Abstract

Background

About 40–70% of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) develop cognitive impairment (CI) throughout their life. We aim to study the influence of MS on cognitive changes. This is a case–control study of fifty patients with MS who met the revised 2017 Mc Donald Criteria and fifty age- and sex-matched healthy subjects. The Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) was used to assess the degree of disability, and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) scoring system was used to assess cognitive function.

Results

MS patients show low total MoCA score than the controls. Total MoCA scores were lower in patients with CI versus those with intact cognition. CI was higher in those with a longer duration of illness and a high EDSS. MoCA was positively correlated with education level but negatively with EDSS and disease duration.

Conclusion

MoCA scale has optimal psychometric properties for routine clinical use in patients with MS, even in those with mild functional disability. The longer the disease duration and the higher the EDSS, the lower the MoCA score and the higher the education level, the higher the MoCA score. As for the profile of cognitive dysfunction in patients with MS, the domains most frequently failed by the patients were memory, attention, visuospatial learning, and language.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory and immune-mediated disease of the central nervous system characterized by the development of focal demyelination and neuronal injury in functionally or anatomically related regions involved in cognitive processing such as the white matter, the cerebral cortical and deep gray matter, and the hippocampus [1,2,3].

Besides, motor and autonomic symptoms, MS was verified to have a higher risk of developing a wide range of psychobehavioral disorders, such as depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, sleep disorders, schizophrenia, and other psychotic disorders, all of which share cognitive decline [4,5,6].

Epidemiological studies reported frequencies of cognitive impairment (CI) in patients with MS between 40 and 70% of subcortical profiles [7, 8]. The presence of cognitive and psychological difficulties in people with MS contributes more to withdrawal from work and unemployment than physical disability [9].

The CI is more common in advanced stages of the disease, although it can occur at any time. Exceptionally, CI is the first manifestation of MS, and these patients develop a progressive cognitive deterioration from the beginning of the disease [10]. In a recent study, persons with newly diagnosed MS are more likely to have subtly CI than controls regardless of race/ethnicity [11].

The most frequently altered cognitive domains are sustained attention, speed of information processing, abstract reasoning, executive functions, and long-term verbal and visual memory. The involvement of cortical functions such as aphasia or negligence is exceptional [12,13,14].

The precise mechanisms responsible for MS-related CI are complex and tangled and not completely known [15]. CI is associated with both structural injury and functional impairment of neuronal networks in the MS brain [16] or could be driven by a synaptopathy facilitated by the CNS inflammatory situation [3].

Whether early CI in MS varies by race/ethnicity is unknown. Non-Hispanic blacks, especially women, were disproportionately affected and had less common, earlier progressive MS phenotypes [17].

Along with parameters of a higher disease burden, APOE ε4 homozygosity was identified as a potential predictor of cognitive performance in patients with clinically isolated syndrome and early relapsing–remitting MS [18].

There is no agreement on what should be the most suitable instruments for the exploration of CI in MS. Batteries of short and large tests are available. It is very important to carry out a neuropsychological screening evaluation that can identify cognitive impairment before a more extensive and comprehensive evaluation is performed [19, 20].

Among the psychometric cognitive assessment that has been used commonly in research of MS, MoCA that has been recommended by the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke and Canadian Stroke Network was defined as a fast, reliable, accurate, and high-sensitive test to detect mild CI in 90% of cases and used as an alternative to the Mini-Mental Status Examination [21]. Single cutoff scores are frequently used to classify cognitive impairment in different MoCA versions [22]. A cutoff of ≤ 22 points was adopted to differentiate cognitively unimpaired individuals from possible mild CI [23].

We aim to assess the effect of MS on cognitive functions using the MoCA scoring system and investigate the relationship of MoCA scores with different confounding factors.

Methods

A case-control study was conducted at the multiple sclerosis clinic at Baghdad Teaching Hospital / Medical City between November 2019 to November 2020. The study was approved by the Iraqi Committee of Medical Specialization (Decision No. 931; Date 1/3/2020) and an informed consent was ensured from all the participants.

The participants consisted of 50 MS patients in the remission phase (42 relapsing–remitting and 8 with secondary progressive) aged 20–54 years who met the 2017 revised Mc Donald Criteria [24]. Another 50 age- and sex-matched controls aged were studied. Duration of patient’s illness ranging from 1 year to > 20 years. All patients were carefully followed up at a single MS center and they were under immunomodulatory therapy, such as interferon or glatiramer acetate.

Patients under treatment that have a significant impact on their cognitive performance, with a history of impaired hearing function, diagnosed psychiatric disorder, or cognitive impairment before MS diagnosis were excluded from the study.

A detailed neurological examination was done by a senior neurologist. The neuropsychological assessment were both performed within 1 week. The EDSS [25] is used to evaluate the degree of disability (the higher the score, the worse the patient’s disability). The scale ranges from 0 (normal) to 10 (death due to MS) in 20-step scale scores (with 0.5-unit increments). EDSS steps 1.0–4.5 refer to fully ambulatory patients, and the precise step number is defined by the functional system score(s), while EDSS steps 5.0–9.5 are mostly described by impairment of ambulation [26].

Cognitive functions were assessed using the MoCA scale. MoCA consists of 30 items divided into the domains of attention, language, memory, visuospatial, executive functions, and orientation and scored accordingly from 0 to 30 with a cutoff value of 26. A score of 26 or above was considered normal [27], 25 to 23 as mild cognitive impairment, 23 to 11 as moderate cognitive impairment, and 10 and below is severe cognitive impairment [28]. Accordingly, MoCA score ranges from 14 to 25 refers to impaired cognition, and from 27 to 30 goes with intact cognition [29].

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software, version 25 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Released 2017, Armonk, NY: IBM Corporation, USA). Quantitative variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and analyzed with an independent student t test. Categorical variables were expressed as counts and percentages or median and range and analyzed with a Chi-square test.

The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to evaluate the EDSS and total MoCA in the context of discrimination between patients with MS and controls. Correlations between different quantitative variables were performed with two-tailed Pearson's correlation analysis. For all tests, a difference of variables with statistical significance was considered when p < 0.05.

Results

Table 1 shows the basic demographic data of the study population. No significant difference was noticed between the patients with MS and controls regarding age and gender, employment, and years of educations.

Total MoCA score was significantly lower in patients with MS than in the control group (p < 0.001). Similarly, the score of all cognitive domains was significantly less in the patients versus the controls (Table 2).

The duration of illness and the EDSS were significantly higher in patients with low MoCA scores (p = 0.001, p < 0.001, respectively). On the contrary, the education level was significantly higher in those with intact cognition (p < 0.001), as shown in Table 3.

The total MoCA score was significantly lower in those with impaired cognition (p < 0.001). Likewise, all cognitive domains were significantly lower in those with impaired as compared to those with intact cognition apart from the language domain which is statistically insignificant between the two subgroups (p = 0.441) as illustrated in Table 4.

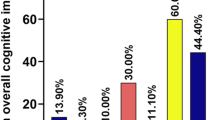

As for the profile of major domains of cognitive performance used in our study. In descending manner, the domains most frequently impaired in MS patients were memory (42, 84%), attention (32, 64%), visuospatial learning (26, 52%), language (20, 40%), naming (9, 18%), abstract (8, 16%), and orientation (6, 12%), as shown in Table 5.

Pearson’s correlation was made between MoCA scores and confounding factors (education level, EDSS, and disease duration), as demonstrated in Table 6.

Total MoCA score was negatively correlated with EDSS (r = − 0.879, p < 0.001) and disease duration (r = − 0.754, p < 0.001), while it was positively correlated with education level (r = 0.623, p < 0.001) (Fig. 1).

Discussion

Because of the complexity and unusual presentation of MS symptoms, there are no markers specific and the diagnosis is challenging. Diagnosis mainly depends on the medical history and neurological examination, magnetic resonance imaging with contrast, cerebrospinal fluid analysis (basic, microbial, cytopathological assessment, oxidative enzymes, and tests for IgG index), visual and somatosensory evoked potentials as well as cognitive tests [30]. Nonetheless, the diagnosis could be delayed for several years especially in the presence of mental and physical comorbidities [31, 32].

Given the fact that cognitive disorders are among the common problems in patients with MS [33], the present study aimed to evaluate the MoCA score (as an important cognitive assessment) in patients with MS based on age, gender, level of education, duration of illness, and EDSS (as important individual characteristics).

Forty-eight percent of our patients with MS have CI. A finding reflects the underlying inflammatory and neurodegenerative pathological features of the disorder [19].

Gender had no significant impact on the cognitive function of the participants, which harmonizes the results obtained by other researchers [34,35,36]. Benedict and colleagues [33] recognized the male gender as one of the risk factors for CI in MS patients. On the reverse, Shaygannejhad and colleagues [37] reported more cognitive complications in women compared to men. This lack of consistency between the results might be due to different MS diseases, duration of disease, type of cognitive test, the difference in sample size, and low sensitivity of cognitive assessment tools.

In the present study, age affect cognitive function as a confounding variable, which is in contradiction with the findings of Hassanshahi and coworkers [36]. However, the findings were similar to the results obtained by other groups [34, 35, 38], who reported a decrease in the cognitive level of subjects by aging or a significant relationship between age and learning, memory, and executive functions based on different batteries. This lack of consistency between the results might be due to the different age ranges, and evaluation of higher ages might show a greater impact of age on the cognitive status of individuals or to differences in the type of cognitive test.

In this study, patients with CI have a longer duration of illness along with a significant relationship between CI illustrated as low MoCA score with disease duration. This suggests that as the disease progresses, cognitive deficits tend to extend.

Amato and colleagues [39] examined 50 patients with a short disease duration. Ten years later, the short-term verbal memory, abstract reasoning, and linguistic abilities were impaired [40]. In addition, the proportion of patients who were cognitively preserved decreased over the same time from 74% at baseline to 44%; meanwhile, the proportion of patients with mild or moderate impairment tended to increase.

Earlier cross-sectional studies found a weak or no correlation between CI and disease duration [41,42,43], while other cross-sectional studies [44,45,46] using the different battery of neuropsychological tests observed an increment in the proportion of CI over ensuing years.

The long-term CI evolution could be related to the progression of both gray matter and white matter pathology. CI was progressed continuously and paralleled by atrophy and lesion accumulation [47, 48].

In this study, low education attainment is associated with worse cognitive performance in patients with MS. This finding is in line with the results obtained by many groups of researchers [37, 49,50,51], who posed a significant relationship between cognitive disorders and level of education even in patients without gray matter atrophy. The close correlation between CI and education level coincided with the results obtained by Caparelli-Dáquer and coworkers [52], who reported that the highest scores on the correct answer to the Judgment of Line Orientation Test were in men and higher education groups.

On the contrary to these results, other groups of researchers demonstrated that level of education did not act as a predictor for cognitive dysfunction [35, 36, 53]. This inconsistency between the results is due to different cognitive assessment tools, different sample populations, and sizes.

A marked association between CI and the individual physical state (measured by the EDSS) was shown in our study plus the EDSS was negatively correlated with the MoCA score. These findings were in harmony with those reported elsewhere [46, 54,55,56]. In a study conducted on 92 consecutive patients with relapsing–remitting MS in whom the EDSS scores were ≤ 2.5, cognitive functions were impaired [57] suggesting that cognitive dysfunction can occur early in the disease [58, 59].

Finally, the pattern of CI found in patients with MS could be essentially indicative of reduced information processing speed causing intellectual slowing, attentional problems, impairment in abstract reasoning, problem-solving, and memory dysfunction as distinctive features of “subcortical dementia”. This condition could be attributable to the interruption of the neural connections among cortical associative areas as well as between cortical and subcortical structures as a consequence of demyelination and axonal degeneration.

This research has a few limitations that should be considered. First, we enrolled a small sample size, and the type of MS being confined to relapsing–remitting and secondary progressive phenotypes. Second, we could not evaluate the influence of family history, types, or laboratory parameters. Third, data regarding certain factors, such as those related to environmental conditions, psychosocial characteristics, and genetics, were not part of the data set. Finally, we did not test the effect of treatment on cognitive functions.

We recommend future studies of large cohorts including all MS phenotypes. Further studies of cognitive function at diagnosis and in the early disease course are required to identify the true prevalence of CI at diagnosis, its incidence thereafter, factors contributing to its development, and insight into its pathogenesis. The heterogeneity of the neuropsychological tests previously used to assess cognition in MS has undoubtedly contributed to the considerable variation in the reported prevalence of cognitive deficits. Future neuropsychological research should use practical, validated, and accurate screening tools that are also applicable in a clinical setting, such as Brief International Cognitive Assessment for MS.

Conclusions

MoCA scale has optimal psychometric properties for routine clinical use in patients with MS, even in those with mild functional disability (EDSS). This finding can remind clinicians regarding the importance of considering this to identify MS patients at high risk of CI earlier. Our study also concludes that the longer the disease duration and higher EDSS, the lower the MoCA score, and the higher the education level, the higher the MoCA score. As for the profile of CI, the domains most frequently affected were memory, attention, visuospatial learning, and language.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- CI:

-

Cognitive impairment

- EDSS:

-

Extended disability severity score

- MoCA:

-

Montreal cognitive assessment

- MS:

-

Multiple sclerosis

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

References

DeLuca GC, Yates RL, Beale H, Morrow SA. Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis: clinical, radiologic and pathologic insights. Brain Pathol. 2015;25:79–98.

Dendrou CA, Fugger L, Friese MA. Immunopathology of multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:545–58.

Geloso MC, D’Ambrosi N. Microglial pruning: relevance for synaptic dysfunction in multiple sclerosis and related experimental models. Cells. 2021;10:686.

Tanaka M, Vécsei L. Monitoring the redox status in multiple sclerosis. Biomedicines. 2020;8(10):406.

Huang YC, Chien WC, Chung CH, Chang HA, Kao YC, Wan FJ. Risk of psychiatric disorders in multiple sclerosis: a nationwide cohort study in an Asian population. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2021;17:587–604.

Tanaka M, Vécsei L. Editorial of Special Issue “Crosstalk between depression, anxiety, and dementia: comorbidity in behavioral neurology and neuropsychiatry.” Biomedicines. 2021;9(5):517.

DiGiuseppe G, Blair M, Morrow SA. Prevalence of cognitive impairment in newly diagnosed relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2018;20:153–7.

Jelinek PL, Simpson S, Brown CR, Jelinek GA, Marck CH, De Livera AM, et al. Self-reported cognitive function in a large international cohort of people with multiple sclerosis: associations with lifestyle and other factors. Eur J Neurol. 2019;26:142–54.

McNicholas N, O’Connell K, Yap SM, Killeen RP, Hutchinson M, McGuigan C. Cognitive dysfunction in early multiple sclerosis: a review. QJM. 2018;111:359–64.

Moreno-Torres I, Sabín-Muñoz J, García-Merino A. Multiple sclerosis: epidemiology, genetics, symptoms, and unmet needs. Chapter 1. Emerging drugs and targets for multiple sclerosis. 2019; p. 1–32.

Amezcua L, Smith JB, Gonzales EG, Haraszti S, Langer-Gould A. Race, ethnicity, and cognition in persons newly diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2020;94(14):e1548–56.

Van Schependom J, D’hooghe MB, Cleynhens K, D’hooge M, Haelewyck MC, De Keyser J, et al. Reduced information processing speed as primum movens for cognitive decline in MS. Mult Scler J. 2015;21(1):83–91.

Gromisch ES, Fiszdon JM, Kurtz MM. The effects of cognitive-focused interventions on cognition and psychological well-being in persons with multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2020;30:767–86.

Macías IMÁ, Ciampi E. Assessment and impact of cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis: an overview. Biomedicines. 2019;7:22.

Di Filippo M, Portaccio E, Mancini A, Calabresi P. Multiple sclerosis and cognition: synaptic failure and network dysfunction. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2018;19:599–609.

Gaetani L, Salvadori N, Chipi E, Gentili L, Borrelli A, Parnetti L, Di Filippo M. Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis: lessons from cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers. Neural Regen Res. 2021;16:36–42.

Romanelli RJ, Huang Q, Lacy J, Hashemi L, Wong A, Smith A. Multiple sclerosis in a multi-ethnic population from Northern California: a retrospective analysis, 2010–2016. BMC Neurol. 2020;20:163.

Engel S, Graetz C, Salmen A, Muthuraman M, Toenges G, Ambrosius B, et al. Is APOE ε4 associated with cognitive performance in early MS? Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2020;7(4): e728.

Rocca MA, Amato MP, De Stefano N, Enzinger C, Geurts JJ, Penner IK, et al. Clinical and imaging assessment of cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:302–17.

Kalb R, Beier M, Benedict RH, Charvet L, Costello K, Feinstein A, et al. Recommendations for cognitive screening and management in multiple sclerosis care. Mult Scler J. 2018;24:1665–80.

Ashrafi F, Behnam B, Ahmadi AM, Taheri SM, Haghighatkhah HR, Pakdaman H, et al. Correlation of MRI findings and cognitive function in multiple sclerosis patients using Montreal Cognitive Assessment test. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2016;30:357.

Wong A, Law LSN, Liu W, Wang Z, Lo ES, Lau A, et al. Montreal cognitive assessment one cutoff never fits all. Stroke. 2015;46:3547–50.

Carson N, Leach L, Murphy KJ. A re-examination of Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA) cutoff scores. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;33:379–88.

Thompson AJ, Banwell BL, Barkhof F, Carroll WM, Coetzee T, Comi G, et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(2):162–73.

Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology. 1983;33(11):1444–5218.

Hatipoglu H, Kabay SC, Hatipoglu MG, Ozden H. Expanded disability status scale-based disability and dental-periodontal conditions in patients with multiple sclerosis. Med Princ Pract. 2016;25:49–55.

Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, et al. The Montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:695–9.

Chang YT, Chang CC, Lin HS, Huang CW, Chang WN, Lui CC, et al. Montreal cognitive assessment in assessing clinical severity and white matter hyperintensity in Alzheimer’s disease with normal control comparison. Acta Neurol. 2012;21:64–73.

Guo QH, Cao XY, Zhou Y, Zhao QH, Ding D, Hong Z. Application study of quick cognitive screening test in identifying mild cognitive impairment. Neurosci Bull. 2010;26(1):47–54.

Ömerhoca S, Akkaş SY, İçen NK. Multiple sclerosis: diagnosis and differential diagnosis. Arch Neuropsychiatry. 2018;55(Suppl. 1):S1–9.

Hoang H, Laursen B, Stenager EN, Stenager E. Psychiatric co-morbidity in multiple sclerosis: the risk of depression and anxiety before and after MS diagnosis. Mult Scler J. 2016;22:347–53.

Thormann A, Sørensen PS, Koch-Henriksen N, Laursen B, Magyari M. Comorbidity in multiple sclerosis is associated with diagnostic delays and increased mortality. Neurology. 2017;89:1668–75.

Benedict RH, Zivadinov R. Risk factors for and management of cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7:332–42.

Vanotti S, Smerbeck A, Eizaguirre MB, Saladino ML, Benedict RRH, Caceres FJ. BICAMS in the Argentine population: relationship with clinical and sociodemographic variables. Appl Neuropsychol Adult. 2018;25:424–33.

Pouramiri M, Azimian M, Akbarfahimi N, Pishyareh E, Hossienzadeh S. Investigating the relationship between individual and clinical characteristics and executive dysfunction of multiple sclerosis individuals. Arch Rehabil. 2019;20:114–23.

Hassanshahi E, Asadollahi Z, Azin H, Hassanshahi J, Hassanshahi A, Azin M. Cognitive function in multiple sclerosis patients based on age, gender, and education level. Acta Med Iran. 2020;58(10):500–7.

Shaygannejad V, Afshar H. The frequency of cognitive dysfunction among multiple sclerosis patients with mild physical disability. J Isfahan Med Sch. 2012;29:167.

Tam JW, Schmitter-Edgecombe M. The role of processing speed in the brief visuospatial memory test–revised. Clin Neuropsychol. 2013;27:962–72.

Amato MP, Ponziani G, Pracucci G, Bracco L, Siracusa G, Amaducci L. Cognitive impairment in early-onset multiple sclerosis Pattern, predictors, and impact on everyday life in a 4-year follow-up. Arch Neurol. 1995;52:168–72.

Amato MP, Ponziani G, Siracusa G, Sorbi S. Cognitive dysfunction in early-onset multiple sclerosis: a reappraisal after 10 years. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:1602–6.

Lynch SG, Parmenter BA, Denney DR. The association between cognitive impairment and physical disability in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2005;11:469–76.

Rogers JM, Panegyres PK. Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis: evidence-based analysis and recommendations. J Clin Neurosci. 2007;14:919–27.

Chiaravalloti ND, DeLuca J. Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:1139–51.

Achiron A, Chapman J, Magalashvili D, Dolev M, Lavie M, Bercovich E, et al. Modeling of cognitive impairment by disease duration in multiple sclerosis: a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2013;8: e71058.

Dackovic J, Pekmezovic T, Mesaros S, Dujmovic I, Stojsavljevic N, Martinovic V, et al. The Rao’s Brief Repeatable Battery in the study of cognition in different multiple sclerosis phenotypes: application of normative data in a Serbian population. Neurol Sci. 2016;37:1475–81.

Ruano L, Portaccio E, Goretti B, Niccolai C, Severo M, Patti F, et al. Age, and disability drive cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis across disease subtypes. Mult Scler. 2017;23:1258–67.

Ouellette R, Bergendal Å, Shams S, Martola J, Mainero C, Kristoffersen M, et al. Lesion accumulation is predictive of long-term cognitive decline in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2018;21:110–6.

Daams M, Steenwijk MD, Schoonheim MM, Wattjes MP, Balk LJ, Tewarie PK, et al. Multi-parametric structural magnetic resonance imaging in relation to cognitive dysfunction in long-standing multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2016;22:608–19.

Aksoy S, Timer E, Mumcu S, Akgün M, Kırak E, Örken DN, et al. Screening for cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis with MOCA test. Turk J Neurol. 2013;19:52–5.

Rimkus CM, Avolio IMB, Miotto EC, Pereira SA, Mendes MF, Callegaro D, et al. The protective effects of high-education levels on cognition in different stages of multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2018;22:41–8.

Eijlers AJC, Meijer KA, van Geest Q, Geurts JJG, Schoonheim MM. Determinants of cognitive impairment in patients with multiple sclerosis with and without atrophy. Neuroradiology. 2018;288:544–51.

Caparelli-Dáquer EM, Oliveira-Souza R, Moreira Filho PF. Judgment of line orientation depends on gender, education, and type of error. Brain Cogn. 2009;69:116–20.

Maloni H. Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. J Nurse Pract. 2018;14:172–7.

Patti F, Nicoletti A, Messina S, Bruno E, Fermo SL, Quattrocchi G, et al. Prevalence and incidence of cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis: a population-based survey in Catania, Sicily. J Neurol. 2015;262(4):923–30.

Amato MP, Prestipino E, Bellinvia A, Niccolai C, Razzolini L, Pastò L, et al. Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis: an exploratory analysis of environmental and lifestyle risk factors. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(10): e0222929.

Carotenuto A, Moccia M, Costabile T, Signoriello E, Paolicelli D, Simone M, et al. Associations between cognitive impairment at onset and disability accrual in young people with multiple sclerosis. Sci Rep. 2019;9:18074.

Migliore S, Ghazaryan A, Simonelli I, Pasqualetti P, Squitieri F, Curcio G, et al. Cognitive impairment in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients with very mild clinical disability. Behav Neurol. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/7404289.

Dagenais E, Rouleau I, Demers M, Jobin C, Roger E, Chamelian L, et al. Value of the MoCA test as a screening instrument in multiple sclerosis. Can J Neurol Sci. 2013;40(3):410–5.

Oset M, Stasiolek M, Matysiak M. Cognitive dysfunction in the early stages of multiple sclerosis—how much and how important? Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-020-01045-3.

Acknowledgements

We thank assistant professor Dr. Qasim Al-Mayah from the Research Medical Unit/College of Medicine/Al-Nahrain University for helping in statistical analysis.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors have directly participated in the preparation of this manuscript and have approved the final version submitted. ‘NS’ clinically examined and referring migraineurs patients. ‘TA’ and ‘FH’ did the electrodiagnostic tests. ‘FH’ and ‘TA’ drafted the manuscript. ‘NS’, ‘TA', and 'FH' conceived the study and participated in its design and interpretation. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Iraqi Board for Medical Specialization (order no. 931: date: 1/3/2020. Written consent for participation from all subjects was ensured.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Al-Falaki, T.A., Hamdan, F.B. & Sheaheed, N.M. Assessment of cognitive functions in patients with multiple sclerosis. Egypt J Neurol Psychiatry Neurosurg 57, 127 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41983-021-00383-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41983-021-00383-4