Abstract

Background

Finding the optimal treatment for a chronic condition can be a complex and lengthy endeavor for both the patient and the clinician. To address this challenge, we developed an “N-of-1” quality improvement infrastructure to aid providers and patients in personalized treatment decision-making using systematic assessment of patient-reported outcomes during routine care.

Methods

Using the REDCap data management infrastructure, we implemented three pediatric pilots of the Treatment Assessments in the Individual Leading to Optimal Regimens (TAILOR) tool, including children receiving early intervention, children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and children with challenging behaviors in the classroom setting. This retrospective review of data summarizes utilization and satisfaction data during our pilot experience with the tool.

Results

The three pilots included a combined total of 109 children and 39 healthcare providers, with 67 parents and 77 teachers invited to share data using brief surveys administered using TAILOR. Overall survey response rates ranged from 38% to 84% across the three pilots, with response rates notably higher among teachers as compared with parents. Satisfaction data indicated positive impressions of the tool’s utility.

Discussion

These experiences show the utility of the TAILOR framework for supporting collection and incorporation of patient-reported outcomes into the care of individuals with chronic conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Chronic diseases are increasingly prevalent [1], and managing them can be a complex endeavor for both the clinician and patient. Finding the optimal treatment plan for an individual patient often involves choosing from several alternatives in a series of trial-and-error decisions. Lack of evidence regarding the relative efficacies of each treatment, limited measures to assess response, and variability of response within populations are all serious challenges. Medical conditions with this type of profile affect patients of all ages; examples include attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, chronic musculoskeletal pain, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and sleep disturbances [2,3,4]. Patients with chronic conditions and their providers face significant challenges in identifying an optimal treatment path that is effective and consistent with the patient’s goals of care. Pediatric populations are a specifically challenging group in that individual care coordination and distribution of responsibilities are navigated within a larger group of stakeholders, often including teachers and parents [5,6,7]. In this population, roles also change with age, requiring nuanced approaches to managing chronic conditions over time.

The importance of the patient as an individual is reflected in the growing focus on patient-centered care, including the medical home model [8, 9], and patient engagement as an essential dimension of improving healthcare delivery [10,11,12]. This approach can be further strengthened by the incorporation of patient-reported outcomes and goal setting into clinical care as a way to better align treatments with the goals of care that patients identify as most important [13,14,15,16,17].

These emerging trends provided the impetus for us to develop a novel treatment strategy that focuses on the individual. Currently, most electronic health record (EHR) systems do not offer functionality for systematic, patient-driven and patient-provided outcome assessments. The EHR tools that are available for capturing patient-reported outcomes are difficult to implement, rigid in terms of functionality, and limited in terms of physicians’ ability to review data from outside the EHR. Thus, these tools are challenging to incorporate into routine care for decision-making and course correction [8, 18]. In an attempt to create a solution that goes beyond these limited EHR tools, we developed a quality improvement (QI) infrastructure to support “N-of-1” treatment decision-making using patient-reported outcomes – the Vanderbilt TAILOR tool (Treatment Assessments in the Individual Leading to Optimal Regimens). The goal of our TAILOR program is to aid providers and patients in making personalized decisions by enabling systematic, detailed, and synchronous assessment of patient-reported outcomes during routine care. This report describes our retrospective review of pilot data from application of this novel patient-centered infrastructure in three pediatric-focused implementations.

Methods

TAILOR tool overview

The TAILOR tool infrastructure was developed within REDCap, a web-based software environment providing secure and customizable data collection [19]. While each TAILOR project varies somewhat based on the needs of each clinical environment, our implementations of this tool share several key features within the tool. Each TAILOR use begins with an initial set-up discussion between a team consisting of the patient (or patient’s family) and provider to select appropriate treatments to evaluate as well as patient-centered outcomes to measure. This discussion is facilitated by an intake form within TAILOR (see Fig. 1 for an example). The team also decides on frequency and timing for outcomes data collection to optimize convenience to the patient. TAILOR allows customization of these data flows by providing several different data exchange methods. Patients may share data using a mailed link to a secure web survey, by telephone, or by responding to questions via text messaging using REDCap’s integration of Twilio, a third-party text messaging service. After this set-up discussion, the treatment evaluation period begins, with periodic collection of patient-reported outcomes through the approach selected by the patient as most convenient (e.g. text messaging; see Fig. 1 for an example). Once the data collection period concludes, patient and provider are able to review outcome data (see Fig. 2 for an example report) to identify the best approach for care moving forward.

Personalized longitudinal report of patient reported outcomes in a single patient, TAILOR Early Intervention pilot project example. Caption: This figure illustrates the longitudinal data shared by an example parent during use of the TAILOR tool while receiving Early Intervention services, showing variability in data over time and enabling the provider and patient to discuss needs for refining the treatment approach. The data includes periodic snapshots of three dimensions: the frequency of work on a skill area; parent confidence in working on the skill; and child’s success in the skill area

All iterations include a project-specific portal integrated into REDCap, containing a pre-programmed menu of possible outcome measures of interest and the frequency with which they are to be collected. The portal also includes supporting documentation (e.g., instructions for patients, materials for on-boarding new providers to use of the tool) to educate and inform both providers and patients. Each of the TAILOR pilots, discussed below, accessed the tool and supporting documentation (e.g., instructions for patients) using a shortened URL that was defined by the provider team.

Pilot implementation

We implemented pilot TAILOR projects in three pediatric outpatient settings: a clinic caring for children with known or suspected attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), a program administering early intervention (EI) services [6] to children with autism spectrum disorders or developmental delay, and a team providing support to teachers involved in the education of children with challenging behaviors (Intensive Partnership for Behavioral Intervention or IPBI). These populations were chosen due to the challenges inherent to their care management and the buy-in we were able to obtain from providers, patients, parents, and teachers. Table 1 describes each population and the approach for querying outcomes in each context, in more detail. Each pilot study iteration incorporated stakeholder perspectives and improvements in the TAILOR infrastructure. In fact, an overarching goal of these pilots was infrastructure quality improvement, aimed at continually refining the methods for facilitating collection of patient-reported outcomes and integration of these data into patient/provider decision-making.

Providers in each pilot offered individuals the option to share information using the TAILOR tool as part of usual care activities. The patient’s surrogate for data collection in these pilots included parents of children affected by a chronic condition (Early Intervention Pilot, ADHD Pilot) and teachers involved in the education of a child with challenging behaviors in the school setting (IPBI Pilot). In the ADHD Pilot only, teachers also had the opportunity to use the TAILOR tool, at parents’ discretion, to share data with healthcare providers. The frequency and length of surveys were customized within each project: parents in the ADHD project received 1–5 surveys and teachers received 1–2 surveys, over a period of 1–4 weeks; in EI, parents received surveys twice weekly for the duration of EI services, typically ranging from 3 to 6 weeks; and in the IPBI project, teachers received surveys twice weekly for the duration of their participation in the program, usually 1–2 semesters of the academic year. Questions for collection of patient-reported outcomes were drawn from validated scales in one pilot (ADHD) and from previously developed in-house assessments in two pilots (EI, IPBI).

In addition to the data on patient-reported outcomes, we also collected client and provider satisfaction data in all TAILOR pilot projects using REDCap; satisfaction surveys were typically sent 1–2 weeks after completion of the pilot implementation to providers and to parents/teachers who had used TAILOR at least once to share data. We summarized utilization and satisfaction data from the TAILOR pilots using descriptive statistics (e.g., counts, percentages).

This project was reviewed and approved by our Institutional Review Board under 45.CFR 46.102 (d) as a non-research, quality improvement project. Patients were consented as part of their clinical care outside of research activities.

Data analysis

The analysis incorporates available data from each pilot’s inception through June 2018. For each of the pilots, we extracted utilization data from REDCap, including number of participants and providers, patient outcomes of interest (EI and ADHD pilots), satisfaction data, and survey response rates. Further, as the IPBI pilot included two separate academic years, we reported utilization data for both 2016–2017 and 2017–2018.

Results

The three pilots included a combined total of 109 children and 39 healthcare providers, with 67 parents and 77 teachers invited to share data using the TAILOR infrastructure (Table 2). In the ADHD project, the majority of parents elected to include a teacher in the data collection process, with 22 teachers receiving a diagnostic and/or treatment follow-up assessment via the TAILOR tool. In the two pilots providing the option for data collection by text messaging, this mode of data collection predominated in the EI population (93%), while a relatively smaller proportion used text messaging in the IPBI cohorts (31–50%) as compared with email survey invitations.

Two of the tools (ADHD, EI) allowed for personalized selection of outcomes for periodic monitoring during treatment, while the IPBI tool collected standard outcome data for all participants. Among the 18 parents in the ADHD pilot who selected personalized outcomes for periodic monitoring, the three most-selected outcomes included classroom behavior (n = 13, 72%), sustaining attention to tasks/activities (n = 11, 61%), and completing assignments (n = 9, 50%). The three most common parent-selected areas tracked in the EI TAILOR project were communication (n = 25, 57%), challenging behavior (n = 15, 34%), and play skills (n = 6, 14%).

Overall survey response rates ranged from 38% to 84% across the three pilots. Response rates among parents ranged from 38% to 47% (ADHD and EI, respectively), while response rates for teachers varied from 79% to 84% among the different pilots in which they were included (ADHD, IPBI).

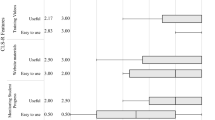

A small number of tool users answered a brief TAILOR satisfaction survey, including 12 patients/surrogates and 19 providers, representing a response rate of 11% and 49%, respectively. Responses from both user groups indicated widespread satisfaction measured across all domains, with most respondents agreeing or strongly agreeing with all statements about the tool’s utility (Table 3). Notably, the improvement in provider-patient communication endorsed by both user groups (100% and 94%) was a compelling result, reinforcing our belief that a major benefit of the tool’s usage would be an increase in informed collaborative decision-making.

Discussion

These three pilot studies demonstrated the TAILOR tool’s utility in collecting patient-reported outcomes from the “real world” while a patient tries a course of therapy. Moreover, the TAILOR tool proved valuable for facilitating communication between parents, teachers and providers regarding each patient’s symptoms and goals for treatment.

The tool also showed potential value in its method of gathering data to form a more holistic view of the patient. Not only did satisfaction data indicate the overall value of the data for helping understand the child, but the tool also proved effective in engaging the teacher, a factor significantly associated with positive outcomes in children with ADHD or autism spectrum disorders [20,21,22]. In the ADHD project, for example, teachers were regularly included in the TAILOR process by parents and frequently completed the requested outcome surveys, interestingly at a rate higher than the parents themselves. The providers in the ADHD pilot further noted anecdotally that the number of TAILOR-generated forms they received from teachers was much higher as compared to what they generally receive using a traditional process (e.g., giving the parent a form to have the teacher complete and return to the parent, or faxing the form to the child’s school). These findings again suggest the tool’s utility as a complement to usual practices. Teachers using the TAILOR tool for IPBI were similarly engaged in the data collection process with respect to children receiving intervention and support from IPBI consultants. In this case, teachers shared periodic written snapshots of classroom experiences that provided consultants with opportunities to further support the children and their teachers. Thus, our pilot experiences suggest that the TAILOR tool may be a useful strategy for adding dimensionality to patient data by facilitating information collection that reflects more than one setting and stakeholder perspective for a child.

Variability in user messaging preferences suggests that customization of the data flow experience may be an important part of future iterations. In the EI pilot, for example, parents almost exclusively preferred text messages, while teacher preferences in the IPBI pilots were distributed more evenly between email (often at their work address) or text messaging (to their personal cell phone). Future work will help us learn more about which areas of customization are most needed to ensure convenience and completeness of data collection among different populations.

The limitations of this research suggest implications for future research and clinical implementation. For example, we did not collect demographic data, and thus are not able to comment on any potential variation among possible subgroups. Also, while we observed relatively high response rates to outcome surveys among teachers, response rates were notably lower among parents, indicating that user engagement could be improved. Additional work is needed to explore ways to increase this engagement. Response rates to our satisfaction survey were low, suggesting that gathering additional formative data to further optimize the TAILOR infrastructure could be of value.

Future directions

While this report demonstrates the value of our “N-of-1” approach for use in everyday clinical practice, we believe it will prove equally beneficial in a research application. We are currently leveraging our successful pilot experiences with the TAILOR infrastructure to support development and implementation of an N-of-1 randomized controlled trial (RCT) [23] to evaluate comparative effectiveness of interventions in a chronic pain clinic population, with anticipated study start in 2019. As a part of this research process, we are also developing additional methods that will facilitate generalizability of this approach to future studies, including statistical methods for analyzing data within the individual patient as well as meta-analytic approaches for analyzing data across patients within the N-of-1 RCT. A chronic pain study will likely have different implementation needs than the pediatric pilot studies we describe above; we hope that learning how to generalize this approach to a new population will further our ability to export this technique for other uses and for use by any interested investigator. Thus, after adapting and refining TAILOR further, we hope to disseminate this infrastructure to facilitate N-of-1 studies and the collection of patient-reported outcomes. Our future aim is to make N-of-1 research protocols easy to implement within a range of clinical settings and to further strengthen our collective capacity to explore personalized medicine hypotheses.

Conclusions

These pilot experiences show the utility of the TAILOR approach for supporting collection and incorporation of patient-reported outcomes into the care of individuals with chronic conditions. The growing recognition of the importance of patient-reported outcomes and emergence of technologies to support convenient data collection provide excellent support for the advancement of N-of-1 methods for personalized patient care [24, 25].

Abbreviations

- ADHD:

-

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

- EHR:

-

Electronic health record

- EI:

-

Early Intervention

- IPBI:

-

Intensive Partnership for Behavioral Intervention

- REDCap:

-

Research electronic data capture

- TAILOR:

-

Treatment Assessments in the Individual Leading to Optimal Regimens

References

Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators. (2015). Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet, 386(9995), 743–800 PMCID: PMC4561509.

Gabler, N. B., Duan, N., Vohra, S., & Kravitz, R. L. (2011). N-of-1 trials in the medical literature: A systematic review. Med Care, 49(8), 761–768.

Scuffham, P. A., Nikles, J., Mitchell, G. K., Yelland, M. J., Vine, N., Poulos, C. J., Pillans, P. I., Bashford, G., del Mar, C., Schluter, P. J., & Glasziou, P. (2010). Using N-of-1 trials to improve patient management and save costs. J Gen Intern Med, 25(9), 906–913 PMCID: PMC2917656.

Mitchell, G. K., Hardy, J. R., Nikles, C. J., Carmont, S.-A. S., Senior, H. E., Schluter, P. J., Good, P., & Currow, D. C. (2015). The effect of methylphenidate on fatigue in advanced cancer: An aggregated N-of-1 trial. J Pain Symptom Manag PMID: 25896104.

Dang, M. T., Warrington, D., Tung, T., Baker, D., & Pan, R. J. (2007). A school-based approach to early identification and Management of Students with ADHD. J Sch Nurs, 23(1), 2–12.

Adams, R. C., Tapia, C., & Disabilities TC on CW. (2013). Early intervention, IDEA part C services, and the medical home: Collaboration for best practice and best outcomes. Pediatrics., 132(4), e1073–e1088 PMID: 24082001.

Fiks, A. G., Hughes, C. C., Gafen, A., Guevara, J. P., & Barg, F. K. (2011). Contrasting parents’ and pediatricians’ perspectives on shared decision-making in ADHD. Pediatrics., 127(1), e188–e196 PMCID: PMC3010085.

Bates, D. W., & Bitton, A. (2010). The future of health information technology in the patient-centered medical home. Health Aff, 29(4), 614–621.

Disabilities C on CW. (2005). Care coordination in the medical home: Integrating health and related systems of care for children with special health care needs. Pediatrics., 116(5), 1238–1244 PMID: 16264016.

Capko, J. (2014). The patient-centered movement. J Med Pract Manage, 29(4), 238–242 PMID: 24696963.

Irizarry, T., Dabbs, A. D., & Curran, C. R. (2015). Patient portals and patient engagement: A state of the science review. J Med Internet Res, 17(6), e148.

Gerardi, C., Roberto, A., Colombo, C., & Banzi, R. (2016). Patient-reported outcomes: Nothing without engagement. Acta Oncol, 55(12), 1494–1495 PMID: 27553172.

Forsberg, H. H., Nelson, E. C., Reid, R., Grossman, D., Mastanduno, M. P., Weiss, L. T., Fisher, E. S., & Weinstein, J. N. (2015). Using patient-reported outcomes in routine practice: Three novel use cases and implications. J Ambul Care Manage, 38(2), 188–195 PMID: 25748267.

Haywood, K. L., Staniszewska, S., & Chapman, S. (2012). Quality and acceptability of patient-reported outcome measures used in chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME): A systematic review. Qual Life Res, 21(1), 35–52.

Marshall, S., Haywood, K., & Fitzpatrick, R. Impact of patient-reported outcome measures on routine practice: A structured review. J Eval Clin Pract, 12(5), 559–568.

Camuso, N., Bajaj, P., Dudgeon, D., & Mitera, G. (2016). Engaging patients as partners in developing Patient-Reported Outcome Measures in cancer-a review of the literature. Support Care Cancer, 24(8), 3543–3549 PMID: 27021391.

Jones, P. W., Rennard, S., Tabberer, M., Riley, J. H., Vahdati-Bolouri, M., & Barnes, N. C. (2016). Interpreting patient-reported outcomes from clinical trials in COPD: A discussion. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis, 11, 3069–3078 PMCID: PMC5153282.

Health Information Technology and the Medical Home. Pediatrics. 2011;127(5):978–982. PMID: 21518710.

Harris, P. A., Taylor, R., Thielke, R., Payne, J., Gonzalez, N., & Conde, J. G. (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform, 42(2), 377–381 PMCID: PMC2700030. PMCID: PMC2700030.

Dickson, K. S., Suhrheinrich, J., Rieth, S. R., & Stahmer, A. C. (2018). Parent and teacher concordance of child outcomes for youth with autism Spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord, 48(5), 1423–1435 PMCID: PMC5889953.

Moldavsky, M., & Sayal, K. (2013). Knowledge and attitudes about attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and its treatment: The views of children, adolescents, parents, teachers and healthcare professionals. Curr Psychiatry Rep, 15(8), 377 PMID: 23881709.

Kildea, S., Wright, J., & Davies, J. (2011). Making sense of ADHD in practice: A stakeholder review. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry, 16(4), 599–619 PMID: 21429978.

Kravitz RL, Duan N. Design and implementation of N-of-1 trials: A User’s guide [internet]. 2014 [cited 2018 Jul 19]. Available from: https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/n-1-trials_research-2014-5.pdf

Kravitz, R. L., Schmid, C. H., Marois, M., Wilsey, B., Ward, D., Hays, R. D., Duan, N., Wang, Y., MacDonald, S., Jerant, A., Servadio, J. L., Haddad, D., & Sim, I. (2018). Effect of Mobile device–supported single-patient multi-crossover trials on treatment of chronic musculoskeletal pain: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med, 178(10), 1368–1377.

Byrom, B., Doll, H., Muehlhausen, W., Flood, E., Cassedy, C., McDowell, B., Sohn, J., Hogan, K., Belmont, R., Skerritt, B., & McCarthy, M. (2018). Measurement equivalence of patient-reported outcome measure response scale types collected using bring your own device compared to paper and a provisioned device: Results of a randomized equivalence trial. Value Health, 21(5), 581–589.

NICHQ.Org | NICHQ Vanderbilt Assessment Scales [Internet]. [cited 2015 Apr 28]. Available from: http://www.nichq.org/childrens-health/adhd/resources/vanderbilt-assessment-scales

Acknowledgments

The authors express their appreciation to our pilot collaborators, including Dr. Rosemary Hunter and the residents of Vanderbilt Children’s Hospital Primary Care Clinic and our Vanderbilt Treatment and Research Institute for Autism Spectrum Disorders (TRIAD) colleagues. We also thank Meredith O’Brien and Nancy Kennedy for their aid in preparing the manuscript for publication.

An earlier subset of TAILOR results was presented as a poster (Roane JT, Jerome R, Juárez P, Loring W, Stainbrook AJ. Feasibility pilot of web-based surveys to enhance monitoring of behavior change patterns. Poster presented at Tennessee Applied Behavior Analysis Meeting (Nashville, TN), October 26-28, 2017).

Funding

The project described was supported by CTSA award No. UL1 TR002243 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent official views of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences or the National Institutes of Health.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RNJ contributed to the concept and design of TAILOR, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting and revising the work. JMP contributed to the concept and design of TAILOR, interpretation of data, and drafting the work. TLE participated in the concept and design of TAILOR, interpretation of data, and revising the work for critical intellectual content. ABD contributed to the design of TAILOR, acquisition and analysis of data, and drafting the work. DC contributed to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data and drafting and revising the work. SLV contributed to the concept and design of TAILOR, interpretation of data, and revising the work for critical content. GB contributed to the conception and design of the program and revising the work for critical intellectual content. PH contributed to the concept and design of the program, interpretation of data, and revision of the work for critical content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Vanderbilt Institutional Review Board (IRB project #151906) reviewed this quality improvement project and determined the project does not qualify as “research” per 45 CFR §46.102(d).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Jerome, R.N., Pulley, J.M., Edwards, T.L. et al. We’re not all cut from the same cloth: TAILORing treatments for children with chronic conditions. J Patient Rep Outcomes 3, 25 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41687-019-0117-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41687-019-0117-2