Abstract

Background

Sepsis is a common fatal complication of an infection. As part of the host response, sympathetic stimulation can result in many serious complications such as septic myocardial depression and metabolic, hematological, and immunological dysfunction. Treatment with beta blockers may reduce this pathophysiological response to infection, but the clinical outcomes are not clear.

Results

Our study showed a significant difference as regards decrease in heart rate in group B with P value < 0.001 compared to group A, besides a reduction in 28-day mortality (P value 0.0385) and ICU stay (P value < 0.001) in group B compared to group A.

Conclusion

This study supports the role of intravenous beta blockers in sepsis patients by decreasing heart rate without affecting the hemodynamics, in addition to decreasing 28-day mortality and ICU stay.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Sepsis is the leading cause to life-threatening organ failure due to non-organized host response to infection (Seymour et al. 2016). Septic shock is a severe sepsis with cardiovascular and metabolic/cellular affection, which has an increased mortality rate. Septic shock can be diagnosed by a clinical evidence of sepsis with persisting hypotension that needs vasopressors to keep mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) more than or equal to 65 mmHg in addition to a serum lactate level more than 2 mmol/L not responding to proper volume resuscitation. This raises the hospital mortality to be more than 40% (Shankar-Hari et al. 2016).

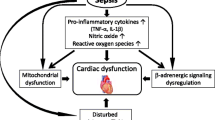

During infection, the attacking pathogens interact with the patient’s immune system initiating a downstream inflammatory sequence including the release of cytokines and other mediators that in turn produce a generalized systemic response which includes activation of sympathetic nervous system activation and release of catecholamines stimulating beta adrenergic receptors in the heart increasing contractility, heart rate, and cardiac output in order to cope with the high metabolic demands needed to fight the infection (Favero et al. 2013).

However, this pathophysiological process can cause multi-organ failure, and further clinical deterioration occurs due to a global imbalance between systemic oxygen supply and demand. This imbalance is due to the excessive release of catecholamine that causes sepsis-induced myocardial dysfunction, decreasing left ventricular ejection fraction followed by vasodilation, altered vascular permeability, myocardial depression, and failure of the coagulation cascade (Kenney and Ganta 2014).

Beta blockers are mainly used to treat arrhythmias and to protect the ischemic heart from a second heart attack (myocardial infarction). Despite their wide use to treat hypertension, they are not the first choice for initial treatment of most patients any more (James et al. 2014).

Beta blockers could reduce the continuous sympathetic stimulation in septic shock and relieve its effects, improving the outcomes. They could alter the production of cytokines, improving the metabolic dysregulation by reducing protein catabolism and basal metabolic energy needs and inhibiting gluconeogenesis.

On the contrary, using beta blockers in sepsis has the possibility to be hazardous. Many patients with septic shock are treated by beta agonists as vasopressor and inotrope infusions so they could exacerbate hypotension and bradycardia exacerbating shock in these patients (Sanfilippo et al. 2015).

Aim of the study

Evaluate the efficacy and safety of the use of beta blockers in ICU patients with sepsis.

Methods

After approval of the research ethical committee and obtaining informed written consent from patients or their relatives, this prospective randomized controlled study was conducted. We enrolled 60 patients of age 18–60 years of both sexes and randomly divided them into 2 groups, 30 patients each. We enrolled patients diagnosed with septicemia with the following clinical evidence of infection upon ICU admission: the presence of polymorph nuclear cells in a normally sterile body fluid, culture or gram stain of blood, sputum, urine, or normally sterile body fluid positive for a pathogenic microorganism, focus of infection identified by visual inspection; patients with evidence of a systemic response to infection as defined by the presence of three or more of the following signs within the previous 24 h: fever > 38.0 °C or hypothermia < 36.0 °C, tachycardia, and tachypnea or the patient requires mechanical ventilation—leukocytosis or leukopenia; and patients with disease leading to sepsis with or without evidence of either organ dysfunction or septic shock. Our exclusion criteria included patients who are not septic, refused participation, are with contraindication to use beta blockers, are with multi-organ failure on admission, and are on inotropes such as adrenaline and dobutamine.

Study procedures

During the assessment, all enrolled patients or relatives were informed about the study objectives and protocol. On admission and on daily basis, the following data were recorded: mean arterial blood pressure (every 4 h), heart rate (every 4 h), central venous pressure (every 4 h), urinary output, and daily full laboratory investigations including complete blood count, kidney functions, liver functions, arterial blood gases (ABG) and chest X-ray, electrocardiogram (ECG), and echocardiography (on admission and when needed).

Patients were randomized by closed envelope method into 2 equal groups, each consisting of 30 patients namely group A (control) and group B (esmolol). In group A, patients received the standard of care for sepsis according to our hospital protocol (broad-spectrum antibiotics according to suspected focus, fluids to elevate CVP above 10 mmHg, vasopressors to keep MAP > 65 mmHg, pan-cultures). In group B, patients received the standard of care for sepsis in addition to esmolol intravenous infusion by starting dose of 0.05–0.2 mg/kg/min and the dose was titrated every 20 min. Decreasing heart rate below 55 with hypotension MAP < 65 despite the measure to maintain them requires stopping of the esmolol infusion till reversal of the condition then restarted again.

The primary outcome was the heart rate. Secondary outcomes were MAP, central venous oxygen saturation measured from the central venous line, central venous pressure, serum lactate, APACHE II score (on admission), SOFA recorded daily for the first week beside ICU stays (in days), and 28-day mortality.

Sample size

Using the PASS program, the alpha error was set at 5% and power at 80%. Results from the previous study (Du et al. 2016) showed that the heart rate before and after the use of IV esmolol was 107.8 ± 8.7 and 86.2 ± 10.2, respectively, with P value 0.001. Based on this, the needed sample is 30 cases per group (60 total). The effect size was 2.27.

Statistical analysis

Data was analyzed. Statistical analysis was performed using computer software Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS, version 20; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data were expressed as mean values ± SD, numbers (%). Student’s t test was used to analyze the parametric data, and discrete (categorical) variables were analyzed using the χ2 test. Significance level (S) was set at a P value of 0.05 or less, and a P value of 0.01 or less was considered highly significant (HS).

Results

We enrolled 60 septic patients and randomly divided them into 2 groups: 30 patients in group A received the standard care of sepsis in addition to esmolol intravenous infusion by starting dose of 0.05–0.2 mg/kg/min and the dose was titrated every 20 min, and in group B, patients received the standard care of sepsis.

There was no significant difference between the two groups regarding age, sex (Table 1), and admission hemodynamic and inflammatory variables (Table 2), mean arterial pressure (Table 3 and Fig. 1), central venous pressure (Table 4 and Fig. 2), central venous oxygen saturation measured from the central venous line sample (Table 5 and Fig. 3), serum lactate (Table 6 and Fig. 4), and APACHE II score (Table 2) and SOFA score (Table 7 and Fig. 5) during the first week.

Heart rate showed a significant reduction in group B compared to group A in days 1–6 (P value < 0.001) (Table 8 and Fig. 6).

There was a significant reduction in ICU stay (Table 9 and Fig. 7) and 28-day mortality (Table 9 and Fig. 8) of group B compared to group A (P value 0.001 and 0.0385, respectively).

Discussion

This randomized controlled study was conducted on 60 ICU patients with sepsis divided into 2 groups to compare the effect of IV beta blockers on hemodynamics and ICU stay and mortality. The results showed a significant difference regarding heart rate reduction being evident in the IV beta blocker group, also reduction of mortality and ICU stay being the lowest in patients who received IV beta blockers.

Although the mortality from septic shock has fallen in recent years, this has been through improved detection and earlier antibiotic therapy. In our study, we hypothesized the benefits of BB in patients with sepsis such as significant lowering in HR, ICU stay, and 28-day mortality.

There is a question of whether beta blockers could offer a way of treating the critically ill patient with septic shock? And if so, how its benefits may arise? Could it be due to that adrenergic system is a powerful stimulator of the immune system? (Elenkov et al. 2000).

Although there has been a great deal of focus on the cardiovascular benefits of beta blockade in sepsis, the ubiquitous nature of the adrenergic system brings Cohen et al. (2004) to question whether there are other mechanisms through which beta blockers may exert their influence (Rudiger 2010).

A single-center phase II study from Italy showed results that agree with ours by Morelli et al. (2013) who randomly assigned 77 patients to be treated by esmolol continuous infusion titrated to keep the heart rate between 80/min and 94/min for the duration of ICU stay and 77 patients are subjected to standard treatment. The results reported that beta-adrenergic blockade in patients who continued to have high heart rates after standard fluid resuscitation caused improvements in cardiovascular performance including heart rate, left ventricle stroke volume, and systemic vascular resistance index; serum lactate; and a decrease in vasopressor dependence, with no adverse effects (Morelli et al. 2013).

Agreeing with our results is a secondary analysis of a prospective observational single-center trial by Fuchs et al. (2017) who compared mortality rates between adult patients with severe sepsis or septic shock, in whom chronic beta blocker therapy was continued and discontinued, respectively. A total of 296 patients with severe sepsis or septic shock and on chronic oral beta blocker were included. Chronic beta blocker was stopped during the acute phase of sepsis in 129 patients and continued in 167 patients. Continuation of beta blocker was associated with a decreased hospital, 28-day, and 90-day mortality rates in contrast to their discontinuation (Fuchs et al. 2017).

Also in the side of our results, Fuchs et al. (2015) performed an observational, single-center cohort study of intensive care unit (ICU) patients with primary severe sepsis or septic shock. They included 580 adult patients. Cessation of a pre-existing treatment with beta blockers during sepsis therapy was attributed to increased 90-day mortality of 71% compared to 42% in patients with ongoing therapy (P < 0.001). In contrast, newly started oral beta blockers decreased the 90-day mortality from 42% in patients without beta blocker therapy before and during sepsis to 28% (P < 0.05). They concluded that chronic beta blocker therapy should continue in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. In addition, the newly started beta blocker therapy should be considered in septic patients after stabilization (Fuchs et al. 2015).

Balik et al. (2012) enrolled ten septic patients who were given esmolol drip. The heart rate decreased from mean 142 ± 11/min to 112 ± 9/min (P < 0.001) with parallel insignificant reduction of the cardiac index. Twenty-eight-day mortality was 10% (1/10) (Balik et al. 2012).

Du et al. (2016) recruited 63 septic shock patients from the intensive care unit of Peking Union Medical College Hospital. After starting esmolol therapy, blood pressure was not altered, whereas stroke volume (SV) improved compared with that before esmolol therapy (P = 0.047), and lactate levels (P = 0.015) were also reduced after esmolol therapy (Du et al. 2016).

Agreeing with our results, Shang et al. (2016) conducted a randomized control study of 151 patients with severe sepsis who were enrolled and divided into the esmolol group (n = 75) and the control group (n = 76) that were treated by standard antiseptic shock measures. The esmolol group was treated by continuous IV infusion of esmolol. The results showed that esmolol reduced heart rates and the duration of mechanical ventilation in patients with severe sepsis, with no hazardous effect on circulatory function or perfusion (Shang et al. 2016).

Lee et al. (2019) and Li et al. (2020) both systematic review showed results agreeing with our results, decreasing both heart rate and mortality in patients receiving beta.

On the contrary, Al Harbi et al. (2018) conducted a nested cohort study in which all medical-surgical ICU patients (N = 523) were grouped according to β-blocker use during ICU stay. The primary endpoints were all-cause ICU and hospital mortality. Their results showed that 89 (17.0%) were treated by β-blockers during their ICU stay. There was no significant attribution between β-blocker therapy and ICU mortality (P = 0.16), hospital mortality (P = 0.73), or ICU length of stay (P = 0.22). However, β-blocker use was related to the increase in ICU and hospital mortality among non-diabetic patients. This controversy could be associated due to the exclusion of type I diabetes, diabetic ketoacidosis, pregnancy, “do-not-resuscitate” status within 24 h of admission, terminal illness, admission to the ICU after cardiac arrest, seizures, liver transplantation, and/or burn injury (Al Harbi et al. 2018).

Conclusion

We concluded that beta blocker use in ICU septic patients decreased heart rate, ICU stay, and 28-day mortality.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ABG:

-

Arterial blood gases

- APACHE II:

-

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation

- CVP:

-

Central venous pressure

- HR:

-

Heart rate

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- MAP:

-

Mean arterial pressure

- RBS :

-

Random blood sugar

- ScvO2 %:

-

Saturation central venous oxygen

- SOFA:

-

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment Score

- SV:

-

Stroke volume

References

Al Harbi SA, Al Sulaiman KA, Tamim H, Al-Dorzi HM, Sadat M, Arabi Y (2018) Association between β-blocker use and mortality in critically ill patients: a nested cohort study. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol 19(1):22

Balik M, Rulisek J, Leden P, Zakharchenko M, Otahal M, Bartakova H, Korinek J (2012) Concomitant use of beta-1 adrenoreceptor blocker and norepinephrine in patients with septic shock. Wien Klin Wochenschr 124(15-16):552–556

Cohen MJ, Shankar R, Stevenson J, Fernandez R, Gamelli RL, Jones SB. Bone marrow norepinephrine mediates development of functionally different macrophages after thermal injury and sepsis. Annals of Surgery. 2004;240(1):132–141. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000130724.84914.d6.

Du W, Wang XT, Long Y, Liu DW (2016) Efficacy and safety of esmolol in treatment of patients with septic shock. Chin Med J 129(14):1658–1665

Elenkov IJ, Wilder RL, Chrousos GP, Vizi ES (2000) The sympathetic nerve--an integrative interface between two supersystems: the brain and the immune system. Pharmacol Rev 52(4):595–638

Favero AM, Sordi R, Nardi G, Assreuy J (2013) Increased sympathetic tone contributes to cardiovascular dysfunction in sepsis. Critical Care 17(Suppl 4):P81

Fuchs C, Scheer C, Wauschkuhn S, Vollmer M, Rehberg S, Meissner K, Kuhn SO, Friesecke S, Abel P, Gründling M (2015) 90-day mortality of severe sepsis and septic shock is reduced by initiation of oral beta-blocker therapy and increased by discontinuation of a pre-existing beta-blocker treatment. Intensive Care Med Exp 3(Suppl 1):A88

Fuchs C, Wauschkuhn S, Scheer C, Vollmer M, Meissner K, Kuhn SO, Hahnenkamp K, Morelli A, Gründling M, Rehberg S (2017) Continuing chronic beta-blockade in the acute phase of severe sepsis and septic shock is associated with decreased mortality rates up to 90 days. Br J Anaesth 119(4):616–625

James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL et al (2014) Evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 80). JAMA. 311(5):507–520

Kenney MJ, Ganta CK (2014) Autonomic nervous system and immune system interactions. Comprehensive Physiol 4(3):1177–1200

Lee YR, Seth MS, Soney D, Dai H (2019) Benefits of beta-blockade in sepsis and septic shock: a systematic review. Clin Drug Investig 39(5):429–440

Li J, Sun W, Guo Y, Ren Y, Li Y, Yang Z (2020) Prognosis of β-adrenergic blockade therapy on septic shock and sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Cytokine 126:154916

Morelli A, Ertmer C, Westphal M, Rehberg S, Kampmeier T, Ligges S, Orecchioni A, D'Egidio A, D'Ippoliti F, Raffone C, Venditti M, Guarracino F, Girardis M, Tritapepe L, Pietropaoli P, Mebazaa A, Singer M (2013) Effect of heart rate control with esmolol on hemodynamic and clinical outcomes in patients with septic shock: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 310(16):1683–1691

Rudiger A (2010) Beta-block the septic heart. Crit Care Med 38(10 Suppl):S608–S612

Sanfilippo F, Santonocito C, Morelli A et al (2015) Beta-blocker use in severe sepsis and septic shock: a systematic review. Curr Med Res Opin 31:1817–1825

Seymour CW, Liu V, Iwashyna TJ et al (2016) Assessment of clinical criteria for sepsis. JAMA. 315(8):762–774

Shang X, Wang K, Xu J, Gong S, Ye Y, Chen K, Lian F, Chen W, Yu R (2016) The effect of esmolol on tissue perfusion and clinical prognosis of patients with severe sepsis: a prospective cohort study. Biomed Res Int 2016:1038034

Shankar-Hari M, Phillips G, Levy ML et al (2016) Assessment of definition and clinical criteria for septic shock. JAMA. 315(8):775–787

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding source was declared.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RG and DI designed the study and revised the literature. HZ critically reviewed the manuscript. EA analyzed the data and wrote and critically revised the manuscript. MA followed up the patients, collected the data, performed the analysis, and wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approval of the research ethical committee of Faculty of Medicine, Ain-Shams University, was obtained (code number: FMASU MD (69/2018), approval date 28 February 2018), and written informed consent was obtained from patients and/or their first-degree relatives.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gadallah, R.R., Aboseif, E.M.K., Ibrahim, D.A. et al. Evaluation of the safety and efficacy of beta blockers in septic patients: a randomized control trial. Ain-Shams J Anesthesiol 12, 57 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42077-020-00107-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42077-020-00107-5