Abstract

Background

The Good Life with osteoArthritis: Denmark (GLA:D™), an evidence-based education and exercise program designed for conservative management of knee and hip osteoarthritis (OA), has been shown to benefit participants by reducing pain, improving function, and quality of life. Standardized reporting in the GLA:D databases enabled the measurement of self-reported and performance-based outcomes. There is a paucity of qualitative research on the participants’ perceptions of this program, and it is important to understand whether participants’ perceptions of the benefits of the program align with reported quantitative findings.

Methods

We conducted semi-structured telephone interviews with individuals who participated in the GLA:D program from January 2017 to December 2018 in Alberta, Canada. Data were analyzed using an interpretive description approach and thematic analysis to identify emergent themes and sub-themes associated with participants perceived benefits of the GLA:D program. We analyzed the data using NVivo Pro software. Member checking and bracketing were used to ensure the rigour of the analysis.

Results

30 participants were interviewed (70% female, 57% rural, 73% knee OA). Most participants felt the program positively benefited them. Two themes emerged from the analysis: wellness and self-efficacy. Participants felt the program benefited their wellness, particularly with regard to pain relief, and improvements in mobility, strength, and overall well-being. Participants felt the program benefited them by promoting a sense of self-efficacy through improving the confidence to perform exercise and routine activities, as well as awareness, and motivation to manage their OA symptoms. Twenty percent of participants felt no benefits from the program due to experiencing increased pain and feeling their OA was too severe to participate.

Discussion

The GLA:D program was viewed as beneficial to most participants, this study also identified factors (e.g., severe OA, extreme pain) as to why some participants did not experience meaningful improvements. Early intervention with the GLA:D program prior to individuals experiencing severe OA could help increase the number of participants who experience benefits from their participation.

Conclusion

As the GLA:D program expands across jurisdictions, providers of the program may consider recruitment earlier in disease progression and targeting those with mild and moderate OA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a degenerative joint condition associated with pain, functional limitations, and stiffness that impacts physical activity, work participation, mental health, and quality of life [1,2,3,4,5]. Evidence-based guidelines recommend treating OA using non-operative treatments such as education, exercise, and weight management as the first-line approach to managing hip and knee OA symptoms [6]. Despite the evidence supporting first-line approaches, studies consistently report a lack of uptake of these recommendations for a significant number of patients [7,8,9].

The Good Life with osteoArthritis: Denmark (GLA:D™) is an evidence-based program for symptomatic hip and knee OA that consists of 12 supervised neuromuscular group exercise classes held twice a week for 6-weeks, along with two structured education sessions [10,11,12,13,14]. The GLA:D program has been implemented in multiple countries including Australia, Austria, Canada, China, New Zealand, and Switzerland [15]. In Canada, as of 2022, the GLA:D program had been implemented in all 10 provinces and 2 of 3 territories [16].

Previous studies have demonstrated the GLA:D program’s effectiveness in reducing pain, improving quality of life, enhancing self-efficacy, and delaying joint replacement surgery among adults with moderate to severe hip or knee OA [12,13,14,15]. There has been limited work published on the qualitatively assessed experiences of individuals with hip and knee OA participating in the GLA:D program [17, 18]. Our previous work found the GLA:D program to be acceptable to participants and had a positive impact on a patient’s physical health routines and quality of life [19]. Ezzat et al. [18] found similarly positive experiences of the program in virtual as well as in-person delivery models.

Although patient-reported outcomes are captured using validated measurement tools, to our knowledge, no studies have focused on qualitatively exploring patient perceptions of the outcomes of the GLA:D program. Our study aims to fill this gap by examining how program participants perceived the benefits, or lack thereof, of the GLA:D program. Moreover, our study aims to supplement existing quantitative participant-reported outcomes from GLA:D Canada [20] to provide a contextual lens to the impact of GLA:D on daily routines, self-management approaches, and beliefs and attitudes towards exercise or physical activity. By pairing quantitative outcomes with the lived experiences of participants, we gain a richer understanding of the benefits, and potential drawbacks, of the program among people living with knee and/or hip OA. This contextual information is crucial to better understand and address potential barriers or challenges to implementation.

Methods

Study design

This study is a part of an overall evaluation of the province-wide implementation and spread of the GLA:D program in Alberta, Canada, informed by the RE-AIM framework [21]. This larger evaluation project had multiple objectives and companion papers focused on provider experiences in implementing the GLA:D program [22] and patient experience with the program [19]. We employed Thorne et al.’s [23] interpretive description approach to this qualitative inquiry. Reporting in this study is in alignment with the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist [24] (see Additional File 1). Ethical approval was obtained from the Health Research Ethics Review Board at the [blinded for review] (Pro00068308).

Study setting

The evaluation was conducted in Alberta, Canada, the fourth largest province in Canada with a population of approximately 4.4 million, 50% of whom live in two metropolitan cities: Calgary and Edmonton [25]. Alberta has a single-payer public healthcare system which primarily covers physician-based services and hospital-based care. Limited public funding is available for rehabilitation services (e.g., physical therapy, occupational therapy); however, private rehabilitation services are also available [26].

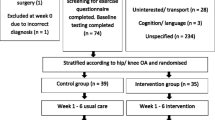

Participant selection

We employed a purposive sampling strategy to generate a diverse sample of individuals who participated in the GLA:D program. The sampling aimed to maximize variation across geography, clinical settings, and gender. Participants were included if they met three criteria: (1) aged 18 years or older, (2) living with symptomatic hip or knee OA, and (3) attended at least one of the GLA:D program sessions between January 2017 and December 2018 in Alberta. Recruitment occurred in nine clinics from the initial cohort of 12 clinics that implemented the GLA:D program in 2017. These clinics included both public healthcare centers and private clinical settings that were located in rural (n = 17) and urban or metropolitan areas (n = 13) [27]. From these clinics, 96 participants consented to be contacted. Of those who consented to be contacted, 12 provided incorrect contact information, 51 were unable to be contacted after attempts, and 33 participants were successfully contacted.

Data collection

We conducted semi-structured telephone interviews with participants, on average, four months (ranging from 1 month to 12 months) after completion of the GLA:D program. Informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to the interview. Interviews were guided by a semi-structured interview guide (see Additional File 2). Data collection ended when no new insights were generated through subsequent interviews, as determined by consensus during the analysis process (i.e., data saturation) [28].

Data analysis

All interviews were conducted by two research team members (AKR and EM) and were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim, and de-identified for analysis. NVivo Pro12 software was used to support data management and the analytic process. Interviews lasted between 20 to 60 minutes. A thematic analysis approach was employed, which was initiated with the development of descriptive codes and categories. Two researchers (DT and AKR) independently conducted initial data coding and established agreement on code categories and data interpretation. Descriptive analysis was followed by an interpretive analysis, where the researchers clustered and re-clustered descriptive categories to inductively identify emergent themes and sub-themes. Emergent themes were validated by a third researcher and reviewed by three research team members (LB, AJ, and GJP) to confirm logical presentation and alignment with the study objective. To enhance the quality of the analytic output, a code-recode strategy was used whereby coders undertook repetitive analyses of data segments, comparing their own coding for consistency, and further refinement of emergent categories. Regular meetings were held to discuss the emerging findings and personal reflections that enabled team members to unpack their potential biases and perspectives about the findings. A description of the research team members’ backgrounds is provided in Additional File 3.

Results

Thirty participants completed the interview. Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. The majority of those interviewed were female (70%), living in rural settings (57%), participating in a publicly covered GLA:D program (80%), living with knee OA (73%), and participated in physical activity before beginning the GLA:D program (63%). Regarding program attendance, 60% of our sample reported completing the program without missing any classes and 17% did not complete the program.

Themes

Most participants (77%) described some level of benefit from their participation in the GLA:D program. Approximately a quarter of the participants (23%) perceived no benefits at all from their participation due to persistent and/or exacerbated pain and their perceived severity of OA. Of those who found the program beneficial, less than one-third (27%) only perceived limited benefits from the GLA:D program, citing reasons such as a failure to meet their anticipated goals and a lack of overall improvement. Two themes emerged that encapsulate the perceived benefits of GLA:D from the participant’s point of view: Wellness and Self-Efficacy.

Wellness

The majority of participants (77%) identified that the GLA:D program had a positive impact on their health and well-being, albeit to varying degrees. Three emergent categories illustrated the improved wellness experienced by participants: (1) pain reduction and management, (2) improved mobility, and (3) improved strength. Selected quotes are referenced in this section, with the remaining quotes presented in Table 2.

Pain reduction and management

For some participants, the GLA:D program was an effective way of addressing their OA-associated joint pain. Over one-third (37%) of the participants reported pain reduction and three participants even reported being pain-free after completing the program. Many recognized that they needed to continue with the GLA:D exercises after program completion to effectively continue to manage their pain; the exercises provided a mechanism by which to manage their pain more effectively and independently. The relationship between the exercises and pain is reflected in the experience of Participant 21:

…… it improved, my knee. If it was sore and I did the exercises… it seemed like the exercises would take the soreness out of my knee. (Participant 21)

The connection between proper joint alignment and pain was also made, resulting in a greater focus on quality of movement. As explained by Participant 5:

…that whole idea of the mechanics of, of your movements. That kind of helped me,… if I’m finding that I have pain on a set of stairs, if I go and do it the next time, thinking about you know, engaging my glutes, my core and that type of thing, right? (Participant 5)

Exercise as a pain management strategy was a new understanding, particularly for those who generally avoided activity, helping to resolve a fear that activity would cause more harm to their affected joint.

Program participation increased pain levels and caused significant discomfort for almost one-quarter of participants (23%) many of whom self-reported that they have more advanced OA. One-third of these participants felt the increased pain was too much to continue and opted to discontinue the program. Some of those who continued through the program, despite the initial pain, reported functional improvements (e.g., lifting, walking, stairs, returning to activities) from exercising and, later, a reduction in pain. For others who progressed through the program, this was not the case and they experienced persistent pain throughout, as stated by Participant 28,

We did test results, see how we stand up on certain things she had us do the first time. And in every one, I was better than I was at first. But I was having more pain. That was sort of the irreconcilable fact that although I was performing better, I was having more pain. (Participant 28)

Improved mobility

Descriptors such as stamina, stability, speed, improved joint alignment and range of motion, particularly with knee extension underlie the perceptions around improvements in mobility. From the participants’ perspective, these physical gains also translated to ease of movement and functional improvements, which impacted their overall sense of well-being. Almost half of the participants (43%) reported that daily life activities were no longer difficult: using the bathroom, going up and down stairs, turning in bed, gardening, housework, regular exercise, and playing with grandchildren on the floor; all became possible with their improved mobility, as reflected in the experiences of Participant 17,

I was able to do the stairs better after, after that program.. And getting off the toilet was another one. (Participant 17)

With improved functioning and mobility of the joint, over half of the participants (53%) became more physically active, beyond the exercises delivered through the program. Participants caught themselves re-starting activities they had stopped because the pain and poor mobility were no longer limiting factors; for example, engaging in more intensive physical activity such as biking, hiking, horseback riding, curling or cross-country skiing. As reflected in the experience of Participant 21:

…about four weeks into the exercises, I found that I could get on the horse. But what really surprised me was, it was not my knee that improved as much as my hips…when I swung onto the horse prior to that I had trouble getting my leg over the cantle. And when I swung on I looked down and I cleared it by at least six inches. (Participant 21)

Improved strength

Almost half of the participants (47%) felt muscle strengthening was an important benefit. Some participants indicated they had prior knowledge about the benefits of strengthening exercises to manage their OA, while most acquired this new knowledge throughout the program. They felt the program offered strengthening exercises that targeted the joint specifically. Some participants also realized that improved strength stabilized and reduced stress on their joints, contributing to pain management, and improved mobility. Participants expressed that these strength gains allowed them to engage in activities that took advantage of, and helped maintain, that improved strength, as stated by Participant 12,

…I think I was much stronger. My legs were stronger. And last summer I did do some hiking, which I had not done the summer before. (Participant 12)

In addition to the above, participants described indirect wellness benefits resulting from their participation in the program such as changes in their overall physique due to weight loss and overall muscle toning from regular engagement in physical exercise. Overall, the benefits and gains from the program met, and at times exceeded, many participants’ expectations (53%); one participant expressed that given the improvements experienced, joint replacement surgery was no longer a consideration for them,

I loved it. I think everybody should do it… I’m a big promoter of the program, absolutely. Because I’m at a level right now where I’m thinking, I don’t need surgery! (Participant 1)

Self-efficacy

Participants indicated that the program’s structure, group format, weekly commitment, and exercise progressions left them feeling empowered to better manage their condition. Three emergent sub-themes characterized the self-efficacy experienced by participants: (1) confidence regarding physical activity and exercise, (2) awareness of movement, and (3) motivation to be and remain active. Selected illustrative quotes of these sub-themes are presented in text with additional quotes provided in Table 3.

Confidence

Participants left the program with a stronger sense of confidence in managing their condition, which was closely linked to learning. Almost half of participants (46%) felt the program served as an opportunity to review and build upon their existing knowledge; however, for the majority of participants (53%), the program offered new knowledge and insights about how to effectively manage their OA. As expressed by Participant 20:

… just a simple thing… I was walking wrong and it was causing more problems with my sore ankles. Which was probably causing problems for my knee and my hip. And it’s a simple thing, how to walk properly. (Participant 20)

Enhanced confidence also addressed underlying uncertainty regarding movement and what to do with sensations experienced by participants during movement that often resulted in hesitation and, at times, ceasing activity altogether. In addition to a better understanding of correct movement, experiencing improvements in strength and mobility directly impacted participant’s certainty and motivation to engage in physical activity. For example,

…it’s more my confidence in my knees that improved… I can go out on an average day between 3,000 and 4,000 [steps]. But I take a walking stick. (Participant 14)

Awareness

For over one-third of participants (37%), an important benefit of the program was the development of awareness– joint alignment, body position, and correct movement techniques. This awareness was applied when exercising and during functional activities such as sitting down, standing up, and walking. As explained by Participant 22,

A little bit… I’m still retraining my brain. How to walk without a limp. And that’s the hardest part… but when I walk without the limp there’s hardly any pain. But when I lose control over the brain… and I start limping—I’ll get really bad pain. (Participant 22)

Beyond an understanding and application of proper alignment in movements, participants described a better awareness of the connection between pain and exercise and how they used this understanding to maintain or increase their physical activity and mobility. For example, some noted that increased mobility reduced pain and that increased pain signalled a need for more mobility (and movement). As stated by Participant 1:

…when I stop doing those exercises, my knee acts up… it’s hurting more. Yeah. And I know it’s ‘cause I’ve got to get back to it. (Participant 1)

Such awareness resulted in an important shift in the understanding of OA– whereas, before the GLA:D program, pain was often a debilitating factor that prevented movement, afterwards the sensation of pain was used by participants as an indicator they needed to resume exercise or practice specific exercises once more.

Motivation

The GLA:D program appeared to be a source of motivation for participants to exercise and to remain physically active. For over half of the participants (53%), the program was the vehicle by which regular exercise became an established or re-established part of their daily routines. For some, it provided the structure that enabled perseverance, particularly through the initial stages of the program which had challenges associated with learning new exercises, overcoming de-conditioning, and a lower fitness level. For example, Participant 29 stated,

…it pushed me to do more than what I would have. I could easily have been lazy and… just have gotten to… a comfortable point. Whereas this one pushed me. And I have to admit, I needed that. It was great.. (Participant 29)

For others, the benefits experienced throughout the program (e.g., the health improvements, newfound confidence in their physical abilities, independence to exercise at home, and direct link between exercise and pain) were motivating factors to continue with the program and maintaining an exercise routine after program completion. As stated by Participant 16,

Well, I can tell you that even during the program itself I noticed… increased strength… in my knees specifically.. it increased my motivation to actually do more to actually strengthen the muscles in the knee, both the side muscles as well as the front and back muscles in my legs and knees. (Participant 16)

Overall, the analysis of participant interview data resulted in several sub-themes on the benefits of the GLA:D program, many of which align with the quantitative measures reported in the GLA:D annual reports [20]. Yet, these quantitative measures are not independent of one another; instead, they are interrelated constructs, and these connections were elucidated through the participants’ perceptions and experiences. Figure 1 below visualizes the connection between the sub-themes.

Participants’ experiences suggest that pain had a bidirectional relationship with movement and exercise, whereby increased mobility through the exercises in the program led to reduced pain. As the participant decreased their movement, an increase in pain signalled the need for more movement and exercise. This realization was a result of increased awareness, gained throughout the program which helped the individual redefine pain as not a debilitating factor but an indicator to promote self-management. The outcomes of physical activity (i.e., increased mobility and strength) were related to awareness, confidence, and motivation. For example, participants gained familiarity and confidence with the exercises as well as an awareness of their body’s alignment while performing those exercises. This allowed individuals to become comfortable exercising again and the benefits gained during the program motivated individuals to sustain physical activity after program completion, thus supporting sustained behaviour change and self-management of their OA.

Lack of benefit

The program was not perceived as beneficial for all participants in managing their OA-associated symptoms (see Table 4 for supportive quotes); 23% of participants felt they did not benefit at all from the program, due to experiencing minimal or inconsistent gains in pain reduction and/or improved mobility. Two participants also noted other health issues that precluded effective participation in the program and hence did not benefit from the program. The majority of those who did not feel they benefitted from the program felt their OA progressed too far for them to be good candidates for the program. For example, one participant stated,

I was too far gone for the GLA:D program. (Participant 11)

These participants reflected on the need for GLA:D to be available earlier in their disease progression to manage expectations in a more effective way for those with very advanced OA, as stated by Participant 28,

… she [the GLA:D provider] said to me on the last day…you might have just had been better off if you’d gotten into the program earlier. You might have had a better chance for success. (Participant 28)

Over one-quarter of the participants (27%) had a mixed response to the program, whereby they described it as providing benefit to some but not all aspects of their OA-associated experiences. For example, some found it reduced their pain levels, but they were unable to achieve their anticipated goals (e.g., walking down the stairs confidently). Others recognized improved strength, but they did not experience consistent pain reduction. Lastly, as noted in the above section on wellness, some experienced persistent pain throughout the program, which they associated with the program exercises.

Discussion

This qualitative interpretive description study examined participants’ perceived benefits experienced through their participation in the GLA:D program in Alberta, Canada. Most participants felt they benefitted from the program, which led to improvements in mobility, activities of daily living, and pain management, as well as increased their motivation, awareness, and confidence in managing pain and becoming more physical active. However, almost one-quarter of participants did not perceive the program to be beneficial. Lack of mobility and/or unrelenting joint pain were reasons why they felt their OA was too advanced to benefit from the program. The qualitatively described benefits, and lack thereof, reported in these interviews provide added depth to the quantitative outcomes reported in the GLA:D Annual Report [20] and helped to elucidate the connections between the different types of benefits.

We found several program benefits reported by participants were not currently being measured in the GLA:D database but were important to participants. First, participants also described their growing confidence to exercise, engage in activities of daily living, and manage their OA symptoms. This confidence represents a sense of self-efficacy and is an important construct in many health behaviour change models [29,30,31]. Self-efficacy is associated with adherence to exercise regimes among individuals living with OA [32, 33], therefore, the growth of self-efficacy as a part of GLA:D can help sustain its benefits after program completion. Second, ancillary benefits such as improvement in strength were frequently mentioned. These benefits were associated with participation in the program exercises and acted as a motivating factor to continue to practice the GLA:D exercises or other physical activity which thus resulted in increased strength. This strengthening was described in reference to the areas targeted by the program (e.g., legs, glutes) as well as other muscle groups indirectly targeted by the program exercises (e.g., abs, arms). This finding enhances our understanding of the benefits of the programs beyond the information on functional movements tests (i.e., 30-second sit stand and 40-metre walk test) and sport and recreation-related physical function that are captured in the GLA:D database. Moreover, this strengthening was closely tied with an important success factor for many participants- their ability to return to previous activities that had become out of reach due to their OA.

Findings from this diverse sample of participants indicated a variety of views on the benefits of the GLA:D program. Many of the participants interviewed reported better pain management. Yet not all participants experienced pain relief; some participants in the present study indicated that participation in the program increased their pain. These contrasting experiences of movement and pain may help to explain the findings of a quantitative study which found that both improved and worsening pain were associated with physical activity among GLA:D program participants [34]. Some participants experienced immediate pain after the first session and were not able to continue. This response to the exercises is expected from some participants and providers are trained to prepare participants for this initial pain reaction and reassure them that the pain will likely subside over time. These perspectives highlight a need to better support participants in this initial stage of the program. Past research examining gender-related differences in pain responses found that program-related factors such as attending former participant lectures and attending more exercise classes impacted women’s likelihood of experiencing pain reductions while men’s mental health and comorbidities impact their likelihood of experiencing pain reductions [35]. Based on these responses and findings from others, the program may need a tailored approach informed by factors such as gender. Future research should focus on examining what factors impact the likelihood of obtaining clinically relevant pain relief.

The other participants who continued in the program, but experienced worsened pain described themselves as poorly suited to the program. These insights highlight the need to provide people living with knee or hip OA with an intervention through referrals to the GLA:D program in the earlier stages of OA. Given that these study results represent findings from some of the first individuals to participate in the GLA:D program in Alberta, it is possible that individuals with knee and hip OA were referred regardless of OA severity. This is supported by findings from our previous evaluation of GLA:D providers who stated that they often struggled with recruitment [22]. These novel findings on GLA:D participants’ experiences with pain may elucidate some reasons as to why a subset of participants are not experiencing pain-related benefits but experiencing increasing pain, a trend observed in Canada, Australia, and Denmark [11]. As the number of sites offering the GLA:D program grows and awareness of the program increases, these findings provide important insights that can assist in continued quality improvement of global implementation of GLA:D.

This study has several strengths. First, to our knowledge, this is the first study to report participants’ perceptions of the benefits of the GLA:D program, providing deeper insights into the program benefits, some confirmatory and some novel, experienced by participants. In addition, these findings enhance our understanding as to why not all participants are experiencing benefits from the program. Second, we purposively sought a diverse representation of participants, including those in rural and urban areas as well as across payment models (e.g., paying privately or public coverage). This enables our results to better reflect the provincial context and be transferable to other regions with a similar implementation context (i.e., single-payer healthcare systems with limited coverage for the program). Future research may wish to explore patient experiences of the GLA:D program based on participants’ characteristics (e.g., race/ethnicity, diverse gender identity, income, age) or provider characteristics (e.g., type of provider) rather contextual factors that might require a larger sample size to achieve saturation. Despite these strengths, this study also has limitations that require consideration. First, the interviews occurred up to 12 months after the participants completed the program, which increases the potential for recall bias. While outside of the scope of the current project, future research might wish to examine whether the benefits reported in the present manuscript were sustained beyond 12 months. Second, member checking was not completed; therefore, the transcripts were not shared with patients for input and feedback, which increased the chance of researcher bias. Lastly, our research team did not include people living with OA; however, the overall evaluation of the GLA:D program was informed by patient advisors engaged in provincial OA initiatives.

Conclusions

Individuals with hip and knee OA who participated in the GLA:D program perceived many benefits from participation including improvements in pain, joint function, strength, and mobility and they regained the ability to complete activities of daily living and participate in leisure and sports that they had previously given up. Participants also felt the program instilled a new sense of confidence and awareness allowing them to better manage their OA symptoms and ultimately resulting in motivation to embed the program learnings in their everyday lives to maintain the benefits. Participant experiences indicated that the program had an impact on their overall sense of well-being through regaining ease of movement, the relief that something helped their OA, the enjoyment of returning to activities, and not being restricted or limited in terms of their activities. For participants who did not experience benefits, this was largely due to pain, the severity of their OA, and the program’s failure to meet their anticipated goals. Earlier intervention with the GLA:D program and improved screening may assist in improving the number of participants who benefit from the program.

Data availability

The full data set is not publicly available for reasons of confidentiality. De-identified interview transcripts may be requested from the corresponding authors. Release of de-identified interview data will be dependent up on ethics review and approval.

Abbreviations

- GLA:D:

-

Good Life with osteoArthritis: Denmark

- OA:

-

Osteoarthritis

- COREQ:

-

Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research

References

Sarzi-Puttini P, Cimmino MA, Scarpa R, Caporali R, Parazzini F, Zaninelli A, Atzeni F, Canesi B (2005) Osteoarthritis: an overview of the disease and its treatment strategies. Semin Arthritis Rheum 35:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2005.01.013

Burrows NJ, Barry BK, Sturnieks DL, Booth J, Jones MD (2020) The relationship between daily physical activity and pain in individuals with knee osteoarthritis. Pain Med 21:2481–2495. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnaa096

Kontio T, Viikari-Juntura E, Solovieva S (2020) Effect of osteoarthritis on work participation and loss of working life–years. J Rheumatol 47:597–604. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.181284

Park H-M, Kim H-S, Lee Y-J (2020) Knee osteoarthritis and its association with mental health and health-related quality of life: a nationwide cross-sectional study. Geriatr Gerontol Int 20:379–383. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.13879

Cook C, Pietrobon R, Hegedus E (2007) Osteoarthritis and the impact on quality of life health indicators. Rheumatol Int 27:315–321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-006-0269-2

Bannuru RR, Osani MC, Vaysbrot EE, Arden NK, Bennell K, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, Kraus VB, Lohmander LS, Abbott JH, Bhandari M, Blanco FJ, Espinosa R, Haugen IK, Lin J, Mandl LA, Moilanen E, Nakamura N, Snyder-Mackler L, Trojian T, Underwood M, McAlindon TE (2019) OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 27:1578–1589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2019.06.011

Østerås N, Jordan KP, Clausen B, Cordeiro C, Dziedzic K, Edwards J, Grønhaug G, Higginbottom A, Lund H, Pacheco G, Pais S, Hagen KB (2015) Self-reported quality care for knee osteoarthritis: comparisons across Denmark, Norway, Portugal and the UK. RMD Open 1:e000136. https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2015-000136

King LK, Marshall DA, Faris P, Woodhouse LJ, Jones CA, Noseworthy T, Bohm E, Dunbar MJ, Hawker GA (2020) Use of recommended non-surgical knee osteoarthritis management in patients prior to total knee arthroplasty: a cross-sectional study. J Rheumatol 47:1253–1260. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.190467

Hart DA, Werle J, Robert J, Kania-Richmond A (2021) Long wait times for knee and hip total joint replacement in Canada: an isolated health system problem, or a symptom of a larger problem? Osteoarthr Cartil Open 3:100141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocarto.2021.100141

Skou ST, Roos EM (2017) Good life with osteoArthritis in Denmark (GLA:DTM): evidence-based education and supervised neuromuscular exercise delivered by certified physiotherapists nationwide. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 18:72. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-017-1439-y

Roos EM, Grønne DT, Skou ST, Zywiel MG, McGlasson R, Barton CJ, Kemp JL, Crossley KM, Davis AM (2021) Immediate outcomes following the GLA:D® program in Denmark, Canada and Australia. A longitudinal analysis including 28,370 patients with symptomatic knee or hip osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 29:502–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2020.12.024

Barton CJ, Kemp JL, Roos EM, Skou ST, Dundules K, Pazzinatto MF, Francis M, Lannin NA, Wallis JA, Crossley KM (2021) Program evaluation of GLA:D® Australia: physiotherapist training outcomes and effectiveness of implementation for people with knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil Open 3:100175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocarto.2021.100175

Davis AM, Kennedy D, Wong R, Robarts S, Skou ST, McGlasson R, Li LC, Roos E (2018) Cross-cultural adaptation and implementation of good life with osteoarthritis in Denmark (GLA:DTM): group education and exercise for hip and knee osteoarthritis is feasible in Canada. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 26:211–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2017.11.005

Thorlund JB, Roos EM, Goro P, Ljungcrantz EG, Grønne DT, Skou ST (2021) Patients use fewer analgesics following supervised exercise therapy and patient education: an observational study of 16 499 patients with knee or hip osteoarthritis. Br J Sports Med 55:670–675. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2019-101265

GLAD International. (nd) International programs. Accessed 11 Apr 2023. https://gladinternational.org/home/international-programs/

GLAD Canada (nd) Locations. Accessed 1 Aug 2023. https://gladcanada.ca/find-nearest-glad/

Wallis JA, Ackerman IN, Brusco NK, Kemp JL, Sherwood J, Young K, Jennings S, Trivett A, Barton CJ (2020) Barriers and enablers to uptake of a contemporary guideline-based management program for hip and knee osteoarthritis: a qualitative study. Osteoarthr Cartil Open 2:100095. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocarto.2020.100095

Ezzat AM, Bell E, Kemp JL, O’Halloran P, Russell T, Wallis J, Barton CJ (2022) “Much better than I thought it was going to be”: telehealth delivered group-based education and exercise was perceived as acceptable among people with knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil Open 4:100271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocarto.2022.100271

Kania-Richmond A, Beaupre LA, Jessiman-Perreault G, Tribo D, Martyn J, Hart DA, Robert J, Slomp M, Jones CA (2024) ‘I do hope more people can benefit from it.’: the qualitative experience of individuals living with osteoarthritis who participated in the GLA:DTM program in Alberta, Canada. PLoS ONE 19:e0298618. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0298618

McGlasson R, Zywiel MG (2021) GLA:DTM Canada annual report 2020. Bone and Joint Canada

Glasgow RE, Harden SM, Gaglio B, Rabin B, Smith ML, Porter GC, Ory MG, Estabrooks PA (2019) RE-AIM planning and evaluation framework: adapting to new science and practice with a 20-year review. Front Public Health 7

Kania-Richmond A, Jones CA, Martyn J, Hastings S, Ellis K, Jessiman-Perreault G, Hart DA, Robert J, Slomp M, Beaupre LA (2023) Implementing a guideline-based education and exercise program for people with knee and hip osteoarthritis-practical experiences of providers and clinic leaders: a qualitative study. Musculoskeletal Care. https://doi.org/10.1002/msc.1801

Thorne S (2016) Interpretive description: qualitative research for applied practice, 2nd edn. Routledge, New York

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J (2007) Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 19:349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

Government of Alberta (2023) Population statistics. Accessed 11 Apr 2023. https://www.alberta.ca/population-statistics.aspx

Government of Alberta (2023) Health care services covered in Alberta. Accessed 11 Apr 2023. https://www.alberta.ca/ahcip-what-is-covered.aspx

Alberta Health Services and Alberta Health (2018) Official Standards Geographic Areas. Accessed 11 Apr 2023. https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/a14b50c9-94b2-4024-8ee5-c13fb70abb4a/resource/70fd0f2c-5a7c-45a3-bdaa-e1b4f4c5d9a4/download/official-standard-geographic-area-document.pdf

Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, Baker S, Waterfield J, Bartlam B, Burroughs H, Jinks C (2018) Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant 52:1893–1907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8

Maiman LA, Becker MH (1974) The health belief model: origins and correlates in psychological theory. Health Educ Monogr 2:336–353. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019817400200404

Bandura A (1997) Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. Freeman, New York, NY, US

Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 50:179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Degerstedt Å, Alinaghizadeh H, Thorstensson CA, Olsson CB (2020) High self-efficacy– a predictor of reduced pain and higher levels of physical activity among patients with osteoarthritis: an observational study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 21:380. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-020-03407-x

Hammer NM, Bieler T, Beyer N, Midtgaard J (2016) The impact of self-efficacy on physical activity maintenance in patients with hip osteoarthritis– a mixed methods study. Disabil Rehabil 38:1691–1704. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2015.1107642

Baumbach L, Grønne DT, Møller NC, Skou ST, Roos EM (2023) Changes in physical activity and the association between pain and physical activity - a longitudinal analysis of 17,454 patients with knee or hip osteoarthritis from the GLA:D® registry. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 31:258–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2022.09.012

Perruccio AV, Roos EM, Skou ST, Grønne DT, Davis AM (2023) Factors influencing pain response following patient education and supervised exercise in male and female subjects with hip osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res 75:1140–1146. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.24954

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Kira Ellis (KE), Staci Hastings (SH), and Emily McKenzie (EM) for their contribution to this work. The authors would also like to acknowledge and thank the participants who contribute their valuable insights to the evaluation.

Funding

We have no funding to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The GLA:D Alberta evaluation was co-led by A.K.R., L.A.B., and C.A.J., with conceptual input from J.R., M.S., and D.A.H. Data collection was conducted by A.K.R. Data analysis involved A.K.R., D.T., L.A.B., C.A.J., and G.J.P. The manuscript was prepared by A.K.R., G.J.P., and D.T. The manuscript was reviewed and edited by L.A.B., D.T., J.M., D.A.H., J.R., M.S., and C.A.J. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval for this study was received from the Health Research Ethics Review Board of the University of Alberta (Pro00068308) on January 17, 2017. All participants provided verbal consent to voluntary participation in the study, prior to the initiation of the interview.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kania-Richmond, A., Beaupre, L., Jessiman-Perreault, G. et al. Participants’ perceived benefits from the GLA:D™ program for individuals living with hip and knee osteoarthritis: a qualitative study. J Patient Rep Outcomes 8, 62 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41687-024-00740-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41687-024-00740-w