V (2020) Postoperative maxillary cyst. Indian J Dent Res 31(1):157–159

Sugar AW, Walker DM, Bounds GA (1990) Surgical ciliated (postoperative maxillary) cysts following mid-face osteotomies. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 28(4):264–267

Tanio S, Tamura T, Kasuya H et al (2019) Surgical ciliated cyst developing after Le Fort I osteotomy: case report and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg Med Pathol 31(6):410–414

Toda N, Nakanishi H, Nagae H, Tanaka S, Kikuchi M, Shigemi H (1990) A case of postoperative maxillary cyst. Nishinihon J Dermatol 52(2):263–267

Toyoshima T, Tanaka H, Kitamura R, Kiyoshima T, Shiratsuchi Y, Nakamura S (2014) Traumatic ciliated cyst derived from zygomaticomaxillary fracture: Report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg Med Pathol 26:175–178

Yamada M, Yoshiura K, Okuda H, Izumi M, Ueno H, Yamada N (1991) An analysis of the postoperative maxillary cyst using computed tomography. Oral Radiol 7:21–30

Yamamoto H, Takagi M (1986) Clinicopathologic study of the postoperative maxillary cyst. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 62(5):544–548

Yamamoto S, Maeda K, Kouchi I et al (2017) Surgical ciliated cyst following maxillary sinus floor augmentation: a case report. J Oral Implantol 43(5):360–364

Yamaura M, Sato T, Echigo S, Takahashi N (2005) Quantification and detection of bacteria from postoperative maxillary cyst by polymerase chain reaction. Oral Microbiol Immunol 20(6):333–338

Yang HC, Kang SH, Yoon SH, Cho HH (2018) Transnasal endoscopic removal of bilateral postoperative maxillary cysts after aesthetic orthognathic ssurgery: differences from that of Caldwell-Luc operations. Auris Nasus Larynx 45(3):608–612

Yoshikawa Y, Nakajima T, Kaneshiro S, Sakaguchi M (1982) Effective treatment of the postoperative maxillary cyst by marsupialization. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 40(8):487–491

Yoshizaki T, Watanabe A (2002) Endoscopic endonasal sinus surgery for post-operative maxillary cysts. Nihon Jibiinkoka Gakkai Kaiho 105(9):931–936

Yu L, Lin C (1998) Postoperative maxillary cyst. J Otolaryngol Soc Republic China 33(5):447–451

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LG worked on conceptualization, composition of manuscript, and final approval. DT worked on methodology and final approval. JG worked on conceptualization, composition of manuscript, methodology, literature search, and final approval. MT worked on conceptualization and final approval. EC worked on literature search, composition of manuscript, and final approval. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The subjects of this study are publications on the topic of surgical ciliated cyst and therefore no consent or permission required.

Consent for publication

Patient consent obtained for disclosure of clinical photographs.

Competing interests

The authors have no financial or proprietary conflicts to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Appendices. Appendix 1. Surgical Ciliated Cyst of the Maxillofacial Region Demographics. Appendix 2. Clinical Presentation of SCCMR Systematic Review. N= number of patients, NA = not available. Appendix 3. Radiologic Presentation of SCCMR. Appendix 4. Histologic Presentation of SCCMR. Appendix 5. SCCMR Treatment.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gates, J.C., Taub, D.I., Cherkas, E. et al. Surgical ciliated cyst of the maxillofacial region: a systematic review. Bull Natl Res Cent 46, 235 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42269-022-00925-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42269-022-00925-7