Abstract

Background

Bone wax is a hemostatic agent widely used in surgery. Since it is neither absorbed nor metabolized, its use remains risky and a potential cause of complications. Even though its MRI radiological characteristics are distinguishable, it is generally misinterpreted as postoperative hematoma or trapped air. We report the first case in literature of brachial plexopathy due to the compressive mass effect of bone wax and the main clues that led us to establish this diagnosis prior to its surgical resection.

Case presentation

A 20-year-old male, victim of stabbing presented with an open wound of the right latero-cervical region with a vascular injury of the V2 segment of the right vertebral artery on CT angiography. He was first admitted for bleeding from the neck uncontrollable with external pressure. The patient underwent an emergency surgical vertebral artery ligation. Forty-eight hours later, he reported a feeling of paresthesia of right arm with right-sided weakness. Neurologic examination revealed a motor deficit of the right triceps and wrist extensor muscles and absence of the triceps reflex. A postoperative compression of the C7 cervical root or the middle trunk of brachial plexus was initially suspected. A cervical MRI demonstrated a T1- and T2-weighted images well-defined right mass located laterally to the spinal cord in the epidural space at the level of C6–C7 vertebrae with a signal-intensity void on both sequences. T2*-weighted images showed no signal attenuation. It did not enhance after contrast administration. An epidural hematoma was less probable since acute hematoma is typically hypointense on T2*-weighted images. Computed tomography helped rule out residual postoperative air trapped in the epidural space based on the density study of the mass compared to air. Finally, a residual surgical foreign material used for packing during the procedure was suspected. The massive use of bone wax was ultimately confirmed by the surgeon and surgically removed with complete immediate postoperative recovery.

Conclusions

This case highlights the importance of a nuanced critical approach of neurosurgeons and neuroradiologists when interpreting postoperative neuroimaging scans of the spine. It is crucial to always consider foreign body-related complications and to review the per-operative procedure in details.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bone wax (BW) is widely used as a hemostatic agent in both cranial and spine surgery. Since it is neither absorbed nor metabolized, various complications have been attributed to its use such as foreign body granuloma, infection, epistaxis, mass effect, altered bone healing, venous sinus thrombosis and soft tissue sarcoma following retained BW [1]. However, it is cost effective and acts immediately making its use always common. In cases of postoperative neurological deficits, it is commonly overlooked as a potential cause. Thus, the diagnosis was mainly readdressed based on postoperative macroscopic or anatomopathological findings. Distinctive neuroradiological features of BW are of a great aid when interpreting postoperative scans in such delicate cases. We present a case of compressive mass effect of bone wax on the middle trunk of the brachial plexus following vertebral artery injury causing a motor deficit of the right arm. The diagnosis was based on the radiological presentation on MRI and CT and confirmed further after the resection of the bone wax.

Case presentation

We present the case of a 20-year-old male, victim of stabbing causing an open wound located in the right latero-cervical region was first admitted to the emergency room for active bleeding from the vessels near the base of the skull which was difficult to control by external pressure. On the initial examination, patient did not present with any neurological deficit. A CT angiography pointed a transection of the V2 segment of the right vertebral artery with preserved adequate collateral vertebral artery circulation. The young man underwent an emergency surgical intervention using hemostatic tamponade with BW which was insufficient to control the bleeding and thus requiring direction ligation of the injured artery. The preoperative assessment did not reveal any cervical nerve root injury homolateral to the injury. Forty-eight hours later, he reported a feeling of electric shock, tingling and radiating numbness down the right arm to the middle finger. He also expressed a feeling of right-sided weakness of the elbow, wrist and finger extension. He had no bladder or bowel incontinence. He remained fully ambulatory and did not complain of lower limbs weakness. Neurologic examination revealed a motor deficit of the right triceps and wrist extensor muscles scored as 4/5 using the muscle grading system and the absence of the triceps reflex.

Considering the persistence of paresthesia and right-sided discrete motor deficit, an electroneuromyography (EMG) study was performed 6 days following the postoperative symptoms onset. It revealed the preservation of motor nerve conduction. We noted the attenuation of sensory nerve action potentials recorded from the median nerve by stimulating the middle finger of the right hand. Needle EMG noted the presence of denervation signs within the following muscles on the right: triceps; extensor digitorum communis and palmar interossei. However, no signs of denervation were noted within the deltoid, the brachioradialis and the paravertebral muscles. Hence, EMG helped addressing the topography of the lesion since C7 root injury often coexists with middle trunk injury and shares clinical features of C7 radiculopathy.

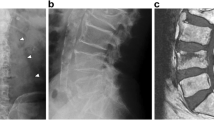

A middle trunk post-traumatic compression was initially suspected. A cervical MRI was performed to investigate the brachial plexus and the potential cause of compression. T1- and T2-weighted images showed a well-defined right mass located laterally to the spinal cord in the epidural space at the level of C6–C7 vertebrae with a signal-intensity void on both sequences (Fig. 1). T2*-weighted images showed no signal attenuation within the mass. It did not enhance after contrast administration. It extended into the right C6–C7 intervertebral foramina exerting mass effect on the cervical spinal cord and causing its displacement to the left side. Despite the compression, no signal abnormality was noted within the spinal cord. Based on these MR findings, an epidural hematoma was less probable since acute hematoma is typically isointense on T1- and T2-weighted images and hypointense on T2*-weighted images [2]. Residual postoperative air trapped in the epidural space causing mass effect could also be discussed [3]. However, computed tomography clearly distinguished the density of air from the density of the mass; the mass was characterized with a higher density than the tracheal air (− 110.7 vs. − 976.9 Hounsfield unit).

MR and CT images of the cervical spine illustrating the mass. a Sagittal T2-weighted image of the cervical spine showing a space-occupying mass located laterally to the spine, extending to the intervertebral foramina of C6–C7 with a signal void. b Sagittal T1-weighted image of the cervical spine showing the same mass characterized also with a signal void. c MR myelography of the cervical spine showing the mass located laterally at the right and extending into the intervertebral foramina of C6–C7. d Axial T2-weighted image on the C6–C7 level showing the mass in low signal intensity located within the epidural space on the right of the cervical spinal cord which is slightly displaced to the left with no signal abnormalities. e Axial T1-weighted image of the same mass, always characterized with a signal void, extending through the intervertebral foramina of C6–C7. f Density comparison of the mass (− 110.7 HU) and the air within the trachea (− 976.9 HU)

After ruling out the differential diagnoses, residual surgical foreign material used for packing during the procedure was suspected. The massive use of bone wax was ultimately confirmed by the vascular surgeon. The bone wax was surgically removed. The paresthesia resolved immediately after surgery. The neurological assessment, 1 week after the surgical intervention, showed no residual motor deficit with full recovery. Thus, the patient’s condition did not require any further physiotherapy or symptomatic treatment.

Discussion

Bone wax is used to seal the cut surface of bone and vessels in different fields of surgery. In spine surgery, its use is very common to attain hemostasis following vertebral artery injury due to the placement of cervical spine screws. It is also used as a marker for spatial orientation when performing intraoperative MRI. Being minimally absorbable, it persists as a foreign material and could be responsible of several complications such as infection, foreign body granuloma, and mass effect [4]. It presents a diagnostic challenge as it has never been suspected as a primary diagnosis in the previously reported cases of compression of the spine and/or nerve roots (Table 1). In fact, it was mainly misdiagnosed as postoperative hematoma, trapped air, artifacts from surgical hardware or retained packing material. Its key characteristic is the signal void in different MRI sequences [5, 6]. Granulomatous reaction of the foreign material of bone wax could be a plausible differential diagnosis in this case. However, its MR imaging characteristics differ and typically show an enhancement of the margins on T1-weighted images with a central void [7, 8]. To our knowledge, our case represents the first report in literature of brachial plexopathy due to the compressive mass effect of bone wax. A case report of radiculopathy was previously described following two lumbar disk surgery due to bone wax mass compressing the dural sac and the spinal roots [8]. A mass effect due to bone wax only, without associated granuloma or hematoma, was described in one unique case of paraplegia following a decompressive surgery of the thoracic spine after the removal of a mass within the T6–T9 vertebrae [9].

This case report adds to the current literature further evidence that the use of bone wax remains risky and explains the thriving bone wax substitute research in the field of hemostatic agents. It further highlights the hallmark MRI characteristic of bone wax which is a signal-intensity void on the different sequences. Finally, a spinal surgeon should always consider an extra-spinal origin of the compression and not overlook a postoperative foreign material complication as an etiology.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- BW:

-

Bone wax

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

References

Das JM. Bone wax in neurosurgery: a review. World Neurosurg. 2018;116:72–6.

Moriarty HK, Cearbhaill RO, Moriarty PD, Stanley E, Lawler LP, Kavanagh EC. MR imaging of spinal haematoma: a pictorial review. Br J Radiol. 2019;92(1095):20180532.

Kaymaz M, Oztanir N, Emmez H, Ozköse Z, Paşaoğlu A. Epidural air entrapment after spinal surgery. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2005;107(5):421–4.

Zhou H, Ge J, Bai Y, Liang C, Yang L. Translation of bone wax and its substitutes: history, clinical status and future directions. J Orthop Transl. 2019;17:64–72.

Karabekır HS, Korkmaz S. Residue bone wax simulating spinal tumour: a case report. Turk Neurosurg. 2010;20:524–6.

Cirak B, Unal O. Iatrogenic quadriplegia and bone wax. Case illustration. J Neurosurg. 2000;92(2 Suppl):248.

Ozdemir N, Gelal MF, Minoglu M, Celik L. Reactive changes of disc space and foreign body granuloma due to bone wax in lumbar spine. Neurol India. 2009;57(4):493–6.

Eser O, Cosar M, Aslan A, Sahin O. Bone wax as a cause of foreign body reaction after lumbar disc surgery: a case report. Adv Ther. 2007;24(3):594–7.

Stein JM, Eskey CJ, Mamourian AC. Mass effect in the thoracic spine from remnant bone wax: an MR imaging pitfall. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31(5):844–6.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This report did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AR—conceptualization, writing initial draft. SN—data collection, editing, supervision. CD: supervision and editing. IZ: supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics committee approval was not considered necessary because it was a case report. Informed consent was obtained from the patient for this study.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nagi, S., Rekik, A., Drissi, C. et al. Bone wax causing a middle trunk plexopathy following vertebral artery injury: a neuroradiological pitfall. Egypt J Neurol Psychiatry Neurosurg 59, 16 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41983-023-00619-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41983-023-00619-5