Abstract

Background

Intraperitoneal instillation of local anesthetics provides effective postoperative pain control after laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC). This study was aimed to evaluate the analgesic effect and effects on postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) of intraperitoneal ropivacaine alone and with dexamethasone in patients undergoing LC. In this randomized, prospective, double-blinded, observational clinical study, a total of 100 patients scheduled for LC were randomized into two equal groups. Group RD (n = 50) received 0.2% ropivacaine 30 ml plus 8 mg dexamethasone, and group RS (n = 50) received 0.2% ropivacaine 30 ml plus 2 ml normal saline intraperitoneally at the end of surgery through the trocar. Pain score was monitored using a numeric rating scale (NRS) at 0, 1, 2, 4, 6, 12, and 24 h postoperatively. The primary objective of the study was to compare the pain intensity between the groups. The secondary objectives were to compare the time to first rescue analgesia, total dose of rescue analgesic in 24 h, incidence of PONV, and side effects if any between the groups.

Results

A significant difference in mean NRS score was observed among two groups at 6, 12, and 24 h. Only 52% in group RD demanded rescue analgesia as compared to 76% in group RS (P = 0.0004). Incidence of PONV was significantly lower in the RD group than in the RS group. No significant adverse effects were found.

Conclusions

The addition of 8 mg dexamethasone to intraperitoneal ropivacaine (0.2%) significantly prolongs the time of first rescue analgesic requirement and reduces the total consumption of rescue analgesic in 24 h. It significantly reduces the incidence of PONV in LC as compared to ropivacaine use alone.

Trial registration

The clinical trial is registered under Clinical Trials Registry—India

Registration no.: CTRI/2021/10/037206

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) for cholelithiasis has replaced the open approach because of faster recovery and early discharge from the hospital. Although greatly decreasing the need for analgesia, these techniques still cause visceral nociception, through disruption of the peritoneum and dissection of viscera (Chundrigar et al. 1993).

Different modalities have been introduced to relieve postoperative pain. These include parenteral analgesics such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), opioids, and interpleural and intercostal nerve blocks as well as intraperitoneal LA and opioids.

The ease of use and safety of local anesthetics is well recognized, and collectively they act as one of the most important classes of drugs in perioperative care.

Local anesthetics are commonly used by skin infiltration or epidural administration in abdominal surgery, blocking somatic afferents and providing significant benefits in reducing postoperative pain and improving recovery. It is also possible, however, to instill local anesthetic solutions into the peritoneal cavity, hence blocking visceral afferent signaling and potentially modifying visceral nociception and downstream illness responses.

Instillation of intraperitoneal lignocaine, bupivacaine, levobupivacaine, and ropivacaine has been used following laparoscopic gynecological and general surgical procedures to reduce postoperative pain through randomized trials for many years. Use of adjuvant drugs in combination with intraperitoneal instillation of local anesthetic has been found to reduce postoperative pain following laparoscopic cholecystectomy more effectively (Kumhar and Mayank 2020).

A noteworthy prolongation of time length of analgesia had been stated when dexamethasone was supplemented in epidural, caudal (Parameswari et al. 2017), subarachnoid blocks and brachial plexus blocks (Dar et al. 2013).

Bupivacaine is associated with cardiotoxicity when used in high concentration or when accidentally injected intravascularly. Ropivacaine is an S(−) enantiomer that is structurally related to bupivacaine and has less toxicity. Hence, in our study, we preferred ropivacaine over bupivacaine. From these data, the present study was undertaken for assessing and comparing the efficacy of intraperitoneal instillation of ropivacaine (0.2%) alone and ropivacaine (0.2%) plus dexamethasone (8 mg) in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The primary outcome of the study was to compare the severity of pain by NRS. The secondary outcomes included time of the first rescue analgesia, need for total dose of rescue analgesic in 24 h, and antiemetic requirement and any adverse effects following the study intervention.

Methods

This prospective randomized study was conducted after obtaining approval from institutional research ethical committee (GCSMC/EC/Research project/APPROVE/2021/264). The clinical trial registration was done before the start of the study (CTRI/2021/10/037206). All the principles of the Helsinki Declaration were followed during the study course. After taking patient’s written informed consents, this double-blind study included total of 100 patients. Randomization was done by computer-generated system, and those giving the drug as well as those receiving the drug were unaware about the exact drug. All patients were randomly allocated to one of the two equal groups (50 patients each) using a computer-generated table of randomization. The list was concealed in sealed envelopes that were numbered and opened sequentially after obtaining patient’s consent. Group RD patients received intraperitoneal 0.2% ropivacaine 30 ml plus 8 mg dexamethasone (total 32 ml), and group RS received intraperitoneal 0.2% ropivacaine 30 ml plus 2 ml normal saline (total 32 ml) (Fig. 1).

All patients were evaluated at preoperative anesthesia clinic. The NRS pain scale was explained to the patients during preoperative checkup. The inclusion criteria included the patients who were posted for elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy under general anesthesia, able to interpret the NRS score with an American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) physical status I and II, aged 18–70 years of either gender with body mass index (BMI) 18–30 kg m−2, and duration of surgery up to 2 h. Patients with allergy or contraindicated to study drugs, BMI > 30 kgm−2, who are pregnant, who have hepatobiliary malignancies, who have laparoscopy converted to open cholecystectomy, and who have presence of acute cholecystitis, choledocholithiasis, portal hypertension, or compromised systemic illness were excluded from study.

Standard monitors were applied in the operative room, and an intravenous line was secured with 18G intracath. All patients of both groups received general anesthesia. Premedication drug injection of glycopyrrolate 0.2 mg, injection of ondansetron 8 mg, intravenous antibiotic, and injection of fentanyl 100 mcg were given. Patients were induced with injection of propofol 2 mg/kg and injection of suxamethonium 2 mg/kg. Intraoperative maintenance was done with O2, air, and sevoflurane. For muscle relaxation, injection of atracurium 0.5 mg/kg blous followed by maintenance 0.1mg/kg was used. Injection of paracetamol 1 gm was given intraoperatively.

Study drugs were prepared by an anesthesiologist not involved in the study. The anesthesiologist who observed the patient was unaware of the study drug. After completion of the surgery, group RD received injection of ropivacaine (0.2%) 30 ml with injection of dexamethasone (8 mg) 2 ml, while group RS received injection of ropivacaine (0.2%) 30 ml with injection of NS 2 ml total volume 32 ml instilled via trocar in the gallbladder fossa in Trendelenburg position, and this position was kept for 5 min. After that, all trocars were removed, and extubation was done.

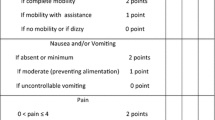

In the postoperative room, patients were assessed for pain using the NRS score at rest and at movement. There were complaints of nausea and vomiting at 0 h, 2 h, 4 h, 6 h, 12 h and 24 h, postoperatively. Rescue analgesic injection of diclofenac 75 mg intravenously was given if NRS > 4. Injection of ondansetron 8 mg intravenous was given for > 1 episode of vomiting.

The sample size was calculated using a software (Clincalc.com/stats/samplesize.aspx). In a previous study of Sarvestani et al. (2013), the total VAS score was 10.95 versus 12.95 in intraperitoneal hydrocortisone versus placebo; in reference to this, with 80% power and an alpha of 0.05, a minimum sample of 42 cases was required in each group. We decided to recruit 50 patients in each group.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad prism/QuickCalcs. The unpaired t-test and chi-square test were used to analyze the continuous and non-parametric data respectively. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Both groups were comparable in terms of patient demographic variables and duration of surgery (Table 1). The number of female patients (42 and 41) was higher than male patients (8 and 9) in each group showing no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05).

The difference between the severity of pain NRS score (mean ± SD) between the two groups is shown in Table 2. The mean NRS score was statistically significantly lower at 6, 12, and 24 h in the RD group compared to the RS group.

The requirement of rescue analgesia (diclofenac) was higher in group RS (76% of patients) compared to group RD (52% of patients) (Fig. 2). The difference between the two groups was statistically significant with a P value of 0.0004.

Time to first rescue analgesia requirement in group RD was longer (10.57 ± 7.83 h) than in group RS (7.56 ± 3.56 h) (P 0.0151) (Table 3), indicating better and longer pain relief in the RD group compared to the RS group.

Total analgesic consumption of diclofenac was also low in the RD group (87.5 ± 28.55 mg) than in the RS group (108.62 ± 47.37 mg). The difference between the two groups was very statistically significant with a P value of 0.0082 (Table 3).

Incidence of nausea and vomiting was significantly lower in the RD group than in the RS group (Table 4).

Discussion

Postoperative nausea and pain are the most common complications of laparoscopic surgery. The pain reaches a maximum level within 6 h of procedure and then gradually decreases over a couple of days but varies considerably between patients (Bisgaard et al. 2001; Jensen et al. 2007).

A number of techniques have been described for reducing post laparoscopy pain including intraperitoneal instillation of ropivacaine (Kang and Kim 2010), ropivacaine with nalbuphine (Singh et al. 2017), bupivacaine (Sharan et al. 2018), pre-incisional infiltration, and intraperitoneal instillation of levobupivacaine 0.25% (Louizos et al. 2005).

Bupivacaine is associated with cardiotoxicity when used in high concentration or when accidentally injected intravascularly. Ropivacaine is an S(−) enantiomer that is structurally related to bupivacaine and has less toxicity. Because of the lesser cardiotoxicity and less prolonged motor effect of ropivacaine, it was selected as a choice of drug for our study. Hence, in our study, we preferred ropivacaine over bupivacaine. Min Liang et al. (Liang et al. 2020) in their study compared the analgesic effect as well as the safety profile of laparoscopy-assisted wound infiltration with 0.75%, 0.5%, and 0.2% ropivacaine which provides equally strong analgesic effect. This is the first clinical study which disclosed that high concentration of ropivacaine is not necessary for infiltration, and dilution is preferred if large volume is needed. So, in our study, we used 0.2% ropivacaine with a total volume of 32 ml.

Administration of intraperitoneal local anesthetics alone (Khan et al. 2012; Beqiri et al. 2012) or in combination with nonopioid analgesics (Golubovic et al. 2009; Roberts et al. 2011) has been used to reduce postoperative pain following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. This might reduce adverse effects of opioids. On the other hand, steroids have also been used successfully for postoperative pain relief in different kind of surgeries (Choi et al. 2013; Buland et al. 2012). Glucocorticoids play a crucial role in regulating inflammatory responses by inhibiting the synthesis of bradykinin and other neuropeptides which are responsible for causing pain; based on this, we used dexamethasone with ropivacaine in our study.

The NRS score for abdominal pain was significantly less in group RD compared to group RS 6 h onwards till 24 h. A similar decrease in pain score was found by Evaristo-Méndez et al. (2013). In their study, they found that ropivacaine with dexamethasone for local infiltration decreased incisional pain intensity after 12 h post elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy with a good safety profile which is similar with our study. Our results are also in concordance with Park et al. (2011) and Cha et al. (2012). In contrary to our findings, Bisgaard et al. (1999) failed to show any decrease in visceral pain after intraperitoneal instillation of ropivacaine.

Sarvestani et al. (2013), in their study, showed that intraperitoneal injection of hydrocortisone before gas insufflation in laparoscopic cholecystectomy can reduce postoperative pain with no significant postoperative adverse effect. They also compared the frequency of nausea and vomiting and time of oral intake with saline group and found that they were similar in both groups which is different from our results.

Kumari et al. (2020) in their study of comparing the effect of intraperitoneal ropivacaine with or without tramadol in LC found that 90% in group R and 77.5% in group RT had nausea over the 24-h period. Combining nausea and nausea with retching, the incidence was 50% in group R and 32% in group RT in 1.5 h. One patient experienced vomiting in group R at 3 h. These values were not statistically significant (P > 0.05), while in our study, 12% and 10% patients in group RD compared to 26% and 20% patients in group RS experienced nausea and vomiting respectively which is statistically significant.

Conclusions

In our study, patients who received ropivacaine with dexamethasone had better pain relief and longer duration as compared to the patients who received ropivacaine with normal saline; also, patients in the dexamethasone group had less nausea and vomiting as compared to the patients in the saline group. Hence, we concluded that ropivacaine with dexamethasone when injected through the port gives more pain relief and is associated with less postoperative nausea vomiting which in turn leads to early mobilization and shorter hospital stay.

Limitations

The study needs to be done in larger sample to extrapolate the cost-effectiveness and validate the effect on pain and nausea vomiting.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used/analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- LC:

-

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy

- PONV:

-

Postoperative nausea and vomiting

- NRS:

-

Numeric rating scale

- NSAIDs:

-

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- LA:

-

Local anesthetic

- ASA:

-

American Society of Anesthesiology

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- C/I:

-

Contraindication

- O2:

-

Oxygen

- VAS:

-

Visual analog scale

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- NS :

-

Not significant

- SS:

-

Statistically significant

References

Beqiri AI, Domi RQ, Sula HH, Zaimi EQ, Petrela EY (2012) The combination of infiltrative bupivacaine with low-pressure laparoscopy reduces postcholecystectomy pain. A prospective randomized controlled study. Saudi Med J 33:134–138

Bisgaard T, Klarskov B, Kristiansen VB, Callesen T, Schulze S, Kelhet H et al (1999) Multi-regional local anesthetic infiltration during laparoscopic cholecystectomy in patients receiving prophylactic multi-modal analgesia: a randomized double-blinded, placebo-controlled study. Anesth Analg 89:1017

Bisgaard T, Klarskov B, Rosenberg J, Kehlet H (2001) Characterisics and prediction of early pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Pain 90:261–269

Buland K, Zahoor MU, Asghar A, Khan S, Zaid AY (2012) Efficacy of single dose perioperative intravenous steroid (dexamethasone) for postoperative pain relief in tonsillectomy patients. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 22:349–352

Cha SM, Kang H, Baek CW, Jung YH, Koo GH, Kim BG et al (2012) Peritrocal and intraperitonealropivacaine for laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective, randomized, double-blind controlled trial. J Surg Res 175(2):251–8

Choi YS, Shim JK, Song JW, Kim JC, Yoo YC, Kwak YL (2013) Combination of pregabalin and dexamethasone for postoperative pain and functional outcome in patients undergoing lumbar spinal surgery: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Clin J Pain 29(1):9–14

Chundrigar T, Hedges AR, Morris R, Stramatakis JD (1993) Intraperitoneal bupivacaine for effective pain relief after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 75(6):437–439

Dar FA, Najar MR, Jan N (2013) Effect of addition of dexamethasone to ropivacaine in supraclavicular brachial plexus block. Indian J Pain 27(3):165–169

Evaristo-Méndez G, de Alba-García JE, Sahagún-Flores JE, Ventura-Sauceda FA, Méndez-Ibarra JU, Sepúlveda-Castro RR (2013) Analgesic efficacy of the incisional infiltration of ropivacaine vs ropivacaine with dexamethasone in the elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Cir Cir 81(5):383–393

Golubovic S, Golubovic V, Cindric-stancin M, Tokmadzic VS (2009) Intraperitoneal analgesia for laparoscopic cholecystectomy: bupivacaine versus bupivacaine with tramadol. Coll Antropol 33:299–302

Jensen K, Khlet H, Lund CM (2007) Postoperative recovery profile after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective, observational study of a multimodal anaesthetic regime. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 51:464–471

Kang H, Kim BG (2010) Intraperitoneal ropivacaine for effective pain relief after laparoscopic appendectomy: a prospective, randomized, double blind, placebo- controlled study. J Int Med Res 38(3):821–832

Khan MR, Raza R, Zafar SN, Shamim F, Raza SA, Inam Pal KM et al (2012) Intraperitoneal lignocaine (lidocaine) versus bupivacaine after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Surg Res 178:662–669

Kumari A, Acharya B, Ghimire B, Shrestha A (2020) Post-operative analgesic effect of intraperitoneal ropivacaine with or without tramadol in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Indian J Anaesth 64:43–8

Kumhar G, Mayank A (2020) Comparative study of intraperitoneal instillation of levobupivacaine (0.25%) plus dexmedetomidine versus ropivacaine (0.25%) plus dexmedetomidine for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Eur J Mol Clin Med 7(8):3666–3672

Liang M, Chen Y, Zhu W, Zhou D (2020) Efficacy and safety of different doses of ropivacaine for laparoscopy assisted infiltration analgesia in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective randomized control trial. Medicine 99(46):e22540

Louizos AA, Hadzilia SJ, Leandros E, Kouroukli IK, Georgiou LG, Bramis JP (2005) Postoperative pain relief after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a placebo-controlled double blind randomized trial of preincisional infiltration and intraperitoneal instillation of levobupivacaine 0.25%. Surg Endosc 19:1503–6

Parameswari A, Krishna B, Manickam A, Vakamudi M (2017) Analgesic efficacy of dexamethasone as an adjuvant to caudal bupivacaine for infraumbilical surgeries in children: a prospective randomized study. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol 33(4):509–513

Park YH, Kang H, Woo YC, Park SG, Baek CW, Jung YH et al (2011) The effect of intraperitonealropivacaine on pain after laparoscopic colectomy: a prospective randomized controlled trial. J Surg Res 171(1):94–100

Roberts KJ, Gilmour J, Pande R, Nightingale P, Tan LC, Khan S (2011) Efficacy of intraperitoneal local anaesthetic techniques during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc 25:3698–3705

Sarvestani AS, Amini S, Kalhor M, Roshanravan R, Mohammadi M, Lebaschi AH (2013) Intraperitoneal hydrocortisone for pain relief after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Saudi J Anaesth 7(1):14–17

Sharan R, Singh M, Kataria AP, Jyoti K, Jarewal V, Kadian R (2018) Intraperitoneal instillation of bupivacaine and ropivacaine for postoperative analgesia in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Anesth Essays Res 12(2):377–380

Singh S, Giri MK, Singh M, Giri NK (2017) A clinical comparative study of intraperitoneal instillation of ropivacaine alone or ropivacaine with nalbuphine for postoperative analgesia in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Anaesth Pain Intensive Care 21(3):335–339

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DJ and BV have analyzed, observed, and interpreted the patient data, and DJ and RW were major contributors in writing the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The above study was presented in front of institutional ethics committee, GCS Medical College, Hospital and Research Centre, and was approved with reference no. GCSMC/EC/Research project/APPROVE/2021/264 on 26 March 2021. Written and informed consent was taken from all the patients involved in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jadav, D., Wadhawa, R. & Vaishnav, B. Intraperitoneal ropivacaine with dexamethasone versus ropivacaine alone for pain relief after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a randomized prospective trial. Ain-Shams J Anesthesiol 15, 71 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42077-023-00366-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42077-023-00366-y