Abstract

Background

Migraine is one of the most disabling disorders worldwide. Globally, in 2019, headache disorders were the cause of 46.6 million years of disability, with migraine accounting for 88.2% of these. The value of integrative strategies in migraine management has been raised due to the recurrent and provoked nature of migraine. So, the current study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of implementing a therapeutic patient education and relaxation training program versus usual pharmacological treatment alone on the frequency, severity, and duration of migraine attacks as the primary outcome and migraine-related disability and quality of life as the secondary outcome. A randomized controlled trial was conducted at the specialized headache clinic of a tertiary referral center. Sixty patients were randomly assigned to intervention or control groups. Participants in the intervention arm received the education and relaxation training program and were instructed to perform daily relaxation exercises in addition to their routine pharmacological treatment, whereas the control group only received their routine treatments. Follow-up was done after 1 and 3 months using a headache diary and a migraine-specific quality of life questionnaire (MSQ).

Result

After implementation of the program, there was a significant reduction in migraine attack severity in the intervention group compared to the control group, and they also had significantly fewer migraine headache days/month and duration of migraine attacks compared to patients in the control group. Statistically significant improvement in the role-function restrictive, role-function preventive, and emotional function domains of MSQ.

Conclusion

An integrated migraine management program has a significant effect on reducing the burden of migraine attacks and improving the daily activities of migraine sufferers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Migraine is the most widespread and disabling multifactorial chronic neurological disorder [1]. It was described as recurrent episodes of moderate to severe pulsating head pain that can be unilateral or bilateral, exacerbated by routine physical activity, and can last for 4 to 72 h [2, 3]. Migraine has a significant impact on patients’ daily routine living activities [4, 5]. According to a 2019 Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study, headache disorders were the second leading cause of years lived with disability (YLD), following backache, with 88.2% of these attributable to migraine [6].

Therapeutic patient education (TPE) is a patient-centered approach integrated into health care through trained health care workers aiming to engage patients in their self-management behaviors to achieve the best possible quality of life (QOL). It has shown efficacy in the management of various chronic disorders, such as asthma, diabetes, psychiatric diseases, and obesity [7, 8]. Migraine patient education has been reported to be an essential component of migraine care [9,10,11]. Evidence collected during the COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated that lifestyle changes can be used to manage migraines [12].

Progressive muscle relaxation (PMR) is a level A evidence as one of the modalities of relaxation techniques in migraine management [13]. It consists of muscle tension-reducing techniques with the aim of achieving profound relaxation and relieving any tension and anxiety [14, 15].

Recent studies concluded that a multidisciplinary integrative strategy in migraine management combining therapeutic patient education, pharmacological, and behavioral therapy has proven to be the best way to minimize headache frequency and intensity, improve patients’ quality of life [16,17,18], and maximize the efficacy of pharmacological treatment [12, 19].

Although there is evidence for the effectiveness of TPE and PMR on migraine management, there is a poor and limited literature in the Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR), particularly Egypt. The purpose of this intervention study was to evaluate the effectiveness of an integrated therapeutic patient education and relaxation training program on migraine attack severity, frequency, duration, and patients’ QOL versus routine pharmacological treatment alone among adult patients attending the headache clinic at a tertiary referral center.

Methods

A randomized, single-blind controlled trial was conducted at the specialized headache outpatient clinic of a tertiary referral center from February 2020 to September 2021.

The study populations were all patients who attended the specialized headache clinic and were diagnosed with migraine headaches by the headache specialist-neurologist according to diagnostic criteria set by the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-III) [20]. The inclusion criteria were patients aged 18–65 years old, diagnosed with migraine for at least 6 months, experiencing 4 or more migraine days per month with disability affecting daily living activities, productivity, and quality of life, taking their prescribed medication by the headache specialist-neurologist (symptomatic and preventive), and reporting a constant pattern of migraine symptoms over the previous 3 months. Patients with major psychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety, and/or personality disorders were excluded using the Arabic version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) and Axis II Disorders (SCID-II) [21, 22] during the recruitment stage before randomization.

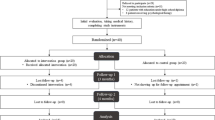

The eligible participants were randomly allocated using a concealment strategy; sealed opaque envelopes were used containing codes for intervention or control; the participants were assigned numbers based on the order of their visits. After signing the informed consent, participants were asked to pick one envelope from the box and hand it over to the researcher. Then the researcher assigned them to either the intervention or control group according to the envelope code.The three phases of the intervention were illustrated in (Fig. 1).

The sample size was calculated based on a study of the efficacy of psycho-educational groups and relaxation training by Elisa and Federica. 2016 [7] showed efficacy of more than 40% in reducing the frequency of attacks and improving QOL. Group sample sizes of 25 in the intervention group and 25 in the control group achieve 80% power to detect a difference between the group proportions of 35%. The proportion in the intervention group was assumed to be 85%, while in the control group it was 50%. Assuming a 20% dropout rate during the 3-month follow-up, we planned to enroll 30 patients in each of the control and intervention groups.

Regarding methods, a questionnaire was developed to collect socio-demographic characteristics of study participants, such as age, sex, and marital status; level of education (illiterate, primary, secondary, intermediate, university); occupation (student, manual work, semiprofessional/professional; housewife); current smoking; and contact information.

Migraine history from the patients was taken (migraine attacks assessment) in the form of onset of migraine headache in years, type of migraine headache [low frequent episodic migraine (LFEM), high frequent episodic migraine (HFEM), chronic migraine (CM)], presence of aura, severity of migraine attacks using a numerical rating scale, and frequency (number of migraine days per month).

The study participants were taught to use a headache diary. Information on headache features was collected, such as when the attack started and was relieved, triggering factors and associated symptoms, the number of migraine days, and the severity of migraine attacks.

The migraine-specific quality of life questionnaire (MSQ) Version 2.1 is a migraine-specific instrument composed of 14 items designed to measure how migraine affects and/or limits daily functioning. It consists of three domains: role-restrictive (RR): 7 items assessing how migraine limits daily social and work-related activities; role-preventative (RP): 4 items assessing how migraine prevents activities; emotional role (ER): 3 items assessing the emotional impact of migraine Raw total scores were computed and rescaled from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better QOL. The Arabic version of MSQ was used in this study after getting permission and a license from Mapi Research Trust [23].

The intervention program included educational and training components

The educational program construction was based on sheets developed by Med-IQ in collaboration with the National Headache Foundation: 5 tips for explaining migraines to family and friends, 7 steps for getting migraine support at work, planning for a migraine attack at work, medications to prevent and treat migraines, strategies to control and prevent migraines [24], and migraine information retrieved from Mayo Clinic [25].

A simplified lecture presented on a PowerPoint program was done once during the first visit. Its duration was about 30 min, aiming to increase patients’ knowledge about migraine headaches and reduce the impact of migraine in daily life. The session included concise messages about migraine headaches and their causes and risk factors, common triggering factors of migraine to reduce and avoid further attacks, the role of non-pharmacological therapies, and how to get support from family, friends, and at work. Encouraging the patients to use headache dairy? The best ways to deal with migraine attacks and the explanation and demonstration of progressive muscle relaxation and deep breathing training (20–30 min) Educational brochures: all information is written in Arabic with pictorial illustrations and diagrams to help illiterates understand and recall all the important information given previously during the session. The brochures were designed by the researcher based on the educational lecture.

Relaxation training program

Relaxation training consisted of deep breathing exercises and progressive muscle relaxation (PMR). Progressive muscle relaxation script [26] and steps of relaxation exercise for people with headaches retrieved from the London Headache Centre [27]. It was performed daily, and participants kept a record of it. Group meeting sessions for training were held every week for the first 4 weeks at the specialized headache outpatient clinic. Video programs were used for relaxation technique illustration. The participant completed a 15-min PMR session during the enrollment session and was instructed to practice the exercises daily for 8 weeks to achieve at least 60 sessions and to record their headache data daily.

Adherence to the intervention group was maximized by instructional handouts, weekly phone calls, and WhatsApp groups that followed up for the remainder of the study period between educational and final evaluation sessions.

Despite this, there was an attrition (loss of follow-up) in two participants in the intervention group. So analysis was done on 58 participants (28 participants in the intervention group and 30 participants in the control group).CONSORT flowchart of integrated patient education and relaxation program (Fig. 2).

The participants in the control group were advised to adhere to the prescribed medications only and not to change the treatment plan during the study period.

Statistical analysis

The collected data were registered, coded, and statistically analyzed using the statistical package for the social sciences (SPSS) version 25 (Released 2017 by the International Business Machines Corporation, Chicago, USA).

Quantitative data were presented as mean and SD. Qualitative data were presented as numbers and percentages. A Student’s t test was used to compare quantitative data between two independent groups, and a one-way ANOVA test was used for comparisons between more than two groups. The Chi-square test (or Fisher exact test) were used for the comparison of qualitative data. A repeated measure ANOVA test was used to measure changes in different quantitative variables at different time points and Friedman test was used for qualitative variables.

p value less than or equal to 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Table 1 compares socio-demographic and clinical data between the study groups. The majority of participants in both the intervention and control groups were married females. The mean age of the patients was 35.39 ± 10.30 and 40.07 ± 8.37 years in the intervention and control groups, respectively. More than half of the patients in both groups were housewives with an intermediate education. The mean duration since the onset of migraine in the intervention and control groups was 8.21 ± 7.49 years and 8.97 ± 5.81 years, respectively. The majority of patients in both groups did not smoke currently and did not have chronic diseases. Almost half of the patients in the intervention and control groups had chronic migraine. The majority of patients had migraine without aura.

Socio-demographic and clinical data were matched between the study groups. Also, the baseline migraine features and quality of life of the patients were not statistically significant between the two groups.

According to Table 2, after 1 month of follow-up, both groups showed reduced severity of migraine attacks in the form of decreasing the numerical rating scale value, but participants in the intervention group reported a lower headache severity than participants in the control group. The difference became statistically and clinically significant after 3 months of follow-up.

After the intervention, the percentage of patients complaining of chronic migraine (≥ 15 days/month) in the intervention and control groups decreased and shifted to high/low frequent episodic migraine (8–14/4–7 days/month). The reduction in the intervention group was highly statistically and clinically significant compared to the control group.

The average duration of migraine attacks was reduced in the intervention group more than in the control group after 1 month, but the reduction was statistically and clinically significant between the two groups after 3 months of follow-up.

According to Table 3, MSQ scores were increased in patients of both the intervention and control groups in follow-up assessments from baseline to 3 months regarding role-function restriction, role-function prevention, and emotional function. Patients in the intervention group reported significantly higher MSQ scores than patients in the control group at 1 month and 3 months. This was reflected in the quality of life in the form of improving daily routine social and work-related activities, such as time spent with family and friends, leisure activities such as reading or exercising, and the ability to concentrate on work.

Also decrease the need for help in handling routine tasks such as every day household chores, doing necessary business, shopping, or caring for others, and finally decrease the feeling of burden on others because of migraines.

As a result, at 1 and 3 months of follow-up, patients who received the education program and performed the relaxation training according to the protocol had less severity, frequency, and duration of migraine attacks and a better migraine-related quality of life than the control group.

Discussion

The intervention program resulted in a significant reduction in the severity, frequency, and duration of migraine attacks and also had a significant positive effect on improving the participants' quality of life.

In the current study, the majority of participants in both the intervention and control groups were female. This agrees with a study by Mehta and colleagues [28] that studied the additive effect of physical therapies on standard pharmacologic treatment alone in Indian patients with migraine, in which the frequency of females was higher than males.

In the present study, the majority of participants had migraine without aura, which agrees with the International Headache Society's classification that migraine has two basic sub-types: migraine without aura (about 70% of attacks) and migraine with aura (around 30% of attacks) [20].

At the beginning of the program, all participants reported very high scores for the severity, frequency, and duration of migraine attacks, as well as very low scores for QOL, implying that the study participants experience significant migraine-related disabilities and frustrations. This was explained in the Alharbi and Alateeq [29] cross-sectional study that was conducted to investigate the disability associated with migraine attacks. They justified the high degree of baseline disability by saying that chronic migraine is associated with a greater degree of disability than episodic migraine, and in the current study, the majority of patients in both groups had chronic and high-frequency episodic migraine headache (8–14 headache days/month) [29].

Considering the primary outcome of the current study, an improvement not reaching a statistically significant level was noticed between the intervention and control groups as regards the severity, frequency, and duration of migraine attacks 1 month after intervention; however, a highly significant difference was observed between the two groups at 3-month follow-up.

Contrary to the Indian randomized control trial by Gopichandran and colleagues [30], which studied the effectiveness of progressive muscle relaxation and deep breathing exercise on pain, disability, and sleep among patients with chronic tension-type headache, it reported an effective reduction in headache severity, frequency, and attack duration in the experimental group compared to the control group at 1 month, and at 3 months of follow-up, this may be due to Gopichandran and colleagues. A 2021 study was conducted on tension headaches that respond more effectively to muscle relaxation [30]. There was evidence of a higher prevalence of muscular pain and sustained contraction of the head and neck muscles in patients with chronic tension-type headaches [31]. Progressive muscle relaxation also results in an improvement in circulation and craniocervical musculoskeletal function. It also reduces the mental and physical effects of stress [31]. Hence, reducing muscle tension through relaxation techniques is useful in reducing pain severity, frequency, and duration.

In particular, regarding migraine frequency, Meyer and colleagues [32], in their German randomized controlled trial, investigated the effect of 6-week progressive muscle relaxation training on the frequency of migraine headache. They reported a significant reduction in the number of migraine attacks and the number of days with migraine per month in the training group compared to the waiting list, which agrees with the current study [32].

A study by Mehta and colleagues [28] studied the additive effect of yoga and physical therapies to standard pharmacologic treatment alone in Indian patients with migraine, three groups received either standard treatment alone, physical therapy with standard treatment, or yoga therapy with standard treatment. Headache frequency and severity were significantly decreased in all the three groups (p < 0.005). Yoga or physical therapy added to standard treatment showed the best result in reduction of the headache frequency and severity as the current study [28].

Regarding the current study secondary outcome, MSQ scores showed marked significant improvement in Role-Function Restrictive, Role-Function Preventive, and Emotional Function domains in the intervention group compared to the control group.

A significant difference between the two groups concerning migraine quality of life scores was first noted at 1 month follow-up. This could be due to the educational lecture that illustrated knowledge about migraine headache, how to decrease the burden of migraine in daily life, and how to get support from family, friends, and coworkers. This could have an immediate impact on MSQ scores, which measure how migraine affects daily social and work-related activities. This agrees with studies that reported that migraine patient education is believed to be an essential component of migraine patient care [9,10,11].

This agrees with an Asian randomized controlled trial done by Aguirrezabal and colleagues [19] that assessed the effectiveness of a primary care-based patient education program about adjusting the believes and behaviors that stimulate the onset of an attack compared to routine medical care and showed a 50% reduction in the days lost due to migraine-related disability and intensity of pain. They concluded that the provision of suitable information through group education appeared to be effective in reducing migraine attack intensity and disability [19].

Also, progressive muscle relaxation has been shown to have a significant effect on relieving anxiety, depression, depression, fatigue and stress that accompany many medical disorders [14]. This agrees with Kalra and colleagues study, which reports the effectiveness of progressive muscle relaxation in reducing anxiety and psychological distress and improving the quality of sleep of hospitalized older adults [33]. Relaxation training also increases the patients’ control over physiological responses to headache, lowers sympathetic arousal, and reduces stress and anxiety [34].

According to Gopichandran and colleagues [30], who used another tool, the headache impact test (HIT-6), in evaluating headache disability, patients in the experimental group had a significantly lower headache disability impact score, indicating less disability than patients in the control group at 1 month and 3 months follow-up.

One of the barriers to initiating behavioral therapy, according to Minen and colleagues in an observational study, was the belief that additional behavioral therapy would not add to current treatment or self-management practices [35]. This highlights the need for a change in patient expectations about the value of behavioral treatment as part of a comprehensive, patient-centered migraine management plan.

Finally, the current study adds evidence for the effectiveness of a multidisciplinary integrated education and relaxation program in reducing the burden of migraine attacks and improving daily activities among adult migraine patients attending the headache clinic.

At the time of recruitment, we ensured that all patients enrolled in the study would sincerely attend the educational session, perform relaxation training at home, keep a log of activity, receive weekly telephone reminders, and complete monthly assessments. We also planned to enroll 30 patients instead of 25 in each group, assuming a 20% dropout rate. This resulted in a low attrition rate in the study population throughout the study period and compensated for the losses to follow-up.

A limitation of the current study could be that we recruited migraine patients from a single headache clinic, which might affect the generalizability and external validity of the study.

Another limitation was that the patients were informed to stabilize the dose of symptomatic and preventive medications throughout the study period, so we could not measure the effectiveness of the integrated program in reducing medication intake. However, stabilization of the doses for the study period (3 months) allowed an accurate evaluation of the effectiveness of the integrated program between the two groups.

In the current study, we did not measure any psychiatric outcomes, and patients with co-morbid psychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety, and/or personality disorders were excluded because psychiatric comorbidities are known to affect the outcome of chronic headache patients.

Conclusion

Integrated education and progressive relaxation programs have a significant effect on the reduction of migraine attack severity, frequency, and duration, as well as improving migraine-related disability and quality of life among patients.

Availability of data and materials

Data will be available upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- GBD:

-

Global Burden of Disease

- ICHD-3:

-

International Classification of Headache Disorders

- PMR:

-

Progressive muscle relaxation

- QOL:

-

Quality of Life

- TPE:

-

Therapeutic patient education

- YLDs:

-

Years lived with disability

- MSQ:

-

Migraine Specific Quality of life Questionnaire

- EMR:

-

Eastern Mediterranean Region

References

El-Metwally A, Toivola P, AlAhmary K, Bahkali S, AlKhathaami A, Al Ammar SA, et al. The epidemiology of migraine headache in Arab countries: a systematic review. Sci World J. 2020;2020:4790254. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/4790254.

Cooper W, Doty EG, Hochstetler H, Hake A, Martin V. The current state of acute treatment for migraine in adults in the United States. Postgrad Med. 2020;132(7):581–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/00325481.2020.1767402. (Epub 2020 May 27).

Lipton RB, Buse DC, Friedman BW, Feder L, Adams AM, Fanning KM, et al. Characterizing opioid use in a US population with migraine: results from the CaMEO study. Neuro. 2020;95(5):e457–68. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000009324.

Agosti R. Migraine burden of disease: from the patient’s experience to a socio-economic view. Headache J Head Face Pain. 2018;58:17–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.13301.

Gazerani P. A bidirectional view of migraine and diet relationship. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2021;17:435–51. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S282565.

Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, Jensen R, Uluduz D, Katsarava Z. Lifting the burden: the Global Campaign against headache. Migraine remains second among the world’s causes of disability, and first among young women: findings from GBD2019. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):137. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-020-01208-0.

Elisa A, Federica G. Psychological treatment for headache: a pilot study on the efficacy of joint psychoeducational group and relaxation training. J Neurol Neurophysiol. 2016. https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-9562.1000379.

Champarnaud M, Villars H, Girard P, Brechemier D, Balardy L, Nourhashémi F. Effectiveness of therapeutic patient education interventions for older adults with cancer: a systematic review. J Nutr Health Aging. 2020;24(7):772–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-020-1395-3.

Barnason S, White-Williams C, Rossi LP, Centeno M, Crabbe DL, Lee KS, American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke Council, et al. Evidence for therapeutic patient education interventions to promote cardiovascular patient self-management: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017;10(6): e000025. https://doi.org/10.1161/HCQ.0000000000000025.

Wijeratne T, Tang HM, Crewther D, Crewther S. Prevalence of migraine in the elderly: a narrated review. Neuroepidemiology. 2019;52(1–2):104–10. https://doi.org/10.1159/000494758.

American Headache Society. The American Headache Society position statement on integrating new migraine treatments into clinical practice. Headache J Head Face Pain. 2019;59(1):1–18.

Grazzi L, Rizzoli P. Lessons from lockdown—behavioural interventions in migraine. Nat Rev Neurol. 2021;17(4):195–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-021-00475-y.

Campbell JK, Penzien DB, Wall EM. Evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache: behavioral and physical treatments. US Headache Consortium. 2000;1(1):1–29.

Liu K, Chen Y, Wu D, Lin R, Wang Z, Pan L. Effects of progressive muscle relaxation on anxiety and sleep quality in patients with COVID-19. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2020;39: 101132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2020.101132.

Urits I, Burshtein A, Sharma M, Testa L, Gold PA, Orhurhu V, et al. Low back pain, a comprehensive review: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2019;23(3):23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-019-0757-1.

Verhaak AMS, Williamson A, Johnson A, Murphy A, Saidel M, Chua AL, et al. Migraine diagnosis and treatment: a knowledge and needs assessment of women’s healthcare providers. Headache. 2021;61(1):69–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.14027.

Gewirtz A, Minen M. Adherence to behavioral therapy for migraine: knowledge to date, mechanisms for assessing adherence, and methods for improving adherence. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2019;23(1):3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-019-0739-3.

Lipton RB, Hutchinson S, Ailani J, Reed ML, Fanning KM, Manack A, et al. Discontinuation of acute prescription medication for migraine: results from the chronic migraine epidemiology and outcomes (CaMEO) study. Headache. 2019;59(10):1762–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.13642.

Aguirrezabal I, Pérez de San Román MS, Cobos-Campos R, Orruño E, Goicoechea A, Martínez de la Eranueva R, et al. Effectiveness of a primary care-based group educational intervention in the management of patients with migraine: a randomized controlled trial. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2019;20: e155. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1463423619000720.

Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The international classification of headache disorders. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(1):1–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102417738202.

El Missiry A, Sorour A, Sadek A, Fahy T, Abdel Mawgoud M, Asaad T. Homicide and psychiatric illness: an Egyptian study [MD thesis]. Cairo: Faculty of Medicine, Ain Shams University; 2004.

Hatata A, Khalil A, Assad T, AboZeid M, Okasha T. Dual diagnosis in substance use disorders, a study in Egyptian sample, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt (unpublished MD thesis); 2004.

EProvide. Eprovide.mapi-trust.org. 2022 [cited 5 February 2020]. https://eprovide.mapi-trust.org/instruments/migraine-specific-quality-of-life-questionnaire. Accessed May 2022.

Med-IQ [Internet]. Livingwellwithmigraines.com. 2022 [cited 8 October 2019]. https://livingwellwithmigraines.com. Accessed May 2022.

Migraine—Symptoms and causes. Mayo Clinic. 2022 [cited 8 October 2019]. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/migraine-headache/symptoms-causes/syc-20360201. Accessed May 2022.

Progressive Muscle Relaxation Script. [cited 8 May 2022] https://www.law.berkeley.edu/files/Progressive_Muscle_Relaxation.pdf

Relaxation exercises for people with headaches—London Headache Centre. London Headache Centre. 2022 [cited 8 May 2022]. https://londonheadachecentre.co.uk/heahache-information-for-patients/relaxation-exercises-for-people-with-headaches/. Accessed May 2022.

Mehta JN, Parikh S, Desai SD, Solanki RC, Pathak GA. Study of additive effect of yoga and physical therapies to standard pharmacologic treatment in migraine. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2021;12(1):60–6. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1718842.

AlHarbi FG, AlAteeq MA. Quality of life of migraine patients followed in neurology clinics in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. J Family Community Med. 2020;27(1):37–45. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfcm.JFCM_185_19.

Gopichandran L, Srivastsava AK, Vanamail P, Kanniammal C, Valli G, Mahendra J, et al. Effectiveness of progressive muscle relaxation and deep breathing exercise on pain, disability, and sleep among patients with chronic tension-type headache: a randomized control trial. Holist Nurs Pract. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1097/HNP.0000000000000460.

Blaschek A, Milde-Busch A, Straube A, Schankin C, Langhagen T, Jahn K, et al. Self-reported muscle pain in adolescents with migraine and tension-type headache. Cephalalgia. 2012;32(3):241–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102411434808.

Meyer B, Keller A, Wöhlbier HG, Overath CH, Müller B, Kropp P. Progressive muscle relaxation reduces migraine frequency and normalizes amplitudes of contingent negative variation (CNV). J Headache Pain. 2016;17:37. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-016-0630-0.

Kalra N, Khakha D, Satapathy S, Dey S. Impact of Jacobson progressive muscle relaxation (JPMR) and deep breathing exercises on anxiety, psychological distress and quality of sleep of hospitalized older adults; 2021.

Probyn K, Bowers H, Mistry D, Caldwell F, Underwood M, Patel S, CHESS team, et al. Non-pharmacological self-management for people living with migraine or tension-type headache: a systematic review including analysis of intervention components. BMJ Open. 2017;7(8): e016670. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016670.

Minen MT, Azarchi S, Sobolev R, Shallcross A, Halpern A, Berk T, et al. Factors related to migraine patients’ decisions to initiate behavioral migraine treatment following a headache specialist’s recommendation: a prospective observational study. Pain Med. 2018;19(11):2274–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pny028.

Acknowledgements

I delighted to express my respectful thanks to Dr. Mohammed Farouk Allam Professor of public health, Faculty of Medicine—Ain Shams University, for his great help, advice and valuable instructions.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors (SH, AM, MMF, RMA, HAH and DM) had participated in the study design, data management, data analysis, decision-making on content and paper write-up and revision of final draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medicine, Ain Shams University (FMASU M D 231/ 2018), approval letter was obtained from the director of the outpatient clinics to carry out the program, the study was registered in Clinicaltrials.gov, ClinicalTrails.gov Identifier: NCT05039996 and written informed consents that provide information about the program were obtained from participants before starting the intervention.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hisham, S., Manzour, A., Fouad, M.M. et al. Effectiveness of integrated education and relaxation program on migraine-related disability: a randomized controlled trial. Egypt J Neurol Psychiatry Neurosurg 59, 142 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41983-023-00745-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41983-023-00745-0