Abstract

Background

There are few case reports in which non-cardiac surgery under regional anesthesia has been described in a patient with a pulmonary artery aneurysm. We report a case in which we managed a 74-year-old lady with a hip fracture for fixation under spinal anesthesia after thorough evaluation and meticulous planning. The patient was discharged home after 5 days without any perioperative events.

Case presentation

A 74-year-old, hypertensive lady with an incidentally detected pulmonary artery aneurysm was posted for a dynamic hip screw. Two-dimensional echocardiography revealed normal biventricular function with an ejection fraction of 60%, no regional wall motion abnormalities, concentric right ventricular hypertrophy (tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion or TAPSE of 19 mm), severe calcific pulmonary stenosis (PS) with pressures 90/61 mm Hg, pulmonary valve annulus of 12 mm, and pulmonary artery systolic pressure of 35 mm Hg. The left and right pulmonary artery diameters were 17 mm and 20 mm, respectively. She was clinically asymptomatic with an oxygen saturation of 98% on room air. A sequential lumbar epidural anesthesia was planned for this patient given her age, overall frail condition, and to avoid airway instrumentation. As epidural was difficult due to fused spaces, a sub-arachnoid block was administered with continuous monitoring. Surgery was uneventful and the patient was discharged on the 5th postoperative day.

Conclusions

With this case report, we suggest that a central neuraxial blockade could be administered in presence of severe PS with meticulous monitoring and careful planning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pulmonary artery aneurysms (PAA) are rare abnormalities but could be potentially catastrophic if it gets ruptured. Sudden rupture could lead to death due to hemorrhage, aspiration, and asphyxia. The presenting symptoms could be hemoptysis, shortness of breath, chest pain, palpitations, or syncopal episodes (Sk and Shaikh 2014; Kreibich et al. 2015). Presence of pulmonary stenosis (PS) also poses challenges in anesthetic management in presence of PAA. PS increases intraventricular pressure and work of the right ventricle and affects left ventricular output due to pushing of the interventricular septum to the left. Anesthetic goals should be to maintain adequate right ventricular preload, avoid a decrease in systemic and pulmonary vascular resistance, and maintain normal sinus rhythm (Sk and Shaikh 2014). We report a case in which we managed a 74-year-old lady with a hip fracture for fixation under spinal anesthesia after thorough evaluation and meticulous planning. The patient was discharged home after 5 days without any perioperative events.

Case presentation

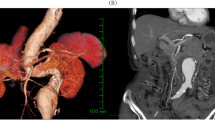

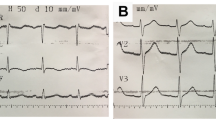

A 74-year-old lady, known hypertensive on lisinopril 10 mg and hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg sustained a fracture left hip due to a fall at home. She was reasonably active for her age with no history of dyspnea, productive cough, or chest pain. She was scheduled for a dynamic hip screw by the orthopedic team. Routine investigations (hemogram, renal function tests, coagulation profile) were unremarkable except for a right bundle branch block on the electrocardiogram. Chest radiograph revealed an ill-defined opacity around the left peri-hilar region. An echocardiogram was requested which revealed normal biventricular function with an ejection fraction of 60%, no regional wall motion abnormalities, concentric right ventricular hypertrophy (tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion or TAPSE of 19 mm), severe calcific pulmonary stenosis (PS) with pressures 90/61 mm Hg, pulmonary valve annulus of 12 mm, pulmonary artery systolic pressure of 35 mm Hg. The left and right pulmonary artery diameters were 17 mm and 20 mm, respectively. There were no intracardiac mass, thrombus, or pericardial effusion on echocardiography. As she was clinically asymptomatic and given the chest radiograph findings, the cardiologist advised a contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest which revealed aneurysmal dilatation of the main pulmonary trunk (52.2 mm in diameter), dilated right and left pulmonary arteries with no evidence of pulmonary embolism in the main branches. On further inquiry, the patient denied a history of any hemoptysis or connective tissue disorders to date. The cardiologist added 2.5 mg bisoprolol twice daily and the patient was accepted for dynamic hip screw under high-risk consent (Fig. 1).

A Chest radiograph PA view showing left perihilar opacity raising concerns (red arrow). B Axial view in chest CT showing dilated main pulmonary artery, right pulmonary artery, and ascending aorta. C Sagittal view in chest CT showing aneurysmal dilatation of main pulmonary artery. D Volume rendering technique CT showing aneurysmal dilatation of the main pulmonary artery

After shifting her to the operating room, two 18 G peripheral lines were secured and an arterial line was placed under local anesthesia. Monitoring included pulse-oximetry, cardio scope (lead 2, V5), and arterial blood pressure monitoring. Her baseline heart rate was 70 beats/min, blood pressure of 150/90 mm Hg, and oxygen saturation of 98% on room air with no dyspnea or tachypnea. A sequential lumbar epidural anesthesia was planned for this patient given her age, overall frail condition, and to avoid airway instrumentation. However, it was impossible to locate the epidural space due to the fused vertebra. We, therefore, co-loaded the patient with 250 ml crystalloid (Ringer lactate) and performed a subarachnoid block in L3–4 interspace under strict aseptic precautions using a 25G Quincke needle, and injected 7.5 mg of hyperbaric bupivacaine after confirming free flow of cerebrospinal fluid. Surgery was started after 20 min when an adequate level was achieved (T10). Surgery was accomplished uneventfully over 60 min with no hemodynamic changes with no requirement of vasoactive drugs (phenylephrine). One gram of paracetamol was infused intravenously during skin closure. Postoperatively she received oral tramadol 50 mg 8th hourly and paracetamol 1 g 8th hourly and also continued her antihypertensives along with 40 mg enoxaparin subcutaneously once daily for thromboprophylaxis. She had an uneventful course in the hospital and was discharged on the 5th postoperative day.

The patient has given consent for the images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patient understands that the name and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal the identity.

Discussion

The mean diameter of the pulmonary artery is 25 mm + / − 3 mm. A mean diameter of more than 40 mm is considered a pulmonary artery aneurysm (PAA). A true aneurysm involves all the layers of the vessel and is therefore compliant. On the other hand, a pseudoaneurysm does not involve all three layers and is therefore risky with a higher tendency to rupture. The incidence of PAA is very rare (1 in 14,000) and occurs due to various causes like vasculitis, congenital heart disease (patent ductus arteriosus, atrial and ventricular septal defects, pulmonary stenosis, bicuspid aortic valve), connective tissue disorders (Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Marfan syndrome, cystic medial necrosis), malignancy (lung cancer or pulmonary metastasis), post thoracic surgery, chronic pulmonary embolism, Behçet disease, and infection (tuberculosis, syphilis, endocarditis). It is usually detected incidentally during imaging for some other indications. In symptomatic patients, it could manifest as cough, dyspnea, hemoptysis, angina (due to pressure over the coronaries), airway compression, and pulmonary artery dissection (Gupta et al. 2020; Park et al. 2018; Theodoropoulos et al. 2013).

Medical management is offered when the patient is asymptomatic with mild to moderate pulmonary artery pressures. involves rate control (beta-blockers), statins, antiplatelets, and frequent imaging to monitor the size of the aneurysm. If the cause of PAA is established, the treatment can be initiated accordingly. Recommendations for surgical intervention are controversial, however, many experts advocate intervention for a PAA of more than 5.5 cm (Park et al. 2018).

This patient had severe calcific pulmonary stenosis which was responsible for right ventricular hypertrophy. There could be impaired left ventricular output due to pushing of the interventricular septum to the left. Therefore, cardiac output is maintained by systemic vascular resistance. A judicious preloading is essential to maintain right ventricular filling pressure but excessive fluids could precipitate right heart failure. The goal of the anesthetic technique is to optimize right ventricular preload, avoid an increase in pulmonary vascular resistance and decrease in systemic vascular resistance, maintain normal sinus rhythm, and maintain effective ventricular contractility (Shah et al. 2017; Sanikop et al. 2012).

We had planned lumbar epidural anesthesia which was technically difficult. We, therefore, administered a low-volume spinal anesthesia with cautious co-loading, monitoring rhythm abnormalities, and hemodynamics. Intraoperatively she received oxygen at 5 L/min via face mask as oxygen is a pulmonary vasodilator. She was advised to visit a higher center subsequently to follow up on her further management of PAA.

Conclusions

With this case report, we suggest that a central neuraxial blockade could be administered in presence of severe PS with meticulous monitoring and careful planning.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- PAA:

-

Pulmonary artery aneurysm

- PS:

-

Pulmonary stenosis

- TAPSE:

-

Tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion

References

Gupta M, Agrawal A, Iakovou A, Cohen S, Shah R, Talwar A (2020) Pulmonary artery aneurysm: a review. Pulm Circ 10:2045894020908780

Kreibich M, Siepe M, Kroll J, Höhn R, Grohmann J, Beyersdorf F (2015) Aneurysms of the pulmonary artery. Circulation 131:310–316

Park HS, Chamarthy MR, Lamus D, Saboo SS, Sutphin PD, Kalva SP (2018) Pulmonary artery aneurysms: diagnosis & endovascular therapy. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 8:350–361

Sanikop CS, Umarani VS, Ashwini G (2012) Anaesthetic management of a patient with isolated pulmonary stenosis posted for caesarean section. Indian J Anaesth 56:66–68

Shah RB, Butala BP, Parikh GP (2017) Anesthetic management of a parturient with severe pulmonary restenosis posted for cesarean section. Anesth Essays Res 11:517–519

Sushma KS, Shaikh S (2014) Anaesthetic management of pulmonary stenosis already treated with pulmonary balloon valvuloplasty. J Clin Diagn Res 8:193–4

Theodoropoulos P, Ziganshin BA, Tranquilli M, Elefteriades JA (2013) Pulmonary artery aneurysms: four case reports and literature review. Int J Angiol 22:143–148

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BS—this author helped in concepts, design, and manuscript preparation: MAA—this author helped in the definition of intellectual content, literature review, and manuscript editing: LJ—this author helped in definition of intellectual content and literature review: AY—this author helped in concepts, design, and literature review: AN—this author helped in concepts, design, definition of intellectual content, literature review, and manuscript review. The authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval—not applicable. Written informed consent was obtained to participate from the participant.

Consent for publication

Consent to publication has been taken. Written informed consent was obtained from the participant.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shanker, B., Alwardi, M.A., Jagani, L. et al. Perioperative management of a patient with incidentally detected pulmonary artery aneurysm undergoing non-cardiac surgery—a case report. Ain-Shams J Anesthesiol 15, 11 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42077-023-00306-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42077-023-00306-w