Abstract

Background

An encephalocele is a congenital neural tube defect characterized by herniation of cranial contents through a defect in the cranium and is caused by failure of the closure of the cranial part of the developing neural tube. An encephalocele is termed as “giant encephalocele” when the size of encephalocele is larger than the size of the head. They depend on size of the sac, percentage of neural tissue content, hydrocephalus, infection, and other associated pathologies for a favorable neurological outcome.

Case presentation

We report a case of a four-month-old boy with a giant occipital encephalocele measuring 21 × 15 × 19 cm in size, which was a surgical and anesthetic challenge for us. Intubation was achieved in lateral position. Part of occipital and cerebellar parenchyma was present in the sac and bony defect was approximately 2.5 cm in occipital bone in midline. We performed surgical excision and repair with a good overall outcome.

Conclusion

Perioperative management of a giant occipital encephalocele is a challenge for both anesthesiologists and neurosurgeons. Managing such a case demands a search for other congenital abnormalities, expertise in handling airway, and proper intraoperative care. Careful planning and perioperative management are essential for a successful outcome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Encephalocele is a rare neural tube defect, typically occurring in one per every 5,000 births worldwide, of which 70% are occipital [1]. It is classified by the herniation of multiple cranial contents in the initial weeks of fetal life, through a defect in the cranium caused by inappropriate closure of the developing cranial part of the neural tube [2]. The size of an encephalocele varies from a few centimeters to an enormous swelling and is termed as “giant encephalocele,” when the size of encephalocele is more substantial than the size of the head [2].

Such cerebral malformations are dependent on their size of the sac, percentage of neural tissue content, hydrocephalus, possible infections, and other associated pathologies for a favorable neurological outcome. Preoperative neurological status of the patients and the cranial contents herniating into the sac remain the vital factors in deciding the long-term prognosis. The anesthetic management of occipital meningoencephalocele presents a challenge due to apparent difficulty in satisfactorily establishing the airway while being in a prone position, blood loss, and perioperative care [3].

Case presentation

A 4-month-old baby boy presented to us through the pediatric emergency department following a fall from his mother's lap. This baby boy sustained a huge swelling on the back of his head since birth, and it increased in size over a period. There was no history of antenatal checkups and baby was delivered via cesarean section at term in a local hospital and was examined by a local pediatrician. He was not advised for any neurosurgical opinion and was discharged. The child referred to the neurosurgery department after a history of fall from his mother’s lap due to the presence of a challenging swelling on his head.

On examination, the child was active. He had a huge occipital swelling measuring about 21 × 15 × 19 cm in size (Fig. 1A, B). Swelling was cystic and transilluminates. The overlying skin was intact, though few areas of skin necrosis due to pressure were seen. No apparent traumatic injury observed. Anterior fontanelle was lax and open, measuring about 3.5 × 2.5 cm. The child was moving all four limbs and power and tone were normal. With the aforesaid clinical findings, a diagnosis of giant occipital encephalocele was established.

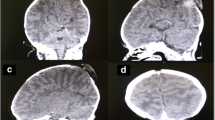

Routine investigations were normal. His magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain plain was done which reported a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) containing sac with the brain parenchymal tissue herniating through a defect in posterior occipital bones in midline. It measured approximately 21 × 15 × 19 cm. Bilateral lateral and third ventricles were normal. Consequently, it was concluded it to be a huge meningoencephalocele without hydrocephalus. (Fig. 2A, B).

Parents were counselled in detail about the diagnosis and after obtaining informed written consent, we proceeded to perform surgical excision and repair. It was a significant challenge for our anesthetist to intubate this child. Intubation was achieved in lateral position and was supervised in same position throughout. The surgical area was cleaned and draped while holding the encephalocele in hands. Incision was performed along the neck of the sac and deepened through skin layers. Dissection done layer by layer and excised the sac along with dysplastic brain tissue was excised. Part of occipital and cerebellar parenchyma was discovered in the sac. Dural venous sinuses were not involved. Dural layer was precisely identified, and brain tissue was reduced through a bony defect of 2.5 cm size in occipital bone in midline and closure done with coated Vicryl (polyglactin 910) 4-0 sutures. Valsalva maneuver performed and no CSF leak was noted. Subcuticular layer was closed with Vicryl (polyglactin 910) 3-0 sutures. Skin closure was done with Prolene (polypropylene) 3-0 sutures. The child had an uncomplicated extubation and started to feed 3 h after the surgery. There was minimal blood loss during the surgery, hence blood transfusion was not done. The baby didn't develop hydrocephalus and was discharged after 3 days.

Discussion

The meningeal membrane covering the giant encephalocele is either covered by a normal, dysplastic or a thin membrane. Clinically, the presentation of giant occipital encephaloceles is evident because of their characteristic swelling [2]. The contents of occipital encephalocele primarily include meninges and occipital lobes. It may also comprise of ventricles, cerebellum, and brain stem. The key factors influencing the outcome of patients with occipital encephalocele are site, size, and herniation of the brain into the sac. The presence of the brainstem or occipital lobe with or without the dural sinuses in the sac along with hydrocephalus also influences the outcome of the case [4].

The large-sized swellings may conceivably have a remarkable brain herniation, an abnormality of the underlying brain and microcephaly. The clinical examination incorporates the examination of its size, extent, amount of prominence, and its location along with the size of bony defect [2]. The size of the head holds a significant importance for clinical suspicion of microcephaly or hydrocephalus and extracranial anomalies [2]. MRI brain remains the usual investigation of choice along with the three-dimensional computed tomography (CT) that further helps in evaluating the deformity [5].

Giant encephaloceles are rare; surgical procedures represents a challenging task for the anesthesiologists, as well as the neurosurgeons. The challenges present are principally due to its complex site, enormous size, associated bulging contents resulting in intracranial anomalies, intraoperative blood loss, and prolonged anesthesia [6]. The supreme aim of the anesthesiologist is to prevent premature rupture of the encephalocele intraoperatively. The occipital site of the encephalocele causes a hindrance with the intubation as due to a difficult airway caused by the restriction of the neck movement. This further leads to an inability of having an optimal tracheal intubation position [3].

The operative procedure additionally includes the management of possible loss of copious quantities of CSF causing superimposed electrolyte imbalance. Infants with encephalocele can develop sudden hypothermia due to dysfunction of autonomic control below the present defect [3]. Thus, urgent consideration and management must be given to hypothermia, blood loss, and its associated complications. The surgery is advised to be done as promptly as possible to escape life threatening complications such as central nervous system (CNS) infections, respiratory distress, aspiration pneumonia, irreversible impairment of vagus nerve, and hypothermia [5].

The table below incorporates all the reported cases to the author's knowledge. (Table 1) [3, 4, 9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21] The key aim is to portray the different and most commonly used surgical procedures in the management of giant occipital encephaloceles. The most frequently used method is sheer resection and dural repair. Expansion cranioplasty is one of the surgical procedures that consists of a mesh to provide room for the protruded sac. Another technique commonly practiced is executed through ventricular volume reduction. It is a two-step technique which first increases the ventricular pressure inducing hydrocephalus followed by insertion of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt. The ventricles then contract, and the protruded tissue repositions itself inside the cranium. For the herniated cerebellar and occipital parenchyma, an incision is required in the tentorium to establish an infratentorial area for the herniated tissue to retract [7].

Modern-day neurosurgical techniques along with neuroimaging and neonatal intensive care with neurological facilities have markedly improved morbidity and mortality rate in the management of encephaloceles [8]. Postoperatively, complications such as hypothermia, raised intracranial pressure (ICP), apnea, cardiac arrest, CSF leak, and infection can arise and hence need to be managed effectively. However, in our case no complications were present. Alongside all present difficulties, intubation and anesthetic management in our patient were consistently achieved.

Conclusions:

Perioperative management of a giant occipital encephalocele is an extensive team challenge for both anesthesiologists and neurosurgeons. These patients encounter a difficulty in attaining the supine position. Endotracheal intubation is achieved in the lateral position. The prognosis is crucially dependent on the extent of the invasion of cranial contents into the sac. Because of the herniation of parts of the brain, there is a significant rise in the difficulty level of the surgical procedure. There is habitually a more remarked risk of infection involved in giant encephaloceles usually due to CSF leakage. To minimize superimposed complications, carrying out the operative procedure at a primitive age is immensely beneficial.

Availability of data and materials

All data are within the article.

Abbreviations

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

- ICP:

-

Intracranial pressure

References

Black SA, Galvez JA, Rehman MA, Schwartz AJ. Images in anesthesiology: airway management in an infant with a giant occipital encephalocele. Anesthesiology. 2014;120:1504.

Ghritlaharey RK. A brief review of giant occipital encephalocele. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2018;9(4):455–6.

Pahuja H, Deshmukh S, Palsodkar S, Lande S. Anaesthetic management of neonate with giant occipital Meningoencephalocele. Int J Res Med Sci. 2015;31:1. https://doi.org/10.5455/2320-6012.ijrms20150165.

Nath HD, Mahapatra AK, Borkar SA. A giant occipital encephalocele with spontaneous hemorrhage into the sac: a rare case report. Asian J Neurosurg. 2014;9(3):158–60.

Velho V, Naik H, Survashe P, Guthe S, Bhide A, Bhople L, Guha A. Management strategies of cranial encephaloceles: a neurosurgical challenge. Asian J Neurosurg. 2019;14:718–24.

Ganeriwal V, et al. Giant meningoencephalocele with Arnold-Chiari type III malformation and anaesthetic challenges: a rare case report. Saudi J Anaesthesia. 2019;13(2):136–9. https://doi.org/10.4103/sja.SJA_616_18.

Alwahab A, Kharsa A, Nugud A, Nugud S. Occipital Meningoencephalocele case report and review of current literature. Chin Neurosurg J. 2017;3(1):10.

Rehman L, Farooq G, Bukhari I. Neurosurgical interventions for occipital encephalocele. Asian J Neurosurg. 2018;13:233–7.

Naik V, Marulasiddappa V, Gowda Naveen MA, Pai SB, Bysani P, Amreesh SB. Giant encephalocoele: a rare case report and review of literature. Asian J Neurosurg. 2019;14(1):289–91.

Antunes M, Pizzol D, Calgaro S, Di Gennaro F, Colangelo A. Case report Giant Encephalocele: successful management in limited-resource settings. EuroMediterranean Biomed J. 2019;14:114–6. https://doi.org/10.3269/1970-5492.2019.14.26.

Bulut M, Yavuz A, Bora A, Gülşen İ, Özkaçmaz S, Sösüncü E. Chiari III Malformation with a Giant Encephalocele Sac: case report and a review of the literature. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2013;49(5):316–9.

Agarwal A, Chandak AV, Kakani A, Reddy S. A giant occipital encephalocele. APSP J Case Rep. 2010;1(2):16.

Kumar V, Kulwant SB, Saurabh S, Chauhan R. Giant occipital meningoencephalocele in a neonate: a therapeutic challenge. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2017;12:46. https://doi.org/10.4103/1817-1745.205655.

Murthy PS, Kalinayakanahalli Ramkrishnappa SK. Giant occipital encephalocele in an infant: a surgical challenge. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2019;14(4):218–21.

Agrawal AC, Umamaheshwara RV, Hegde KV, Suneetha P, Kolikipudi DS. Giant high occipital encephalocele. Romanian. Neurosurgery. 2016;30:122–6.

Kaif D, Ahmad D, Kumar Singh D, Pandey D. Giant occipital encephalocele – a report of two rare cases. J Med Sci Clin Res. 2017;05(02):18162–5.

Dasgupta S, Saha S, Baranwal S, Banga M, Sandeep B. A rare case of giant occipital encephalocele with craniosynostosis. Asian J Med Sci. 2016;7(4):98–100.

Mahapatra AK. Giant encephalocele: a study of 14 patients. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2011;47:406–11.

Mahajan C, Rath GP, Bithal PK, Mahapatra AK. Perioperative management of children with giant encephalocele: a clinical report of 29 cases. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2017;29(3):322–9.

Ozdemir N, Ozdemir SA, Ozer EA. Management of the giant occipital encephaloceles in the neonates. Early Hum Dev. 2016;103:229–34.

Kanesen D, et al. Giant occipital encephalocele with Chiari malformation type 3. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2018;9(4):619–21.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was required for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SZ and AK wrote the manuscript. AK is involved in the surgical management of the patient. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was taken from the mother of the child for publication of case report and accompanying images.

Competing interests

None of the authors has any conflict of interest to disclose. We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this case report is consistent with those guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zahid, S., Khizar, A. Giant occipital encephalocele: a case report, surgical and anesthetic challenge and review of literature. Egypt J Neurosurg 36, 38 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41984-021-00136-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41984-021-00136-8