Abstract

Background

This PET/MRI study compared contrast-enhanced MRI, 18F-FACBC-, and 18F-FDG-PET in the detection of primary central nervous system lymphomas (PCNSL) in patients before and after high-dose methotrexate chemotherapy. Three immunocompetent PCNSL patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma received dynamic 18F-FACBC- and 18F-FDG-PET/MRI at baseline and response assessment. Lesion detection was defined by clinical evaluation of contrast enhanced T1 MRI (ce-MRI) and visual PET tracer uptake. SUVs and tumor-to-background ratios (TBRs) (for 18F-FACBC and 18F-FDG) and time-activity curves (for 18F-FACBC) were assessed.

Results

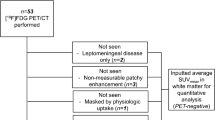

At baseline, seven ce-MRI detected lesions were also detected with 18F-FACBC with high SUVs and TBRs (SUVmax:mean, 4.73, TBRmax: mean, 9.32, SUVpeak: mean, 3.21, TBRpeak:mean: 6.30). High TBR values of 18F-FACBC detected lesions were attributed to low SUVbackground. Baseline 18F-FDG detected six lesions with high SUVs (SUVmax: mean, 13.88). In response scans, two lesions were detected with ce-MRI, while only one was detected with 18F-FACBC. The lesion not detected with 18F-FACBC was a small atypical MRI detected lesion, which may indicate no residual disease, as this patient was still in complete remission 12 months after initial diagnosis. No lesions were detected with 18F-FDG in the response scans.

Conclusions

18F-FACBC provided high tumor contrast, outperforming 18F-FDG in lesion detection at both baseline and in response assessment. 18F-FACBC may be a useful supplement to ce-MRI in PCNSL detection and response assessment, but further studies are required to validate these findings.

Trial registration ClinicalTrials.gov. Registered 15th of June 2017 (Identifier: NCT03188354, https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03188354).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) is a rare extra-nodal non-Hodgkin malignancy making up 4–6% of extra-nodal lymphomas and 3–5% of primary brain tumors (Villano et al. 2011; Tang et al. 2011). PCNSL incidence is increasing, particularly in immunocompetent elderly patients, despite immunodeficiency being the only known risk factor (Shiels et al. 2016). In recent decades, treatment with high-dose methotrexate (HD-MTX)-based chemotherapy, with or without radiation therapy, has been the backbone PCNSL patient management. For eligible patients, induction therapy with polychemotherapy consisting of methotrexate, cytarabine, thiotepa, and rituximab (MATRix) regimen is administered. Additionally, consolidation with either whole-brain irradiation, or high dose chemotherapy supported by autologous stem cell transplantation (HDC/ASCT) has shown excellent long-term outcomes with a 7-years overall survival of 70% (Ferreri et al. 2022). Prognosis is still very poor for patients that are primary refractory, not eligible for HD-MTX treatment, or relapse following initial remission (Houillier et al. 2020).

Pre-treatment (baseline) imaging aims to define disease extent throughout the central nervous system and to exclude concomitant systemic disease. Currently, only brain contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (ce-MRI) is recommended for PCNSL lesion detection (Barajas et al. 2021). Correct treatment requires clinicians to accurately diagnose and distinguish PCNSLs from other brain lesions such as high-grade gliomas (HGG) and brain metastases (BM), which can appear similar with contrast uptake on conventional MRI, due to a common blood brain barrier (BBB) disruption (Okada et al. 2012). Histopathological diagnosis with cytology/flow cytometry of cerebrospinal fluid, or brain biopsy are therefore a pre-treatment necessity. In addition, intermittent and post-treatment response assessment with ce-MRI is essential for determining treatment strategies and achieving optimal patient outcomes.

MRI is a versatile tool which does not expose patients to radiation and provides excellent soft tissue contrast for the delineation of brain lesions. However, conventional MRI has limitations; contrast agents do not cross the intact BBB, treatment related changes are often not discernible from viable tumor tissue, and MRI can be deficient for measuring nuances in the metabolic environment of tumors. The International Primary CNS Lymphoma Collaborative group (IPCG) recommends a PCNSL 3T MRI protocol consisting of several MR sequences (diffusion weighted imaging, contrast enhanced T1 (ce-MRI) and T2, as well as FLAIR and dynamic susceptibility contrast perfusion), and whole-body positron emission tomography (PET) with 18F-2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (18F-FDG) to rule out systemic disease (Barajas et al. 2021). PET has also shown promise in brain tumor detection and diagnosis. The most established PET tracer 18F-FDG can diagnose PCNSLs with high accuracy (Zou et al. 2017). Detection is possible since 18F-FDG is a glucose analogue which accumulates in the highly metabolic PCNSLs, and uptake intensity likely correlates with tumor cell density (Okada et al. 2012). Still, healthy brain tissue has a high baseline glucose consumption, leading to unfavorable 18F-FDG PET brain lesion contrast (Schaller 2004). Functional imaging with brain 18F-FDG PET is therefore not established as standard modality for lesion detection at baseline or to evaluate chemosensitivity and to guide treatment strategies in response assessment in PCNSL in contrast to systemic Hodgkins lymhoma and aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma. There is an increased interest in PET tracers that target other aspects of brain tumor cell biology, such as amino acid PET (AA-PET) tracer uptake which coincides with increased expression of AA transporters in malignant tissue.

Static and dynamic AA-PET has shown great promise in detecting brain tumor malignancy and extent, in some cases allowing for earlier detection of tumor progression and treatment response than MRI (Unterrainer et al. 2016; Galldiks et al. 2013). AA-PET tracers 3,4dihydroxy-6-[18F]-fluoro-l-phenylalanine (18F-FDOPA), [11C]-methyl-methionine (11C-MET), and [18F]-fluoro-ethyltyrosin (18F-FET) are recommended by international guidelines to complement MRI in the evaluation of gliomas (Albert et al. 2016). Nevertheless, the response assessment in Neuro-oncology working group (RANO) does not currently recommend AA-PET for the diagnosis and response assessment of PCNSLs, owing to a scarcity of studies and consequently limited evidence (Barajas et al. 2021).

Thus far, the only AA-PET PCNSL studies with multiple subjects utilize 11C-MET (Okada et al. 2012; Postnov et al. 2022; Jang et al. 2012; Ahn et al. 2018; Kawase et al. 2010; Nomura et al. 2018; Takahashi et al. 2014; Ogawa et al. 1994; Kawai et al. 2010; Miyakita et al. 2020), and there are few published PCNSL cases using 18F-FDOPA and 18F-FET PET (Puranik et al. 2019; Salgues et al. 2021). The aforementioned AA-PET tracers rely primarily on the L-amino-acid-transporter 1 (LAT1) for accumulation in cancerous cells (Heiss et al. 1999; Sun et al. 2018; Habermeier et al. 2015; Ono et al. 2013). 18F-FACBC is another AA-PET tracer that also utilizes LAT1, though it has a higher affinity for the alanine-serine-cysteine transporter 2 (ASCT2) (Ono et al. 2013; Okudaira et al. 2013; Pickel et al. 2020). This feature results in a characteristic low background 18F-FACBC uptake and high lesion contrast, as demonstrated in glioma and BM studies (Tsuyuguchi et al. 2017; Kondo et al. 2016; Wakabayashi et al. 2017; Michaud et al. 2020; Bogsrud et al. 2019; Karlberg et al. 2017, 2019; Johannessen et al. 2021; Parent et al. 2020; Shoup et al. 1999; Øen et al. 2022), nevertheless 18F-FACBC is not yet recommended by international guidelines for the assessment of brain tumors.

The aim of this pilot study was to evaluate the added value of 18F-FACBC and 18F-FDG, as a supplement to standard clinical practice, ce-MRI, in terms of lesion detection at baseline and in response assessment in PCNSL patients. In addition, SUVs were assessed for 18F-FACBC and 18F-FDG, and time-activity curves were assessed for 18F-FACBC.

Methods

Patients

From November 2017 to September 2021 three PCNSL patients newly diagnosed at St. Olav’s hospital, Trondheim University Hospital (Trondheim, Norway) were included in the study (Table 1). Inclusion criteria were immunocompetence, histological confirmed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) based on cytology/flow cytometry of CSF or brain biopsy, age ≥ 18 years, and no previous chemotherapy. Corticosteroid treatment was permitted up to 24 h prior to the PET/MRI examinations.

Study inclusion did not alter routine patient clinical data evaluation and treatment led by experienced oncologists, nuclear medical physicians, and neuroradiologists. All patients gave written informed consent, and the study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics Central Norway (REK, reference number, 2017/325) and the Norwegian Medicines Agency (EudraCT nr: 2017-000306-38).

PET/MRI acquisitions

Patients were examined with 18F-FACBC- and 18F-FDG- PET/MRI (Siemens Biograph mMR, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) on two consecutive days, no more than three days before starting treatment (baseline). Response assessment scans were done 7–14 days after five cycles of treatment with rituximab, HD MTX, procarbazine and vincristine (R-MPV) or 14–21 days after four cycles of MATRix. In response assessment, 18F-FDG PET/MRI was acquired within four days of 18F-FACBC PET/MRI.

18F-FACBC PET/MRI

The MR protocol included T2, DWI, 3D FLAIR, 3D T1 before and after intravenous contrast, and ultra-short echo time (UTE) for attenuation correction of PET data. The patients were required to fast for a minimum of 4 h prior to the injection of 18F-FACBC (mean 220 MBq, range 191–254). The intravenous tracer was injected at t = 0 of a 45-min dynamic PET acquisition. Static PET reconstructions were generated from the last 15 min of the list-mode data, while the dynamic reconstructions were performed with time frames of 12 × 5 s, 6 × 10 s, 6 × 30 s, 5 × 60 s, and 5 × 300 s. PET image reconstruction was performed on the mMR with iterative reconstruction (3D OSEM algorithm, 3 iterations, 21 subsets, 344 × 344 matrix, 4-mm Gaussian filter) with point spread function, decay, and scatter correction. MR-based attenuation correction was performed with a deep learning-based method (DeepUTE) using the ultra-short echo time MR sequence as input for making modified MR-based AC maps (Ladefoged et al. 2020).

18F-FDG PET/MRI

MRI sequences acquired were UTE for attenuation correction of PET data and 3D FLAIR. Patients fasted for minimum 6 h prior to the injection of 18F-FDG (mean 200 MBq, range 178–284) 40-min prior to the start of the PET scan, and a 20-min dynamic/list mode uptake was acquired. Static PET reconstruction was done using the same parameters as for 18F-FACBC and was generated from the whole 20 min uptake.

Clinical image evaluation

Lesion detection was defined separately by clinical evaluations confirming contrast enhanced lesions on MRI and visual assessment of 18F-FACBC and 18F-FDG PCNSL PET tracer uptake by an experienced neuroradiologist (7 years of experience) and a nuclear medicine physician (8 years of experience), respectively.

Static FDG and FACBC analysis

PMOD software (version 4.302, PMOD Technologies LLC, Zürich, Switzerland) was used for analysis of all PET data.

Spherical volumes of interest (VOIs) were placed manually to encompass lesions with visible 18F-FACBC and 18F-FDG tracer uptake to quantify maximum lesion SUVmax in the baseline and response scans.

For 18F-FACBC, an additional 1 ml spherical VOI was auto-generated within lesion tracer uptake regions to calculate peak tracer uptake (SUVpeak), and a crescent shaped VOI was placed on the contralateral side of the brain, to calculate the mean tracer uptake in normal brain tissue (SUVbackground) (Unterrainer et al. 2017) (Fig. 1). For 18F-FACBC, tumor-to-background ratios (TBRmax and TBRpeak) were calculated by dividing SUVmax (or SUVpeak), by SUVbackground.

Dynamic 18 F-FACBC analysis

Spherical VOIs from the static 18F-FACBC analysis were used to generate time-activity-curves (TACs) for SUVbackground, SUVpeak and TBRpeak, according to guidelines (Law et al. 2019). TACs were plotted for 18F-FACBC detected lesions for the entire 45 min of the scan, starting at 22.5 s after injection to avoid noise.

Results

Patient 1

The 81-year-old female patient presented with headache and left side weakness. Brain MRI showed a solitary lesion in the right basal ganglia and neurosurgical biopsy confirmed DLBCL. At baseline, the lesion (P1(B1)) was detected with ce-MRI, with high tracer uptake on both 18F-FDG and 18F-FACBC (Table 2, Fig. 2).

T1 Ce-MRI, fused 18F-FACBC/ce-MRI, and fused 18F-FDG/ce-MRI are shown from left to right. The left and right panel show baseline and response PET/MRI images, respectively. Patients 1–3 (P1–3) are distributed vertically. Scale for ce-MRI was 0–600. Scale for PET detected lesions was SUVbackground − SUVmax. Scale for PET undetected lesions was SUVbackground—SUVmax (baseline lesion uptake). For P3 18F-FDG scans, the lesion was undetected in both scans and the scale used was SUVbackground (mean) − SUVbackground (max)

The patient was treated with five cycles of age-adjusted R-MPV before maintenance with Temozolomide. No lesions were detected in the patient’s ce-MRI, 18F-FDG or 18F-FACBC in the response assessment scans. Recurrence occurred 13 months after the initial diagnoses.

Patient 2

The 75-year-old female patient presented with headache, nausea and personality changes. MRI revealed five lesions (P2(B1–5)) in the white matter in the right cerebral hemisphere (Fig. 2), in addition to a pituitary adenoma which was not included in the study. Biopsy from the right lentiform nucleus revealed DLBCL. All five lymphoma lesions were detected with ce-MRI, 18F-FDG and 18F-FACBC. The small lesion, P2(B4) was difficult to discern with 18F-FDG, though it could be detected with knowledge from MRI and 18F-FACBC images (Table 2). The patient underwent seven cycles of R-MPV before maintenance with Temozolomide.

In the response scan after five cycles, only lesion P2(R4) was detected with ce-MRI and 18F-FACBC, no lesions were detected with 18F-FDG. The patient progressed four months after initial diagnoses.

Patient 3

The 64-year-old male patient presented with dizziness, headache, and cognitive impairment. MRI showed a solitary lesion in the right basal ganglia (Fig. 2). Histology from the neurosurgical biopsy showed DLBCL. At baseline, this small lesion was detected with MRI and 18F-FACBC (P3(B1)), but not 18F-FDG. However, due to recent biopsy it was unclear whether ce-MRI and 18F-FACBC uptake was due to inflammation or malignancy. Due to age and no comorbidity, the patient underwent four cycles of MATRix regime before consolidation with HDC/ASCT.

In the response scan (after four cycles of MATRix), although difficult to distinguish inflammation from malignant tissue, a small lesion was delineated with MRI; the lesion was not detected with 18F-FACBC and 18F-FDG. The patient was still in complete remission one year after the end of treatment.

Static 18 F-FACBC PET/MRI

All seven ce-MRI detected lesions in the baseline scans were also detected with 18F-FACBC, and generally showed high 18F-FACBC SUV and TBR (SUVmax: mean, 4.73; range, 1.03–8.90; TBRmax: mean, 9.32; range, 3.17–16.74; SUVpeak: mean, 3.21; range, 0.68–6.84; TBRpeak:mean, 6.30; range, 2.08–12.87). The high TBR values of 18F-FACBC detected lesions were attributed to consistently low SUVbackground (mean, 0.40; range, 0.21–0.53).

In the response scans, lesions P2(R4) and P3(R1) were detected with ce-MRI, while only one of these lesions (P2(R4)) was detected with 18F-FACBC (SUVmax: 0.97, TBRmax: 2.02, SUVpeak: 0.69, TBRpeak: 1.43).

Static 18 F-FDG PET/MRI

At baseline, the six lesions from P1-2 were detected with 18F-FDG with high tracer uptake (SUVmax: mean, 13.88; range, 8.05–25.09). The solitary ce-MRI and 18F-FACBC detected lesion P3(B1) was not detected with 18F-FDG at baseline.

No lesions were detected with 18F-FDG in the response scans.

Dynamic 18 F-FACBC PET/MRI

TACs for SUVpeak, TBRpeak, and SUVbackground of 18F-FACBC detected lesions are shown in Fig. 3. All TACs had time-to-peak (TTP) within ten minutes. Following TTP, P1(B1), P2(B1), P2(B3), P2(B2), P2(B3), P2(B4), and P2(B5) all had a decreasing TBRpeak curve, whereas P3(B1) and P2(R4) TBRpeak TACs plateaued.

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the use of 18F-FACBC PET/MRI examination compared to 18F-FDG PET/MRI as a supplement to standard clinical practice in patients with PCNSLs, at baseline and for treatment response assessment. This is to our knowledge the first study describing the use of 18F-FACBC in this patient group. The rarity, aggressiveness, and accompanying urgency to start treatment of PCNSLs makes it difficult to design studies with an adequate number of subjects, making the literature on this patient group somewhat limited.

In this study, 18F-FACBC detection correlated with ce-MRI for all lesions, except one small lesion (P3(R1)) on ce-MRI, which could represent inflammation or disrupted BBB. 18F-FACBC outperformed 18F-FDG in the detection of PCNSLs, with higher lesion contrast (Fig. 2 and Table 2). The high 18F-FACBC lesion contrast was a result of a very low 18F-FACBC uptake in normal brain tissue, consistent with findings from previous BM and glioma studies (Tsuyuguchi et al. 2017; Kondo et al. 2016; Wakabayashi et al. 2017; Michaud et al. 2020; Bogsrud et al. 2019; Karlberg et al. 2017, 2019; Johannessen et al. 2021; Parent et al. 2020; Shoup et al. 1999; Øen et al. 2022). This is likely due to slightly different 18F-FACBC transport mechanisms across the BBB compared to other AA-PET tracers. 18F-FET, 11C-MET, and 18F-FACBC all utilize LAT1, however, 18F-FACBC also utilizes and has a higher affinity for ASCT2 (Ono et al. 2013; Okudaira et al. 2013; Pickel et al. 2020). The distribution of the different transport systems may play a critical role in the differences in AA-PET tracer uptake in healthy tissue. ASCT2 transporters are not expressed on the luminal side of the BBB but are expressed on the abluminal side, possibly resulting in increased luminal 18F-FACBC uptake from brain tissue, reducing the tracer concentration in normal brain parenchyma.

The small sample size of this study thwarts the possibility of drawing conclusions with regards to the efficacy of 18F-FACBC compared to 18F-FDG PET/MRI in baseline detection of PCNSLs, though visual assessment of PET tracer uptake revealed that 18F-FACBC produced higher lesion contrast and detected one more lesion (P3(B1)) than 18F-FDG. A meta-analysis pooling 129 immunocompetent PCNSL patients from eight retrospective primary research studies reported high diagnostic accuracy using 18F-FDG, describing a pooled in-patient sensitivity and specificity of 0.88 and 0.86, respectively (Zou et al. 2017). This high sensitivity and specificity of 18F-FDG in PCNSL detection is likely due to PCNSLs having a predilection for localizing in periventricular white matter, and white matter consumes approximately one third of the energy of gray matter (Harris and Attwell 2012). The authors of the meta-analysis conclude that 18F-FDG can be a useful diagnostic tool for PCNSL evaluation, and for discerning between PCNSLs, GBMs and BMs through the use of SUVmax thresholds (Zou et al. 2017); though localised biopsy is still the gold standard for diagnostic confirmation. Static analysis with AA-PET tracers for the detection of PCNSLs may be superior to 18F-FDG, particularly in highly metabolic brain regions, due to a lower SUVbackground and thus higher lesion contrast. Future studies could assess whether 18F-FACBC can be used to distinguish PCNSL malignancy from other tumor types and treatment related changes.

The literature on AA-PET tracer analysis of PCNSLs is very limited, with 11C-MET being the only AA-PET tracer reported in studies with multiple subjects. There have been several studies comparing 11C-MET to 18F-FDG in the evaluation of PCNSLs (Okada et al. 2012; Jang et al. 2012; Kawase et al. 2010; Takahashi et al. 2014; Kawai et al. 2010). Kawase et al. found that although 18F-FDG had higher PCNSL lesion uptake than 11C-MET, both tracers had similar sensitivity for PCNSL detection because there was no significant difference in TBR (Kawase et al. 2010). Additionally, Jang et al. examined the efficacy of 11C-MET PET/CT pre- and post-HD-MTX treatment in four PCNSL patients (Jang et al. 2012). They found that both 18F-FDG and 11C-MET PET/CT demonstrated clear pre-treatment demarcation of PCNSL lesions, though in one patient 11C-MET detected more lesions than 18F-FDG. Jang et al. did not detect any lesions in response scans with PET, though MRI showed non-enhancing T2 hyperintensities in one patient, which was truly indicative of residual DLBCL (Jang et al. 2012). Interestingly, a patient (P3(R1)) in the current study also had an MRI equivocal lesion without 18F-FACBC uptake in response scans, while the patient was still in complete remission one year after end of treatment. In contrast, the patient that had 18F-FACBC uptake in response scans (P2(R4)) progressed four months after initial diagnosis (Fig. 2). This suggests that the absence or presence of 18F-FACBC uptake in lesions could be useful for response assessment and indicate residual PCNSL (Fig. 2).

Studies have shown that the evaluation of dynamic 18F-FET TACs can aid in differentiating low-grade from high-grade gliomas, as well as differentiating radiation necrosis from recurrence in BMs when combining slope curves with TBR (Pöpperl et al. 2007; Romagna et al. 2016; Ceccon et al. 2017; Galldiks et al. 2012). It is however uncertain whether dynamic 18F-FACBC can be utilized for grading gliomas or detecting radiation necrosis, this may be a result of different transport mechanisms utilized by the two tracers (Parent et al. 2020; Øen et al. 2022). With regards to dynamic analysis with 11C-MET, Nomura et al. found that in 31 GBMs and 8 PCNSLs they could with 100% sensitivity and 67.3% specificity distinguish PCNSLs from GBMs, by using a late phase TAC slope coefficient cut-off (Nomura et al. 2018). Okada et al. on the other hand, found that a cut-off of 1.17 in the difference between early- and late-phase SUVmax of dynamic 11C-MET uptake could differentiate perfectly between 15 GBMs and 7 DLBCLs, outperforming a static 18F-FDG SUVmax cut-off which resulted in one false-positive and one false-negative (Okada et al. 2012). In the current study, no conclusions can be drawn from dynamic TAC evaluation, though most lesions had a decreasing TBRpeak and increasing SUVpeak slope, while the two aforementioned studies describe an increasing 11C-MET SUVmax curve in PCNSLs (Okada et al. 2012; Nomura et al. 2018). Studies should be conducted to see whether there is a distinguishable difference between dynamic 18F-FACBC curves of PCNSLs, GBMs, and BMs, which could potentially assist physicians in diagnostic assessment.

An advantage of this study is that it shows the utility of simultaneous PET/MRI for neuroimaging. It provides neuroradiologists, nuclear medicine physicians, and oncologists with information from a single examination without the need to perform image registration, and the different image modalities are acquired under the same biological conditions. Despite being the first study to describe the use of 18F-FACBC in patients with PCNSLs, there are some clear limitations to this study. The evaluation of PET and MRI images was not blinded, which could have influenced PET image analysis—particularly for 18F-FDG images which had more tracer uptake in general. The sample size was small, resulting in a more descriptive than quantitative report. Although 5–10 patients were planned to be included in this study, there are several reasons why only three were included. Technical problems with the airplane transporting 18F-FACBC from Oslo to Trondheim resulted in cancellations, and study inclusion was impeded by production problems at the cyclotron lasting from October 2021 until the end of the inclusion period in December 2022. Finally, the rarity of PCNSL occurrence in addition to covid and the limitations mentioned above resulted in only three patients being included in the planned project period.

Conclusions

18F-FACBC consistently provided high lesion contrast for all PET detected PCNSLs, outperforming 18F-FDG in the detection of PCNSLs at baseline and in response evaluation. High 18F-FACBC TBR values are caused by low tracer uptake in normal brain tissue—a well-established attribute which makes 18F-FACBC unique among AA-PET tracers. The only lesion not visually detected with 18F-FACBC was a small lesion which appeared atypical on ce-MRI, this could have indicated the absence of residual PCNSL as this patient was still in complete remission one year after end of treatment. Ultimately, 18F-FACBC may be useful as a supplement to ce-MRI in the assessment of PCNSLs, particularly for response assessment, though further studies with more subjects are required to validate these findings.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the European Union General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR), but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- PCNSL:

-

Primary central nervous system lymphomas

- HD-MTX:

-

High-dose methotrexate

- ce-MRI:

-

Contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging

- TBRs:

-

Tumor-to-background ratios

- HGG:

-

High-grade gliomas

- BM:

-

Brain metastases

- BBB:

-

Blood brain barrier

- IPCG:

-

International Primary CNS Lymphoma Collaborative group

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

- 18F-FDG:

-

18F-2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose

- AA-PET:

-

Amino acid PET

- 18F-FDOPA:

-

3,4-Dihydroxy-6-[18F]-fluoro-L-phenylalanine

- 11C-MET:

-

[11C]-methyl-methionine

- 18F-FET:

-

[18F]-fluoro-ethyltyrosin

- RANO:

-

Neuro-oncology working group

- LAT1:

-

L-Amino-acid-transporter 1

- ASCT2:

-

Alanine–serine–cysteine transporter 2

- DLBCL:

-

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

- R-MPV:

-

Rituximab, methotrexate, procarbazine and vincristine

- MATRix:

-

Methotrexate, cytarabine, rituximab, thiotepa

- BCNU ASCT:

-

Carmustine–thiotepa-conditioned autologous stem cell transplantation

- IELSG score:

-

International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group score

- MSKCC score:

-

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center score

- ECOG PS:

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance scale

- UTE:

-

Ultra-short echo time

- VOIs:

-

Volumes of interest

- TACs:

-

Time activity curves

- TTP:

-

Time-to-peak

References

Ahn SY, Kwon SY, Jung SH et al (2018) Prognostic significance of interim 11C-methionine PET/CT in primary central nervous system lymphoma. Clin Nucl Med 43:e259–e264

Albert NL, Weller M, Suchorska B et al (2016) Response assessment in neuro-oncology working group and European association for neuro-oncology recommendations for the clinical use of PET imaging in gliomas. Neuro Oncol 18:1199–1208

Barajas RF, Politi LS, Anzalone N et al (2021) Consensus recommendations for MRI and PET imaging of primary central nervous system lymphoma: guideline statement from the International Primary CNS Lymphoma Collaborative Group (IPCG). Neuro Oncol 23:1056–1071

Bogsrud TV, Londalen A, Brandal P et al (2019) 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT in suspected residual or recurrent high-grade glioma. Clin Nucl Med 44:605–611

Ceccon G, Lohmann P, Stoffels G et al (2017) Dynamic O-(2–18F-fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine positron emission tomography differentiates brain metastasis recurrence from radiation injury after radiotherapy. Neuro Oncol 19:281–288

Ferreri AJM, Cwynarski K, Pulczynski E et al (2022) Long-term efficacy, safety and neurotolerability of MATRix regimen followed by autologous transplant in primary CNS lymphoma: 7-year results of the IELSG32 randomized trial. Leukemia 36:1870–1878

Galldiks N, Stoffels G, Filss CP et al (2012) Role of O-(2–18F-fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine PET for differentiation of local recurrent brain metastasis from radiation necrosis. J Nucl Med 53:1367–1374

Galldiks N, Rapp M, Stoffels G et al (2013) Earlier diagnosis of progressive disease during bevacizumab treatment using O-(2–18F-fluorethyl)-L-tyrosine positron emission tomography in comparison with magnetic resonance imaging. Mol Imaging 12:273–276

Habermeier A, Graf J, Sandhöfer BF et al (2015) System l amino acid transporter LAT1 accumulates O-(2-fluoroethyl)-l-tyrosine (FET). Amino Acids 47:335–344

Harris JJ, Attwell D (2012) The energetics of CNS white matter. J Neurosci 32:356–371

Heiss P, Mayer S, Herz M et al (1999) Investigation of transport mechanism and uptake kinetics of O-(2- [18F]fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine in vitro and in vivo. J Nucl Med 40:1367–1373

Houillier C, Soussain C, Ghesquieres H et al (2020) Management and outcome of primary CNS lymphoma in the modern era: an LOC network study. Neurology 94:e1027–e1039

Jang S, Lee K, Lee K et al (2012) 11C-methionine PET/CT and MRI of primary central nervous system diffuse large B-cell lymphoma before and after high-dose methotrexate. Clin Nucl Med 37:e241–e244

Johannessen K, Berntsen EM, Johansen H et al (2021) 18F-FACBC PET/MRI in the evaluation of human brain metastases: a case report. Eur J Hybrid Imaging 5:7

Karlberg A, Berntsen EM, Johansen H et al (2017) Multimodal 18F-fluciclovine PET/MRI and ultrasound-guided neurosurgery of an anaplastic oligodendroglioma. World Neurosurg 108:989.e1-989.e8

Karlberg A, Berntsen EM, Johansen H et al (2019) 18F-FACBC PET/MRI in diagnostic assessment and neurosurgery of gliomas. Clin Nucl Med 44:550–559

Kawai N, Okubo S, Miyake K et al (2010) Use of PET in the diagnosis of primary CNS lymphoma in patients with atypical MR findings. Ann Nucl Med 24:335–343

Kawase Y, Yamamoto Y, Kameyama R et al (2010) Comparison of 11C-methionine PET and 18F-FDG PET in patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma. Mol Imaging Biol 13:1–6

Kondo A, Ishii H, Aoki S et al (2016) Phase IIa clinical study of [18F]fluciclovine: efficacy and safety of a new PET tracer for brain tumors. Ann Nucl Med 30:608–618

Ladefoged CN, Hansen AE, Henriksen OM et al (2020) AI-driven attenuation correction for brain PET/MRI: clinical evaluation of a dementia cohort and importance of the training group size. Neuroimage 222:117221

Law I, Albert NL, Arbizu J et al (2019) Joint EANM/EANO/RANO practice guidelines/SNMMI procedure standards for imaging of gliomas using PET with radiolabelled amino acids and [18 F]FDG: version 1.0. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 46:540–557

Michaud L, Beattie BJ, Akhurst T et al (2020) F-Fluciclovine (18 F-FACBC ) PET imaging of recurrent brain tumors. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 47:1353–1367

Miyakita Y, Ohno M, Takahashi M et al (2020) Usefulness of carbon-11-labeled methionine positron-emission tomography for assessing the treatment response of primary central nervous system lymphoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol 50:512–518

Nomura Y, Asano Y, Shinoda J et al (2018) Characteristics of time-activity curves obtained from dynamic 11C-methionine PET in common primary brain tumors. J Neurooncol 138:649–658

Øen SK, Johannessen K, Pedersen LK et al (2022) Diagnostic value of 18 F-FACBC PET / MRI in brain metastases. Clin Nucl Med. https://doi.org/10.1097/RLU.0000000000004435

Ogawa T, Kanno I, Hatazawa J et al (1994) Methionine PET for follow-up of radiation therapy of primary lymphoma of the brain. Radiographics 14:101–110

Okada Y, Nihashi T, Fujii M et al (2012) Differentiation of newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme and intracranial diffuse large B-cell lymphoma using 11c-methionine and 18f-FDG PET. Clin Nucl Med 37:843–849

Okudaira H, Nakanishi T, Oka S et al (2015) Corrigendum to Kinetic analyses of trans-1-amino-3-[18F]fluorocyclobutanecarboxylic acid transport in Xenopus laevis oocytes expressing human ASCT2 and SNAT2 [Nucl. Med. Biol, 2013, 40, 670–675]. Nucl Med Biol 42:513–514

Ono M, Oka S, Okudaira H et al (2013) Comparative evaluation of transport mechanisms of trans-1-amino-3-[18F]fluorocyclobutanecarboxylic acid and l-[methyl- 11C]methionine in human glioma cell lines. Brain Res 1535:24–37

Parent EE, Patel D, Nye JA et al (2020) [18F]-Fluciclovine PET discrimination of recurrent intracranial metastatic disease from radiation necrosis. EJNMMI Res 10:1–9

Pickel TC, Voll RJ, Yu W et al (2020) Synthesis, radiolabeling, and biological evaluation of the cis stereoisomers of 1-amino-3-fluoro-4-(fluoro-18F)cyclopentane-1-carboxylic acid as PET imaging agents. J Med Chem 63:12008–12022

Pöpperl G, Kreth FW, Mehrkens JH et al (2007) FET PET for the evaluation of untreated gliomas: correlation of FET uptake and uptake kinetics with tumour grading. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 34:1933–1942

Postnov A, Toutain J, Pronin I et al (2022) First-in-man noninvasive initial diagnostic approach of primary CNS lymphoma versus glioblastoma using PET With 18F-Fludarabine and l-[methyl-11C]Methionine. Clin Nucl Med 47:699–706

Puranik AD, Boon M, Purandare N et al (2019) Utility of FET-PET in detecting high-grade gliomas presenting with equivocal MR imaging features. World J Nucl Med 18:266–272

Romagna A, Unterrainer M, Schmid-Tannwald C et al (2016) Suspected recurrence of brain metastases after focused high dose radiotherapy: can [18F]FET- PET overcome diagnostic uncertainties? Radiat Oncol 11:1–10

Salgues B, Kaphan E, Molines E et al (2021) High 18F-FDOPA PET uptake in primary central nervous system lymphoma. Clin Nucl Med 46:E59–E60

Schaller B (2004) Usefulness of positron emission tomography in diagnosis and treatment follow-up of brain tumors. Neurobiol Dis 15:437–448

Shiels MS, Pfeiffer RM, Besson C et al (2016) Trends in primary central nervous system lymphoma incidence and survival in the U.S. Br J Haematol 174:417–424

Shoup TM, Olson J, Hoffman JM et al (1999) Synthesis and evaluation of [18F]1-amino-3-fluorocyclobutane- 1- carboxylic acid to image brain tumors. J Nucl Med 40:331–338

Sun A, Liu X, Tang G (2018) Carbon-11 and fluorine-18 labeled amino acid tracers for positron emission tomography imaging of tumors. Front Chem 5:1–16

Takahashi Y, Akahane T, Yamamoto D et al (2014) Correlation between positron emission tomography findings and glucose transporter 1, 3 and L-type amino acid transporter 1 mRNA expression in primary central nervous system lymphomas. Mol Clin Oncol 2:525–529

Tang YZ, Booth TC, Bhogal P et al (2011) Imaging of primary central nervous system lymphoma. Clin Radiol 66:768–777

Tsuyuguchi N, Terakawa Y, Uda T et al (2017) Diagnosis of brain tumors using amino acid transport PET imaging with 18F-fluciclovine: a comparative study with l-methyl-11c-methionine PET imaging. Asia Ocean J Nucl Med Biol 5:85–94

Unterrainer M, Schweisthal F, Suchorska B et al (2016) Serial 18F-FET PET imaging of primarily 18F-FET-negative glioma: does it make sense? J Nucl Med 57:1177–1182

Unterrainer M, Vettermann F, Brendel M et al (2017) Towards standardization of18F-FET PET imaging: do we need a consistent method of background activity assessment? EJNMMI Res EJNMMI Res 7:1–8

Villano JL, Koshy M, Shaikh H et al (2011) Age, gender, and racial differences in incidence and survival in primary CNS lymphoma. Br J Cancer 105:1414–1418

Wakabayashi T, Iuchi T, Tsuyuguchi N et al (2017) Diagnostic performance and safety of positron emission tomography using 18F-fluciclovine in patients with clinically suspected high- or low-grade gliomas: a multicenter phase IIb trial. Asia Ocean J Nucl Med Biol 5:10–21

Zou Y, Tong J, Leng H et al (2017) Diagnostic value of using 18F-FDG PET and PET/CT in immunocompetent patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget 8:41518–41528

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the radiographers at the PET centre at the Department of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine at St. Olavs University hospital, Trondheim, Norway, for their valuable assistance throughout the project.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Norwegian University of Science and Technology The study was funded by the Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TH was responsible for the study design, acquisition protocols and patient recruitment, assisted with ethical approvals and draftet the manuscript. KJ was responsible for the analyses and draftet the manuscript together with TH. EMB interpreted the MRI images and revised the paper critically. HJ interpreted the PET images and revised the paper critically. GFG assisted and advised on the statistical analyses and revised the paper critically. AK assisted with the PET analyses and critically reviewed the paper. UMF participated in the study design, patient recruitment and revised the paper critically. LE participated in the study design and acquisition protocols, applied for ethical approvals, helped to draft the manuscript and revised it critically. All authors have read and approved the attached paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics Central Norway (REK, reference number, 2017/325). Written informed consent was obtained from the participants. All methods and analysis have been performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Declared consent for publication not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Husby, T., Johannessen, K., Berntsen, E.M. et al. 18F-FACBC and 18F-FDG PET/MRI in the evaluation of 3 patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma: a pilot study. EJNMMI Rep. 8, 2 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41824-024-00189-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41824-024-00189-6