Abstract

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) represent the world’s leading cause of death. Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is a widely applied concept of patients’ perceived health and is directly linked to CVD morbidity, mortality, and re-hospitalization rates. Cardiac rehabilitation (CR) improves both cardiovascular outcomes and HRQoL. Regrettably, CR is still underutilized, especially in subgroups like women and elderly patients. The aim of our study was to investigate the predictive potential of sex and age on change of HRQoL throughout outpatient CR.

Methods

497 patients of outpatient CR were retrospectively assessed from August 2015 to September 2019 at the University Hospital Zurich. A final sample of 153 individuals with full HRQoL data both at CR entry and discharge was analyzed. HRQoL was measured using the 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36) with its physical (PCS) and mental (MCS) component scale. In two-factorial analyses of variance, we analyzed sex- and age-specific changes in HRQoL scores throughout CR, adjusting for psychosocial and clinical characteristics. Age was grouped into participants over and under the age of 65.

Results

In both sexes, mean scores of physical HRQoL improved significantly during CR (p <.001), while mean scores of mental HRQoL improved significantly in men only (p =.003). Women under the age of 65 had significantly greater physical HRQoL improvements throughout CR, compared with men under 65 (p =.043) and women over 65 years of age (p =.014). Sex and age did not predict changes in mental HRQoL throughout CR.

Conclusions

Younger women in particular benefit from CR with regard to their physical HRQoL. Among older participants, women report equal improvements of physical HRQoL than men. Our results indicate that sex- and age-related aspects of HRQoL outcomes should be considered in CR.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), cardiovascular diseases (CVD) continue to represent the world’s leading cause of death [1] in both men and women. Estimates suggest 17.9 million lives lost per year (representing 32% of global mortality), with one third of these deaths prematurely occurring in people under 70 years of age. CVD are, thus, not only a major public health burden, but also strongly affect a patients’ quality of life. Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) a widely applied, multidimensional concept has hereby proven to be a reliable measure of patients’ perceived health [2, 3]. Over the last few years, evidence on an association between poor HRQoL and worse CVD outcome has emerged [4], with poor HRQoL now being recognized as an independent predictor for higher morbidity, mortality, and re-hospitalization rates [5]. In recent years, HRQoL has thus become widely established as an important outcome measure in cardiac care and secondary prevention [6].

In women, CVD is under-recognized due to often atypical clinical presentations, leading to disadvantages in primary and secondary prevention and CVD outcomes [7]. Unfortunately, women with CVD are not only more susceptible to psychosocial stress [8, 9] and worse mental [10] and social [11] health than men, but also show lower HRQoL both at admission to cardiac rehabilitation (CR) and at follow-up [10, 12, 13].

Hence, due attention should be directed to secondary prevention of CVD to positively influence cardiovascular outcome. Considerations of traditional risk factors create the basis for prevention of CVD, yet the impact of sex- [14] and age- [13] specific aspects on CVD outcome is increasingly recognized. Unfortunately, gender gaps still exist disadvantaging women in cardiac care and secondary prevention leading to unfavorable cardiovascular outcomes in women [15]. Women are underrepresented in cardiac research and results are often generalized and not reported in a gender-specific way. As a result, international guidelines and clinical practice are still biased towards men due to a lack of knowledge about sex-specific aspects [16].

As a key element of secondary prevention [17, 18], CR is strongly recommended by international guidelines. CR not only positively influences cardiovascular outcomes [19, 20], but also improves psychosocial distress and HRQoL [21,22,23], the effect still being present in a longer-term follow-up [24]. Notwithstanding the fact that CR is still underutilized [25, 26], especially in women [27,28,29], who show greater improvement in mortality rate after CR and greater treatment adherence compared to men [30,31,32]. Barriers to CR referral have also been reported for elderly patients [33], particularly women [34]. In view of the beneficial effects of CR also in the elderly [13, 35], this is critical and the early targeting of sex- and age-specific [10, 32] needs is crucial. The assessment of potentially relevant psychosocial factors, complementary to modifying traditional risk factors, may allow optimized referral [36] to CR for vulnerable subgroups improving secondary prevention effects and the overall outcome of CVD.

To date, there is only minimal evidence concerning sex- and age- dependent differences in HRQoL in CR patients [10, 12, 13], and the overall outcome is inconclusive. The aim of our monocentric, observational, retrospective study was, thus, to further elucidate the predictive potential of sex and age on change of HRQoL scores in outpatient CR, adjusting for potentially relevant psychosocial and clinical aspects.

Methods

Study design and participants

In this monocentric, observational, retrospective study, we assessed data of 497 potentially eligible participants of outpatient CR at the University Hospital Zurich from August 2015 to September 2019. The standardized outpatient CR program comprises 12 weeks of strength and endurance training in 34 sessions of 90 min each. HRQoL assessments were conducted at CR entry and discharge. We included all CR participants, who completed the CR program, had full HRQoL data at both measurement points and who gave written informed consent for the use of their health-related data for research with admission to CR. The study was approved by the Ethics committee of Canton Zurich, Switzerland (REQ-2020-0047).

Measures

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL)

HRQoL was assessed at CR entry and discharge using the 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36) with norm-based scores. The SF-36 is a highly reliable [37], established and broadly employed HRQoL questionnaire measuring patients’ perceived emotional and physical health [38]. The SF-36 comprises 36 questions evaluating eight different state-of-health dimensions (vitality, physical functioning, bodily pain, general health perceptions, role limitations in the sense of interference with normal activities due to physical health problems, role limitations due to personal or emotional problems, emotional well-being and social functioning). Those dimensions are summarized into two health component scales: the physical (PCS) and mental component summary scale (MCS) [39]. Scores in each domain range from a minimum of 0 (poor HRQoL) to a maximum of 100 (high HRQoL).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using R version 4.2.0 [40]. The primary outcome of interest was the change in physical and mental HRQoL scores (PCS, MCS) from CR entry to discharge.

First, we performed a preliminary one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to detect disease-related, independent variables other than sex with significant impact on physical and mental HRQoL. We used one-way ANOVA and paired-sample t-tests to assess sex-related baseline characteristics as well as to calculate the between-group differences on HRQoL subdomains. We assessed the predictive potential of sex and age (grouped +/- 65 years of age) on SF-36 HRQoL change scores between entry and discharge from CR by means of analysis of variance, using sex as grouping variable. Since sex-specific effects for different age groups were reported [41], we included an interaction term sex x age-group in our analyses. Cases with incomplete data were excluded from our analysis.

Based on previous research and clinical experience, we controlled for the following psychosocial and disease-related covariates: housing situation (living alone vs. living with others), presence of a psychiatric disorder, change in 6-minute-walk distance (calculated using the difference between the walk distance at CR entry and discharge), ischemic heart disease and modifiable traditional cardiovascular risk factors (hypertension, dyslipidemia, overweight, smoking and type II diabetes). Social support (assessed with housing situation as a proxy) is reportedly associated with higher psychological well-being and prevention of emotional distress after cardiac disease [42, 43], while the presence of a psychiatric disorder impacts negatively on CR outcomes [44]. With regard to the 6MWD, better 6MWD performance has been linked to greater HRQoL improvements [13, 41].

Results

Baseline clinical characteristics

A total of n = 153 individuals with complete data including HRQoL data at both CR entry and discharge were analyzed (Fig. 1). Of the excluded patients n = 57 had missing data at CR entry, n = 151 had missing data at CR discharge and n = 114 had missing HRQoL data at both measurement points. Baseline characteristics of the 153 study participants are displayed in Table 1. More than four fifth where male, with an average age of 59.53 (SD = 12.21) years. Female patients were older at CR admission than their male counterparts. In both sexes, over two thirds lived in a household of two or more persons. Comorbid psychiatric disorders were rare (< 15% of the sample).

The 153 included patients did not differ significantly from the 344 excluded participants in terms of age and sex. (Table 1, Appendix).

HRQoL mean scores with entry to and discharge from CR

In paired-sample t-tests both sexes improved significantly in their physical HRQoL throughout CR (p <.001). However, with regard to mental HRQoL, significant improvements were observed in men only (p =.003). Women had significantly lower physical HRQoL than men at entry to CR, but not with discharge from CR. Mental HRQoL did not differ between sexes, neither at entry to, nor at discharge from CR. The mean scores of physical and mental HRQoL at CR entry and discharge CR are displayed in Table 2.

Predictors of HRQoL

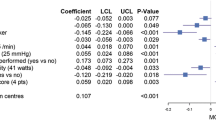

In two-factorial analyses of variance, associations between gender, age, psychosocial and disease-related variables and the change in HRQoL were calculated. The overall model explained 50.4% of the variance (η² = 0.504) for physical HRQoL and 41.1% of the variance (η² = 0.411) for mental HRQoL (Table 3).

Sex and age as predictors of HRQoL

In analyses of variance (Table 3) on changes in physical HRQoL, main effects of sex and age (grouped +/- 65 years) were not significant. However, the interaction sex*age-group proved to be statistically significant (F(1,128) = 4.22, p =.042). We performed a post-hoc analysis (Bonferroni-Holm) controlling for multiple testing to differentially assess the predictive potential of the 4 groups (women over/under 65 and men over/under 65 years of age). Being female and below 65 years of age predicted the greatest improvements of physical HRQoL throughout CR, compared to women over 65 (p =.014), and men under 65 (p =.043). Figure 2 displays the changes of physical HRQoL scores by subgroups, as revealed in post-hoc analysis.

With regard to mental HRQoL, sex, age (grouped +/- 65 years) and the interaction sex* age-group showed no significant association with mental HRQoL changes throughout CR.

Discussion

This monocentric observational, retrospective study on 153 participants in outpatient CR examined the predictive potential of sex and age on changes of HRQoL throughout CR.

CR improved mean scores of physical HRQoL in both sexes, those of mental HRQoL only in men.

With regard to physical HRQoL, we found younger women under 65 years of age to particularly benefit from CR with regard to their physical HRQoL, Older women, however, showed the same improvements in physical HRQoL as older men. With regard to mental HRQoL, older age predicted greater improvements throughout CR, while sex and its interaction with age revealed no predictive potential on mental HRQoL change.

Current evidence on sex- and age-related differences of HRQoL in cardiac patients is scarce. A few small scale studies show poorer HRQoL in women with CVD after short-term follow-up [45,46,47,48]. In CR, women report poorer mental health (anxiety and depression) at CR entry compared to men [49]. Specific sex- and age-related effects of CR on HRQoL outcomes are poorly explored. Our results confirm previous findings of poorer physical and mental HRQoL [10, 12] in women compared to men at entry to outpatient CR and poorer emotional and physical HRQoL in women compared to men at entry to inpatient CR [13]. The greater improvement of physical HRQoL we observed in younger women compared with younger men is in agreement with comparable recent findings [13], and in disagreement with others [10]. These divergent results might be partially explained by the differing sample sizes [13] and patient characteristics, e.g. higher proportion of women in the total sample [10, 12, 13]. This significantly higher improvement in physical HRQoL of younger women compared with men throughout CR is, however, to be particularly emphasized. Physical activity positively impacts HRQoL [50], with women benefiting particularly from tailored CR programs [51]. Concurrently, women and younger participants especially benefit from CR by improving their exercise capacity [52]. Physical inactivity at the same time represents a recognized cardiovascular risk factor [53]; furthermore, the positive effects of physical activity on CVD [54] have already been documented and should be properly addressed, improving secondary as well as primary cardiac prevention. On the one hand, the lack of activity and its negative impacts on HRQoL especially in women should be highlighted, particularly considering the benefit CR has on improving their physical HRQoL. On the other hand, the importance of CR referral should particularly be emphasized for women given the described sex-disparity, thus encouraging physical activity in women.

With regard to mental HRQoL, our results show no significant associations between age and sex on mental HRQoL changes throughout CR. This is in contrast to previous evidence of greater mental HRQoL improvements in elderly patients (> 75 years) [13]. The fact that we did not see these effects could have been due to our smaller sample size. Also, the different grouping of age in the aforementioned and our study may have contributed to these discrepant findings.

In our study, we controlled for the social factor of living alone versus not living alone as a proxy of social support, as well as for the presence of a comorbid psychiatric disorder. Social support has been reported as a relevant and protecting factor for both incidence and prognosis of CVD [55]. Our results did not reveal any difference in HRQoL change scores between participants living alone vs. those not living alone. This may be attributable to our moderate sample size, the predominance of participants in our sample not living alone, as well as not being able to take into account the social support experienced outside one’s household. A three-dimensional questionnaire with physical, mental as well as social aspects of quality of life may be more appropriate to tackle this question [13]. It is also worth noting that our traditional sex-driven constructs may influence the extent and perception of support, affecting women who experience less support on the one hand [56] and struggle to seek it on the other. This may be attributable to the fact that they do not want to burden others or are afraid of not being taken seriously [57]. Interestingly, in a recent systematic review additional psychosocial strategies seem to positively impact on women’s CR outcomes compared to traditional CR [51]. Other strategies in addressing sex-specific needs include women-only CR programs, however, results are inconsistent. While our results suggest that women benefit from traditional CR, there are grounds for considering that tailored CR programs could further improve CR outcomes in women. This again points to the fact that sex-specific and psychosocial aspects relevant to women are still not sufficiently addressed in secondary prevention and CR.

Future larger studies are needed to further focus on these complex interplays between sex, age, psychosocial aspects and CR outcomes to expand knowledge and improve secondary prevention also in vulnerable patient groups.

With regard to psychiatric disorders, CR has been reported to improve mental health outcomes like anxiety and depression [58]. Also, recent evidence found the probability of potentially eligible patients participating in CR to be greater in patients with a psychiatric disorder [59]. Our results hint at psychiatric disorders being associated with lower gain in physical and mental HRQoL during CR.

Strengths and limitations

Given the uniformity of the CR program, we benefited from a well-defined and standardized intervention paradigm. We used the widely applied SF-36 survey for HRQoL assessment, which has been used in countless other studies and offers a sound comparability. The retrospective nature of our study without a control group cannot rule out bias due to spontaneous improvements in HRQoL without participation in a CR program, impairing the representativeness of the results.

The moderate sample size, the underrepresentation of women in our sample and a fair proportion of missing HRQoL data limits the power of our study and the generalizability of results. Missing data on CR discharge should be regarded particularly critically in clinical practice, as they reduce the informative value of the effectiveness of CR in this respect. At the same time, the self-evaluation of HRQoL can also be a helpful assessment tool for the patients themselves in order to objectify the progress made during CR. This important tool should therefore not be dispensed with. The small effect size of our model on mental HRQoL change also needs to be recognized, which limits its informative value. Especially with regard to the changes in mental HRQoL, our sample may have been too small to capture predictive effects of sex and age. Since the CR program is primarily aimed at improving physical functioning, the more subtle effects on mental health could only be visible in a larger sample. Future research on this topic in studies with larger samples is recommended. However, the fact that, we were able to reproduce in substantial respects and in an outpatient setting the findings of an earlier, much larger study on sex-related changes in HRQoL with respect to higher gain in physical HRQoL in younger women clearly shows the relevance of this aspect in CR.

Conclusions

Our findings add to the still meager evidence for sex and age as predictors of HRQoL outcomes in CR. We provide important insights calling for special attention to younger women, who, although having significantly lower physical HRQoL mean scores than men at CR entry, benefit the most from CR in this regard. Among older patients above 65 years of age, women show similar improvements in their physical HRQoL. This observation underscores that the low CR referral and participation rates in women are particularly problematic and need to be focused on in future efforts for optimal cardiovascular prevention. In summary, a better understanding of sex- and age related aspects of HRQoL improvements throughout CR is crucial to allow offsetting substantial disadvantages in vulnerable patient groups and the development of better tailored CR programs in the future.

Data availability

The employed data cannot be publicly disclosed due to privacy and ethical restrictions. The data can be provided upon reasonable request from corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis Of Variance

- CR:

-

Cardiac Rehabilitation

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular Diseases

- HRQoL:

-

Health Related Quality of Life

- MCS:

-

Mental Component Scale

- PCS:

-

Physical Component Scale

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

- SF-36:

-

36-Item Short Form Survey

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- 6MWD:

-

6-Minute-Walk Distance

References

Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs). WHO, 11. Juni 2021, www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds). [Online]

Wood-Dauphinee S (1999) Assessing quality of life in clinical research: from where have we come and where are we going? J Clin Epidemiol vol 52(4):355–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00179-6

Thompson DR, Yu CM (2003) Quality of life in patients with coronary heart disease-I: assessment tools. Health Qual Life Outcomes 1:42. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-1-42. Published 2003 Sep 10

Djärv T, Wikman A, Lagergren P (2012) Number and burden of cardiovascular diseases in relation to health-related quality of life in a cross-sectional population-based cohort study. BMJ Open 2(5):e001554. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001. Published 2012 Oct 25. [Online]

Phyo AZZ, Ryan J, Gonzalez-Chica DA et al (2021) Health-related quality of life and incident cardiovascular disease events in community-dwelling older people: a prospective cohort study. Int J Cardiol 339:170–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2021.07.004. [Online]

de Bakker M, den Uijl I, Ter Hoeve N, van Domburg RT, van den Geleijnse ML et al Association between Exercise Capacity and Health-Related Quality of Life during and after Cardiac Rehabilitation in Acute Coronary Syndrome patients: a subst

Woodward M (2019) Cardiovascular Disease and the female disadvantage. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16(7):1165. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16071165. Published 2019 Apr 1. [Online]

Medina-Inojosa JR, Vinnakota S, Garcia M et al (2019) Role of stress and psychosocial determinants on women’s Cardiovascular Risk and Disease Development. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 28(4):483–489. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2018.7035

Prata J, Ramos S, Martins AQ, Rocha-Gonçalves F, Coelho R (2014) Women with coronary artery disease: do psychosocial factors contribute to a higher cardiovascular risk? Cardiol Rev 22(1):25–29. https://doi.org/10.1097/CRD.0b013e31829e852b

Terada T, Chirico D, Tulloch HE, Scott K, Pipe AL, Reed JL (2019) Sex differences in psychosocial and cardiometabolic health among patients completing cardiac rehabilitation. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 44(11):1237–1245. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2018-0876

Kristofferzon ML, Löfmark R, Carlsson M (2003) Myocardial infarction: gender differences in coping and social support. J Adv Nurs 44(4):360–374. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0309-2402.2003.02815.x

Terada T, Vidal-Almela S, Tulloch HE, Pipe AL, Reed JL (2021) Cardiac Rehabilitation following percutaneous coronary intervention is Associated with Superior Psychological Health and Quality of Life in males but not in females. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 41(5):345–350. https://doi.org/10.1097/HCR.0000000000000597

Jellestad L, Auschra B, Zuccarella-Hackl C et al (2022) Sex and age as predictors of HRQOL change in phase-II cardiac rehabilitation. Eur J Prev Cardiol zwac199. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjpc/zwac199

Agarwala A, Michos ED, Samad Z, Ballantyne CM, Virani SS (2020) The use of sex-specific factors in the Assessment of women’s Cardiovascular Risk. Circulation 141(7):592–599. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.043429

Garcia M, Mulvagh SL, Merz CN, Buring JE, Manson JE (2016) Cardiovascular Disease in women: clinical perspectives. Circ Res and 118(8):1273–1293

Pilote L, Humphries KH (2014) Incorporating sex and gender in cardiovascular research: the time has come. Can J Cardiol 30(7):699–702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2013.09.021

Taylor RS, Walker S, Smart NA et al (2019) Impact of Exercise Rehabilitation on Exercise Capacity and Quality-of-life in Heart failure: individual participant Meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 73(12):1430–1443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.12.072. [Online]

Lee BJ, Go JY, Kim AR et al (2017) Quality of life and physical ability changes after hospital-based Cardiac Rehabilitation in patients with myocardial infarction. Ann Rehabil Med 41(1):121–128. https://doi.org/10.5535/arm.2017.41.1.121

McMahon SR, Ades PA, Thompson PD (2017) The role of cardiac rehabilitation in patients with heart disease. Trends Cardiovasc Med 27(6):420–425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcm.2017.02.005

Long L, Mordi IR, Bridges C et al (2019) Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for adults with heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1(1):CD003331. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003331.pub5. Published 2019 Jan 29

Hurdus B, Munyombwe T, Dondo TB et al (2020) Association of cardiac rehabilitation and health-related quality of life following acute myocardial infarction. Heart 106(22):1726–1731. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2020-316920

Antonakoudis H, Kifnidis K, Andreadis A et al (2006) Cardiac rehabilitation effects on quality of life in patients after acute myocardial infarction. Hippokratia 10(4):176–181

Candelaria D, Randall S, Ladak L, Gallagher R (2020) Health-related quality of life and exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation in contemporary acute coronary syndrome patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Qual Life Res 1007(3):10

Dibben G, Faulkner J, Oldridge N, Rees K, Thompson DR, Zwisler AD et al (2021) Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev and 11(11):Cd001800

Freeman AM, Taub PR, Lo HC, Ornish D (2019) Intensive Cardiac Rehabilitation: an underutilized resource. Curr Cardiol Rep 21(4):19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-019-1104-1. Published 2019 Mar 4

Galati A, Piccoli M, Tourkmani N et al (2018) Cardiac rehabilitation in women: state of the art and strategies to overcome the current barriers. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 19(12):689–697. https://doi.org/10.2459/JCM.0000000000000730

Khadanga S, Gaalema DE, Savage P, Ades PA (2021) Underutilization of Cardiac Rehabilitation in women: BARRIERS AND SOLUTIONS. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 41(4):207–213. https://doi.org/10.1097/HCR.0000000000000629

Supervía M, Medina-Inojosa JR, Yeung C et al (2017) Cardiac Rehabilitation for women: a systematic review of barriers and solutions. Mayo Clin Proc S0025–6196(17)30026–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.01.002. published online ahead of print, 2017 Mar 13

MacDonald SL, Hall RE, Bell CM, Cronin S, Jaglal SB (2022) Sex differences in the outcomes of adults admitted to inpatient rehabilitation after stroke. PM R 14(7):779–785. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmrj.12660

Alemán JF, Rueda B (2019) Influencia Del género sobre factores de protección y vulnerabilidad, la adherencia y calidad de vida en pacientes con enfermedad cardiovascular [Influence of gender on protective and vulnerability factors, adherence and quality of life. In patients with cardiovascular disease]. Aten Primaria 51(9):529–535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aprim.2018.07.003

Colbert JD, Martin BJ, Haykowsky MJ et al (2015) Cardiac rehabilitation referral, attendance and mortality in women. Eur J Prev Cardiol 22(8):979–986. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487314545279

Smith JR, Thomas RJ, Bonikowske AR, Hammer SM, Olson TP (2022) Sex Differences in Cardiac Rehabilitation Outcomes [published correction appears in Circ Res. Mar 18 and 2022, 130(6):e22]. Circ Res 130(4):552–565. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.319894

Ruano-Ravina A, Pena-Gil C, Abu-Assi E et al (2016) Participation and adherence to cardiac rehabilitation programs. A systematic review. Int J Cardiol 223:436–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.08.120

Worcester MU, Murphy BM, Mee VK, Roberts SB, Goble AJ Cardiac rehabilitation programmes: predictors of non-attendance and drop-out. European journal of cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation: official journal of the European Society of Cardiology

Bierbauer W, Scholz U, Bermudez T, Debeer D, Coch M, Fleisch-Silvestri R et al (2020) Improvements in exercise capacity of older adults during cardiac rehabilitation. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2047487320914736

Benzer W (2019) How to identify and fill in the gaps in cardiac rehabilitation referral? Eur J Prev Cardiol 26(2):135–137. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487318811695

Brazier JE, Harper R, Jones NM et al (1992) Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: new outcome measure for primary care. BMJ 305(6846):160–164. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.305.6846.160

Lins L, Carvalho FM (2016) SF-36 total score as a single measure of health-related quality of life: scoping review. SAGE Open Med 4:2050312116671725. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312116671725. Published 2016 Oct 4

Ware J, MA K, Keller SD (1993) SF-36 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales: a User’s Manual 8:23–8

R Core Team (2022) R: a Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna

Serra AJ, de Carvalho Pde T, Lanza F et al (2015) Correlation of six-minute walking performance with quality of life is domain- and gender-specific in healthy older adults. PLoS ONE 10(2):e0117359. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0117359. Published 2015 Feb 19

Hsu HC (2020) Typologies of loneliness, isolation and Living Alone Are Associated with Psychological Well-Being among older adults in Taipei: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(24):9181. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph172. Published 2020 Dec 8

Blikman MJ, Jacobsen HR, Eide GE, Meland E (2014) How Important Are Social Support, Expectations and Coping Patterns during Cardiac Rehabilitation. Rehabil Res Pract 2014:973549. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/973549

Bermudez T, Bierbauer W, Scholz U, Hermann M (2022) Depression and anxiety in cardiac rehabilitation: differential associations with changes in exercise capacity and quality of life. Anxiety Stress Coping 35(2):204–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2021.1952191

Ghasemi E et al (2014) Quality of life in women with coronary artery disease. Iran Red Crescent Med J 16(7):e10188. https://doi.org/10.5812/ircmj.10188

Norris CM, Spertus JA, Jensen L et al (2008) Sex and gender discrepancies in health-related quality of life outcomes among patients with established coronary artery disease. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 1(2):123–130. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.793448

Munyombwe T, Hall M, Dondo TB et al (2020) Quality of life trajectories in survivors of acute myocardial infarction: a national longitudinal study. Heart 106(1):33–39. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2019-315510

Oreel TH, Nieuwkerk PT, Hartog ID et al (2020) Gender differences in quality of life in coronary artery disease patients with comorbidities undergoing coronary revascularization. PLoS ONE 15(6):e0234543. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.02. Published 2020 Jun 17

Josephson EA, Casey EC, Waechter D, Rosneck J, Hughes JW (2006) Gender and depression symptoms in cardiac rehabilitation: women initially exhibit higher depression scores but experience more improvement. J Cardiopulm Rehabil 26(3):160–163. https://doi.org/10.1097/000

Anokye NK, Trueman P, Green C, Pavey TG, Taylor RS (2012) Physical activity and health related quality of life. BMC Public Health 12:624. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-624. Published 2012 Aug 7

Chung S, Candelaria D, Gallagher R (2022) Women’s Health-Related Quality of Life Substantially Improves With Tailored Cardiac Rehabilitation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 42(4217–226. https://doi.org/10.1097/HCR.0000000000000692

Fuentes Artiles R, Euler S, Auschra B et al (2023) Predictors of gain in exercise capacity through cardiac rehabilitation: sex and age matter. Heart Lung 62:200–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2023.08.003

Prasad DS, Das BC (2009) Physical inactivity: a cardiovascular risk factor. Indian J Med Sci 63(1):33–42

Kraus WE, Powell KE, Haskell WL et al (2019) Physical activity, all-cause and Cardiovascular Mortality, and Cardiovascular Disease. Med Sci Sports Exerc 51(6):1270–1281. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000001939

Barth J, Schneider S, von Känel R (2010) Lack of social support in the etiology and the prognosis of coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychosom Med 72(3):229–238. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181d01611

Fuochi G, Foà C (2018) Quality of life, coping strategies, social support and self-efficacy in women after acute myocardial infarction: a mixed methods approach. Scand J Caring Sci 32(1):98–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12435

Kristofferzon ML, Löfmark R, Carlsson M (2005) Coping, social support and quality of life over time after myocardial infarction. J Adv Nurs 52(2):113–124. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03571.x

Sharif F, Shoul A, Janati M, Kojuri J, Zare N (2012) The effect of cardiac rehabilitation on anxiety and depression in patients undergoing cardiac bypass graft surgery in Iran. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 12:40. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2261-12-40. Published 2012 Jun 8

Krishnamurthi N, Schopfer DW, Shen H, Whooley MA (2019) Association of Mental Health Conditions with Participation in Cardiac Rehabilitation. J Am Heart Assoc 8(11):e011639. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.118.011639

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the participants and give proper credit to the ambulatory cardiac rehabilitation personnel at Zurich University Hospital, who have made a major contribution to both availability and quality of data used for our study.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LL drafted the manuscript and contributed to analysis and interpretation of data. LJ contributed to conception and design of the study, data analysis and interpretation and critically revised the manuscript. SE contributed to conception and design of the study, data interpretation and critically revised the manuscript. RF contributed to data acquisition and critically revised the manuscript. BA and CZH contributed to data analysis and interpretation and critically revised the manuscript. DN and RvK contributed to data interpretation and critically revised the manuscript. All gave final approval to the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics committee of Canton Zurich, Switzerland (REQ-2020-0047). All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardian(s).

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

41687_2024_688_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Supplementary Material 1

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lanini, L.L.S., Euler, S., Zuccarella-Hackl, C. et al. Differential associations of sex and age with changes in HRQoL during outpatient cardiac rehabilitation. J Patient Rep Outcomes 8, 11 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41687-024-00688-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41687-024-00688-x