Abstract

Background

Atherosclerotic intracranial arterial stenosis (ICAS) is one of the most common causes of stroke worldwide and is associated with a high risk of recurrent stroke. Patients with a recent transient ischemic attack (TIA) or stroke and severe stenosis (70 to 99% of the diameter of a major intracranial artery) are at particularly high risk for recurrent stroke in the territory of the stenotic artery (approximately 23% at 1 year) despite medical treatment. Therefore, alternative therapies are urgently needed for these patients.

Objective

To determine the efficacy and safety of angioplasty with stenting in medically refractory ICAS and to compare its effectiveness with optimal medical treatment.

Subjects and methods

Fifty patients with symptomatic ICAS despite medical treatment (i.e, recurrent stroke or TIA) were enrolled and equally randomized in a prospective study where twenty-five patients underwent angioplasty with stenting and twenty-five patients received optimal medical treatment. Clinical assessment with NIHSS and mRS were done at 0, 3, and 6 months, and transracial Doppler (TCD) assessment of ICAS was done at 0 and 3 months after treatment.

Results

The interventional group had a better clinical outcome with mean NIHSS scores (5.2 ± 4.2, 4.43 ± 4.28 and 3.9 ± 4.7) at baseline, 3 and 6 months, respectively, in comparison to the medical group with mean NIHSS (4.5 ± 4.2, 11.42 ± 6.3, and 8.5 ± 5.1) and better functional outcome with mean mRS scores (1.3 ± 0.96, 1.2 ± 1.13, and 1.0 ± 1.13) at baseline, 3 and 6 months, respectively, in comparison to the medical group (0.84 ± 0.75, 2.28 ± 1.2, and 2 ± 1.24). TCD assessment of ICAS showed a marked reduction of the percentage of stenosis on 3 months of follow-up among the interventional groups (only 5.6% had > 70% stenosis) in comparison to the medical group (85.7% had > 70% stenosis). Recurrent ischemic events on 6 months of follow-up were 16% among interventional groups in comparison to 84% among medical groups. The mortality rate was 8% among interventional groups due to subarachnoid hemorrhages (SAH) related to procedure in comparison to 28% among medical groups secondary to ischemic events. The intraoperative success rate was 96% with the failure of stent deployment in 1 patient due to the tortuous anatomy of vessels. Early post interventional complication rate, i.e, SAH was 8%. Late post interventional restenosis and occlusion rates were 8% on 3 months of follow-up.

Conclusion

Endovascular stenting of medically refractory ICAS is more efficacious and effective with better clinical and functional outcomes than optimal medical treatment; however, its safety is still debatable.

Trial registration

Done at ClinicalTrials.gov. Trial ID (NCT Number) NCT04393025.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stroke is a leading cause of death globally. Patients surviving a stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) are at an increased risk for subsequent strokes. Without secondary prevention measures, patients after stroke or TIA face an annual risk of 4–16% of serious vascular events [1].

Atherosclerotic intracranial arterial stenosis (ICAS) is one of the most common causes of stroke worldwide and is associated with a high risk of recurrent stroke [2].

Alternative therapies are needed for patients with a recent transient ischemic attack (TIA) or stroke and symptomatic intracranial arterial disease (ICAD), i.e., severe stenosis 70 to 99% of the diameter of a major intracranial artery, because they are at high risk for recurrent stroke in the territory of the stenotic artery (approximately 23% at 1 year) despite aggressive medical treatment and control of vascular risk factors [2, 3].

Medical treatment can reduce the risk of ischemic stroke due to thromboembolic events, but it does not reduce the risk of ICAD progression and the associated pathophysiologic components of poor collateral circulation and hypoperfusion. Successful management of patients with ICAD requires an intervention that is safe, effective, and has minimal complications [4].

Current primary prevention strategies include a combination of lifestyle modification (smoking cessation, dietary intervention, weight loss, and exercise), antihypertensive medications, antithrombotic therapy, and statins [5].

Recommended secondary prevention strategies include a combination of medical therapy and revascularization procedures [5].

Great advances were made in cerebral revascularization techniques in recent years including percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) alone and PTA with stenting (PTAS) using balloon-mounted coronary stents with low 1-year stroke rates following intracranial angioplasty [6].

Restenosis of ICAD remains a possible weakness of primary angioplasty. Symptomatic and angiographic restenosis occur at 6 months in approximately 5–30% of patients treated with angioplasty alone. Re-angioplasty rate was in excess of 20% in one of the most recent studies [7].

Stenting was developed in response to the need for better outcomes after angioplasty and was proven to be effective by reducing the occurrence of plaque dislodgement, intimal dissection, elastic recoil of the vessel wall, and early and late restenosis [8].

A joint position statement by major radiology and neuroradiology societies in October 2005, in alignment with the FDA indication, concluded that balloon angioplasty with or without stenting should be considered in patients who had failed medical therapy [9].

Aim of the work

The aim of the work is to determine the efficacy and safety of angioplasty with stenting in medically refractory ICAS and to compare its effectiveness with optimal medical treatment.

Subjects and methods

Type of study

This is an interventional randomized prospective single-center study.

Study period

The study is carried out during the period from June 2016 to June 2018.

Study place

The study was conducted at El Mataria Teaching Hospital, Cairo, Egypt.

Subjects

Fifty consecutive patients were enrolled, matched, and randomized where twenty-five patients underwent stenting procedures (interventional group) and twenty-five patients received optimal medical treatment without stenting (medical group).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

-

1.

Patients age between 30 and 80 years.

-

2.

Symptomatic ICAS: presented with TIA or stroke, attributed to 70–99% stenosis of a major intracranial artery: internal carotid artery (ICA), middle cerebral artery (MCA) [M1segment], vertebral artery (VA), or basilar artery (BA).

-

3.

Patients with recurrent TIA or stroke despite medical therapy, including anti-coagulation or antiplatelet and control of all vascular risk factors (DM, HTN, and hyperlipidemia).

Exclusion criteria

-

1.

Patients previously stented at the target lesion or had extracranial stenosis.

-

2.

Patient with acute stroke (within 2 weeks from the onset).

-

3.

Complete the occlusion of the artery on the imaging assessment.

-

4.

Massive cerebral infarction (more than half the MCA territory), intracranial hemorrhage, epidural or subdural hemorrhage, and intracranial brain tumor on CT or MRI scans.

-

5.

Contraindications to antithrombotic and/or anticoagulant therapies.

Methods

All patients were subjected to the following:

- 1.

Medical history for risk factors of stroke and history of present illness.

- 2.

Clinical assessment with the National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) and Modified Rankin Scale (mRS) at primary diagnosis, 3 and 6 months after enrollment.

- 3.

Laboratory investigations including complete blood count, liver and renal function tests, prothrombin time (PT), partial thromboplastin time (PTT), blood sugar level HbA1c, and lipid profile.

- 4.

Cardiac assessment with ECG, trans-thoracic echocardiograpy, or trans-esophageal echocardiography as clinically indicated.

- 5.

MRI brain to determine the type of stroke according to Oxfordshire classification.

- 6.

MRA or CTA for intracranial arteries to determine the stenotic artery (ICS).

- 7.

Assessment of intracranial arteries hemodynamic stenosis by TCD mean flow velocity (MFV) at baseline and after 3 months to determine degree and percent of change of ICS after treatment according to Zaho et al.’s criteria (2011) [10].

The medical group treated by the following:

Optimal medical treatment in the form of aspirin (150 mg per day), clopidogrel (75 mg per day) for the duration of follow-up after enrolment.

Management of the primary risk factors (targeting SBP lower than 140 mm Hg (< 130 mm Hg if diabetic) and LDL-C >70 mg/dl, HBA1C > 7%, smoking cessation, weight reduction, and exercise.

The interventional group subjected to the following:

Diagnostic digital subtraction angiography (DSA) to confirm diagnosis and percent of stenosis using “warfarin and aspirin for symptomatic intracranial arterial stenosis trial (WASID) method” where {percent of stenosis = (1-(D stenosis/D normal) × 100} (Samuels et al. 2000) [11].

Interventional angioplasty with stenting in the same session if possible.

All procedures were completely performed by an interventional neurologist.

All intracranial stenting procedures were performed at the interventional neurology unit using (Philipsmachine Allura Fd 20).

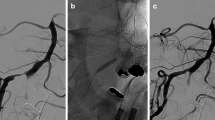

All procedures for the intervention group, i.e, diagnostic and intervention phases, were performed according to the "Stenting and Aggressive Medical Management for Preventing Recurrent stroke in Intracranial Stenosis" (SAMPRISS Trial guidelines) (Chimowitz et al. 2011) [2] (Figs. 1 and 2).

Procedural success was defined as to achieve a < 30% residual diameter stenosis of the treated lesion in at least two matched views on angiography.

Assessment of stented patients for any complications during or after the procedure.

All patients received aspirin 150 mg/day and clopidogrel 75 mg/day for 6 months after the procedure.

Intervention phase after stent deployment of Lt VB stenosis in the same patient in Fig. 1

Follow-up for both groups: clinically by NIHSS & MRS at 3 and 6 months and by TCD at 3 months to assess the percent of stenosis.

Primary endpoint: stroke after 90 days from intervention.

Statistical analysis

-

i.

The collected data was revised, coded, tabulated, and introduced to a PC using Statistical Package for Social Science (IBM Corp. Released 2011. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Data was presented and suitable analysis was done according to the type of data obtained for each parameter.

Descriptive statistics

-

1.

Mean, standard deviation (± SD), and range for parametric numerical data, while the median and interquartile range (IQR) for non-parametric numerical data.

-

2.

Frequency and percentage of non-numerical data.

Analytical statistics

-

1.

Student’s T test was used to assess the statistical significance of the difference between the two study group means.

-

2.

Mann-Whitney test (U test) was used to assess the statistical significance of the difference of a non-parametric variable between two study groups.

-

3.

Chi-square test was used to examine the relationship between two qualitative variables.

-

4.

Fisher’s exact test was used to examine the relationship between two qualitative variables when the expected count is less than 5 in more than 20% of cells.

-

5.

Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to assess the statistical significance of the difference of an ordinal variable (score) measured twice for the same study group.

-

6.

McNemar test was used to assess the statistical significance of the difference between paired qualitative variables.

P value: level of significance

P > 0.05: Non-significant (NS).

P < 0.05: Significant (S).

P < 0.01: Highly significant (HS).

Results

Comparison between intervention and medical groups regarding demographic data and risk factors (RFs)

There was no statistically significant difference between both groups regarding demographic data and RFs for stroke except DM and HTN which were statistically significant more prevalent among intervention group (72.0% and 80.0%), respectively, in comparison to medical group (40.0% and 44.0%) (P value ≤ 0.23 and ≤ 0.009) (Table 1).

Comparison between the intervention group and medical group regarding the types of stroke and site of ICSD

There was no statistically significant difference between both groups regarding radiological type of ischemic stroke according to Oxfordshire classification and arterial site of ICSD (Table 2).

Comparison between the intervention group and medical group as regards NIHSS at baseline, 3 and 6 months after treatment

There was no statistically significant difference between both groups in NIHSS score at baseline. However, there was a highly statistically significant decrease in NIHSS at 3 and 6 months of follow-up among intervention group (4.43 ± 4.28 and 3.91 ± 4.72), respectively, in comparison to medical group (11.42 ± 6.3 and 8.5 ± 5.1) (P value ≤ 0.0001 and ≤ 0.009) (Table 3).

The change of NIHSS shows a statistically significant decrease in NIHSS scores among the interventional group at 3 months of follow-up (17.4%) in comparison to the medical group (8%) with better clinical outcome (P value ≤ 0.002) (Table 4).

Comparison between the intervention group and medical group as regards mRS at baseline, 3 and 6 months after treatment

There was no statistically significant difference between both groups in mRS score at baseline. However, there was a highly statistically significant decrease in mRS score at 3 and 6 months of follow-up among the interventional group (1.22 ± 1.13 and 1.00 ± 1.13), respectively, in comparison to medical group (2.28 ± 1.21 and 2.00 ± 1.24) (P value ≤ 0.004 and ≤ 0.014) (Table 5).

The change of mRS shows a statistically significant decrease in mRS scores among the interventional group at 3 and 6 months of follow-up (17.4% and 26.1%), respectively, in comparison to medical group (4.0% and 16.7%) with the better functional outcome (P value ≤ 0.005 and ≤ 0.005) (Table 6).

Comparison between the intervention and medical group regarding TCD assessment of MFV of ICS at baseline and at 3 months after treatment

There was no statistically significant difference between both groups regarding MFV of the stenotic artery of ICSD at baseline. Yet, a highly statistically significant decrease in MFV among the interventional group (77.94 ± 35.11) on 3 months of follow-up in comparison to the medical group (130.62 ± 25.40) (P value ≤ 0.001) (Table 7 and Fig. 3).

Comparison between the intervention group and medical group as regards the percentage of ICS according to the Zaho criteria at baseline and at 3 months after treatment

There was no statistically significant difference between both groups regarding the percent of stenosis of ICSD at baseline. However, a statistically significant decrease of percent of stenosis of ICSD among interventional groups on 3 months of follow-up (5.9% had > 70% stenosis) in comparison to the medical group (85.7% had > 70% stenosis) (P value ≤ 0.001) (Table 8).

Also, the percent of change in stenosis shows a statistically significant difference between both groups with the increased number of patients who had a significant decrease of percent of stenosis among intervention group (64.7%) with no patient among the medical group (0.0%) who had decreased percent of stenotic ICSD (P value ≤ 0.001) (Table 9 and Fig. 4).

Comparison of clinical outcome after 6 months of follow-up among both groups

There was a statistically significant difference in clinical outcomes between both groups in terms of clinical improvement where 76% of the intervention group showed an improvement in comparison to 16% among the medical group (P value ≤ 0.0001). Regarding recurrent strokes in the stenotic artery territory, only 4 cases (16%) in the intervention group had recurrent large ischemic strokes in comparison to 14 cases (56%) in the medical group (P value ≤ 0.003). Recurrent lacunar infarctions occurred in 5 cases (20%) among the medical group, with no cases among the intervention group (0.0%) (P value ≤ 0.05). The overall mortality rate was higher among the medical group (28%) related to ischemic events from ICSD, in comparison to 8% among the intervention group. yet with no statistically significant difference (Table 10 and Fig. 5).

Discussion

Atherosclerotic intracranial arterial stenosis (ICAS) is one of the most common causes of stroke worldwide and is associated with a high risk of recurrent stroke. Despite aggressive medical treatment and control of vascular risk factors in those patients; however, they are at high risk for recurrent stroke in the stenotic territory. Alternative therapies are needed for those patients with the symptomatic intracranial arterial disease (ICAD), i.e., severe stenosis 70 to 99% of the diameter of a major intracranial artery, with recurrent ischemic events despite optimal medical treatment [2, 3].

Wilson et al. (2014) reported that angioplasty has been used for the treatment of intracranial stenosis [4]. Also, Okada et al. (2015) founded that angioplasty of the lesion may be more essential than bypass surgery in the treatment of the stenotic lesion [6]. Farooq et al. (2014) showed that stenting after angioplasty has proven to be effective by reducing the occurrence of plaque dislodgement, intimal dissection, elastic recoil of the vessel wall, and early and late stenosis [8].

The current study aimed to determine the efficacy and safety of angioplasty with stenting in medically refractory intracranial arterial stenosis.

Fifty patients were randomized 1:1 with 25 patients underwent stenting procedure and 25 patients received optimal medical treatment. The main determinants (age, sex, DM, HTN, dyslipidemia, ISHD, smoking, and degree of stenosis by TCD) were compared between both groups to make sure that both were homogenous with no selection bias. No significant difference between both groups regarding RFs except the HTN and DM which were significantly more prevalent among the intervention group (Table 1).

The current study revealed that males were more prevalent in our cohort (68%) among intervention group and (64%) among the medical group (Table 1) which is in concordance with (Rohde et al. 2013) who found male patients among 62% of self-expandable stent (SES) group and among 87% of balloon-expandable stent (BES) [12].

The current study revealed that the mean age of patients was 58.40 years among intervention versus 60.36 years among the medical group (Table 1) which is younger than patient’s age in the pivotal SAMMPRIS study with a mean age of 61 years among the intervention groups (Chimowitz and The SAMMPRIS Investigators, 2011) [2].

The current study revealed that the transient ischemic attack (TIA) was the most prevalent risk factor (64%) (Table 1). Kasner et al. (2006) found that the risk of subsequent stroke with TIAs depend on the time of event occurred [13].

The current study revealed that hypertension was the second most prevalent RF (60%) (Table 1). Chaturvedi et al. (2007) found that HTN accelerate the progression of atherosclerosis [14]. Turan et al. (2007) found that systolic HTN is an important RF associated with recurrent stroke and ICAS [15].

Diabetes mellitus was the third most prevalent RF in our cohort (56%) (Table 1). Wong and Li (2003) found that DM is the most dependent RF of ICAS [16].

Thirty-two percent of patients had dyslipidemia (Table 1). This was in agreement with the fact that there is a strong relationship between total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and the extent of ICAS atherosclerosis and wall thickness (Qian et al. 2013) [17].

In the current study, 15 cases (30%) had ischemic heart disease (Table 1). In patients with coronary heart disease, the intima-media thickness (IMT) increases in association with myocardial infarction (Meschia et al. 2014) [18].

Regarding the mode of clinical presentation, all cases (100%) had previous symptomatic ischemic strokes related to ICSD. Forty-four percent had previous one ischemic stroke, while 46% had two previous strokes and only 20% had more than two previous strokes in the same stenotic territory despite best medical treatment and vascular RFs control (Table 1). Kasner et al. (2006) found that more than 19% of patients with ICAS developed ischemic stroke in the stenotic territory despite the best medical treatment and vascular RFs control [13].

Regarding the stroke type according to Oxfordshire radiological classification by MRI brain; 26 patients (52%) had posterior circulation infarction, while 12 patients (24%) had partial anterior circulation infarctions and 12 patients ( 24%) had lacunar infarctions (Table 2) which are in agreement with (Rohde et al. 2013) that found posterior circulation infarctions among 60% of its cohort versus 40% in the anterior circulation [12]. However, Jiang et al. (2007) found in their reports that anterior circulation infarctions (59%) were more frequent than posterior circulation (41%) [19].

Regarding the site of the stenotic artery by MRA or CTA, fifty-four percent of patients had basilar stenosis and 8% had MCA stenosis (Table 2) in concomitant with (Rohde et al. 2013) who found that basilar artery stenosis (35%) was more frequent than MCA stenosis (20%) [12]. Yet, Jiang et al. (2007) found that MCA stenosis was more frequent (52%) than basilar artery (22%) and (Marc et al., 2011) also reported the same with MCA stenosis more frequent (45%) than basilar artery stenosis (22%) [2, 19].

Regarding percent of stenosis of ICSD, all patients were assessed by TCD according to (Zaho et al. 2011) criteria [10]. Among intervention group 86.4% of patients had > 70% stenosis and 13.6% had < 70% stenosis. Of the medical group, 83.3% of patients had > 70% stenosis and 16.7% had < 70% stenosis (Table 8).

All intervention group patients were assessed by DSA showing more than 70% stenosis of ICSD. Kasner et al. (2006) reported that severity of ICSD stenosis with > 70% stenosis was highly significant for recurrent stroke in the stenotic territory [13].

We used twenty-one coronary balloon mounted stents and 3 solitaire stents in stenting procedures with a difficult comparison between both groups of stents due to a few number used of solitaire stents.

Regarding clinical assessment by NIHSS, there was no statistically significant difference between both groups in NIHSS score at baseline. However, there was a highly statistically significant decrease in NIHSS at 3 and 6 months of follow-up among intervention group (4.43 ± 4.28 and 3.91 ± 4.72), respectively, in comparison to medical group (11.42 ± 6.3 and 8.5 ± 5.1) (P value ≤ 0.0001 and ≤ 0.009) (Table 3).

Also, the change of NIHSS shows a statistically significant decrease in NIHSS scores among the interventional group at 3 months of follow-up (17.4%) in comparison to the medical group (8%) with better clinical outcome (P value ≤ 0.002) (Table 4).

These findings came in agreement with (Wang et al. 2014) who concluded that NIHSS were worse among patients with ICAS despite the best medical treatment with an increase of the mean NIHSS from 4.6 to 6.6 on follow-up [20]. Yet, Derdeyn et al. (2014) recommended in his study the use of aggressive medical therapy in the treatment of intracranial arterial stenosis [21].

Regarding clinical outcomes by mRS, there was no statistically significant difference between both groups in mRS score at baseline. However, there was a highly statistically significant decrease in mRS score at 3 and 6 months of follow-up among the interventional group (1.22 ± 1.13 and 1.00 ± 1.13), respectively, in comparison to medical group (2.28 ± 1.21 and 2.00 ± 1.24) (P value ≤ 0.004 and ≤ 0.014) (Table 5).

Also, the change of mRS shows a statistically significant decrease in mRS scores among the interventional group at 3 and 6 months of follow-up (17.4% and 26.1%), respectively, in comparison to medical group (4.0% and 16.7%) with the better functional outcome (P value ≤ 0.005 and ≤ 0.005) (Table 6). These results are in concomitant with (Kurre et al. 2008) results who among their interventional cohort had patients improved from mRS score (4) to score (0) [22]. And also in agreement with (Park et al. 2013) who concluded that stenting could improve the outcome of intracranial stenosis [23]. However, in disagreement with (Derdeyn et al. 2014) who recommended aggressive medical therapy in the treatment of ICS [21].

Regarding the efficacy of stenting versus medical treatment by TCD assessment of MFV of ICSD on 3 months of follow-up; our study reported a significant decrease of the mean of MFV among intervention group and significant change of the mean MFV at baseline and at 3 months of follow-up with which highly statistically significant difference (P value ≤ 0.001) (Table 7 and Fig. 3). These results were in agreement with (Kurre et al. 2008) who found a decrease in the mean of MVF after stenting [22].

Regarding the change of percent of stenosis of ICSD by TCD assessment using Zaho criteria, there was no statistically significant difference between both groups regarding the percentage of stenosis of ICSD at baseline. However, a statistically significant decrease of percent of stenosis of ICSD among the interventional group on 3 months of follow-up (5.9% had > 70% stenosis) in comparison to the medical group (85.7% had > 70% stenosis) (P value ≤ 0.001) (Table 8).

Also, the percent of change in stenosis shows a statistically significant difference between both groups with an increased number of patients who had a significant decrease of percent of stenosis among the intervention group (64.7%) with no patient among medical group (0.0%) who had decreased percent of stenotic ICSD (P value ≤ 0.001) (Table 9 and Fig. 4).

Regarding outcome on 6 months of follow-up. Patients who had stenting showed clinical improvement among 76% of its cohort, while worsening occurred among 84% of only medically treated group with (P value ≤ 0.0001) (Table 10). This clinical worsening was attributed to the recurrent stroke in the same stenotic territories of ICSD. These results came in agreement with Chaturvedi et al. (2007) who concluded that IC stenting should be done in patients with medically refractory ICS [14].

Regarding periprocedural (IC stenting) complications of 88% of patients’ passes without any complication related to the procedure and 3 patients (12%) had periprocedural complications. Two of them had perforated stented artery with complicated SAH and eventually died out of this. The third one had basilar artery occlusion by thrombus detachment, but thrombectomy is done in the same session and recanalization and the patient recovered well from anesthesia without any deficit, despite the percent of periprocedural complication in our study is less than reported by (Abruzzo et al. 2007; Fiorella et al. 2007; and Rohde et al. 2013) [12, 24, 25].

Regarding post stenting restenosis and occlusion, one patient had restenosis after stenting and another showed complete occlusion with percent of restenosis of 8%. And this was less than reported by previous studies (Jiang et al. 2007; Zaidat et al. 2008; Derdeyn et al. 2014; and SAMMPRIS) [2, 21, 19, 26] who found the percentage of restenosis of 25%, 12.5%, 19.4%, and 19%, respectively, and more than Levy et al. (2001) and Lee et al. (2005) who had zero percent of restenosis [27, 28].

The success rate in our study was 96% where only one patient had failed stenting procedure due to tortuosity of the blood vessel. This percent was similar to previous studies (Lee et al. 2005 and Zaidat et al. 2008) [26, 28].

Finally, the good outcome results of our study in comparison to previous similar studies particularly the (SAMMPRIS) can be summarized into first, all our participated cases were elective with more than 1 month after the last neurological event even if mild TIAs. Second, we used coronary balloon mounted stent versus wingspan which was used in (SAMMPRIS) and this may be was the main reason of the low number of in stent restenosis (ISR) in our study and a high number in (SAMMPRIS).

Tung et al. (2006) agree with our result and concluded that the use of coronary stent lowered the rate of ISR [29]. Third, the majority of our cases had baseline mRS less than 3 in agreement with Cheng et al. (2016) who concluded that as to preprocedural mRS score, patients with high mRS score (≥ 3) had significantly high rates of in-hospital complication compared with patients with low mRS (< 3) [30]. Fourth, the younger age of our cases in comparison to (SAMMPRIS). Fifth, we did not perform follow-up imaging after 6 months for all patients but for two symptomatic patients only, so in our study, we did not assess asymptomatic restenosis after 6 months. Sixth, the experience of the operators: in SAMMPRIS, a competent neurointerventionalist was required to perform a minimum of 3 Wingspan cases [2].

Conclusion

At the end of this study, we can conclude that elective (after 1 month from the ischemic event) intracranial stenting of symptomatic (> 70% stenosis) ICSD together with optimal medical treatment and vascular risk factor control are superior in efficacy than optimal medical treatment without stenting; however, safety is still debatable.

Recommendations

-

1-

Early detection of intracranial arterial stenosis in clinically suspected patients who are presented with recurrent stroke at the same arterial territory by through TCD and MRA.

-

2-

Regular follow-up to control the vascular risk factors and achievement of an ideal BMI with the encouragement of physical activity to prevent the progression of ICAS.

-

3-

Intracranial stenting should be done in qualified centers with the use of appropriate materials and the presence of an experienced team for management of any complications among patients refractory to the best medical treatment.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zhang Q, Wang C, Zheng M. Li Y, Li J, Zhang L, et al. Aspirin plus clopidogrel as secondary prevention after stroke or transient ischemic attack: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cerebrovasc Dis; 2015; 39: 13-22.

Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Derdeyn CP, Turan TN, Fiorella D, Lane BF. and The SAMMPRIS Trial Investigators. Stenting versus aggressive medical therapy for intracranial arterial stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:993–1003.

Gonzalez NR, Liebeskind DS, Dusick JR, Mayor F, Saver J. Intracranial arterial stenoses: current viewpoints, novel approaches, and surgical perspectives. Neurosurg Rev. 2013;36:175–84.

Wilson TA, Tanweer O, Huang PP, Riina HA. Comparison of outcomes and utilization of extracranial intracranial bypass versus intracranial stenting for intracranial stenosis. Surg Neurol Int. 2014;5:178.

Al Hasan M, Murugan R. Stenting versus aggressive medical therapy for intracranial arterial stenosis: more harm than good. Crit Care. 2012;16(3):310.

Okada H, Terada T, Tanaka Y, Tomura N, Kono K, Yoshimura R, et al. Reappraisal of primary balloon angioplasty without stenting for patients with symptomatic middle cerebral artery stenosis. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2015;55:133–40.

Dumont TM, Kan P, Synder KV, Hopkins LN, Siddiqui AH, Levy EI. Revisiting angioplasty without stenting for symptomatic intracranial atherosclerotic steno-sis after the stenting and aggressive medical management for preventing recur-rent stroke in intracranial stenosis (SAMMPRIS) study. Neurosurgery. 2012;71:1103–10.

Farooq M, Firas A, Jiangyong. Reviving intracranial angioplasty and stenting “SAMMPRIS and beyond”. Front Neurol. 2014;5:1–7.

Gupta A, Desai MM, Kim N, Bulsara KR, Wang Y, Krumholz HM. Trends in intracranial stenting among medicare beneficiaries in the United States, 2006–2010. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2(2).

Zaho L, Barlinn K, Sharma V, Tsivgoulis G, Cava LF, Vasdekis SN, et al. Velocity criteria for intracranial stenosis revisited. Stroke. 2011;42:3429–34.

Samuels OB, Joseph GJ, Lynn MJ, Smith HA, Chimowitz MI. A standardized method for measuring intracranial arterial stenosis. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 2000;21:643–6.

Rohde S, Seckinger J, Hähnel S, Ringleb PA, Bendszus M and Hartmann M. Stent design lowers angiographic but not clinical adverse events in stenting of symptomatic intracranial stenosis – results of a single center study with 100 consecutive patients. Int J Stroke; 2013; Vol 8, February, 87–94.

Kasner S, Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Howlett-Smith H, Stern BJ. Hertzberg VS and The Warfarin Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease (WASID) Trial Investigators. Predictors of ischemic stroke in the territory of a symptomatic intracranial arterial stenosis. Circulation. 2006;113:555–63.

Chaturvedi S, Turan TN, Lynn MJ, Kasner SE, Romano J, Cotsonis G, The WASID Study Group. Risk factor status and vascular events in patients with symptomatic intracranial stenosis. Neurology. 2007;69:2063–8.

Turan TN, Cotsonis G, Lynn MJ, Chaturvedi S, Chimowitz M. and The Warfarin-Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease (WASID) Trial Investigators. Warfarin-Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease (WASID) Trial Investigators. Relationship between blood pressure and stroke recurrence in patients with intracranial arterial stenosis. Circulation. 2007;115:2969–75.

Wong KS, Li H. Long-term mortality and recurrent stroke risk among Chinese stroke patients with predominant intracranial atherosclerosis. Stroke. 2003;34:2361–6.

Qian Y, Pu Y, Liu L, Wang DZ, Zhao X, Wang C, et al. Low HDL-C level is associated with the development of intracranial artery stenosis: analysis from the Chinese intra cranial athero sclerosis (CICAS) study. Plose One. 8(5):e64395. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0064395.

Meschia J, Bushnell C, Boden-Albala B, Braun LT, Bravata DM, Chaturvedi S, et al. Guidelines for the primary prevention of stroke a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association The American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of these guidelines as an educational tool for neurologists. Stroke. 2014;45(12):3754–832.

Jiang WJ, Xu XT, Du B, Dong KH, Jin M, Wang QH, et al. Comparison of elective stenting of severe vs moderate intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis. Neurology. 2007;68:420–6.

Wang Y, Zhao X, Liu L, Soo YO, Pu Y, Pan Y, The CICAS Study Group. Prevalence and outcomes of symptomatic intracranial large artery stenoses and occlusions in China. The Chinese Intracranial Atherosclerosis (CICAS) Study. Stroke. 2014;45:663–9.

Derdeyn CP, Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Fiorella D, Turan TN, Janis LS. and The SAMMPRIS Trial Investigators. Aggressive medical treatment with or without stenting in high-risk patients with intracranial artery stenosis (SAMMPRIS): the final results of a randomised trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9914):333–41.

Kurre W, Berkefeld J, Sitzer M, Neumann-Haefelin T, du Mesnil de Rochemont R. Treatment of symptomatic high-grade intracranial stenoses with the balloon-expandable Pharos stent: initial experience. Neuroradiology. 2008;50:701–8.

Park S, Kim JH, Kwak JK, Baek HJ, Kim BH, Lee DG, et al. Intracranial stenting for severe symptomatic stenosis: self-expandable versus balloon expandable stents. Interv Neuroradiol. 2013;19:276–82.

Abruzzo TA, Tong FC, Waldrop AS, Workman MJ, Cloft HJ, Dion JE. Basilar artery stent angioplasty for symptomatic intracranial atheroocclusive disease: complications and late midterm clinical outcomes. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28:808–15.

Fiorella D, Levy E, Turk AS, Albuquerque FC, Niemann DB, Aagaard-Kienitz B. US multicenter experience with the wingspan stent system for the treatment of intracranial athermanous disease: periprocedural results. Stroke. 2007;38:881–7.

Zaidat O, Klucznik R, Alexander MJ , Chaloupka J, Lutsep H, Barnwell S, et al. The NIH registry on use of the Wingspan stent for symptomatic 70–99% intracranial arterial stenosis. Neurology;2008; 70:1518–1524.

Levy EI, Horowitz MB, Koebbe CJ, Jungreis CC, Pride GL, Dutton K, et al. Transluminal stent-assisted angioplasty of the intracranial vertebrobasilar system for medically refractory, posterior circulation ischemia: early results. Neurosurgery. 2001;48:1215–21.

Lee TH, Kim DH, Lee BH, Kim HJ, Choi CH, Park KP, et al. Preliminary results of endovascular stent-assisted angioplasty for symptomatic middle cerebral artery stenosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26:166–74.

Tung R, Kaul S, Diamond GA, Shah PK. Narrative review: drug-eluting stents for the management of restenosis: a critical appraisal of the evidence. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:913–9.

Cheng L, Jiao L, Gao P, Song G, Chen S, Wang X, et al. Risk factors associated with in-hospital serious adverse events after stenting of severe symptomatic intracranial stenosis. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. 2016;147:59–63.

Funding

No funding body (not applicable).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AMN and AAB proposed the study idea. EA, HA, and MS put the study design. RA collected, analyzed, and interpreted the patient data.MS write the manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All subjects were informed of the general aim of the study, and their participation was fully voluntary. Informed consent had been obtained and approved by the ethics committee for clinical research of the Faculty of Medicine ASU and El Mataria Teaching Hospital (date of ethical approval: 12/6/2016; reference number: FMASU MD 142/2016).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nassef, A.M., Awad, E.M., El-bassiouny, A.A. et al. Endovascular stenting of medically refractory intracranial arterial stenotic (ICAS) disease (clinical and sonographic study). Egypt J Neurol Psychiatry Neurosurg 56, 51 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41983-020-00185-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41983-020-00185-0