Abstract

Background

Cerebral small vessel disease (SVD) is associated with acute events such as lacunar and hemorrhagic strokes, or chronic events such as cognitive deficit in the form of subcortical dementia, mood deficit in the form of late onset depression, sphincteric affection, and gait apraxia. Under conditions of moderate blood flow deficit, the inability of sclerotic vessels to dilate due to impairment of the cerebral autoregulation, renders the periventricular white matter seriously ischemic. Therefore, it is important to detect the implications of cerebral large artery disease on the severity of SVD, and the ability of transcranial duplex (TCD) to evaluate it in people at risk.

Methods

Fifty lacunar stroke patients were recruited, and evaluated using MRI brain to assess SVD score, carotid duplex and TCD to assess extracranial and intracranial stenoses, respectively.

Results

Both intracranial and extracranial stenoses showed significant relation to the severity of cerebral SVD. Moreover, there were significant relation between intracranial stenosis and presence of lacuna and EPVS.

Conclusion

Cerebral large artery disease contributes to the pathogenesis and severity of cerebral SVD. Therefore, TCD may be a useful tool for the prediction of occurrence of cerebral SVD in high-risk individuals, especially hypertensives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Stroke is a major health problem in Egypt. There is no currently active national registry for stroke in Egypt and only limited community-based data exist on stroke incidence. If reported rates in these small local studies can be generalized, then the number of new strokes in Egypt per year may be around 150,000 to 210,000. Stroke also accounts for 6.4% of all deaths and thus ranks 3rd after heart disease and gastrointestinal (especially liver) diseases [1].

According to the TOAST (Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment) classification system, which is a classification of subtypes of ischemic stroke using clinical features and the results of ancillary diagnostic studies, includes five categories: large artery atherosclerosis (embolus/thrombosis) 25%, cardioembolism 20%, cerebral small vessel disease (SVD) 25%, stroke of other determined etiology 5%, and stroke of undetermined etiology 25% [2].

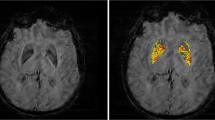

Brain lesions due to SVD are: white matter lesions, lacunar infarcts, and microbleeds. While there are six subtypes of neuroimaging lesions, recent small subcortical infarcts, lacunae of presumed vascular origin, enlarged perivascular spaces (EPS), cerebral microbleeds, central brain atrophy, and white matter hyperintensity (WMH) of presumed vascular origin or leukoaraiosis [3].

Cerebral SVD is associated with acute events like lacunar and hemorrhagic strokes, or chronic events like cognitive deficit in the form of subcortical dementia, mood deficit in the form of late onset depression, sphincteric affection, and gait apraxia [4]. Irrespective to the severity of leukoaraiosis and burden of lacunae and microbleeds, the topographic distribution of lacunae or hemorrhage at strategic locations such as the thalamus, basal ganglia, and internal capsule are associated with increased cognitive and motor manifestations [5].

From the hemodynamic point of view patients with cerebral SVD, occasional drops in their systemic blood pressure could lead to significant decrease in blood flow to the white matter; this effect is attributable to the inability of sclerotic vessels to dilate thus suggesting a presumptive impairment of the cerebral autoregulation, so the periventricular white matter might be considered an area prone to become seriously ischemic under conditions of moderate blood flow deficit [6].

Preventing or delaying disability in patients with cerebral SVD depends not only on the understanding of its pathological processes, but also on the identification of its early stages. However, using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to screen for “subclinical” lesions is not cost effective, while computed tomography (CT) scan is associated with the risks of radiation and the images have not a high quality. Hence, it is important to find a cost benefit method that can be used to simply obtain physiological and hemodynamical data of the disease [7].

The pulsatility index (PI) measured by transcranial duplex (TCD) reflects the degree of downstream vascular resistance. Compared with other organs, the intracranial cerebral vasculature has relatively low downstream vascular resistance, providing a potent blood supply to the brain. One potential cause of increased downstream resistance in the cerebral circulation is narrowing of the small vessels due to lipohyalinosis and microatherosclerosis. Early detection of SVD may be critical in arresting this progressive disease process, allowing aggressive medical treatment including control of vascular risk factors. Thus, a TCD finding of diffusely elevated PIs may suggest previously undiagnosed SVD and prompt a search for and treatment of underlying vascular risk factors. Future studies will be required to determine whether serial TCDs are a useful measure of either disease progression or the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions, such as antiplatelet agents [8].

In this study, we aim to detect the implications of cerebral large artery disease on the severity of SVD, and the ability TCD to evaluate it in people at risk.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional study of 50 patients recruited either inpatient or outpatient clinic departments at Ain Shams University Specialized Hospital from July 2018 to November 2018. All patients provided informed written consent to participate in the study. We recruited both sexes and age above 40 years. The included patients had the diagnosis of cerebrovascular stroke CVS (lacunar infarcts) verified by brain MRI. We excluded patients with bilaterally absent transtemporal window, patients with any other cause of non-ischemic leukoencephalopathy, or patients diagnosed clinically and radiologically as normal pressure hydrocephalus. We also excluded border zone infarcts, large artery atherosclerosis infarcts which defined as cortical or cerebellar lesions and brainstem or subcortical hemispheric lesions greater than 2 cm in diameter on MRI brain, and various types of intracerebral hemorrhage on CT brain. Cardiac source of emboli, e.g., atrial fibrillation (AF), paroxysmal AF, prosthetic valve, valvular heart disease, or hematological diseases and coagulopathies, all are excluded. The included patients were submitted to detailed medical history, thorough general and neurological examination, full metabolic profile, electrocardiogram and transthoracic echocardiogram using Doppler echocardiography unit (GE Vingmed Ultrasound AS, Horten, Norway), carotid and vertebral duplex, and CT brain using (General electric, Boston, MA, USA). All recruited patients were submitted to MRI brain including T1- and T2-weighted images, diffusion-weighted images (DWI), fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), and gradient recalled echo (GRE) T2*-weighted images, using a machine 1.5 T General Electric machine manufactured at United States. Four MRI features were considered: (1) periventricular hyperintensities (PVH) and deep white matter hyperintensities (DWMH) will be rated on the Fazekas scale [9] using FLAIR and T2-weighted sequences. PVH were graded as; 0 = absence, 1 = caps or pencil thin lining, 2 = smooth “halo” and 3 = irregular periventricular hyperintensities extending to deep white matter. Separated DWMH were graded as; 0 = absence, 1 = punctate foci, 2 = beginning confluence of foci, and 3 = large confluent areas. (2) Lacunae that are defined as small (< 20 mm), subcortical lesions of increased signal on T2-weighted and FLAIR, decreased signal T1-weighted images. (3) Microbleeds that are defined as small (< 10 mm), homogeneous, round foci of low signal intensity on GRE image in 7 anatomical locations; gray/white matter, subcortical white matter, basal ganglia, thalamus, brainstem, cerebellum, internal and external capsule [10]. (4) Enlarged perivascular spaces (EPVS) that defined as small sharply delineated structures of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) intensity measuring < 3 mm following the course of perforating vessels, are visualized clearly on T2-weighted image as hyperintensities. They can be rounded or oval. It may be linear if running longitudinally in the centrum semiovale or short linear at the insular or temporal white matter. They will be rated on the potter scale which includes 3 major anatomical regions; centrum semiovale, basal ganglia including; caudate nucleus, internal capsule, thalamus, lentiform nucleus, extreme/external capsule and insular cortex, and midbrain. Basal ganglia and centrum semiovale regions are rated from 0 to 4, in which 0 means no EPVS, 1 means 1–10 EPVS (mild), 2 means 11–20 EPVS (moderate), 3 means 21–40 EPVS (frequent), and 4 means > 40 EPVS (severe), while midbrain region is rated 0 if no EVPS visible or 1 if EPVS visible [11]. We followed Staals and his colleagues to scale cerebral SVD from 0 to 4 in which one point was awarded when DWMH (Fazekas score 2 or 3) and/or PVH (Fazekas score 2 or 3) are present, one point was awarded when 1 or more lacunae are present, one point was awarded when 1 or more microbleeds are present, one point was awarded when moderate to severe (Potter scale grade 2–4) enlarged perivascular spaces are present [12]. All recruited patients were submitted to TCD examination using (EZ-Dop, the DWL Doppler Company, Singen, Germany), where intracranial vessels were examined by the transtemporal, transformational, transorbital and submandibular approach using a 2-MHz probe, intracranial hemodynamic parameters such as the end-diastolic velocity (EDV), the peak systolic velocity (PSV), mean cerebral blood flow velocities (MFV), the resistivity index (RI), and the pulsatility index (PI) are recorded automatically. Breath holding test was done to evaluate vasomotor reactivity (VMR) and asymptomatic carotid stenosis greater than or equal to 70%. 2 MHz probe was fixed above the temporal bone for MCA monitoring and patients were asked to take a normal breath and hold it for 30 s. The breath holding index (BHI) was calculated as follows; ((mean MCA velocity test – mean MCA velocity baseline) ÷ mean MCA velocity baseline) × (100 ÷ seconds of breath holding). A normal breath holding index is greater than or equal to 0.69. Monitoring MCA with 2 MHz probe for 30 min to detect microemboli signals was done [13].

Statistical analysis of data

Recorded data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Quantitative data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Qualitative data were expressed as frequency and percentage. Probability (p value): p value < 0.05 was considered significant, p value < 0.001 was considered as highly significant, p value > 0.05 was considered insignificant.

Results

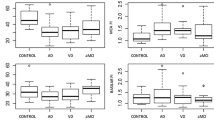

The results of the present study showed that MRI SVD score distribution was Fazekas (48.0%), lacunae (92.0%), EPVS (64.0%) and microbleeds (60.0%) of the included patients (Table 1).

(20%) of included patients had significant (> 50%) extracranial carotid stenosis evaluated by carotid duplex while (Table 2), (52%) had signs of intracranial stenosis evaluated by TCD (Table 3).

Both intracranial and extracranial stenoses had significant relation to the severity of the cerebral SVD, evaluated by MRI SVD score. Moreover, there were significant relation between intracranial stenosis and presence of lacunae and EPVS (Table 4).

In addition, there was statistically significant relation between increased PI of MCA and total MRI SVD score as shown in Table 5.

There was also a statistically significant relation between vasomotor reactivity and EPVS and microbleeds in MRI SVD score as shown in Table 6.

Discussion

In our study, we tried to detect the pathogenesis of cerebral SVD, especially the implication of the cerebral large artery disease, using TCD and extracranial duplex and the ability of TCD, as a simple inexpensive bedside method, to evaluate the severity of cerebral SVD in people at risk.

To evaluate arterial stenosis, we used extracranial duplex and TCD. (20%) of patients included in our study have significant (> 50%) extracranial carotid stenosis, while 52% have signs of intracranial stenosis evaluated by TCD. Both of them have significant relation to the severity of the cerebral SVD, evaluated by MRI SVD score. Additionally, there is a significant relation between intracranial stenosis and presence of lacunae and EPVS.

These results are in agreement with study published in 2018 by Ao et al. who included 928 participants and found a relation between large artery atherosclerosis and cerebral SVD [14]. Another study done by Nam and his colleagues in 2017 found that cerebral SVD is associated with stroke recurrence in patients with large artery atherosclerosis evaluated by MRIand MRA [15]. There was also a relation between large artery atherosclerosis and presence of microbleeds in study done in 2017 by Ding et al. [16]. In addition, Arba et al. in 2017 and Turk et al. in 2016 reported that hypoperfusion was significantly related to the summed cerebral SVD score especially leukoaraiosis [17], 18].

Because cerebral SVD is diffuse and affects the small arteries, arterioles, capillaries and venules, the impairment of cerebral and extracerebral [19] autoregulation is global [20]. Our study emphasizes the same results, patients with poor BHI represent (72%) of studied patients and mostly are hypertensive and have EPVS.

An autopsy study done by Zheng et al. in 2013 found that lacunae were strongly correlated with cerebral atherosclerosis also evidence of thrombi was noticed in neighboring meningeal arteries, suggesting the possibility of artery to artery thromboembolism [21]. However, no microemboli signals detected by TCD in our study, although 44% of them have carotid plaques and 18% of those are unstable plaques.

In 2018 Geurt et al. detected a lower number of perforating arteries and a higher PI in patients with cerebral SVD using two-dimensional phase contrast MRI at 7 T for the first time. In line with previous studies show the relation between Elevated PI of MCA, measured by TCD, and MRI manifestations of the SVD especially PVH and DWMH [22]. In context, 52% of our patients have increased PI of MCA with significant relation to Fazekas and total SVD scores.

Limitations

The sample size was small preventing the proper generalization of our results to a wider segment of the population. Our study lacked healthy controls as it focused mainly on detecting the implications of large artery disease on SVD in patients at risk. Thus, we were unable to calculate the sensitivity and specificity of the various TCD parameters using ROC curve analysis which requires individuals who do not suffer the condition in question, namely SVD. Future studies should explore the sensitivity and specificity of TCD parameters in predicting SVD severity, as our results show it may be a promising tool in that regard.

Conclusions

There is a relation between cerebral large artery disease and severity of cerebral SVD. But we cannot accuse microemboli as a pathogenesis of cerebral SVD. Furthermore, cerebral SVD affects cerebral VMR especially in hypertensive patients, and therefore BHI may be useful for the prediction of cerebral SVD in high-risk people, especially hypertensive.

Availability of data and materials

A master sheet in Excel format is available for patients’ data and their records for the examined points in study. This master sheet is available on contacting the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- AF:

-

Atrial fibrillation

- BHI:

-

Breath holding index

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- CVS:

-

Cerebrovascular stroke

- DWI:

-

Diffusion-weighted imaging

- DWMH:

-

Deep white matter hyperintensities

- EDV:

-

End-diastolic velocity

- EPVS:

-

Enlarged perivascular spaces

- FLAIR:

-

Fluid attenuated inversion recovery

- GRE:

-

Gradient recalled echo

- MCA:

-

Middle cerebral artery

- MFV:

-

Mean flow velocity

- MHz:

-

Mega Hertz

- MRA:

-

Magnetic resonance angiography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- PI:

-

Pulsatility index

- PSV:

-

Peak systolic velocity

- PVH:

-

Periventricular hyperintensities

- SVD:

-

Small vessel disease

- TCD:

-

Transcranial Doppler

- TOAST:

-

Trial of Org 10172 in acute stroke treatment

- WMH:

-

White matter hyperintensities

- VMR:

-

Vasomotor reactivity

References

Abdallah F, Moustafa RR. Burden of stroke in Egypt current status and opportunities. Int J Stroke. 2014;9:52–84.

Adams HP, Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ, Biller J, Love BB, Gordon DL, et al. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke (definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial). Stroke. 1993;24:35–41.

Pantoni L. Definition and classification of small vessel diseases. In: Pantoni L, Gorelick PB, editors. Cerebral small vessel disease first edition 2014, section 1 chapter1; p. 1, 2.

Pantoni L, Poggesi A, Basile AM, Pracucci G, Barkhof F, Chabriat H, et al. Leukoaraiosis predicts hidden global functioning impairment in nondisabled older people; The LADIS (leukoaraiosis and disability in the elderly) study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1095–101.

Pantoni L, Fierini A, Poggesi A, Inzitari D, Fazekas F, Ferro J, et al. Impact of cerebral white matter changes on functionality in older adults; An overview of the LADIS Study results and future directions. Geriatr Gerontol Int J. 2015;15:10–6.

Pantoni L, Garcia JH. Cellular and vascular changes in the cerebral white matter. Annal N Y Acad Sci. 1997;826:92–102.

Ghorbani A, Ahmadi MJ, Shemshaki H. The value of transcranial Doppler derived pulsatility index for diagnosing cerebral small vessel disease. Adv Biomed Res. 2015;4:54.

Kidwell CS, El-Saden S, Livshits Z, Martin NA, Glenn TC, Saver JL. Transcranial Doppler pulsatility indices as a measure of diffuse small vessel disease. J Am Soc Neuroimag. 2001;11:229–35.

Fazekas F, Alavi A, Chawluk JB, Hurtig HI, Zimmerman RA. MR signal abnormalities 1.5 T in Alzheimer dementia and normal aging. Am J Roentgenol. 1987;149:351–6.

Cordonnier C, Potter GM, Jackson CA, Doubal F, Keir S, Sudlowet CLM, et al. Improving interrater agreement about brain microbleeds, development of the Brain Observer MicroBleed Scales (BOMBS). Stroke. 2009;49:94–9.

Potter GM, Chappell FM, Morris Z, Wardlaw J. Cerebral perivascular spaces visible on magnetic resonance imaging; development of a qualitative rating scale and its observer reliability. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015;39(4):224–31.

Staals J, Makin SJ, Doubal FN, Dennis MS, Wardlaw JM. Stroke subtype, vascular risk factors, and total MRI brain small vessel disease burden. Neurol J. 2014;83:1228–34.

Alwatban M, Edward JT, Abdullah A, Daniel LM, Gregory RB. The breath-hold acceleration index: a new method to evaluate cerebrovascular reactivity using transcranial Doppler. J Neuroimaging. 2018;28(4):429–35.

Ao DH, Zhai FF, Han F, Zhou LX, Ni J, Yao M, et al. Large vessel disease modifies the relationship between kidney injury and cerebral small vessel disease. Front Neurol. 2018;9:498.

Nam KW, Kwon HM, Lim JS, Han MK, Nam H, Lee YS. The presence and severity of cerebral small vessel disease increases the frequency of stroke in a cohort of patients with large artery occlusive disease. PLoS ONE 2017; 12(10).

Ding L, Hong Y, Peng B. Association between large artery atherosclerosis and cerebral microbleeds: a systematic review and meta analysis. Stroke and Vascular Neurology. 2017;2:49.

Arba F, Mair G, Carpenter T, Sakka E, Sandercock PAG, Lindley RI, et al. Cerebral white matter hypoperfusion increases with small vessel disease burden. Data from the third international stroke trial. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2017;26(7):1506–13.

Turk M, Zaletel M, Oblak JP. Characteristics of cerebral hemodynamics in patients with ischemic leukoaraiosis and new ultrasound indices of ischemic leukoaraiosis. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;25(4):977–84.

Staszewski J, Skrobowska E, Piusinska-Macoch R, Brodacki B, Stępień A. Cerebral and extracerebral vasoreactivity in patients with different clinical manifestations of cerebral small vessel disease. J Ultrasound Med. 2018;00:1–13.

Guo ZN, Xing Y, Wang S, Hongyin M, Liu J, Yang Y. Characteristics of dynamic cerebral autoregulation in cerebral small vessel disease: diffuse and sustained. Sci Rep. 2015;5:15269.

Zheng L, Vinters HV, Mack WJ, Zarow C, Ellis WG, Chui HC. Cerebral atherosclerosis is associated with cystic infarcts and microinfarcts but not Alzheimer pathologic changes. Stroke. 2013;44(10):2835–41.

Geurts LJ, Zwanenburg JJM, Klijn CJM, Luijten PR, Biessels GJ. Higher pulsatility in cerebral perforating arteries in patients with small vessel disease related stroke, a 7T MRI study. Stroke. 2018;50(1):62–8.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Authors declare that they received no funding for their study. No funding body had role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors, MT, AE, SH and MH have contributed actively and equally in the production of research by recruiting patients, examining them, TCD assessment, data entry and scientific writing and revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by Faculty of Medicine, Ain-Shams University ethical committee in July 2018. All patients provided informed written consent to participate in the study.

Consent for publication

All participants provided informed written consent to participate in the study to be published.

Competing interests

Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tawfik, M.M., Ebrahim, A., Hamed, S. et al. Transcranial Doppler assessment of patients with cerebral small vessel disease. Egypt J Neurol Psychiatry Neurosurg 58, 156 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41983-022-00591-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41983-022-00591-6