Abstract

Purpose

To outline the process of the STABILISE technique and its use; reporting patient outcomes and midterm follow up for complicated aortic dissection.

Materials and methods

Single centre retrospective analysis from January 2011 to January 2021 using the STABILISE technique which utilises balloon assistance to facilitate intimal disruption and promote aortic relamination.

Results

Sixteen patients underwent endovascular aortic repair with the STABILISE technique for aortic dissection over the study period. Fourteen patients (14/16; 88%) had acute dissection. Two of 16 (12%) were chronic. The median age of the patient cohort was 61 years (range 32–80 years) and consisted of a male majority (n = 11; 69%). The median time from diagnosis to intervention was 5 days (1–115 days; IQR 1–17.3). More than half (56%) had surgical repair of a acute type A aortic dissection prior to radiological intervention. The procedure was technically successful with no procedural mortality. Two patients were lost to follow up and two died in the post-operative period. Twelve patients had ongoing follow up with an average number of 2.9 ± 1.6 scans performed. Follow up was available in thirteen patients (81%) with a median follow up period of 1097 days (IQR 707–1657). The rate of re-intervention (n = 2/16; 13%) requiring additional stenting was in line with published re-intervention data (15%). Follow up showed a reduction in false lumen size following treatment with total luminal dimensions remaining stable over the follow-up period.

Conclusion

The STABILISE technique as a procedure for complicated aortic dissection, either acute or chronic, appears safe with stable mid-term aortic remodelling and patient outcomes.

Level of evidence

Level 3, Retrospective cohort study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

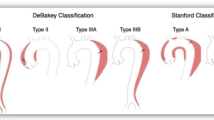

Aortic dissection is an important cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Acute aortic dissection, occurring within a 2 week period of symptom onset (Nienaber & Powell, 2012) is part of the spectrum of acute aortic syndrome. This also includes intramural haematoma, penetrating aortic ulcer and symptomatic or ruptured aortic aneurysm. (Erbel et al., 2014) The two common classifications for aortic dissection include the DeBakey system (types I, II and III) (Debakey et al., 1965) and the Stanford systems (types A and B) (Daily et al., 1970), these are classified based on involvement of the ascending aorta (DeBakey I-II, Stanford A) or sparing the ascending aorta and arch vessels (DeBakey III, Stanford B).

First described in 1994 by Dake et al., (Dake et al., 1994) thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) and abdominal endovascular aortic repair (EVAR) have been widely used in the management of acute aortic syndromes. Endovascular repair provides benefit as it avoids major surgical incisions, aortic cross-clamping, reduces procedural time, decreases blood loss, and decreases end-organ ischaemia. (Dangas et al., 2012; Walsh et al., 2008) Reduced post-operative mortality (30 day; 7.9% vs 20% and 1 year; 8.7% vs 17%), in addition to reduced procedural complications, have also been demonstrated in those undergoing TEVAR compared with open repair (Harky et al., 2020; Hsieh et al., 2019). Despite these benefits, meta-analyses have shown TEVAR to be associated with pooled reintervention rates of 15%; reasons including, endoleak (33.2%), false-lumen perfusion and aortic dilation (19.8%), and new dissection (6.9%). (Faure et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2016).

In an attempt to promote aortic remodelling and eliminate false lumen perfusion, Hofferberth et al. (Hofferberth et al., 2014) introduced “stent assisted balloon-induced intimal disruption and relamination in aortic dissection repair” (STABILISE). The approach aims to produce a single aortic channel in the thoracic/distal aorta using a compliant balloon to extend the fenestration along the length of the dissected segment and reoppose the layers of the dissected aortic wall using self-expanding stents. Two similar approaches performed prior to STABILISE were the PETTICOAT (Provisional Extension to Induce Complete Attachment) (Mossop et al., 2005; Nienaber et al., 2006; Rong et al., 2019) and STABLE (Staged Total Aortic and Branch Vessel Endovascular) (Hofferberth et al., 2012b) techniques. The PETTICOAT technique provided internal support to the intima from within the true lumen, reducing intimal flap motion. This lowered the risk of new tears at the distal end of the covered stent, and reduced movement of blood within the false lumen promoting stasis and thrombosis. This approach was effective in reducing the risk of aneurysmal dilatation of the thoracic false lumen. The STABLE technique established further reduction in false lumen flow by occluding remaining small fenestrations using covered stents, coils, and vascular plugs. It had been shown to be effective in controlling abdominal as well as thoracic false lumen growth but was technically difficult and typically required multiple procedures over an extended time period. Both used proximal covered and distal bare stents but did not include balloon fenestration. The STABLE technique included the use of branch vessel covered stents and other techniques for closing any remaining communications between the true and false lumens. More recently, the STABLE II technique has been published demonstrating improved outcomes post treatment of acute complicated type B aortic dissection. (Lombardi et al., 2020)

As a novel technique, publications and case numbers utilising the STABILISE technique remain small in volume. A retrospective review by Faure et al. in 2018 (Faure et al., 2018) sought to validate the initial findings by the Hofferberth group assessing 41 patients. Their results supported the STABILISE approach as a safe and reproducible technique with encouraging midterm results.

In this study, we report the outcomes of a consecutive series of patients undergoing the STABILISE technique for complicated aortic dissection at a quaternary teaching hospital in Australia.

Methods

A single-centre retrospective review was undertaken for all patients who underwent endovascular management for aortic dissection using the STABILISE technique (intimal balloon fenestration and attempt aortic relamination as described above). Ethics approval was granted by the local institutional ethics and review board; reference number HREC/53590. STROBE cohort reporting guidelines have been utilised. (von Elm et al., 2008)

Patients

Between January 2011 to January 2020, all patients who underwent endovascular repair (EVAR and TEVAR) for type A and B dissection using the STABILISE technique were included in the study. Indications for intervention included aortic rupture, visceral organ malperfusion, progressive false lumen growth of more than 5 mm over serial computed tomographic (CT) scans, total aortic dimension of more than 40 mm, refractory hypertension and persistent pain. STABILISE was utilised in patients if there was persistent false filling after initial deployment of a covered aortic stent. Patient details including demographics, dissection morphology, prior interventional history, operation details and post-operative follow-up were recorded.

Endovascular procedure and prosthesis

The Zenith Dissection Endovascular System (Cook Medical Inc., Bloomington, Ind) is a modular system specifically designed to treat aortic dissection, consisting of a proximal component, the Zenith TX2 TAA Endovascular Graft, and a distal component, the Zenith Dissection Endovascular Stent. A detailed description of the Zenith Dissection Endovascular System has been previously reported. (Hofferberth et al., 2012a; Melissano et al., 2008; Mossop et al., 2005).

Technique

The procedure is performed under general anaesthesia in an Angiography suite or hybrid theatre with DSA imaging. A 6 French sheath is placed in the left common femoral artery (CFA) and a 5 Fr 100 cm measuring pigtail catheter advanced over a guidewire into the aortic true lumen proximal to the dissection, commonly into the ascending aorta. Right common femoral artery access is gained either surgically or percutaneously using a preclose technique with Perclose ProGlide system™ (Abbott). Using an 8Fr arterial sheath, an angled catheter and Terumo glidewire® (Terumo) are advanced through the true lumen to the ascending aorta and the wire exchanged for a 300 cm double curve Lunderquist® extra-stiff wire (Cook). The Zenith TX2 stent graft (covered stent) is introduced percutaneously over the Lunderquist wire and deployed in a landing zone more proximal to the proximal extent of the dissection. Zenith Dissection (uncovered) Stents (Cook) are then deployed with approximately 20 mm overlap throughout the dissected aortic segment. Care is taken to avoid stent overlap in the visceral segment of the abdominal aorta. Balloon dilatation (Coda® balloon; Cook) commences within the TX2 (covered) stent graft using the 46 mm Coda® balloon and is continued sequentially in an overlapping pattern through the stent graft and bare stent, changing to the 32 mm balloon as required depending on distal aortic diameter. When dissection continues into the common iliac arteries, these are treated using large self-expanding nitinol stents (Zilver® Vena; Cook). Balloon dilatation within iliac arteries is achieved either with an angioplasty balloon sized to the total iliac diameter or gentle partial inflation of the 32 mm Coda® balloon. Balloon dilatation is achieved via a pressure inflator titrating balloon expansion whilst simultaneously screening via fluoroscopy. The authors found the balloon setup described above to work consistently with most patients, changing balloon diameters distally within the aorta/iliacs according to arterial dimensions unique to each patient.

Depending on aortic angiogram appearances, the visceral arteries were stented with balloon expandable stents either covered or uncovered to treat tear extension into these branches.

Aortic remodelling

Aortic remodelling post-STABILSE was evaluated using the index pre-preprocedural and subsequent follow-up imaging studies. Aortic cross-sectional diameters and luminal values were measured, including true lumen, false lumen, and total luminal transverse dimensions on standard axial acquisitions. The aortic level measurements were standardised to include the level of the carinal bifurcation, coeliac artery origin, renal artery origin at the midpoint of the left and right renal ostium and at the aortic bifurcation (iliac vessel origins). Cross-sectional area orthogonal to the centreline of the vessel was obtained using post-processing software suite (AGFA IMPAX® client) (see Figs. 1, 2 and 3).

Data analysis

Data was assessed for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk normality test and expressed as numbers (%) for categoric values and median (interquartile [IQR] range) or mean (± standard deviation) for continuous variables. As the data was not normally distributed (i.e., non-parametric), Mann-Whitney U testing was utilised to analyse the continuous variables.

Results

Sixteen patients underwent endovascular aortic repair with the STABILISE technique for aortic dissection over the study period (2011–2020). The median age of the patient cohort was 61 years (range 32–80 years) and consisted of a male majority (n = 11; 69%). The median time from diagnosis to intervention was 5 days (1–115 days; IQR 1–17.3). A breakdown of the Type A and B cases are demonstrated below in Table 1.

Nine of sixteen patients (56%) had surgical repair of the acute type A aortic dissection prior to radiological intervention. One of the acute type A presentations had a previous Bentall’s procedure for congenital bicuspid valve (n = 1; 6%). One patient with a previous history of type A repair had a diagnosis of Marfan’s syndrome, presenting acutely with a Type B dissection One patient had prior sternotomy for coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). Table 2 outlines the patient demographics and details of the dissection morphology, vessels involved, and vessels stented.

Clinical follow up

Pre-procedural imaging was available in 14 of 16 patients (87%). Two patients died within 30 days of the procedure (day 1 and day 27). One patient (acute type A) died due to multiple associated medical problems including pulmonary haemorrhage, end-organ ischaemia and marked coagulopathy whilst the second patient (acute type B) died from complications of renal ischaemia and failure, which preceded the STABILISE intervention. More recent larger sample studies assessing treatment of acute type B dissection have demonstrated 30-day mortality at 6.8%. (Lombardi et al., 2020)

Two patients were lost to follow up, one at 87 days, the other at 3.5 years post procedure.

The average number of scans performed for patient follow up was 2.9 ± 1.6 scans. Follow up was available in thirteen patients (81%) with a median follow up period of 1097 days (IQR 707–1657).

No patient deaths were recorded from 30 days post procedure until the end of the review period (January 2020). One patient (8%) required further operative intervention to manage delayed endo-leak at 5.8 years post initial procedure. The remaining 12 patients were free from procedure-related complications including stent rupture, stent migration, vessel occlusion or re-dissection.

Aortic remodelling

Figures 4, 5, 6 and 7 outline the aortic area measurements, including diameter and area in the pre-and post-intervention period in those treated successfully. In line with previously reported studies, the maximum aortic dimensions were observed in the thoracic aorta at the level of the carina, with pre interventional mean aortic areas measuring 15 ± 15 cm2.

A late increase in diameter at the carinal level was noted in a single case with persistent endoleak (Fig. 8). The other 12 cases with long term follow up all showed a reduction in false lumen size following treatment. Total luminal dimensions remained stable over the follow-up period, allowing for an increased carinal level area measurement secondary to the endo-leak described above, which required re-intervention. True lumen area and total aortic dimensions, accounting for the increased false luminal diameter in the re-operated patient were otherwise stable with no significant dilatation; p = 0.83 [> 0.05]; (Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric testing).

Aortic reintervention

Two out of the sixteen patients (13%) required further intervention to manage false lumen enlargement. Both patients had filling of the false lumen at the time of follow up scanning. One patient was retreated 14 days after the initial procedure with deployment of an additional stent graft. The other patient with the delayed endoleak (Fig. 8) had two further treatments, at 286 and 2066 days post procedure. The first treatment was deployment of an Amplatzer™ Vascular Plug II (Abbott Vascular) occluder device in the left subclavian artery to prevent retrograde filling of the false lumen. Subsequently, a stent graft was deployed to completely obliterate the false lumen in the thoracic aorta. No new sites of dissection were identified in the interventional group through follow up imaging. The graphs detailed above demonstrate the evolving false lumen in the patient described above.

Discussion

The high technical success rate and safety profile of this STABILISE cohort is in keeping with previous results. (Hofferberth et al., 2012a) A review of the current literature outlined below (see Tables 3 and 4) summarises the use of STABILISE technique in complicated aortic dissection.

In our series, medium term survival was excellent. Aortic dimensions remained stable through the study period (up to 5 years). Re-intervention was required in 2 patients for persistent endoleak. Failure to successfully control the endoleak in one of the patients was associated with ongoing growth of the false lumen and total aortic diameter. This reinforces the role of complete false lumen exclusion in successful management of this condition. Ongoing clinical and radiological follow up remains important to detect and manage any persistent growing false lumen. Further, there was no commonality in endoleak location between the two patients, as one was seen along the most inferior margin of the aortic stent, the other at the thoracic junction. Our rate of re-intervention was similar to meta-analyses described above suggesting 15% re-treatment. (Zhang et al., 2016) No long term sequalae have been identified in the two patients who required reintervention. When performed with open surgical repair for acute type A dissection, the STABILISE technique did not add morbidity. Although our study has shown a 12.5%, 30 day mortality rate, no direct deaths were attributed to the STABILISE procedure. Both deaths were secondary to pre-existing ischaemia and organ dysfunction. It is difficult to infer meaningful comparison to more recent studies demonstrating a 6.8% mortality post STABILISE (Lombardi et al., 2020) given small sample size of complicated type B dissection in our study cohort (n = 5). No peri-procedural complications including groin haematoma or iatrogenic arterial dissection were identified.

Although most of the patients were treated in the acute phase, two chronic dissections were treated successfully at 90 days and 115 days. Other reports suggest that treatment beyond this time may be associated with difficulty in disrupting the intimal flap although still safe and efficacious. () The authors consider the hyperacute phase (within 24–48 h) post dissection to carry too high of a risk of aortic rupture whilst delayed treatment in the chronic phase, considered after 12 weeks, reduces intimal pliability and possible successful relamination. In any case, careful balloon remodelling with high dose fluoroscopy and wire control is paramount in ensuring appropriate fenestration. Another reason for avoiding late treatment is the difficulty in managing aortic dilation due to the inability to obtain an appropriate stent graft apposition site once the distal thoracic aorta diameter approaches 46 mm. Despite risks of aortic rupture, there is limited data published substantiating this risk with only one rupture identified in the literature during aortic remodelling. (Zhong et al., 2021) STABILISE has also been utilised in cases of connective tissue disease (Soler et al., 2021) with authors suggesting close follow up due to aneurysmal evolution at the bare stent level.

The aim of STABILISE technique goes beyond the PETTICOAT technique with the goal of complete false lumen obliteration. Although STABLE also aims to completely obliterate false lumen flow, STABILISE is a simpler more stereotyped technique which is more easily applied to a range of patients and operator experience. Using a compliant balloon to extend fenestration along the whole length of the dissected segment and bare stents to reappose the intimal flap to the outer media restores physiological pressure and flow to a single aortic lumen. This appears to remove the pathophysiological processes which drive progressive false lumen dilatation in the abdominal aorta as well as the thoracic false lumens.

Although the results are favourable and on par with other centres from around the world, we acknowledge the limitations of a small sample size and single centre retrospective experience. Further single and multi-centre studies would be useful.

Conclusion

The STABILISE technique as a procedure for complicated aortic dissection either acute or chronic appears safe with stable mid-term aortic remodelling and patient outcomes. The rate of re-intervention in our series is in line with published data. The STABILISE procedure can be considered where there is extensive dissection necessitating reconstitution of inline aortic flow. Further multi-centre prospective studies would be of use to validate the indications and long-term outcome.

Availability of data and materials

Yes

Abbreviations

- TEVAR:

-

Thoracic endovascular aortic repair

- EVAR:

-

Endovascular aortic repair

- STABILISE:

-

Stent assisted balloon induced intimal disruption and relamination in aortic dissection repair

- PETTICOAT:

-

Provisional Extension to Induce Complete Attachment

- STABLE:

-

Staged Total Aortic and Branch Vessel Endovascular

- CABG:

-

Coronary artery bypass grafting

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

References

Daily PO, Trueblood HW, Stinson EB, Wuerflein RD, Shumway NE (1970) Management of acute aortic dissections. Ann Thorac Surg 10(3):237–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-4975(10)65594-4

Dake MD, Miller DC, Semba CP, Mitchell RS, Walker PJ, Liddell RP (1994) Transluminal placement of endovascular stent-grafts for the treatment of descending thoracic aortic aneurysms. N Engl J Med 331(26):1729–1734. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199412293312601

Dangas G, O'Connor D, Firwana B, Brar S, Ellozy S, Vouyouka A, Arnold M, Kosmas CE, Krishnan P, Wiley J, Suleman J, Olin J, Marin M, Faries P (2012) Open versus endovascular stent graft repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 5(10):1071–1080. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2012.06.015

Debakey ME, Henly WS, Cooley DA, Morris GC Jr, Crawford ES, Beall AC Jr (1965) Surgical management of dissecting aneurysms of the aorta. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 49(1):130–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5223(19)33323-9

Erbel R, Aboyans V, Boileau C, Bossone E, Bartolomeo RD, Eggebrecht H, Evangelista A, Falk V, Frank H, Gaemperli O, Grabenwöger M, Haverich A, Iung B, Manolis AJ, Meijboom F, Nienaber CA, Roffi M, Rousseau H, Sechtem U, Sirnes PA, Allmen RS, Vrints CJ, ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (2014) 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases: document covering acute and chronic aortic diseases of the thoracic and abdominal aorta of the adult. The task force for the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 35(41):2873–2926. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehu281

Faure EM, Canaud L, Agostini C, Shaub R, Böge G, Marty-ané C, Alric P (2014) Reintervention after thoracic endovascular aortic repair of complicated aortic dissection. J Vasc Surg 59(2):327–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2013.08.089

Faure EM, El Batti S, Abou Rjeili M, Julia P, Alsac JM (2018) Mid-term outcomes of stent assisted balloon induced intimal disruption and Relamination in aortic dissection repair (STABILISE) in acute type B aortic dissection. European J Vasc Endovascr Surg : the official journal of the European Society for Vascular Surgery 56(2):209–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejvs.2018.04.008

Faure EM, El Batti S, Sutter W et al (2020) Stent-assisted balloon dilatation of chronic aortic dissection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 162(5):1467–1473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2020.01.081

Harky A, Bleetman D, Chan JSK, Eriksen P, Chaplin G, MacCarthy-Ofosu B, Theologou T, Ambekar S, Roberts N, Oo A (2020) A systematic review and meta-analysis of endovascular versus open surgical repair for the traumatic ruptured thoracic aorta. J Vasc Surg 71(1):270–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2019.05.011

Hofferberth SC, Foley PT, Newcomb AE, Yap KK, Yii MY, Nixon IK, Wilson AM, Mossop PJ (2012a) Combined proximal Endografting with distal bare-metal stenting for Management of Aortic Dissection. Ann Thorac Surg 93(1):95–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.06.106

Hofferberth SC, Newcomb AE, Yii MY, Yap KK, Boston RC, Nixon IK, Mossop PJ (2012b) Combined proximal stent grafting plus distal bare metal stenting for management of aortic dissection: superior to standard endovascular repair? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 144(4):956–962. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.07.007

Hofferberth SC, Nixon IK, Boston RC, McLachlan CS, Mossop PJ (2014) Stent-assisted balloon-induced intimal disruption and relamination in aortic dissection repair: the STABILISE concept. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 147(4):1240–1245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.03.036

Hsieh RW, Hsu TC, Lee M, et al. (2019) Comparison of type B dissection by open, endovascular, and medical treatments. Journal of vascular surgery, 70(6):1792-1800.e1793

Lombardi JV, Gleason TG, Panneton JM et al (2020) STABLE II clinical trial on endovascular treatment of acute, complicated type B aortic dissection with a composite device design. J Vasc Surg 71(4):1077–1087 e1072

Melissano G, Bertoglio L, Kahlberg A, Baccellieri D, Marrocco-Trischitta MM, Calliari F, Chiesa R (2008) Evaluation of a new disease-specific endovascular device for type B aortic dissection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 136(4):1012–1018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.06.021

Mossop PJ, McLachlan CS, Amukotuwa SA, Nixon IK (2005) Staged endovascular treatment for complicated type B aortic dissection. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med 2(6):316–321. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncpcardio0224

Nienaber CA, Kische S, Zeller T, Rehders TC, Schneider H, Lorenzen B, Bünger CM, Ince H (2006) Provisional extension to induce complete attachment after stent-graft placement in type B aortic dissection: the PETTICOAT concept. J Endovasc Ther 13(6):738–746. https://doi.org/10.1583/06-1923.1

Nienaber CA, Powell JT (2012) Management of acute aortic syndromes. European heart journal, 33(1):26-35b

Rong D, Ge Y, Liu J, Liu X, Guo W (2019) Combined proximal descending aortic endografting plus distal bare metal stenting (PETTICOAT technique) versus conventional proximal descending aortic stent graft repair for complicated type B aortic dissections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 10. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013149.pub2

Soler R, Bartoli MA, Amabile P, Sarlon-Bartoli G, Magnan P-É (2021) STABILISE for Complicated Type B Dissection after 15 Months’ Follow Up: A Word of Caution. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 62(1):138–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejvs.2021.02.025

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP (2008) The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol 61(4):344–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008

Walsh SR, Tang TY, Sadat U, Naik J, Gaunt ME, Boyle JR, Hayes PD, Varty K (2008) Endovascular stenting versus open surgery for thoracic aortic disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of perioperative results. J Vasc Surg 47(5):1094–1098. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2007.09.062

Zhang L, Zhao Z, Chen Y, et al. (2016) Reintervention after endovascular repair for aortic dissection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery, 152(5):1279-1288.e1273

Zhong J, Osman A, Tingerides C, Puppala S, Shaw D, McPherson S, Darwood R, Walker P (2021) Technique-based evaluation of clinical outcomes and aortic Remodelling following TEVAR in acute and subacute type B aortic dissection. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 44(4):537–547. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-020-02749-2

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge and thank the editors at CVIR endovascular for their time on this project.

Funding

No funding for the project has been obtained either via institutional grants or personal funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Each author has contributed in part during the study, either by study design, data collection, manuscript formation and revisions. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Yes; Ethics ID HREC53590.

Consent for publication

Yes

Competing interests

Nil competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mitreski, G., Flanders, D., Maingard, J. et al. STABILISE; treatment of aortic dissection, a single Centre experience. CVIR Endovasc 5, 7 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42155-022-00286-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42155-022-00286-2