Abstract

Background

Scleroderma and adult onset Still’s disease (AOSD) are both uncommon autoimmune disorders. These two disorders have rarely been documented to occur simultaneously. In fact, after a thorough literature review, we discovered only one prior case report in a pregnant individual. Here, we describe the first documented case of scleroderma and AOSD in a postmenopausal patient.

Case presentation

The patient is a 61-year-old Caucasian female with a past medical history significant for peptic ulcer disease, mitral valve prolapse, chronic idiopathic pancreatitis, and limited cutaneous scleroderma with sclerodactyly, Raynaud’s, and calcinosis. She was sent to the emergency room by her primary care physician due to one-week history of intermittent spiking fevers (Tmax 101°F), sore throat, myalgias, arthralgias, and non-pruritic bilateral lower extremity rash. Diagnostic evaluation in the hospital included complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, respiratory viral panel, antinuclear antibody panel, bone marrow biopsy, and imaging with computerized tomography. Our patient fulfilled Yamaguchi Criteria for AOSD and all other possible etiologies were ruled out. She was treated with a steroid taper and methotrexate was initiated on post-discharge day number fourteen. Clinical and biochemical resolution was obtained at three months.

Conclusions

In this report, we describe the first ever documented case of scleroderma and AOSD in a postmenopausal patient. The clinical presentation, diagnostic work up, and management discussed herein may serve as a framework for which rheumatologists and other physicians may draw upon in similar future encounters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Systemic sclerosis, also known as scleroderma, is an uncommon autoimmune disease characterized by cutaneous fibrosis, vascular injury, and organ dysfunction. The etiology of this disorder is thought to be due to dysregulated repair of connective tissue in response to microcellular injury [1]. Two major subgroups exist (limited vs. diffuse) based upon the degree of cutaneous involvement. Patients in the limited subgroup are more prone to distal skin sclerosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, and gastroesophageal reflux [2]. Those in the diffuse subgroup are more likely to experience proximal skin sclerosis and are at greater risk of developing dysfunction of one or more visceral organs (typically renal, cardiac, or pulmonary) [3].

Adult onset Still’s disease (AOSD) is another rare multisystem autoinflammatory disorder. It is characterized by high spiking fever (typically > 102.2°F), arthritis, splenomegaly, and rash. Joint pain is the most common symptom, and is most frequently observed in the wrists, knees, and ankles [4]. Maculopapular ‘salmon’ colored rash occurs in 60–80% of cases and commonly appears on the trunk or proximal limbs [5]. Laboratory analysis typically reveals a neutrophilic leukocytosis with elevated ESR, CRP, and ferritin levels greater than five times the limit of normal. The etiology of this disease is unknown, though infections and malignancies have been implicated as inciting factors [6, 7].

Scleroderma and AOSD are distinct disorders and have rarely been documented to occur simultaneously. The estimated annual incidence is 1.4–5.6 cases per 100,000 individuals for scleroderma and 0.16 cases per 100,000 individuals for AOSD [8, 9]. After a thorough literature review, we discovered only one prior case report of concurrent disease in a pregnant patient [10]. Here, we describe the first ever documented case of limited scleroderma and AOSD occurring together in a postmenopausal female.

Case presentation

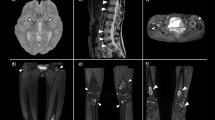

The patient presented to the emergency room with one-week history of sore throat, intermittent spiking fevers, myalgias, arthralgias, and non-pruritic bilateral lower extremity rash. Past medical history was significant for peptic ulcer disease, mitral valve prolapse, chronic idiopathic pancreatitis, and limited cutaneous scleroderma with manifestations of sclerodactyly, Raynaud’s, and calcinosis. Scleroderma had been diagnosed two decades prior. The patient had not been seen by a rheumatologist in four years, however she reported her skin and joint symptoms had been well controlled during this time. On physical exam, the patient was tachycardic (106), with palpable splenomegaly, and also had bilateral knee swelling with limited range of motion. Lab results were remarkable for leukocytosis (22,600) with leftward shift (88% PMNs), abnormal liver function tests—alkaline phosphatase (125), aspartate aminotransferase (50)—and elevated inflammatory markers—Ferritin (20,128), ESR (34), and CRP (206). There was no eosinophilia observed on the complete blood count. CT chest, abdomen and pelvis showed new mediastinal adenopathy and splenomegaly (Figs. 1 and 2). She was admitted to the hospital, and Infectious Disease, Rheumatology, and Hematology were consulted.

While hospitalized, the patient's physical exam evolved from bilateral knee tenderness and swelling to bilateral ulnar wrist tenderness and swelling. X-rays of both wrists showed mild-to-moderate juxta-articular soft tissue swelling with acro-osteolysis (Fig. 3). Further laboratory testing was significant for negative rheumatoid factor, negative cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody, and elevated soluble CD 25 (1,933 pg/mL). The patient underwent a bone marrow biopsy to rule out hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, which showed no evidence of such (Table 1). The patient was given four days of methylprednisone 20 mg as an inpatient, and discharged on a prednisone taper (fourteen days at 20 mg, ten days at 15 mg, fourteen days at 10 mg, 30 days at 5 mg). Methotrexate 12.5 mg weekly was initiated as steroid-sparing therapy on post-discharge day number fourteen. The patient’s symptoms and blood work were monitored closely with near complete resolution, both clinically and biochemically, at three months (Table 2). Liver function tests, specifically alkaline phosphatase and aspartate aminotransferase, had normalized prior to discharge from the hospital. Repeat Chest CT performed at six months demonstrated complete resolution of previous mediastinal adenopathy.

Discussion and conclusion

Our patient had a history of limited scleroderma that was confirmed with positive ANA in a speckled and nucleolar pattern. She was taking pancrealipase for pancreatitis, diltiazem for Raynaud’s, celecoxib for arthralgia, and omeprazole due to her history of peptic ulcer disease. Regarding the patient’s chronic idiopathic pancreatitis, a thorough work up including abdominal imaging, tissue biopsy with histological analysis, and serum IgG levels had been completed at a prior date. There was no evidence to suggest a separate etiology, autoimmune or otherwise, to her recurrent pancreatitis.

The patient’s scleroderma had been controlled when she presented to the hospital with fever, sore throat, myalgias, arthralgias, and evanescent rash. Her symptoms began spontaneously with no preceding febrile illnesses, sick contacts, travel, or outdoor exposures. While AOSD primarily remains a diagnosis of exclusion, most studies utilize the Yamaguchi criteria due to its high sensitivity and specificity [11]. The criteria are fulfilled when a patient demonstrates at least five out of nine possible diagnostic features, with at least two being major criteria. Our patient’s symptoms (arthralgia, non-pruritic rash, and leukocytosis) fulfilled three major criteria per Yamaguchi. Her sore throat, lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, and elevated liver function tests fulfilled four minor criteria. An important caveat to these criteria however, is that the presence of any infection, malignancy, or rheumatic disorder known to mimic AOSD precludes a diagnosis. Our patient’s workup was negative for infectious and malignant etiologies. Furthermore, she did not possess a diagnosis of any rheumatic disease known to mimic AOSD, such as rheumatoid arthritis, reactive arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, polymyositis, or vasculitis. In instances where AOSD is suspected to co-occur with one of these aforementioned disorders, it is important for the clinician to be aware that the Yamaguchi Criteria are not definitive in their ability to rule in or out AOSD. Therefore, physician intuition and special attention to clinical and biochemical clues will be paramount when making an accurate diagnosis.

Management of AOSD has been empirical, with data on treatment efficacy obtained from case reports and retrospective studies. Treatment varies according to disease severity [12]. Mild disease is managed with trial of NSAIDs to control fever and arthralgia. Management for moderate to severe disease is centered on glucocorticoids, with addition of anakinra or tocilizumab once the disease is controlled. Methotrexate can be used in patients with predominantly joint disease.

Development of systemic sclerosis is believed to occur in several distinct phases. The first of these phases is defined by immune mediated damage to vascular endothelial cells, particularly in arterioles [13, 14]. This damage leads to phase two, which is characterized by release of reactive oxygen species and monocytic infiltrate through gaps in endothelial cells into the perivascular space. Macrophages then release IL-8 and TGF-β that promote recruitment of fibroblasts as well as apoptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells [13, 15]. Th2 lymphocytes and CD20 positive B cells stimulate the release of IL-6 [1]. The cumulative effect of these processes leads to phase three, which consists of myofibroblast proliferation and eventual tissue hypoxia.

Less is known regarding the pathophysiology of AOSD. However, the process is thought to occur when a molecular signal, such as a pathogen or malignancy, activates a dysregulated inflammasome [4]. The inflammasome then releases IL-1 and IL-18. IL-18 leads to production of IFNγ, which in turn, increases macrophage activation. Simultaneously, IL-1 serves to recruit neutrophils and additional cytokines (such as IL-8, IL-6, and TNF-α) thereby creating a repetitive cycle of inflammation [4].

Although the clinical manifestations of limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis and AOSD are quite dissimilar, both conditions feature over activation of the innate immune system. In systemic sclerosis, macrophage dependent release of cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-8 contributes to a dysregulated inflammatory cascade that results in fibrosis. In AOSD, overproduction of many of these same cytokines leads to an inflammatory loop that produces symptoms of fever, rash, and joint pain.

In this report, we describe the first documented case of AOSD superimposed upon well-controlled scleroderma in a postmenopausal patient. Our patient presented with a known diagnosis of scleroderma and met seven of the Yamaguchi Criteria for AOSD (including three major criteria). She obtained prompt resolution of her symptoms with the use of glucocorticoids and methotrexate. It is unclear, however, why these two exceedingly rare conditions occurred together in the same individual, though it may suggest a heightened propensity for immune mediated inflammatory diseases in a subset of patients. Future studies may evaluate the potential for shared genetic foci between these, and other autoimmune conditions, with the hope of increasing diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- AOSD:

-

Adult onset Still’s disease

- PMNs:

-

Polymorphonuclear leukocytes

- ESR:

-

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- ANA:

-

Antinuclear antibody

- IgG:

-

Immunoglobulin G

- NSAIDS:

-

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

References

Gabrielli A, Avvedimento EV, Krieg T. Mechanisms of disease-scleroderma. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(19):1989–2003.

van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, et al. Classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American College of Rheumatology/European League against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(11):2737–47.

Jordan S, Maurer B, Toniolo M, et al. Performance of the new ACR/EULAR classification criteria for systemic sclerosis in clinical practice. Rheumatology. 2015;54(8):1454–8.

Gerfaud-Valentin M, Jamilloux Y, Iwaz J, et al. Adult-onset Still’s disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13(7):708–22.

Bagnari V, Colina M, Ciancio G, et al. Adult-onset Still’s disease. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30(7):855–62.

Wouters JM, van der Veen J, van de Putte LB, et al. Adult onset Still’s disease and viral infections. Ann Rheum Dis. 1988;47(9):764–7.

Liozon E, Ly KH, Vidal-Cathala E, et al. Adult-onset Still’s disease as a manifestation of malignancy: report of a patient with melanoma and literature review. Rev Med Interne. 2014;35(1):60–4.

Bergamasco A, Hartmann N, Wallace L, et al. Epidemiology of systemic sclerosis and systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease. Clin Epidemiol. 2019;11:257–73.

Magadur-Joly G, Billaud E, Barrier JH, et al. Epidemiology of adult Still’s disease: estimate of the incidence by a retrospective study in west France. Ann Rheum Dis. 1995;54:587–90.

Plaçais L, Mekinian A, Bornes M, et al. Adult onset Still’s disease occurring during pregnancy: Case-report and literature review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2018;47(4):575–7.

Yamaguchi M, Ohta A, Tsunematsu T, et al. Preliminary criteria for classification of adult Still’s disease. J Rheumatol. 1992;19(3):424–30.

Efthimiou P, Pail PK, Bielory L. Diagnosis and management of adult onset Still’s disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(5):564–72.

Prescott R, Freemont A, Jones C, et al. Sequential dermal microvascular and perivascular changes in the development of scleroderma. J Pathol. 1992;166(3):255–63.

Fleischmajer R, Perlish JS. Capillary alterations in scleroderma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;2(2):161–70.

Kraling BM, Maul GG, Jiminez SA. Mononuclear cell infiltrates in clinically involved skin from patients with systemic sclerosis of recent onset predominantly consists of monocytes/macrophages. Pathobiology. 1995;63(1):48–56.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge those who reviewed the manuscript for their feedback and constructive comments.

Funding

This work did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sector.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JB& DZ conceived the idea of this review article and produced a draft, which was then critically reviewed by BD. The final draft was approved by all co-authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

A signed patient consent form was obtained from the patient prior to submission of this case report.

Competing interests

JB, DZ, and BD report no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Brow, J.D., Zhu, D. & Drevlow, B.E. Adult onset Still’s disease in a patient with scleroderma: case report. BMC Rheumatol 5, 44 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41927-021-00212-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41927-021-00212-4