Abstract

Background

Pericardial defects are rare anatomical variations that can present as an isolated variation or be associated with other conditions. They are usually asymptomatic and misdiagnosed conditions, and given their rarity, partial pericardial defects can have devastating outcomes. The sudden death of an apparently healthy newborn certainly raises concerns, and a medico-legal investigation is crucial in establishing the cause of death. This case report highlights the importance of awareness on the part of obstetric professionals of the lethal outcomes of pericardial partial congenital defects. This case also demonstrates the difficulty of establishing a correct diagnosis.

Case presentation

The autopsy of a 15-h-old neonate revealed a partial pericardial defect ending in a biventricular strangulation by the defective pericardium. Other findings, such as the patency of the arterial ductus, a subarachnoid hemorrhage, and aspiration of amniotic fluid, were also reported.

Conclusions

Although imaging techniques have evolved, fetal detection of cardiac abnormalities can be tricky, especially when occurring as an isolated variation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The pericardium is a serosal-fibrous double sac surrounding the heart, and its fibrous ligaments enable cardiac stability (Standring et al. 2015). Pericardial defects can be categorized into congenital and acquired. Congenital pericardial malformations are considered rare, with an incidence of < 1 in 10,000–14,000. These defects also present a 3:1 male predominance, and no family link has been reported (Pernot et al. 1972; Yamano et al. 2004; Shah and Kronzon 2015; Rehkämper et al. 2017; Abbas et al. 2005).

The pericardium has various protective and physiological functions. It shields the heart from potential infections from the lungs as well as from mechanical trauma (Cuccuini et al. 2013; Baue and Blakemore 1972). Due to its ligaments, the pericardium maintains the heart’s position inside the thorax, and its fibers prevent overdistensions of the heart. The pericardial fluid reduces the friction of the cardiac surface at the time of systole and diastole (Standring et al. 2015; Shah and Kronzon 2015; Baue and Blakemore 1972; Tubbs and Yacoub 1968).

This case report aims to describe a pericardium variation which led to the sudden death of an apparently healthy newborn. It also highlights the importance of a medico-legal investigation in establishing an unusual cause of death.

Case presentation

This case involves a healthy newborn who died unexpectedly 15 h after delivery. The maternal-fetal medical history specified no pregnancy complications; however, the records report a difficult prolonged labor with a normal vaginal delivery. Although the delivery was difficult, the neonate did not require any intervention or resuscitation maneuvers in the delivery room and was released to the joint accommodation with the parents.

After 5 h, the neonate becomes hypoactive, with reduced reflexes, presenting apnea and a bulging of the fontanelle. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation maneuvers were given as well as orotracheal intubation to little avail. The neonate was pronounced dead 15 h after birth.

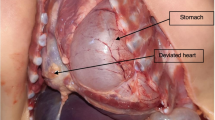

The brain and the heart-lungs block underwent histopathological analysis (see Fig. 1a–c). The results of the post-mortem examination revealed acute hypoxic encephalitis, possibly the result of neonatal brain trauma. Based on the nature of the death, the forensic pathological analysis was carried out revealing a subarachnoid hemorrhage extended to the neural tissue with cerebral intra-parenchymatous hemorrhage as well as the pulmonary aspiration of amniotic fluid. The cardiovascular findings were a patent arterial duct, and the most unsettling finding was a congenital partial pericardial defect leading to a biventricular constriction, confirmed by a histopathological study that showed the partial pericardial defect engendering a biventricular impingement. The histopathological examination also showed a discrete lymphocytic infiltration in the constricted area of the myocardium. Conversely, there was no indication of fibrosis or tissue necrosis. Concerning the coronary vessels, they were preserved, showing no signs of fibrosis or stenosis (see Fig. 1d). The neonate died of unmanageable congestive heart failure 15 h after birth.

Discussion

Congenital pericardial defects can be classified according to the location and whether the absence of the pericardium is complete or partial (Tubbs and Yacoub 1968; Faridah and Julsrud 2002; Centola et al. 2009; Southworth and Stevenson 1938). The most frequent defect is the left side absence of the pericardium while right side defects and complete agenesis are quite rare (Abbas et al. 2005; Southworth and Stevenson 1938). Partial defects are rarer but of clinical importance as they can cause myocardial strangulation and death; however, they are usually asymptomatic or paucisymptomatic (Rehkämper et al. 2017; Centola et al. 2009; Sergio et al. 2019).

The pericardium has a mesodermal embryologic origin which starts around the fourth week of development (Faridah and Julsrud 2002). A common cardinal vein divides into the ventral, originating the pneumopericardium, and the dorsal membranes, where the pleuroperitoneal membrane arises by the fifth week (Moore et al. 2018; Kim et al. 2007). These membranes merge with the medial wall of the pleuroperitoneal canal, then the pleural and pericardial cavities become disconnected. Pericardial defects result as a consequence of the failure of pleuropericardial membranes to fuse entirely or as a failure in its formation (Moore et al. 2018; Kim et al. 2007) as well as the premature atrophy of the left common cardinal vein (Brulotte et al. 2007). These defects are usually left-sided, allowing communication between the pericardial and pleural cavities. More rarely, there can be herniation of the left atrium through the pleural cavity (Moore et al. 2018).

Because most cases are asymptomatic, diagnosis tends to be accidental resulting from imaging studies or surgeries searching for other pathologies or during autopsy procedures, which probably means that its real prevalence is underestimated (Khayata et al. 2020; Parmar et al. 2017; Van Son et al. 1993). Furthermore, most partial congenital aplasia is non-diagnosed and joins the statistics of undefined causes of death. Diagnostics for suspected pericardium defects have evolved with the development of high-definition image studies and protocols designed to identify such embryological anomalies (Faridah and Julsrud 2002; Khayata et al. 2020; Parmar et al. 2017).

Compression and strangulation of adjacent structures including the heart and its parts can happen in partial defects, as in this case report, leading to ischemia, necrosis, and death (Baue and Blakemore 1972; Tubbs and Yacoub 1968; Khayata et al. 2020). The absence of the inferior pericardium is rare in adults (Abbas et al. 2005), maybe due to its incompatibility with life, and can be associated with diaphragmatic defects and herniation of abdominal organs into the pericardial sac (Abbas et al. 2005; Centola et al. 2009).

Congenital pericardial defects are usually found as an isolated variation although they can be associated with other cardiac malformations. Thirty percent of patients have cardiac associated defects, such as a bicuspid aortic valve, persistent ductus arteriosus, an atrial septal defect, or tetralogy of Fallot. It can also be a feature of Cantrell’s pentalogy, which is classically composed of defects in the diaphragmatic pericardium, anterior diaphragmatic hernia, supraumbilical abdominal wall defects, agenesis of the lower sternum, and intracardiac malformation; however, it can present partially with different combinations of these conditions. These malformations can also be associated with genetic syndromes, for example, VACTERL syndrome which leads to several anatomical malformations, among them pericardial defects (Rehkämper et al. 2017; Khayata et al. 2020; Parmar et al. 2017).

There are few articles and case reports showing this condition in newborns, which hinders a clear understanding of the epidemiology of this condition. However, pericardium defects are usually associated with other developmental anomalies which can support early diagnosis as well as prevent devasting outcomes. Prenatal perception of an irregular murmur may be the trigger for initiating further investigations by the obstetrician. Although fetal cardiac ultrasound is good for the detection of complex heart diseases that also involve the pericardium, when isolated, its sensitivity is reduced. Fetal sonography is the most common approach to heart conditions in neonates, but although cardiac defects are the most common congenital defects, the sonographic diagnosis of these conditions is not easy, especially when not associated with other features. The addition of other dimensions (e.g., three- and four-dimensional ultrasounds) can also be helpful in the early detection of pericardium abnormalities (Centola et al. 2009; Sohaey and Zwiebel 1996).

Generally, treatment is not required for congenital pericardium defects; however, prophylactic repair in partial defects is required when herniation occurs or is a threat, and in symptomatic patients needing surgical pericardiectomy, pericardioplasty, primary closure, or others, but for these, diagnosis has to be made before it is too late (Shah and Kronzon 2015; Khayata et al. 2020).

Conclusions

Although imaging techniques have evolved, fetal detection of cardiac abnormalities can be tricky, especially when occurring as an isolated variation.

Availability of data and materials

N/A

Abbreviations

- VACTERL:

-

Vertebral defects, anal atresia, cardiac defects, tracheo-esophageal fistula, renal anomalies, and limb abnormalities

References

Abbas AE, Appleton CP, Liu PT, Sweeney JP (2005) Congenital absence of the pericardium: case presentation and review of literature. Int J Cardiol 98(1):21–25

Baue AE, Blakemore WS (1972) The pericardium. Ann Thorac Surg 14(1):81–106

Brulotte S, Roy L, Larose E (2007) Congenital absence of the pericardium presenting as acute myocardial necrosis. Can J Cardiol 23(11):909–912

Centola M, Longo M, De Marco F, Cremonesi G, Marconi M, Danzi GB (2009) Does echocardiography play a role in the clinical diagnosis of congenital absence of pericardium? A case presentation and a systematic review. J Cardiovasc Med Hagerstown Md 10(9):687–692

Cuccuini M, Lisi F, Consoli A, Mancini S, Bellino V, Galanti G et al (2013) Congenital defects of pericardium: case reports and review of literature. Ital J Anat Embryol 118:136–150

Faridah Y, Julsrud PR (2002) Congenital absence of pericardium revisited. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 18(1):67–73

Khayata M, Alkharabsheh S, Shah NP, Verma BR, Gentry JL, Summers M et al (2020) Case series, contemporary review and imaging guided diagnostic and management approach of congenital pericardial defects. Open Heart 7(1):e001103

Kim JS, Kim HH, Yoon Y (2007) Imaging of pericardial diseases. Clin Radiol 62(7):626–631

Moore KL, Persaud TV, Torchia MG (2018) The developing human: clinically oriented embryology, 11th edn, p 522

Parmar YJ, Shah AB, Poon M, Kronzon I (2017) Congenital abnormalities of the pericardium. Cardiol Clin 35(4):601–614

Pernot C, Hoeffel JC, Frisch R, Henry M, Metz J, Brauer B (1972) Partial aplasia of the pericardium with hernia of the left atrium. Preoperative diagnosis and surgical correction. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss 65(3):397–406

Rehkämper J, Wardelmann E, Müller K-M (2017) Partial pericardium defect with a cardiac heart diverticulum and extensive intrauterine hypoxic myocardial lesions. Pathologe 38(1):45–47

Sergio P, Bertella E, Muri M, Zangrandi I, Ceruti P, Fumagalli F et al (2019) Congenital absence of pericardium: two cases and a comprehensive review of the literature. BJR Case Rep 5(3):20180117

Shah AB, Kronzon I (2015) Congenital defects of the pericardium: a review. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 16(8):821–827

Sohaey R, Zwiebel WJ (1996) The fetal heart: a practical sonographic approach. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 17(1):15–33

Southworth H, Stevenson CS (1938) Congenital defects of the pericardium. Arch Intern Med 61(2):223–240

Standring S, Borley NR, Gray H (2015) Gray’s anatomy: the anatomical basis of clinical practice, 41st edn. Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier, Edinburgh, p 1584

Tubbs OS, Yacoub MH (1968) Congenital pericardial defects. Thorax 23(6):598–607

Van Son JA, Danielson GK, Schaff HV, Mullany CJ, Julsrud PR, Breen JF (1993) Congenital partial and complete absence of the pericardium. Mayo Clin Proc 68(8):743–747

Yamano T, Sawada T, Sakamoto K, Nakamura T, Azuma A, Nakagawa M (2004) Magnetic resonance imaging differentiated partial from complete absence of the left pericardium in a case of leftward displacement of the heart. Circ J Off J Jpn Circ Soc 68(4):385–388

Acknowledgements

N/A

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the report, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PSAP has drafted the work, designed the work, and substantively revised it. LCF has drafted the work and revised it. RT is a forensic pathologist responsible for the forensic analysis and reports. All authors contributed to the final version. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent for publication

Informed consent was obtained from the next of kin of the decedent included in the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de Almeida Prado, P.S., Fernandes, L.C. & Tavares, R. Unexpected death in a newborn due to a congenital partial pericardial defect: a case report. Egypt J Forensic Sci 12, 16 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41935-022-00274-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41935-022-00274-6