Abstract

Background

This randomized, double-blind study was designed to compare between sequential combined spinal epidural anesthesia versus epidural volume extension in lower limb surgery as regards hemodynamics, sensory, and motor blocks.

Methods

In this randomized, double-blind, prospective study, 80 patients scheduled for lower limb surgery were divided into two groups: sequential combined spinal epidural (SCSE) group in which small doses of local anesthetic was injected in epidural space after low-dose spinal anesthesia and epidural volume extension (EVE) group in which 10 ml saline was injected in epidural space after low-dose spinal anesthesia. Hemodynamics, anesthesia readiness time, degree of motor block, time to regression of sensory block, and side effects were measured.

Results

Hemodynamic changes were insignificant. Anesthesia readiness time was significantly faster in EVE group. Motor block and sensory block were better in SCSE. Postoperative bupivacaine consumption was statistically insignificant between the two groups.

Conclusion

Both SCSE and EVE techniques can preserve hemodynamics after low-dose subarachnoid block and can be used in high-risk elderly patients undergoing orthopedic surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Combined spinal epidural (CSE) is popular in modern anesthesia practice (Dureja et al., 2000). It provides rapid onset, prolonged duration, less incidence of toxicity from local anesthetics, and postoperative analgesia (Holmstrom et al., 1993). Geriatric patients undergoing major orthopedic surgery are much more at risk than younger ones due to less cardiorespiratory reserve and other comorbidities (Bernstein & Rosenberg, 1993).

Spinal anesthesia is a simple and quick technique, but it has a risk of severe hypotension. Sequential combined spinal epidural (SCSE) is a modified method of anesthesia in which a small spinal dose inadequate for surgery is used in an attempt to decrease incidence of hypotension and the block is then extended cephalad with the epidural drug (Hamdani et al., 2002). This technique is becoming famous in obstetric anesthesia practice but also can be used in patients undergoing orthopedic surgery due to hemodynamic stability (Bhattacharya et al., 2007a).

Epidural volume extension (EVE) is another modified method of CSE. This approach includes the use of normal saline into the epidural space immediately after intrathecal injection of the local anesthetic. The widely accepted mechanism of action is thecal compression of the subarachnoid space due to volume effect, which promotes cephalad displacement of local anesthetic in the cerebrospinal fluid (Stienstra et al., 1999).

The aim of this study is to compare between sequential combined spinal epidural anesthesia versus epidural volume extension in lower limb surgery as regards hemodynamics, sensory, and motor blocks.

Patient and methods

This prospective, double-blinded, randomized, parallel group study enrolled 80 patients ASA class I or II aged 21–60 years old who were scheduled for lower limb surgery in Ain Shams University Hospitals in Cairo, Egypt. The current study was approved by the local ethics committee. All the patients gave written consent. Exclusion criteria were ASA class ≥ III, contraindications to regional anesthesia (including coagulopathy and infection at the injection site) history of chronic use of opioids, body mass index (BMI) ≥ 35, uncooperative patients, and patients with known allergy to local anesthetics, opioids, NSAIDs or paracetamol.

On arrival in the operating room, standard monitoring was applied with automated noninvasive blood pressure measurement, ECG, and pulse oximetry. Baseline mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) and heart rate (HR) were recorded. Intravenous line G 18 was inserted in all patients and an infusion of 500 ml Ringer’s solution was started with monitoring of heart rate and blood pressure. The regional anesthesia was performed with the patient in the right lateral position at the fourth lumbar interspace using a midline approach. Patients were randomly assigned by a computer-generated list of random numbers using opaque, sealed envelopes to two groups.

Sequential combined spinal epidural (SCSE) group

Epidural space was identified with Tuohy 17-G needle using a loss of resistance to saline technique. Dural puncture using a 25-G Whitacre needle through the Tuohy needle and free flow of CSF was observed, 2 ml (10 mg) of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine over 30 s was administered into the subarachnoid space. All epidural catheters (19 G) were inserted 4 to 5 cm into the epidural space. Patients were then placed in a supine position immediately after fixing the epidural catheter in position. If the desired spinal level of T10 was not achieved after 10 min of subarachnoid block, then incremental epidural top-up dose with isobaric 0.5% bupivacaine 2 ml for every unblocked segment was given through epidural catheter till T10 level was reached. Intraoperative if spinal level receded to T12 level; then again, incremental epidural top-up with isobaric 0.5% bupivacaine was given to maintain sensory block at T10 level.

Epidural volume extension (EVE) group

Epidural space was identified with a 17-G Tuohy epidural needle using a loss of resistance to saline technique. Dural puncture using a 25-G Whitacre needle through the Tuohy needle and free flow of CSF was observed. Ten milligrams heavy bupivacaine was given in the subarachnoid space. Epidural catheters (19 G) were inserted 4 to 5 cm into the epidural space. Then, 10 ml saline was directly injected in the epidural space.

Sensory block was assessed by pin prick method on the operated limb side. Dermatome level tested every 5 min till 20 min. At the end of 20 min if the sensory block failed to reach T10 level or if patient had pain due to inadequate block, it was considered as failed block and general anesthesia was given and these patients were excluded from the study.

We recorded various variables like as follows:

Anesthesia readiness time as time from the end of injection of drug to the time sensory block reached T10 level.

Degree of motor block on operated limb was evaluated using a modified Bromage scale when patient with anesthesia was ready for surgery (Bromage 0: free movement of limb at hip, knee, and ankle joint. Bromage 1: free movement of limb at knee and ankle joint. Bromage 2: free movement of limb at ankle joint. Bromage 3: no movement of limb at hip, knee, and ankle joint). Duration of motor block noted as time from the onset of grade 3 motor block to complete resolution of motor block.

Time to regression of sensory block to T12 noted as time from the onset of T10 sensory block to regression of sensory level to T12. If due to regression of spinal block and inability to maintain surgical anesthesia during surgery in any group and if general anesthesia was supplemented intraoperative, then it was noted as supplementation of general anesthesia. Initial and total dose bupivacaine required to establish and maintain block to T10 level also noted down.

Hemodynamic variables such as systolic arterial blood pressure and heart rate before administering anesthesia and throughout the intraoperative period. Clinically significant hypotension was defined as decrease in systolic arterial pressure by 30% or more from baseline values or < 90 mm Hg. It was treated with IV ephedrine 5 mg incremental bolus dosages, and number of patients who needed ephedrine was noted. Clinically significant bradycardia was defined as a heart rate less than 50 beats per min, and it was treated with IV atropine 0.5 mg boluses. Incidences of clinically significant hypotension and bradycardia were noted as incidence of hemodynamic adverse event.

After surgery, epidural catheter was kept in situ for pain relief. Time to demand first rescue analgesia after completion of surgery from the onset of T10 sensory level was noted as duration of analgesia. Rescue analgesia was provided by epidural 10 ml of 0.125% bupivacaine when visual analogue scale (VAS) > 3. Intravenous pethidine 25 mg was added if the patient was not satisfied.

Side effects such as nausea, vomiting, postdural puncture headache, and backache were recorded.

To ensure blinding of the procedure, an investigator unaware of patient group allocation was responsible for post-procedure data collection. All patients and their nurses were unaware of group allocation.

Statistical analysis

Sample size was calculated based on previous study to detect a sensory block difference of 2 dermatome levels with an expected SD within groups of 3 (Loubert et al., 2011). A sample size of 36 patients in each study group has a level of significance of 0.05 and a power of 0.8. We enrolled 80 patients to allow for an 18% dropout.

Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS version 20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The variables were presented as mean (SD) or median (range) for continuous data or frequency and percentage for ordinal data. Continuous variables were analyzed using independent Student’s t test or or Mann-Whitney U test. Ordinal data were analyzed using Chi-square test. P < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

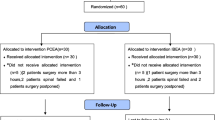

One hundred patients undergoing lower limb surgeries were identified. Twelve of them not meeting the inclusion criteria, eight refused to participate in the study, and the remaining 80 patients equally randomized to either EVE group (n = 40) or SCSE group (n = 40) (Fig. 1).

The demographic data of the two study groups were summarized in Table 1. Statistical analysis revealed non-significant differences between the two study groups as regards age, weight, height, gender, ASA physical status, and the duration of surgery.

Incidence of fall in heart rate or blood pressure showed no statistical significant difference between the two studied groups. Total ephedrine supplementation was also not significant between both groups (Table 2).

Anesthesia readiness time as time from the end of injection of drug to the time sensory block that reached T10 level was less significant in EVE group (18.4 min) compared in SCSE group (20.5 min); P value < 0.05 (Table 3). Modified Bromage scale when patient with anesthesia was ready for surgery was statistically significant greater in SCSE than in EVE group (Table 3).

Time to regression of sensory block to T12 noted as time from the onset of T10 sensory block to regression of sensory level to T12 was statistically significant between the two studied groups wherein the SCSE group (133.36 ± 15.35) is greater than the EVE group (120.43 ± 17.39) (Table 3).

Although a number of patients supplemented with general anesthesia were greater in the EVE group, i.e., 4 patients (11.1%), than in the SCSE group, i.e., 1 patient (2.5%), it was insignificant.

Time to the first request for postoperative analgesia was statistically significantly higher in SCSE group (230.47 ± 19.14) versus EVE group (190.54 ± 23.30); P value < 0.001 (Table 3). The number of patients and the total dose of pethidine required postoperatively was statistically insignificant between the two studied groups (Table 3).

Intraoperative total bupivacaine consumption was significantly higher in the SCSE group compared to that in the EVE group (P value < 0.001), while postoperative consumption was statistically insignificant between the two studied groups (Table 3).

There were no significant difference as regards the side effects such as nausea, vomiting, postdural puncture headache (PDPH), and backache between the two studied groups (Table 4).

Discussion

Epidural injection of small dose of local anesthetic or normal saline after low-dose spinal anesthesia was supposed to potentiate sensory and motor block (Terri et al., 2018). In this study, epidural volume extension with saline was compared to incremental small dose of local anesthetic after low-dose spinal anesthesia to evaluate hemodynamic variability in addition to readiness to start surgical incision in lower limb surgery.

Spinal anesthesia alone can produce hypotension despite of giving patients fluid preload and ephedrine especially in elderly people (Verring et al., 1991). To reduce the incidence of hypotension, a sequential combined spinal epidural technique in which a spinal dose of local anesthetic intended to be inadequate for surgery is used in an attempt to reduce hypotension. The block would be extended cephalad with the epidural drug. The onset of block is not delayed by this method, but at the same time, adequate level of sensory block is obtained (Thoren et al., 1994). This technique was used in obstetric anesthesia practice, but it can be used in orthopedic patients (Bhattacharya et al., 2007b). Many theories can explain how epidural top-up works after a spinal anesthesia in sequential CSEA. Leakage of epidural local anesthetic though the dural hole in the subarachnoid space and increasing pressure in the epidural space lead to squeezing of CSF to push the drug upward (Rawal et al., 2000).

Epidural volume expansion (EVE) was also another method to allow the dose of subarachnoid local anesthetic required for surgery to be reduced and consequently decrease the incidence of spinal block-associated hypotension (McNaught & Stocks, 2007). Early time (5 to 10 min) of saline injection in epidural space after spinal anesthesia is important for the success of the block (Mardirosoff et al., 1998).

Baricity of the drug and patient position in the subarachnoid space was crucial to help in drug spread upwards (Yamazaki et al., 2000), so block in the lateral decubitus position was done.

Anesthesia readiness was better in the EVE group due to the rapid extension of the local anesthetic in the subarachnoid space. Motor block time was lower in the EVE group, and this was similar to many studies in obstetric practice; with early regression of motor blockade after spinal anesthesia, two key components of enhanced recovery for cesarean delivery, early mobilization and catheter removal, are met (Lucas & Gough, 2013; Cohen et al., 1998). This leads also to decrease in the sensory time and time to first rescue analgesia. It might be an advantage if used in orthopedic surgery especially in day case surgeries such as knee arthroscopy.

Conclusion

Both SCSE and EVE techniques can preserve hemodynamics after low-dose subarachnoid block and can be used in elderly patients undergoing orthopedic surgery.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- EVE:

-

Epidural volume extension

- PDPH:

-

Postdural puncture headache

- SCSE:

-

Sequential combined spinal epidural

References

Bernstein RL, Rosenberg AD. The fractured hip. In: Manual orthopedic anesthesia and related pain syndromes. Churchill Livingstone 1993; 91-113.

Bhattacharya D, Tewari I, Chowdhuri S (2007a) Comparative study of sequential combined spinal epidural anesthesia versus spinal anesthesia in high risk geriatric patients for major orthopedic surgery. Indian Journal of Anesthesia. 51(1):32–36

Bhattacharya D, Tewari I, Chowdhuri S (2007b) Comparative study of sequential combined spinal epidural anesthesia versus spinal anesthesia in high risk geriatric patients for major orthopedic surgery. Indian J. Anaesth 51(1):32–36

Cohen SE, Hamilton CL, Riley ET et al (1998) Obstetric postanesthesia care unit stays: reevaluation of discharge criteria after regional anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 89(6):1559–1565

Dureja GP, Madan R, Kaul HL. Combined spinal epidural anaesthesia. In: Regional anaesthesia and pain management (current perspectives) B. I. Churchill Livingstone Pvt. Ltd., 2000; 139-145.

Hamdani GA, Chohan U, Zubair NA (2002) Clinical usefulness of sequential combined spinal epidural anesthesia in high risk geriatric patients for major orthopaedic surgery. J Anaesth Clin Pharmacol 18(2):163–166

Holmstrom E, Laugaland K, Rawal N et al (1993) Combined spinal epidural block versus spinal and epidural block for orthopedic surgery. Can J Anaesth 10(7):601–606

Loubert C, O’Brien PJ, Fernando R et al (2011) Epidural volume extension in combined spinal epidural anesthesia for elective caesarean section: a randomized controlled trial. Anesthesia 66:341–347

Lucas DN, Gough KL (2013) Enhanced recovery in obstetrics—a new frontier? Int J Obstet Anesth. 22(2):92–95

Mardirosoff C, Dumont L, Lemedioni P et al (1998) Sensory block extension during combined spinal and epidural. Reg Anesth Pain Med 23:92–95

McNaught AF, Stocks GM (2007) Epidural volume extension and low-dose sequential combined spinal-epidural blockade: two ways to reduce spinal dose requirement for caesarean section. International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia 16:346–353

Rawal N, Holmstrom B, Crohurst JA et al. The combined spinal epidural technique. In: Regional anaesthesia. Anesthesiology clinics of North America. W.B. Saunders Company 2000; (18)2: 267-295.

Stienstra R, Dilrosun-Alhadi BR, Dahan A et al (1999) The epidural ‘top-up’ in combined spinal-epidural anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 88(4):810–814

Terri K ,Tito D T, John K. Effect of epidural volume extension on quality of combined spinal-epidural anesthesia for cesarean delivery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AANA Journal 2018; April 86(2):109-118.

Thoren T, Holmstrom B, Rawal N et al (1994) Sequential combined spinal epidural block versus spinal block for caesarean section. Effects on maternal hypotension and neurobehavioral function of the newborn. Anesth Analg 78:1087–1092

Verring BT, Burmagl MD, Vletter AA et al (1991) The effect of age on systemic absorption and systemic disposition of bupivacaine after sub-arachnoid administration. Anesthesiology 74:250–257

Yamazaki Y, Mimura M, Hazama K et al (2000) Reinforcement of spinal anesthesia by epidural injection of saline: a comparison of hyperbaric and isobaric tetracaine. J Anesth 14:73–76

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all their colleagues in the orthopedic surgery department in Ain Shams University Hospital for their help in this research.

Funding

Nil.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KY has made the design of the work; the acquisition, analysis, interpretation of data, drafted the work and prepared the manuscript. The author has read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study has been approved by “Ain Shams University, Faculty of Medicine Research Ethics Committee” (REC) in May 2018. A written informed consent has been obtained from all patients enrolled in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Hakim, K.Y.K. Comparative study between sequential combined spinal epidural anesthesia versus epidural volume extension in lower limb surgery. Ain-Shams J Anesthesiol 12, 4 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42077-020-0055-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42077-020-0055-5