Abstract

Background

Several neuropeptides have concerned with epilepsy pathogenesis; ghrelin showed an anticonvulsant effect. There is a potential relation between its level and antiepileptic drug (AEDs) response.

Objective

To evaluate ghrelin effect in adult epileptic patients and in response to AEDs.

Materials and methods

This case control study included 40 adult epileptic patients and 40 healthy controls. Participants were subjected to history taking of seizure semiology, full general and neurological examination, electroencephalography, and cranial imaging. Fasting serum acylated ghrelin (AG), unacylated ghrelin (UAG), and urine AG levels were estimated to all participants by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELIZA).

Results

Serum AG, UAG, and urine AG levels were statistically higher in epileptic patients than controls (p = 0.005, 0.003, and 0.018 respectively). A significant higher level of serum AG was found among generalized epileptic patients (p = 0.038). There was higher statistically significant levels of all measured parameters among poly therapy patients (p = 0.003, 0.013, and 0.001 respectively). Also, a higher statistical significant level of serum AG and UAG in AEDs-responsive patients was found (p < 0.001). Our results demonstrated significant positive correlation between all measured parameters (serum AG, UAG, and urine AG) and epilepsy duration (p = 0.001, 0.002, and 0.009 respectively). High serum AG and UAG levels were independently associated with longer epilepsy duration (p = 0.00 and 0.008) and better response to AEDs (p < 0.001).

Conclusion

These results indicated that serum AG and UAG levels were significantly high in epileptic patients especially with prolonged epilepsy duration and good AEDs response.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03926273 (22-04-2019) “retrospectively registered.”

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Epilepsy is one of the most common chronic neurological diseases. There are about seven million people in the world affected by epilepsy. A number of neuropeptides have been implicated with the pathogenesis of epilepsy [1].

Ghrelin is a 28-amino acid neuropeptide discovered as the endogenous ligand of the growth hormone which stimulates the release of growth hormone by the pituitary gland [2]. There are two major forms of ghrelin in plasma and tissues, acylated ghrelin (AG), and unacylated ghrelin (UAG) [3]. After the secretion of acylated ghrelin, it is quickly desacylated to unacylated ghrelin which is the main circulating peptide as acylation is essential for binding to the growth hormone secretagogue receptor type 1a (GHSR1a) [1].

In the central nervous system (CNS), the main site of ghrelin synthesis is the hypothalamus. The ghrelin receptor GHSR1a is widely expressed, both peripherally and centrally, in seizure-prone regions such as the hippocampus. So, ghrelin may play a role in epilepsy [4, 5].

Studies were performed in animal models of epilepsy ascribed to ghrelin clear antiepileptic properties, though would be somewhat obscure [6]. Several studies observed higher ghrelin levels, but others showed lower levels. This contrasting finding could be based on heterogeneous patient features such as age and antiepileptic treatment, different epilepsy phases, treatment duration, or measurement techniques. Contradictory finding was obtained in pediatric populations, possibly due to the presence of other confounding factors such as the modulation of ghrelin secretion by pubertal stage, age, weight gain, and drug effects [7].

Furthermore, although ghrelin are of utmost interest for patients affected by epilepsy, these peptides have not been well evaluated in adult epileptic patients. For this reason, we evaluated the effect of ghrelin in adult epileptic patients as well as the relation between serum ghrelin levels and the response to antiepileptic drugs (AEDs).

Subjects and methods

The present study was a case control type. All patients were selected from out-patient clinic of Neurology Department, Zagazig University Hospitals, Sharkia Governorate, Egypt, in the period from July 2018 to January 2019.

The study included two groups

Epileptic patients group (group I) consisted of 40 adults (15 females and 25 males), clinically and electrophysiologically diagnosed according to the new international league against epilepsy (ILAE) classification 2017 [8]. Their mean age was 37.6 ± 10.52. They were currently taking AEDs.

Control group (group II) consisted of 40 adults (16 females and 24 males), non-epileptic healthy subjects. They were age, sex, body mass index, and metabolic profile matched with the patients, and their age mean was 38.37 ± 10.46.

Ethical consideration

The study was approved from the institute research board of Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University, Egypt (ZU-IRB#5271\ 2-6-2018). A written consent was taken from all of the participants after explaining the details, benefits as well as risks to them.

Inclusion criteria

All of the participants were included if their age ≥ 18 years. Body mass index (BMI) < 30 kg/m2, total cholesterol < 200 mg/dl, serum triglycerides < 200 mg/dl, and random blood glucose level < 126 mg/dl.

Exclusion criteria

-

1.

Patients with last seizure < 1 week

-

2.

Patients and controls had acute or chronic metabolic disorders (liver, kidney, thyroid, endocrine, or gastrointestinal disorders).

-

3.

Females with irregular menstrual cycle or on estrogen therapy [9].

-

4.

Patients with organic cerebral lesion that was detected on cranial computed tomography (CT) or cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

All participants were subjected to through history taking of seizure semiology, complete general and neurological examination, electroencephalography (EEG), and cranial CT or MRI.

Fasting 4 ml of peripheral blood was collected under complete aseptic conditions (8.00–9.00 AM) from all studied subjects, 2 ml of blood was added in a tube containing protease inhibitor to prevent conversion of acylated ghrelin (AG) to unacylated ghrelin (UAG); the remaining blood sample was collected in a plain vacationer tube for UAG determination; concentrated urine samples were collected from all subjects for AG assessment. AG and UAG levels in blood and concentrated urine were determined by enzyme-linked immune-sorbent assay (ELIZA) using human ghrelin and unacylated ghrelin kits proved by Andy gene biotechnology Co., LTD.

Patients’ samples have obtained ≥ 1 week from the last seizure attack.

Patients group were sub-classified according to response to antiepileptic drugs as drug responsive and drug-resistant group according to the current definition [10].

Statistical analysis

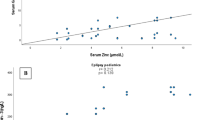

Data were coded and analyzed using statistical package of social science (SPSS version, 22) [11]. Data were expressed as percentage for discrete variables and means (M) ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables student “t” tests, chi-square test, and correlation coefficient (R) were done when appropriate. p value < 0.05 was considered significant and p value < 0.001 was considered highly significant. Logistic regression analysis was used to calculate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for risk estimation. The sensitivity and specificity of serum acylated ghrelin, serum unacylated ghrelin, and urine acylated ghrelin were also assessed by a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (Fig. 1).

We found a significant cutoff > 11.9 pg/ml with sensitivity 81% and specificity 62% for serum AG and > 220 pg/ml with sensitivity > 78% and specificity 60% for serum UAG and > 12.2 pg/ml for urine AG with sensitivity 63.3% and specificity 87.7%.

Results

There was a significant difference between patients and controls as regard serum acylated ghrelin, unacylated ghrelin, and urine acylated ghrelin with the higher levels in the patients groups (p = 0.005, 0.003, and 0.018 respectively) (Table 1).

There were 16 patients presented with focal epilepsy and 24 patients with generalized epilepsy. A significant higher level of serum acylated ghrelin was found among generalized epileptic patients (p = 0.038) (Table 2).

Fifteen patients received one type antiepileptic drug (monotherapy patients) while 25 patients received more than one type of antiepileptic drug (polytherapy patients). There was higher statistically significant levels of all measured parameters among polytherapy patients (p = 0.003, 0.013, and 0.001 respectively) (Table 3).

Splitting patients according to antiepileptic drug (AEDs) response, we found 26 patients were AEDs responsive and 14 patients were AEDs resistant, with a higher statistical significant level of serum acylated ghrelin and unacylated ghrelin in AEDs-responsive patients (p < 0.001) (Table 4).

There were positive correlations between all measured parameters and duration of epilepsy (p = 0.001, 0.002, and 0.009 respectively) (Table 5).

Logistic regression analysis showed that high serum acylated ghrelin was significantly associated with prolonged epilepsy duration (p = 0.00), poly therapy patients (p = 0.021), and AEDs-responsive patients (p = 0.00). High serum unacylated ghrelin was significantly associated with prolonged epilepsy duration (p = 0.008) and AEDs-responsive patients (p = 0.00) (Table 6).

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate ghrelin effect in adult epileptic patients and in response to AEDs. We found that serum acylated ghrelin (AG), unacylated ghrelin (UAG), and urine ghrelin (AG) levels in epileptic patients were statistically higher than controls, those of the similar age, sex, and BMI. This was in accordance of Berilgent and colleagues study [12] who stated higher levels of serum ghrelin regardless type of epilepsy. Others found a significant increase of serum, urine, and saliva levels of AG and UAG in epileptic children [13]. Additionally, the investigators established that enhancement of ghrelin in epilepsy might stimulate the slow-way sleep and prolong non-rapid eye movements (non REM) sleep during the night, in which the seizures have a tendency to occur [12].

Others stated different results as Varrasi and colleagues [14] as they found inter-ictal AG and UAG levels in adult epileptic patients with various epilepsy forms were not altered from those healthy controls.

Conversely, others found a reduction of serum ghrelin levels in epileptic patients before treatment than in controls. They found a reduction in plasma levels of this peptide almost coincident with convulsions [5]. Other studies were done on rates settled a significant decreased of serum acylated ghrelin level post-ictal that could be attributed to its uptake by brain to represent an antiepileptic effect. But reduction of unacylated ghrelin and total ghrelin level failed to range statistical significance [15]. Aydin and colleagues [5] were attributed that AG uptake was increased by CNS structures to modify epileptic discharges so its serum level decrease which was more evident specifically after seizure stimulation. The second clarification is due to diminution of ghrelin to prevent the production of free radicals during seizures.

This contrasting finding could be based on heterogeneous patient features and antiepileptic treatment, different epilepsy phases, or measurement techniques. Contradictory finding that was also obtained in pediatric populations may be attributed to the presence of other additional confounding factors such as the modulation of ghrelin secretion by pubertal stage, age, weight gain, and drug effects [7].

This study showed positive correlations between serums AG, UAG, and urine AG levels and duration of epilepsy. This was stated by Varrasi and colleagues [14] who reported that AG and UAG levels were in direct proportion of epilepsy duration regardless of seizure type, AEDs response, or number of AEDs, which may denote a long-term compensatory mechanism, opposed to the epileptic process. In addition to that, multivariate logistic regression analysis of high laboratory parameters concluded that high AG and UAG levels were significantly associated with prolonged epilepsy duration and AEDs-responsive patients.

This finding was in agreement with others who found higher serum AG and UAG levels in responders to AEDs compared with controls and non-responders and these changes occurred in a way independently on type of AEDs [16]. Also, AG and UAG were downregulated in children affected by refractory epilepsy [17]. That gives the potential role played by these neuropeptides as anticonvulsants; such properties could be linked to epileptic patients and especially intractable seizures [18].

Ge and colleagues [18] supposed the possible mechanisms of ghrelin’s anticonvulsant properties in the subsequent three features: firstly, Ghrelin can reduce cognitive dysfunction in epileptogenesis by endorsing hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Secondly, ghrelin applies anticonvulsant effectiveness via thought-provoking secretion of neuropeptide Y (NPY) which is one of the most studied neuropeptides in epilepsy. NPY is richly expressed in GABAergic interneurons of the central nervous system including the hippocampus. Thirdly, ghrelin exerts neuro-protective and anti-inflammatory belongings and protect neuron from epilepsy-induced neuronal damage.

Conclusion

-

Our results demonstrated significant higher levels of serum AG, UAG, and urine AG in our adult epileptic patients in comparison with controls.

-

These higher serum levels of AG and UAG were significantly independent related with epilepsy duration and better response to AEDs. So, serum levels of AG and UAG could be promising biomarkers of response to AEDs.

Recommendation

-

Further studies are required on larger sample size and longer duration of epilepsy to clarify the precise role of ghrelin at different tissue fluids as antiepileptic neuropeptide that may help to develop new therapeutic ways to epilepsy especially intractable forms.

-

We encourage application of these neuropeptides as a monitor of AEDs response as easy to use to make more rapid and effective decision as well as to avoid additional costs and side effects of AEDs.

Availability of data and materials

Supporting the results of this article are included within the article (and its additional file(s)).

Abbreviations

- AEDs:

-

Antiepileptic drugs

- AG:

-

Acylated ghrelin

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- EEG:

-

Electroencephalography

- ELIZA:

-

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- GHSR1a:

-

Growth hormone secretagogue receptor type 1a

- M:

-

Means

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- NPY:

-

Neuropeptide Y

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SPSS:

-

Statistical package of social science

- UAG:

-

Unacylated ghrelin

- χ 2 :

-

Chi-square

References

Clynen E, Swlysen A, Raiymarkers M, Hoogland G, Rigo JM. Neuropeptides as targets for the development of anticonvulsant drugs. Mol Neurobiol. 2014;50(2):626–46.

Kavac S, Walker MC. Neuropeptides in epilepsy. Neuropeptides. 2013;47(6):467–75.

Banks WA, Tschöp M, Robinson SM, Heiman ML. Extent and direction of ghrelin transport across blood brain barrier is determined by its unique primary structure. J pharmacol Exp ther. 2002;302(2):822–7.

Ferrini F, Salio C, Lossi L, Merighi A. Ghrelin in central neurons. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2009;7:37–49.

Aydin S, Dag E, Ozkan Y, Erman F, Dagli AF, Kilic N, et al. Nesfatin -1 and ghrelin levels in serum and saliva of epileptic patients: hormonal changes can have a major effect on seizure disorders. Mol cell Biochem. 2009;328:40–56.

Portelli J, Threleman I, Ver Donck L, Loyens E, Coppens J, Aourz N, et al. Inactivation of the constitutively active ghrelin receptor attenuates limbic seizure activity in rodents. Neurotherapeutics. 2012;9(3):658–72.

Portelli J, Mrchotte Y, Smoders I. Ghrelin: an emerging new anticonvulsant neuropeptide. Epilepsia. 2012;53(4):585–95.

Fisher RS, Cross JH, French JA, et al. Operational classification of seizure types by the international league against epilepsy: position paper of the ILAE commission for classification and terminology. Epilepsia. 2017;58:522–30.

Kellokoski E, Pöykkö SM, Karjalainen AH, Ukkola O, Heikkinen J, Kesäniemi YA, et al. Estrogen replacement therapy increases plasma ghrelin levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(5):2954–63.

Kwan P, Arzimanoglou A, Berg AT, Brodie MJ, Hauser WA, Mathern G, et al. Definition of drug resistant epilepsy: consensus proposal by the ad hoc task force of the ILAE commission on therapeutic strategies. Epilepsia. 2010;51(6):1069–77.

Levesque R. SPSS programming and data management: a guide for SPSS and SAS users. 4th ed. Chicago: SPSS Inc.; 2007.

Berilgen MS, Mungen B, Ustundag B, Demir C. Serum ghrelin levels are enhanced in patients with epilepsy. Seizure. 2006;16:106–11.

Taskin E, Atli B, Kilic M, Sari Y, Aydin S. Serum, urine and saliva levels of ghrelin and obestatin pre- and post- treatment in pediatric epilepsy. Pediatric neurology. 2014;51(3):365–9.

Varrasi C, Strigaro G, Sola M, Falletta L, Moia S, Prodam F, et al. Interracial ghrelin levels in adult patients with epilepsy. Seizure. 2014;23:852–5.

Ataie Z, Golzar MG, Babri SH, Ebrahimi H, Mohaddes G. Does ghrelin level change after epileptic seizure in rates? Seizure. 2011;20:347–9.

Marchiò M, Roli L, Giordano C, Caramaschi E, Guerra A, Trenti T, et al. High plasma levels of ghrelin and des acyl ghrelin in responders to anti- epileptic drugs. Neurology. 2018;91(1):62–6.

Marchio M, Roli L, Giordano C, Trentic T, Guerrab A, Biagini G. Decreased ghrelin and des-acyl ghrelin plasma levels in patients affected by pharmaco resistant epilepsy and maintained on the ketogenic diet. Clinical nutrition. 2019;38(2):954–7.

Ge T, Yang W, Fan J. Bingjin Li. Preclinical evidence of ghrelin as a therapeutic target in epilepsy. Oncotarget. 2017;8(35):59929–39.

Acknowledgements

The work was carried out in Neurology and Clinical Pathology Departments, Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University, Zagazig, Sharkia, Egypt. The authors acknowledge the subjects for their participation and cooperation in this study.

Funding

There is no source of funding for the research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WM, RN, and HE carried out the work. WM designed the study, coordinated the research team, had done the statistical analysis, and reviewed the manuscript. WM and RN collected the patients, gathered clinical data, and reviewed the manuscript. RN wrote the manuscript, coordinated the research team, and reviewed the manuscript. HE helped the laboratory work of the study. All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved from the institute research board of Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University, Egypt (ZU-IRB#5271\ 2-6-2018). A written consent was taken from all of the participants after explaining the details, benefits as well as risks to them.

Consent for publication

All participants had signed an informed consent to participate and for the data to be published.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Mohamed, W.S., Nageeb, R.S. & Elsaid, H.H. Serum and urine ghrelin in adult epileptic patients. Egypt J Neurol Psychiatry Neurosurg 55, 82 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41983-019-0127-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41983-019-0127-2