Abstract

Background

This study evaluated the prevalence, predictors and effects of Shift Work Sleep Disorder (SWSD) among nurses in a Nigerian teaching hospital.

Methods

Eighty-eight nurses (44 each from the pool of shift and non-shift nurses), who emerged by simple random sampling, participated in the study. Socio-demographic data and health complaints were obtained with questionnaires. Each participant was assessed with Epworth sleepiness scale (ESS), insomnia severity index (ISI) and sleep log, while SWSD cases were ascertained by applying the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD-2) criteria. Body mass index, blood pressure, body temperature and salivary cortisol levels were also determined.

Results

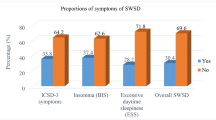

Generally, results showed that the shift group; comprising of shift nurses, recorded higher values of biophysical profiles and more health complaints than the non-shift group (control); comprising of non-shift nurses. Also, 19 (43.2%) of the shift nurses fulfilled the criteria for SWSD, on this basis, the shift group was divided into two: SWSD (n = 19) and No SWSD (n = 25). And within the shift group, the SWSD group had higher systolic (p = 0.014), diastolic (p = 0.012), and mean arterial (p = 0.009) blood pressures; they also recorded higher temperature (p = 0.001), higher salivary cortisol levels (p = 0.027) and more health complaints.

Conclusion

The results of this study indicate that rotating shift work among nurses is associated with increased level of health complaints and physiologic indices of stress as well as sleep impairment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Shift work is an employment practice designed to make use of, or provide service across, all 24 h of the clock each day of the week (often abbreviated as 24/7). The practice typically sees the day divided into shifts and sets periods of time during which different groups of workers perform their duties. The term “shift work” includes both long-term night shifts and work schedules in which employees change or rotate shifts (U.S. Congress Office of Technology Assessment 1991; Institute for Work and Health; 2014; Grosswald 2004). In Nigeria, shiftwork is prevalent among factory workers and nurses (Omoarukhe 2012). Nurses engage in shift work schedule as a means of providing uninterrupted and round-the-clock care to patients in the hospital (Isah et al. 2008). In the Nigerian hospital under study i.e. Federal teaching hospital, Ido-Ekiti (FETHI) the shift arrangement in the work schedule of nurses involves the morning shift (8 am–4 pm), afternoon shift (1 pm–8 pm) and night shift (8 pm–8 am). While some nurses work on non-shift basis (permanent morning), some work on rotating shift basis; thereby alternating between morning, afternoon and night shifts.

Shift work sleep disorder (SWSD) is a sleep disorder that is typified by sleepiness and insomnia, which can be attributed to an individual’s work schedule (Flo et al., 2012). And according to the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD-3), SWSD is characterized by insomnia or sleepiness that occurs in association with shift work (American Academy of Sleep Medicine 2014). The diagnostic criteria for SWSD, as defined by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM)’s International Classification of Sleep Disorders-3 (ICSD-3) (American Academy of Sleep Medicine 2014) include: (a) There is a report of insomnia and/or excessive sleepiness, accompanied by a reduction of total sleep time, which is associated with a recurring work schedule that overlaps the usual time for sleep; (b) the symptoms have been present and associated with the shift work schedule for at least 3 months; (c) sleep log and actigraphy monitoring (where possible and preferably with concurrent light exposure measurement) for at least 14 days (work and free days) demonstrate a disturbed sleep and wake pattern; (d) the sleep and/or wake disturbance are not better explained by another current sleep disorder, mental disorder, medication use, poor sleep hygiene, or substance use disorder. While the criteria in the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM)’s International Classification of Sleep Disorders-2 (ICSD-2) (American Academy of Sleep Medicine 2005) include: (i) complaints of insomnia or excessive sleepiness temporally associated with a recurring work schedule in which work hours overlap with the usual time for sleep, (ii) symptoms must be associated with the shift work schedule over the course of at least 1 month, (iii) sleep log or actigraphic monitoring for ≥7 days demonstrates circadian and sleep-time misalignment; (iv) sleep disturbance is not better explained by another sleep disorder, mental disorder, a medical or neurological disorder, medication use or substance use disorder (American Academy of Sleep Medicine 2005). The total daily sleep time is usually shortened and sleep quality is less in those who work night shifts compared to those who work day shifts (Liira et al. 2015). Many of the people suffering from SWSD remain undiagnosed and untreated, the consequences of which include: reduced productivity, lowered cognitive performance, increased likelihood of accidents, high risk of morbidity and mortality and decreased quality of life (Knutson 2003). There is need therefore, to study SWSD in relation to its prevalence, predictors and possible effects, with a view to providing useful recommendations to shift-workers and their employers on the effective coping strategies with shift work schedules. Also, emerging evidence raises serious concern about the potential impact of SWSD on health outcomes. The data generated from this study has the potential of driving new guidelines and directing policies regarding shiftwork practices in Nigeria.

Methods

Participant

Ethical clearance was obtained from Ethics and Research Committee of FETHI, while written informed consent was obtained from all the participants. The participants were members of FETHI nursing staff between the ages of 22–45 years. Eighty-eight (88) of them drawn into two groups of forty-four (44) each; shift group and non-shift group (control) participated in this study. The shift group comprised of nurses who worked on shift basis (rotating shift), while the non-shift group comprised of nurses who worked between 8 am and 4 pm on working weekdays (Monday to Friday). The participants emerged as follows: out of a total nursing staff population of one hundred and fifty-nine (159), the total number of nurses who work on non-shift basis is sixty-eight (68), while the remaining nurses (91) work on shift basis. Using FETHI nursing staff register, numbers were assigned to the nurses; the non-shift nurses were assigned numbers ranging from 1 to 68, while the shift nurses were assigned numbers ranging from 1 to 91. Forty-four (44) random numbers within the range of 1 to 68 were then electronically generated, the corresponding numbers (on FETHI non-shift nursing staff register) to the numbers so generated were the non-shift nurses recruited into this study and this represented the non-shift group. Again, forty-four (44) random numbers, this time within the range of 1 to 91 were electronically generated and the corresponding numbers (on FETHI non-shift nursing staff register) to the numbers so generated were the shift nurses recruited into this study, this represented the shift group. Nursing mothers and individuals with history of chronic medical illnesses, such as: Diabetes Mellitus; Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD); Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome (OSAS); Central Sleep Apnea Syndrome (CSAS); Hypertensive Heart Disease; Cancers, and psychiatric diseases, which can cause sleep disruption were excluded. Also excluded were individuals who were on drugs that alter sleep pattern such as the benzodiazepines, barbiturates, antihistamines, quinazolinones, antidepressants, antipsychotics and melatonin.

Measurements

Anthropometric measurements

The height and weight of each participant were measured by the investigators and trained research assistants in accordance with the World Health Organization (WHO) multinational monitoring of trends and determinants in cardiovascular disease criteria (Böthig 1989). To measure height, the participant was asked to take off his/her hats or head ties and shoes, stand with his/her back to a vertical rigid measure calibrated to the nearest 0.1 centimeter (cm). They were asked to hold their heads and look straight in front of them. A flat rule was placed on the highest point on the participant’s head (scalp) at right angles to the vertical rule. The point at which the hand-held rule touched the vertical rule was the participant’s height. To measure weight, the weighing scale was placed on a hard, straight surface, and the participants were asked to take off their shoes and empty their pockets and stand on the weighing scale while they looked straight ahead of them. Height and weight were measured to the nearest 0.1 cm and 0.1 kilogram (kg), respectively. Body mass index (BMI), a measure of body adiposity, was calculated using the formula weight (kg) divided by the square of height (meter squared; m2) (Keys et al. 1972).

Blood pressure measurement

Blood pressure measurements were done with digital sphygmomanometer of appropriate cuff size per participant. The participants were asked to sit and take a rest of at least 5 min. The cuff of the sphygmomanometer was then tied round the left arm (without any intervening clothing) and with the lower edge of the cuff an inch above the cubital fossa of flexed arm of the subject, the cuff is inflated and measurement taken. Measurements were taken between 8 am and 9 am.

Measurement of body temperature

The body temperature of each participant was measured at the axilla, by placing the digital thermometer in a central position (in the armpit), the arm is then adducted close to the chest wall and the thermometer is left in this position until it beeps. The displayed value is then recorded. Measurements were taken between 8 am and 9 am.

Assessment of sleepiness

Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) is an effective instrument used to measure average daytime sleepiness. The ESS differentiates between average sleepiness and excessive daytime sleepiness that requires intervention. The individual self-rates his/her likelihood of dozing in eight different situations. Scoring of the answers is 0–3, with 0 being “would never doze” and 3 being “high chance of dozing”. A sum of 11 or more from the eight individual scores reflects above normal daytime sleepiness and need for further evaluation (Johns 1991). The validity and reliability of ESS has been tested in different groups of individuals across the healthcare continuum. It has also been used previously among populations in Nigeria (Drager et al. 2010; Ozoh et al. 2013; Obaseki et al. 2014).

Assessment of insomnia

This was done by using the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI). ISI is a standardized and validated tool for assessing insomnia (Bastien et al. 2001). The ISI has seven questions with scores for each question ranging from 0 to 4. The scores for the seven answers were added up to get a total score. Total score categories of ISI are: 0–7 = No clinically significant insomnia, 8–14 = Sub threshold insomnia, 15–21 = Clinical insomnia (moderate severity), 22–28 = Clinical insomnia (severe). A score of 10 or more was used as the cut off for insomnia in this study.

Sleep pattern monitoring

Participants’ sleep pattern was monitored using a 30-day sleep log. The sleep log was filled by participant having been instructed on how to use it. Important components of the sleep log included time of retiring to bed, estimated time taken to fall asleep, time of final awakening, as well as the time/length of in-between awakening(s) before the final awakening. Total sleep duration (nocturnal and daytime) as well as sleep efficiency were calculated from the sleep log as follows;

-

Total time in bed (TB) in minutes. = time between bedtime and rise time.

-

Total time awake (TA) in minutes = total time of in-between awakening(s) before the final awakening.

-

Total sleep time (TS) in minutes = (TB) – (TA)

-

Sleep efficiency (E) = (TS) / (TB) × 100%.

Salivary cortisol analysis

Samples of participants’ saliva were collected between 8 am and 9 am using a salivette. Participants were asked not to eat before salivary collection and they were asked to do gentle rinsing of their mouths with water, after which 4 ml of saliva was collected into a labelled salivette. The analysis of the saliva samples was done at the chemical pathology laboratory of FETHI, using enzyme immunoassay testing; the principle of which followed the competitive binding scenario.

Statistical analysis

All data collected were entered into and analyzed with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) for windows, version 21.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY). Means, standard deviations, proportions and percentages were determined as appropriate. Tests of significance for differences and associations were done using Pearson’s Chi-Square and Yate’s continuity corrections were carried out where applicable. Student’s independent t-test was used for mean comparisons. P-values of less than 0.05 were taken to be statistically significant. A binary logistic regression was run to estimate the adjusted odd ratios for all the identified predictors of SWSD.

Results

Comparison of socio-demographic characteristics between the SWSD, no SWSD and non-shift groups

The shift group was divided into two groups; SWSD and No SWSD groups, based on the assessment of SWSD or not among the participants. Comparing the groups; SWSD versus No SWSD, SWSD versus controls, and No SWSD versus control were comparable across all socio-demographic characteristics as seen in Table 1. However, there was no significant difference in all the compared parameters (Table 1).

Comparison of health complaints and occupational accident between the SWSD, no SWSD and non-shift groups

Participants in the SWSD group were more likely to complain of frequent headaches (p = 0.045), generalized muscle ache (p = 0.005) and lack of concentration (p = 0.003) compared with the No SWSD group. The SWSD group, compared with the control group, was more likely to report frequent headaches (p = 0.003), generalized muscle ache (p = 0.003), lack of concentration (p < 0.001), fatigue (p = 0.029), menstrual irregularities (p = 0.043), and needle stick injury (p = 0.012). The No SWSD group, compared with the control group, were more likely to report menstrual irregularities (p = 0.039) (Table 2).

Comparison of anthropometric and biophysical profiles between SWSD, no SWSD and non-shift groups

The groups show no significant difference in their BMI scores and pulse pressure. However, the SWSD group compared with the No SWSD group had higher systolic blood pressure (p = 0.014), diastolic blood pressure (p = 0.012) and mean arterial blood pressure (p = 0.009). The SWSD group had higher temperature (°C) than the No SWSD group (p < 0.001) and the control group (p < 0.001). The No SWSD group had higher temperature than the control group (p = 0.001). The SWSD group had higher cortisol level (ng/ml) than the No SWSD group (p = 0.027) and the control group (p < 0.004) (Table 3).

Comparison of sleep parameters between SWSD, no SWSD and non-shift groups

The SWSD group had lower nocturnal sleep duration than the control group (p < 0.001), higher daytime sleep duration than the control group (p < 0.001), lower sleep efficiency than the No SWSD group (p = 0.002), higher ESS scores than both the No SWSD group and the control group (p < 0.001), higher proportion of participants reporting excessive daytime sleepiness than the No SWSD and control groups(p < 0.001), higher ISI score than the control group (p = 0.028), and higher proportion of participants reporting insomnia than the control group (p = 0.088). The No SWSD group, compared with the control group, had lower nocturnal sleep duration (p < 0.001), higher daytime sleep duration (p < 0.001) and had no report of excessive daytime sleepiness (p = 0.043) (Table 4).

Logistic regression of the predictors of shift work sleep disorder among the shift subjects

Table 5 shows the predictors of SWSD among the shift subjects on bivariate analysis. However, none of these factors independently predicted SWSD upon regression analysis (Table 5).

Discussion

In this study, all the participants essentially were in the same age range, with the shift group having a mean age of 35.7 ± 4.6 while the controls had a mean age of 36.7 ± 4.8. No significant difference existed between the groups on account of age and sex. However, majority of the participants in both groups were female. The female gender dominance in the study population is consistent with the finding of Ulrich (2010). Although this study found no association between gender and SWSD, this is contrary to the findings of lower risk for the female gender reported by Flo et al., 2012. The dominant ethnicity of the participants in this study was Yoruba, understandably so, since the study was carried out at a location in Nigeria that is dominated by the Yoruba ethnic nationality (Falola and Heaton 2008), even though no statistically significant difference was observed in the representation of ethnicity in the study groups. The prevalence of substance use was low across the groups and it was in the form of smoking, alcohol, coffee and kola nut consumption. The shift group reported a higher proportion of participants with substance use. This is consistent with the findings of Lasebikan and Oyetunde 2012, who reported that shift nurses are more involved in substance use than non-shift nurses. This may be borne out of repeated need to stay awake and be alert on duty during the natural sleep period.

Health complaints in the form of frequent headaches, generalized muscle aches, lack of concentration, fatigue, backache, aches in the feet, indigestion and menstrual irregularities cut across the shift and non-shift groups. On a general note, the shift group, compared to the control group had higher proportion of participants reporting symptoms on each of the afore-listed health complaints, however there was significant differences only in the reports of lack of concentration, fatigue, and menstrual irregularities. Within the shift group, reports of health complaints were most likely to be present in the SWSD group. Previous studies have reported similar pattern in the report of health problems among shift workers (Costa 1994; Knutson 2003). The reason for these health complaints may be due to the various circadian dysrhythmias associated with shift duty; for example circadian disruption was reported to be associated with fatigue (Cole et al. 1990), digestive disorders (Lennernäs et al. 1994) and cardiovascular diseases (Knutsson and Bøggild 2000). We also found out that a higher proportion of the shift nurses reported occupational accident in the form of needle stick injury compared with the non-shift nurses, also more shift nurses in the SWSD group reported needle stick injury than the shift nurses without SWSD; this points to the vulnerability of the shift nurses with SWSD. The occurrence of needle stick injury is of note, especially as human immunodeficiency virus and other blood-borne infections may be transmitted through such means (Steven 2007). Although this study did not consider the risk of motor vehicle accidents between participants in the two groups of study, there has been documentation of incidents of motor vehicle accidents among night shift workers. A recent study in Iran made an alarming discovery of increased motor vehicle accidents among night shift workers (Saadat et al. 2018).

In the present study, both the shift and control groups showed no significant difference on account of their mean BMI scores. Also, the three groups of SWSD, No SWSD and non-shift showed no significant difference when assessed on the basis of their BMI score. However, a downward trend in the BMI scores was observed from SWSD to No SWSD to the non-shift groups (Table 3). Studies by Scheer et al. (2009); Delezie and Challet (2011), had reported higher BMI scores among shift workers. The exact mechanisms linking shift work to higher BMI scores are still developing, but proposed pathways include reduced leisure time for physical activity, difficulty in maintaining a healthy diet or increased consumption of energy-dense foods to combat fatigue, and reduced quality and quantity of sleep (Antunes et al. 2010).

In the present study, there were no significant differences in the blood pressure indices (systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, mean arterial blood pressure and pulse pressure) between the shift nurses and the nurses who work non shift. This is in tandem with the study of Sfreddo et al. (2010), which found no association between shift work and the incidence of hypertension. However, McCubbin et al. (2010), reported a direct relationship between working night shift and blood pressure dysregulation, especially in individuals with positive family history of hypertension. The study by McCubbin et al. (2010), further revealed that stress caused by shift work may have adverse effects on the cardiovascular system both through direct mechanisms as well as by indirect influences. The observation, in this study, of insignificant difference between the shift and non-shift groups on account of blood pressure parameters, may be due to the fact that the participants in this study fall under the age group which have lower tendency for hypertension in addition to the fact that the participants are medically-inclined and as such may have taken necessary precautionary measures to prevent high blood pressure.

We observed a statistically significantly higher mean body temperature among the shift nurses as compared to the nurses who work non-shift (controls). Comparison between the three groups of SWSD, No SWSD and non-shift group also show significant differences in mean body temperature (°C), with the SWSD group recording the highest mean body temperature and the non-shift recording the least (Table 3). Study by Colquhoun and colleague also found a higher body temperature among shift workers (Colquhoun and Edwards 1970).

The secretion of cortisol (a major glucocorticoid secreted by the adrenal cortex) follows a diurnal rhythm, with the highest in the morning and the lowest in the night. In addition, the secretion of cortisol increases in stressful situations (Smith et al. 2009). In this study, we found a direct relationship between cortisol level and working on shift basis; higher cortisol levels were recorded among nurses who work on shift basis than those who work non-shift. It is also note-worthy that even among the shift group, the SWSD group recorded a significantly higher cortisol level. This higher cortisol level among the shift group may partly explain some of the symptoms/complaints reported by the nurses who work rotating shift.

The mean nocturnal sleep duration (over a 30-day period) for shift nurses was significantly lower than that of the nurses in the control group. Within the shift group, the SWSD group had lower mean nocturnal sleep duration than the No SWSD group (Table 4). Also, the mean daytime sleep duration (over a 30-day period) for shift nurses was significantly higher than that of the controls group, and within the shift group, the SWSD group recorded a higher mean daytime sleep duration (Table 4). It can be inferred from this that the shift nurses had inadequate nighttime sleep duration (worse among the SWSD group) which they try to make up for in the day; this is a sleep time misalignment of some sort. The mean ESS and ISI scores were significantly higher among the shift group than the controls. Also a significantly higher proportion of the shift nurses had excessive daytime sleepiness; these, coupled with a better sleep efficiency among the non-shift nurses point to the existence of SWSD among the shift nurses. Although individuals with symptoms and history suggestive of CKD, OSAS and CSAS were exempted from this study, it is important to note that both OSAS and CSAS are implicated in excessive daytime sleepiness and nighttime insomnia (American Academy of Sleep Medicine 2014). In addition, association has been established between CKD and OSAS (Nigam et al. 2017), and also between CKD and CSAS (Nigam et al. 2016). Previous studies had reported a prevalence level of 10% in a community-based sample (Drake et al. 2004), while Waage et al. (2009), reported a prevalence of 23.3% among oil rig workers. These figures are lower than what was reported by Flo et al. (2012a, 2012b); 43.3% (among nurses) and what we found out in this current study; 43.2%. It is instructive to know that these high prevalence levels were both reported among nurses.

Bivariate analysis showed the predictors of SWSD among the shift nurses and the identified predictors were: headache, muscle ache, lack of concentration, high salivary cortisol level, high diastolic blood pressure and low sleep efficiency. On logistic regression analyses however, these factors did not independently predict SWSD.

Limitations

The fact that none of the identified predictors of SWSD independently predicted the condition may be a limitation of some sort of this study. Also, by conducting this study in a region of Nigeria that is dominated by a particular tribe, the study was rubbed of variability. Therefore, a larger and more varied study population and variable testing may be necessary in future studies. Another shortcoming of this study is that the study lasted a month, hence sleep monitoring was done for 30 days and ICSD-2 diagnostic criteria was applied, thereby limiting the application of ICSD-3 (American Academy of Sleep Medicine 2014). In addition, actigraph monitoring was not done, but a 30-day sleep log was employed. However, by using standardized and validated instruments and by recruiting heterogenous subjects in a profession that is almost entirely homogenous, we sought to bring strength to this study.

Conclusion

Evidence from this study suggest that rotating shift work among nurses is associated with increased level of health complaints and physiologic indices of stress as well as sleep impairment. The prevalence of SWSD among shift nurses in this study was 43.2%. The factors that predicted SWSD in the study sample were headache, muscle ache, lack of concentration, high salivary cortisol level, high diastolic blood pressure and low sleep efficiency.

Abbreviations

- CKD:

-

Chronic Kidney Disease

- COPD:

-

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- CSAS:

-

Central Sleep Apnea Syndrome

- ESS:

-

Epworth Sleepiness Scale

- FETHI:

-

Federal Teaching Hospital, Ido-Ekiti

- ICSD-2:

-

International Classification of Sleep Disorders-2nd edition

- ICSD-3:

-

International Classification of Sleep Disorders-3rd edition

- ISI:

-

Insomnia Severity Index

- OSAS:

-

Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome

- SWSD:

-

Shift Work Sleep Disorder

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM). International classification of sleep disorders, revised: Diagnostic and coding manual. 2nd edn. (ICSD-2). Westchester: AASM; 2005.

American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM). In: Darien IL, editor. International classification of sleep disorders. 3rd ed. United States: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014.

Antunes LC, Levandovski R, Dantas G, Caumo W, Hidalgo MP. Obesity and shift work: Chronobiological aspects. Nutr Res Rev. 2010;23(1):155–68.

Bastien CH, Vallieres A, Morin CM. Validation of the insomnia severity index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2:297–307.

Böthig S. WHO MONICA Project: objectives and design. Int J Epidemiol. 1989;18(3):S29–37.

Cole RJ, Loving RT, Kripke DF. Psychiatric aspects of shiftwork. Occup Med. 1990;5:301–14.

Colquhoun WP, Edwards RS. Circadian rhythms of body temperature in shift Workers at a Coalface. Br J Ind Med. 1970;27(3):266–72.

Costa G. The impact of shift and night work on health. Appl Ergon. 1994;27(1):922.

Delezie J, Challet E. Interactions between metabolism and circadian clocks: reciprocal disturbances. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1243:30–46.

Drager LF, Genta PR, Pedrosa RP, Nerbass FB, Gonzaga CC, Krieger EM, et al. Characteristics and predictors of obstructive sleep apnea in patients with systemic hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105(8):1135–9.

Drake CL, Roehrs T, Richardson G, Walsh JK, Roth T. Shift work sleep disorder: prevalence and consequences beyond that of symptomatic day workers. Sleep. 2004;27:1453–62.

Falola T, Heaton MM. A history of Nigeria. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2008. p. 23. ISBN 0-521-68157-X

Flo E, Pallesen S, Magerøy N, Moen BE, Grønli J. Shift work disorder in nurses assessment, prevalence and related health problems. PLoSONE. 2012b;7(4):e33981.

Flo E, Pallesen S, Magerøy N, Moen BE, Grønli J, Nordhus IH, Bjorvatn B. Shift Work Disorder in Nurses – Assessment, Prevalence and Related Health Problems. PLoS One. 2012a;7(4):e33981.

Grosswald B. The effects of shift work on family satisfaction. Families in Society. 2004;85(3):413–24.

Institute for Work & Health, Ontario, Canada. Fact Sheet, Shiftwork (PDF). Retrieved. 2014: 09-25.

Isah EC, Iyamu OA, Imoudu GO. Health effects of night shift duty on nurses in a university teaching hospital in Benin. Nigeria: Niger J Clin Pract. 2008;11(2):144–8.

Johns M. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14:540–5.

Keys A, Fidanza F, Karvonen MJ, Kimura N, Taylor HL. Indices of relative weight and obesity. J Chronic Dis. 1972;25:329–43.

Knutson A. Health disorders of shift workers. Occup Med (Lond). 2003;53:103–8.

Knutsson A, Bøggild H. Shiftwork and cardiovascular disease: review of disease mechanisms. Rev Environ Health. 2000;15:359–72.

Lasebikan VO, Oyetunde MO. Burnoutamong nurses in a Nigerian general hospital: prevalence and associated factors. ISRN Nurs. 2012; https://doi.org/10.5402/2012/402157.

Lennernäs M, Hambraeus L, Åkerstedt T. Nutrient intake in day and shift workers. Work Stress. 1994;8:332–42.

Liira J, Verbeek JH, Costa G, Driscoll TR, Sallinen M, Isotalo LK, Ruotsalainen JH. “Pharmacological interventions for sleepiness and sleep disturbances caused by shift work” The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 8. JAMA. 2015;313(9):961–2.

McCubbin JA, Pilcher JJ, Moore DD. Blood pressure increases during a simulated night shift in persons at risk for hypertension. Int J Behav Med. 2010;17(4):314–20.

Nigam G, Camacho M, Chang ET, Riaz M. Exploring sleep disorders in patients with chronic kidney diseases. Nat Sci Sleep. 2018;10:35–43.

Nigam G, Pathak C, Riaz M. A systematic review of central sleep apnea in adult patients with chronic kidney disease. Sleep Breath. 2016;20(3):957–64.

Obaseki D, Kolawole B, Gomerep S, Obaseki J, Abidoye I, Ikem R, et al. Pre- valence and predictors of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome ina sample of patients with type2 Diabetes Mellitus in Nigeria. Niger Med J. 2014;55(1):24–8.

Omoarukhe, Omowumi. Management of Swift Work in Nigeria and its implications for labour – management relations, Green Thesis. 2012.

Ozoh O, Okubadejo N, Akanbi M, Dania M. High-risk of obstructive sleep apnea and excessive daytime sleepiness among commercial intra-city drivers in Lagos metropolis. Niger Med J. 2013;54(4):224–9.

Saadat S, Karbakhsh M, Saremi M, Alimohammadi I, Ashayeri H, Fayaz M, Sadeghian F, Rostami R. A prospective study of psychomotor performance of driving among two kinds of shift work in Iran. Electron Physician. 2018;10:6417–25. https://doi.org/10.19082/6417.

Scheer FA, Hilton MF, Mantzoros CS, Shea SA. Adverse metabolic and cardiovascular consequences of circadian misalignment. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106(11):4453–8.

Sfreddo C, Fuchs SC, Merlo ÁR, Fuchs FD. Shift work is not associated with high blood pressure or prevalence of hypertension. PLoS One. 2010;5(12):e15250.

Smith JL, Gropper SA, Groff J. Advanced nutrition and human metabolism. Belmont: Wadsworth Cengage Learning; 2009. p. 247. ISBN 0-495-11657-2

Steven B. Environmental and occupational medicine. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. p. 745. ISBN 978-0-7817-6299-1

U.S. Congress Office of Technology Assessment. Biological Rhythms: Implications for the Worker. 1991.

Ulrich B. Gender diversity and nurse-physician relationships. Virtual Mentor. 2010;12:41–5.

Waage S, Moen BE, Pallesen S, Eriksen HR, Ursin H, Akerstedt T, et al. Shift work disorder among oil rig workers in the North Sea. Sleep. 2009;32:558–65.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study is not publicly available due to confidentiality but can be made available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BAF, AOA and MBF made significant contributions to conception, design, experimentation, acquisition and interpretation of data and writing of manuscript. QKA, AMO and JGO made substantial contribution in interpretation of data and revising the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent for publication

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Competing interests

The authors of this manuscript declare no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Fadeyi, B.A., Ayoka, A.O., Fawale, M.B. et al. Prevalence, predictors and effects of shift work sleep disorder among nurses in a Nigerian teaching hospital. Sleep Science Practice 2, 6 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41606-018-0027-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41606-018-0027-x