Abstract

Background

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic autoimmune disease, affecting about 2.5 million people worldwide. Telemedicine is a relatively recent telecommunication tool that has multiple formats such as store-and-forward, interactive video conferencing, remote medical record access, and remote patient monitoring. Telemedicine can be used to assess individuals with MS regarding their disease process, the development and impact of new symptoms as well as inquire about health behaviors that promote effective self-management. In this study, we aimed to evaluate the effect of telemedicine on patient satisfaction, clinical outcome and financial feasibility for MS patients.

Results

Sixty MS patients from the MS unit, at Kafr Elshikh General Hospital, were recruited and divided into 2 groups; 30 in the telemedicine group and 30 in the control group. Both groups were followed up for 12 months. We found a significant difference between the telemedicine group compared to controls as it showed less severe visual symptoms (p 0.006), a smaller number of dropouts (p 0.034) and higher patient satisfaction, with no significant difference between the two groups in the number of relapses, gait, bowel and bladder, lower limb weakness.

Conclusion

Telemedicine was found to be a promising practice that can be used to promote, coordinate and adjust ongoing clinical services of MS patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a neurologic disorder affecting young adults leading to chronic disability which needs long-term follow-up as well as causes a large economic burden both directly and indirectly [1]. It was estimated that in 2019, the direct medical costs of MS were $63.3 billion while the indirect costs were $22.1 billion in the United States alone [2].

Heterogeneous symptoms that vary from one patient to another, including depression, cognitive impairment, sensory and motor manifestation, fatigue, pain, and bowel and bladder (B&B) symptoms [3] make the diagnosis difficult and challenging. This causes a delay in starting treatment resulting in neural damage and cell loss [4].

A breakthrough in the diagnosis and treatment of MS has happened [5]. Early treatment with a disease-modifying therapy (DMT) produces better outcomes; specifically, lower relapse rates [6] reduced disability progression [7] and improved survival [8].

Many MS patients cannot take full advantage of these developments because of a shortage in medical services, especially in rural areas in addition to difficulty in mobility due to their disability [9].

Telemedicine may show some benefits for those patients in follow-up and prognosis [10]. It is defined as “the use of electronic information and communications technology to provide and support health care when distance separates the patients”. Telemedicine has multiple formats, such as store-and-forward, interactive video conferencing, remote medical record access, and remote patient monitoring [11]. This relatively recent technology can be used to assess patients with MS regarding their disease process, the development and impact of new symptoms as well as inquire about health behaviors that promote effective self-management. Telemedicine counselling in general has been shown to be an effective means of promoting positive health behaviors, reducing the impact of secondary conditions across a variety of populations with disabling illnesses, including MS [12].

In the current randomized controlled clinical trial study, we aim to assess the potential benefits and practicality of utilizing telemedicine in the management and support of MS clinic located in a rural area with limited resources. We conducted a comparison between the performance of the MS clinic with telemedicine and without telemedicine across various domains, including clinical outcomes, patient satisfaction, and financial feasibility.

By comparing the two clinic management approaches, we aim to gain insights into the impact of telemedicine on the MS clinic.

Methods

This randomized controlled study was conducted at Kafr Elshikh General Hospital in collaboration with Ain Shams university hospital, in the period between September 2019 to August 2020. Ethical Considerations: Written informed consent was obtained from all enrolled patients and/or their relatives. The medical ethical review board of the faculty of medicine, Ain shams University approved the study—approval number 000017585. Sixty MS patients ≥ 18 years of both sexes were recruited throughout their follow-up in the MS unit at Kafr Elshikh General Hospital. They were diagnosed with MS according to McDonald’s criteria [13]. All subtypes of MS were included. The current study excluded any patient with severe co-morbidity that would reduce life expectancy to less than 6 months (e.g., end-stage oncological diseases or severe cardiac dysfunction) and psychosis or dissociative disorders.

Patients arriving at the MS outpatient clinic, Kafr Elshiekh General Hospital who met inclusion criteria were recruited. The patients were randomized into two groups using sealed envelopes: the telemedicine group (n = 30) and the control group (n = 30) (Fig. 1).

At baseline (T0), history and neurological examination were performed for all patients. The telemedicine group was examined by a trainee from the MS unit at Kafr Elshikh General Hospital first, then connected via video conferencing using Zoom software (Zoom video communications Inc., San Jose, California, USA) with an expert in the MS unit, Ain Shams University Hospital.

During the session, the trainee from the MS unit at Kafr Elshiekh General Hospital conducted a thorough medical history and neurological examination, which included the assessment of study scales, with the patient at the local clinic. The trainee recorded the findings, along with their provisional diagnosis and suggested management plan. Subsequently, the trainee initiated a real-time video conference using the Zoom platform with an expert from the MS unit at Ain Shams University Hospital, who joined the session remotely. The trainee and expert engaged in a collaborative discussion to review the patient's clinical presentation, re-examine the patient with the remote expert's guidance, and formulate an appropriate management plan. The changes in findings and decisions made between the trainee and the expert were recorded during different phases of the session.

The control group was only managed by Kafr Elshikh MS unit trainee without using telemedicine. An evaluation was done at baseline (T0) and after 12 months (T1) for both patient groups including clinical outcome, patient satisfaction using the Utah telehealth patient satisfaction survey [14] and financial feasibility by a direct question to the patient: did telemedicine reduce patients’ healthcare costs?. Clinical outcome was determined based on the number of relapses which is defined as the occurrence of an acute episode of one or more new symptoms, or worsening of existing symptoms of MS, not associated with fever or infection, and lasting for at least 24 h, after a stable period of at least 30 days [15]. Only relapses that were associated with significant functional deterioration and that required corticosteroid treatment were included in the study, Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) [16] and Patient Severity of Symptoms Scale (PSS). We used PSS to follow up on these symptoms: visual symptoms, limb weakness, gait, and (B&B) control. These symptoms were rated on a scale of 1 to 4 [15]. 1 = no complaint, 2 = mild disturbances, 3 = moderate disturbances, and 4 = severe disturbances.

Data were statistically analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. Armonk (2011, IBM Corp, NY, USA). Qualitative data were presented as numbers and percentages that were compared using the Chi-square test. Quantitative data were presented as mean and standard deviation after testing of normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and then compared using an independent t-test or Mann–Whitney test. The statistical significance of the obtained results was judged at the (0.05) level.

Results

The study sample included 60 patients, 16 males and 44 females with a mean of age 31.85 ± 8.78. Patients were randomized into two groups’ telemedicine and a control group each containing 30 patients. There were no significant differences between the telemedicine group and the control group in all baseline (T0) parameters (Tables 1, 2, 3).

Comparison between baseline (T0) and after 12 months (T1) in telemedicine and control groups

In the telemedicine group, EDSS (p < 0.001*) and severity of visual symptoms (p 0.047*) showed improvement at T1 in comparison to T0. The rest of the variables did not show any significant change (Table 4).

Comparison between telemedicine and control groups at T1

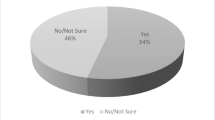

At T1, the telemedicine group showed lesser severity of visual (p 0.006*) (Table 4) and a lower number of patient dropouts (p 0.034*) (Table 5) (Figs. 2, 3).

There were no significant difference between the two groups in the number of relapses (p 0.313) (Table 5) (Fig. 4).

Patient satisfaction

The results of the Utah Telehealth Patient Satisfaction survey are outlined in Table 6. For each survey question, the majority of patients viewed telehealth favorably. For survey questions regarding effective communication, punctuality of the physician, the comfort of the physical exam done through telehealth, and picture and sound quality all of the patients recorded either “Strongly Agree” or “Agree”. Lastly, all patients reported “Strongly Agree” when evaluating if their privacy and confidentiality were protected throughout the visit. Question 8 of the survey assessed patients’ preference for in-person visits by asking if patients would prefer to have seen the specialist in person, to which 83.33% of patients responded by strongly disagreeing.

Discussion

This study presents the assessment of the role of telemedicine in MS patients’ outcomes. We intended to collect and transmit relevant data from patients with MS receiving care in the KFS MS unit to the MS expert in the Ain Shams University Hospital MS unit over 12 months. Overall, participants in the project maintained active engagement in the process of symptom monitoring and rated their experiences with telemedicine monitoring favorably and reported that they were satisfied with the experience.

A large proportion of patients in the telemedicine group reported that the severity of symptoms declined during the course of the study period for every individual symptom monitored. In visual symptoms, the reduction was substantial and statistically significant. However, the reduction in the rest of the symptoms was not statistically significant probably owing to the relatively small sample size.

There was a reduction in the number of relapses in telemedicine group as well but with no statistical significance.

EDSS in the telemedicine group showed significant improvement in T1 compared to T0 reflecting the efficacy of telemedicine. In comparison, Zissman et al. [15] indicated that following up MS patients using telemedicine seems not to present a potential harm to patients by reporting no increase of EDSS after a short follow-up period of 6 months which aimed at assessing changes in EDSS.

Telemedicine neurology consultant (expert) changed the DMT according to changes in the subtype of MS (for example, from relapsing–remitting type to secondary progressive type) in many patients resulting in improved EDSS of the patients (Table 7).

Adherence to treatment represents a challenge in many countries despite the availability of MS medications free of charge [17]. In our study, the number of patient dropouts was zero and 7 patients in telemedicine and control groups, respectively, which was a statistically significant difference. This indicates that telemedicine was very useful in ensuring adherence to treatment in MS patients.

In the telehealth patient satisfaction survey, all patients recorded either “Strongly Agree” or “Agree” regarding effective communication, punctuality of the physician, the comfort of the physical exam done through telehealth, and picture and sound quality. They responded with “Strongly Agree” as well when evaluating if their privacy and confidentiality were protected throughout the visit. Question 8 of the survey assessed patients’ preference to in-person visits by asking if patients would prefer to have seen the specialist in person, to which 83.33% of patients responded by strongly disagreeing.

One of the patients was misdiagnosed as having MS and receiving interferon for 6 months. However, the diagnosis was changed to acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) after telemedicine consultation and the patient was to advised stop interferon, and perform cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis for oligoclonal bands which was negative. After 6 months of follow-up, there was no further disease progression and the patient was strongly satisfied.

These findings suggest that telemedicine monitoring for MS symptoms in an Egyptian population is both feasible and acceptable to those who use it.

Zissman et al. [15] objectively evaluated home telemedicine clinical monitoring of 40 patients with MS over 6 months of implementing telemedicine in the intervention group. As in our study, there was high patient satisfaction with telemedicine. Additionally, the group found a 35% reduction in costs for 67% of the telehealth sample.

By asking patients in our study about their satisfaction with financial spending, they reported that they were spending more on health care before telemedicine. Patients, especially wheel-chaired patients, used to bear the expenses of private travel from rural (Kafr Elshikh) to urban areas to follow up, which cost them thousands of pounds, in addition to accommodation and food expenses.

In agreement with our results, Culpepper et al. [18] and Hatzakis et al. [10] found that telemedicine provides a promising tool to monitor MS patients who live away from their nearest medical center or in rural areas who have a greater barrier to receiving the recommended routine annual specialty care visits.

The advancements in mobile phones with high-quality cameras and the presence of fast mobile internet for transmitting medical information accurately and securely made the use of telemedicine easier to implement. In some of our cases, the mobile was used instead of the laptop, without any significant obstacles and this was time and cost-saving. In light of the current technological development, we could provide remote home telehealth care services, which would cut the cost of transportation even more.

All of the above provides promising evidence that telemedicine may be of direct value to patients in their chronic illness care over time encouraging adherence to follow-up visits and management.

Conclusion

This study indicates that telemedicine was found to be a promising practice that can be used to promote, coordinate and adjust the ongoing clinical services of MS patients. Telemedicine can decrease the medical costs of MS patients.

Availability of data and materials

The raw data of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- B&B:

-

Bowel and bladder

- DMT:

-

Disease-modifying therapy

- EDSS:

-

Expanded Disability Status Scale

- MS:

-

Multiple sclerosis

- PSS:

-

Patient Severity of Symptoms Scale

- 1ry prog. MS:

-

Primary progressive multiple sclerosis

- 2ry prog. MS:

-

Secondary progressive multiple sclerosis

References

Cree BC, Hauser SL. Multiple sclerosis. Jameson J, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Loscalzo J, (eds.), Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 20e. McGraw Hill (NY); 2018

Bebo B, Cintina I, LaRocca N, Ritter L, Talente B, Hartung D, et al. The economic burden of multiple sclerosis in the United States: estimate of direct and indirect costs. Neurology. 2022;98(18):e1810–7.

Tafti D, Ehsan M, Xixis KL. Multiple Sclerosis. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; September 7, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499849/

Tremlett H, Zhao Y, Joseph J, Devonshire V. Relapses in multiple sclerosis are age- and time-dependent. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:1368–74.

Garg N, Smith TW. An update on immunopathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of multiple sclerosis. Brain Behav. 2015;5(9): e00362.

Kappos L, O’Connor P, Radue EW, Polman C, Hohlfeld R, Selmaj K, et al. Long-term effects of fingolimod in multiple sclerosis: the randomized FREEDOMS extension trial. Neurology. 2015;84:1582–91.

Confavreux C, O’Connor P, Comi G, Freedman MS, Miller AE, Olsson TP, et al. Oral teriflunomide for patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis (TOWER): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(3):247–56.

Goodin DS, Reder AT, Ebers GC, Cutter G, Kremenchutzky M, Oger J, et al. Survival in MS: a randomized cohort study 21 years after the start of the pivotal IFN$-1b trial. Neurology. 2012;78(17):1315–22.

Chiu C, Bishop M, Pionke JJ, Strauser D, Santens RL. Barriers to the accessibility and continuity of health-care services in people with multiple sclerosis: a literature review. Int J MS Care. 2017;19(6):313–21.

Hatzakis M Jr, Haselkorn J, Williams R, Turner A, Nichol P. Telemedicine and the delivery of health services to veterans with multiple sclerosis. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2003;40(3):265–82.

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Evaluating Clinical Applications of Telemedicine, Field MJ, (eds.). Telemedicine: a guide to assessing telecommunications in health care. National Academies Press (US); 1996

Dorstyn DS, Mathias JL, Denson LA. Psychosocial outcomes of telephone-based counseling for adults with an acquired physical disability: a meta-analysis. Rehabil Psychol. 2011;56:1–14.

Brownlee WJ, Hardy TA, Fazekas F, Miller DH. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: progress and challenges. Lancet. 2017;389(10079):1336–46.

Hooshmand S, Cho J, Singh S, Govindarajan R. Satisfaction of telehealth in patients with established neuromuscular disorders. Front Neurol. 2021;12:1–5.

Zissman K, Lejbkowicz I, Miller A. Telemedicine for multiple sclerosis patients: assessment using Health Value Compass. Mult Scler. 2012;18:472–80.

Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology. 1983;33(11):1444–52.

Klauer T, Zettl UK. Compliance, adherence, and the treatment of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2008;255(Suppl 6):87–92.

Culpepper WJ II, Cowper-Ripley D, Litt ER, McDowell TY, Hoffman PM. Using geographic information system tools to improve access to MS specialty care in Veterans Health Administration. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2010;47:583–91.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients who subjected to the study.

Funding

There was no funding of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AA recruited the patients, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. MFZ conceived the research concept and strategies. AAA reviewed the manuscript, MMF, AME and MSS performed telemedicine conferences, collected and reviewed the data statistics. All authors discussed the results, read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The medical ethical review board of faculty of medicine, Ain Shams University approved the study—approval number 000017585, and signed informed consents were obtained from the patients and/or their relatives.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declared that they did not have any conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmed, M.A.Ek., Zakaria, M.F., Elaziz, A.A.E.A. et al. Assessment of the role of telemedicine in the outcome of multiple sclerosis patients. Egypt J Neurol Psychiatry Neurosurg 59, 99 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41983-023-00690-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41983-023-00690-y