Abstract

Offshore wind farms (OWFs) have received widespread attention for their abundant unexploited wind energy potential and convenient locations conditions. They are rapidly developing towards having large capacity and being located further away from shore. It is thus necessary to explore effective power transmission technologies to connect large OWFs to onshore grids. At present, three types of power transmission technologies have been proposed for large OWF integration. They are: high voltage alternating current (HVAC) transmission, high voltage direct current (HVDC) transmission, and low-frequency alternating current (LFAC) or fractional frequency alternating current transmission. This work undertakes a comprehensive review of grid connection technologies for large OWF integration. Compared with previous reviews, a more exhaustive summary is provided to elaborate HVAC, LFAC, and five HVDC topologies, consisting of line-commutated converter HVDC, voltage source converter HVDC, hybrid-HVDC, diode rectifier-based HVDC, and all DC transmission systems. The fault ride-through technologies of the grid connection schemes are also presented in detail to provide research references and guidelines for researchers. In addition, a comprehensive evaluation of the seven grid connection technologies for large OWFs is proposed based on eight specific indicators. Finally, eight conclusions and six perspectives are outlined for future research in integrating large OWFs.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The issues of environmental pollution and insufficient fossil fuel energy are becoming increasingly severe. To mitigate environmental degradation and optimize energy structure [1, 2], renewable energy sources (RESs), such as solar energy and wind energy, have received widespread attention all over the world [3,4,5,6,7].

Wind energy had more deeper exploitation than solar energy because of its advantages of wide distribution and mature technologies [8,9,10,11]. Despite the vigorous development of onshore wind power, it is currently facing the challenges of noise produced by wind turbines (WTs) and the availability of land. Offshore wind farms (OWFs) [12] have received global interest because of the enormous untapped wind resources and better wind regime. Currently, OWFs are developing towards having large capacity and long-distance transmission, while grid connection of OWFs has brought new challenges to technology and economy. Therefore, it is necessary to explore proper power transmission technologies that can connect large OWFs to the onshore power grid over long distances [12,13,14]. Over the past 20 years, different transmission schemes for large OWF integration have been proposed and discussed, and the majority of the researches centers on the operational feasibility and economics of each transmission system [15,16,17,18].

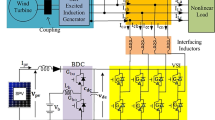

Thus far, three types of transmission technologies have been proposed for large OWF integration, i.e., high voltage alternating current (HVAC) transmission [16], high voltage direct current (HVDC) transmission [15], and low-frequency alternating current (LFAC) or fractional frequency alternating current (FFAC) transmission [18], as shown in Fig. 1. HVAC technology is a common and cost-efficient power transmission mode for large-scale new energy industries. Consequently, this transmission system is the first choice for most large OWFs [19, 20]. However, the power loss of the system has a strong correlation with the distance. The large reactive power loss on the cable is the biggest shortcoming of HVAC, and therefore its transmission distance is often limited. Since OWFs will tend to be built further offshore in the future, HVDC and LFAC may become the only solutions for ultra-long distance power transmission [18, 21]. There are five topologies based on HVDC systems, i.e., line commutated converter HVDC (LCC-HVDC) [22], voltage source converter HVDC (VSC-HVDC) [23], hybrid-HVDC [24], diode rectifier based HVDC (DR-HVDC) [25], and all direct current (ALL-DC) [26] transmission system. HVDC has the edge in terms of cost, efficiency, and applicability compared with HVAC, especially VSC-HVDC and ALL-DC systems that are prevalent in most OWFs. LFAC [18, 27] is developed from HVAC transmission technology and works at one-third of power frequency (such as 50/3 Hz or 60/3 Hz). This system minimizes offshore converter stations and enhances the transmission capacity of AC cables compared with HVAC. However, HVAC and HVDC have already been widely applied in OWF integration, while LFAC has only had engineering experience in railway electrification systems. LFAC transmission technology is still under development, though it very significant for improving reliability and reducing the complexity of future OWFs [27].

Until now, several reviews of grid connection technologies for OWF integration have been published, and their main contents and limitations are illustrated in Table 1.

To comprehensively introduce grid connection technologies for large OWFs, this work reviews seven power transmission technologies and the corresponding fault ride-through (FRT) techniques for integration of large OWFs. The performance of all transmission technologies is also evaluated. Finally, this work presents some perspectives for the future development of grid connection of large OWFs. The organization of this work is demonstrated in Fig. 2, and the main contributions and innovations of this work are listed as follows:

-

The existing grid connection technologies for large OWFs are reviewed, including HVAC, LFAC, and five HVDC topologies such as LCC-HVDC, VSC-HVDC, Hybrid-HVDC, DR-HVDC, and ALL-DC transmission system. To the best of authors' knowledge, there has been no such comprehensive review of the grid connection technologies for large OWFs.

-

The research of FRT mainly focuses on system stability, especially the control of voltage and frequency. This paper summarizes several novel FRT technologies for grid connection of large OWFs, and provides some references for researchers.

-

Economic analysis and transmission distances of all grid connection technologies must be considered for OWFs. Consequently, this paper comprehensively evaluates the seven grid connection technologies based on five specific indicators, and summarizes the application and performance of every scheme. The relationships of the transmission distances with the overall cost and active power for three integration technologies are analyzed in this work.

-

According to previous studies and the analysis in the paper, this work outlines eight conclusions and six perspectives for the development of future large OWFs, and points out that All-DC and LFAV transmission technologies have great significance for the cost-effective integration of future large OWFs.

2 Review screening methods

To collect the statistics of literature on OWF connection, this work uses three Scopus services (Elsevier, Google Scholar, and Web of Science) to investigate related references by searching keywords and phrases, such as large OWFs, HVDC, HVAC, LFAC, and transmission system. The process of literature selection and statistical results is demonstrated in Fig. 3.

3 Grid connection technology of large offshore wind farm

Compared with onshore wind farms, the construction, installation, and power transmission of OWFs are technically more complicated and expensive [14]. At present, there is no independent design method and standard for offshore WTs anywhere in the world [15]. There are two basic modes of grid connection of OWFs: AC transmission and DC transmission.

3.1 HVAC transmission system connection

3.1.1 Topology type and basic control strategy

The structure of OWFs based on HVAC is shown in Fig. 4 [16]. The voltage amplitude and frequency from the wind turbine generator (WTG) are variable. The varying frequency AC current of the WTG is converted into the AC current with the synchronous frequency of the power grid after being transformed by a converter. Then the power is transmitted to an onshore substation through a submarine cable after step-up transformers. Since the voltage level of the offshore array of OWFs is usually in the range of 30–36 kV [19] while the transmission voltage is in the range of 132 kV to 400 kV, the offshore step-up transformer plays an important role in the power transmission system.

HVAC transmission technology is a mature and cost-efficient system for power transmission of large-scale renewable energy. Consequently, this transmission system is the first choice for most large OWFs. However, the high capacitance of HVAC cables produces reactive current and results in high power loss. Thus, the transmission distance of HVAC is limited. The active power transmission capability of HVAC cable and the reactive power produced by the capacitive charging current are given as [21, 32]:

where PR is the maximum transmissible active power, \({Q}_{\mathrm{c}}\) is the reactive power, \({S}_{\mathrm{th}}\) is the maximum apparent power, C is the capacitance of the cable, l is the transmission distance, E is the rated voltage, and \(f\) is the frequency.

Figure 5 illustrates the relationship between the active power that can be transmitted by HVAC submarine cable at different frequencies and distances [33, 34].

3.1.2 Fault ride through technology

Various generator systems have been used in OWFs [35,36,37,38]:

-

(a)

Squirrel-cage induction generator (SCIG);

-

(b)

Doubly-fed induction generator (DFIG);

-

(c)

Permanent magnet synchronous generator (PMSG).

FRT technology of offshore wind power based on HVAC transmission system can be divided into low voltage ride-through (LVRT) and high voltage ride-through (HVRT) [39, 40]. At present, LVRT requirement is considered as the most stringent one. LVRT requirements of some countries are shown in Fig. 6 [41, 42], while LVRT requirements of the USA references to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). However, there is no relevant operational standard for HVRT of wind farms in China, while [43] proposes HVRT technical requirements for developed countries.

FRT technologies of onshore wind farms are used in OWFs [44]. References [45,46,47] summarize FRT strategies for different WT systems in onshore wind farms. There are two typical methods to realize FRT, i.e., improving the external devices and modifying the controller. FRT technologies and generator systems of offshore wind power based on HVAC transmission system are summarized and categorized in Table 2.

3.2 HVDC transmission system connection

A large number of studies have confirmed that HVAC subsea transmission scheme has distinctive limitations in transmission distance, power losses, and resonance problems. An HVDC transmission scheme is preferred for integrating OWFs over long distance, which can effectively overcome the problems of cable charging current and reactive power loss of AC cables [52]. A detailed analysis and assessment of HVDC transmission systems based on a global scale is presented in [53]. The development of HVDC transmission systems is mainly based on LCC and VSC, where LCC is also known as the current source converter (CSC) [22, 23]. Recently, some studies have suggested hybrid-HVDC [24] and DR-HVDC [25] based on LCC and VSC. In addition, to further reduce the cost of HVDC transmission systems, ALL-DC system [26] has been proposed for OWF integration.

3.2.1 Topology type and basic control strategy

-

1.

LCC-HVDC

LCC-HVDC using thyristors is the most widely applied technology for long distance and large capacity transmission on land [54,55,56]. However, the large volume of LCC converter stations adds difficulties to onshore installation, and it seems unrealistic to build LCC stations offshore. Therefore, LCC-HVDC transmission technology is only suitable for establishing an on-land LCC station [57].

Reference [58] illustrates the schematic representation of OWFs and LCC-HVDC link connection, as shown in Fig. 7. The operation of an LCC requires a commutation voltage, so it does not have black start capability and cannot supply power to a passive network. As there is no commutation voltage before the start-up of wind farms, an external device, such as a STATCOM, is required to provide a stable AC voltage for the converter [59]. The impedance models for wind turbine inverters, LCC-HVDC rectifier, and STATCOM can be found in [60].

Some novel control strategies of LCC-HVDC have been proposed in several papers. Reference [61] presents a system that comprises an LCC-HVDC and a STATCOM for connecting DFIG-based OWFs. A series tapping station based on a CSC for offshore wind power integration is introduced in [62], while [54] addresses the simulation of direct voltage and frequency control of OWFs with an LCC-HVDC connection. A scheme using a designed adaptive-network-based fuzzy inference system (ANFIS) damping controller at the inverter station of an HVDC link is proposed in [63]. It is noteworthy that the filter design is one of the most difficult areas in the development of LCC-HVDC. Reference [64] proposes to use WTs with fully rated converters to reduce HVDC rectifier filter requirement.

-

2.

VSC-HVDC

At present, VSC-HVDC technology is implemented in most large OWFs throughout the world. Using power electronic devices, such as the gate turn-off thyristor (GTO) and insulated-gate bipolar transistor (IGBT) that can be turned on and off, VSC-HVDC has the capability of black start and can interconnect passive networks. The advantages of VSC-HVDC transmission technology make it more suitable for the grid connection of OWFs than LCC-HVDC [12, 65]. Moreover, the application of VSC-HVDC facilitates the realization of multi-terminal grids and future global power interconnection.

-

(a)

Two-terminal VSC-HVDC

Figure 8 shows a typical two-terminal VSC-HVDC transmission system for integrating OWFs. The system is comprised of converters, transformers, phase reactors, AC filters, DC cables, circuit breakers, DC capacitors, and filters [12]. The converter stations in VSC-HVDC have a variety of configurations, among which two-level and three-level converters have been applied to small OWFs [29, 66].

With the development of power electronics technology, especially the widespread application of MMC in VSC-HVDC, the economy and efficiency of VSC-HVDC systems have been significantly increased [67, 68]. As shown in Fig. 9, MMC is different from the traditional two or three-level converters, and can reduce switching frequency and switching loss, and provide better power quality [69, 70]. References [71, 72] introduce the operation principle, mathematical model, and impedance model of an MMC-HVDC. The startup sequence of OWFs with MMC-HVDC grid connection can be found in [73].

Research on MMC-HVDC systems mainly focuses on MMC modulation method, control of submodule capacitor voltage, and AC/DC fault protection. MMC modulation methods can be divided into carrier pulse width modulation (PWM), multilevel voltage space vector modulation, and multilevel step wave modulation.

Reference [74] illustrates the impact of controller parameters on system stability. Some techniques of MMC-HVDC for OWFs integration are summarized in [12, 29], and recent related studies are listed in Table 3.

-

(b)

VSC-MTDC

At present, the typical two-terminal VSC-HVDC system has many worldwide applications, but the two-terminal system is no longer suitable for connecting the grid with multi-regional renewable energy [81]. OWFs are scattered in different areas because of environmental limitations. In addition, onshore converter stations are also distributed in different regions because of the geographical locations of the load centers. Consequently, MTDC can provide more economic and technological benefits than the typical two-terminal HVDC [82]. VSC is more appropriate for realizing MTDC transmission than LCC since the direction of power flow can be flexibly controlled by VSC-HVDC without changing the polarity of DC voltage [83]. The structure of an MTDC-VSC is shown in Fig. 10.

The topological structure of VCS-MTDC systems is directly related to the reliability and practicability of the control strategy. There are many different topologies of an MTDC system. They can be applied in the power transmission of large OWFs. References [84, 85] classify the topologies of MTDC systems into several types, mainly including point-to-point, general ring, star, star with central switching ring, wind farms ring, and substation ring topologies. In general, they can be divided into four types of structure: (a) radial; (b) ring; (c) lightly meshed; (d) densely meshed [86]. The selection of the appropriate MTDC topology depends on the system requirements for operation and robustness, as well as the geographical locations of the substations and OWFs [12].

Studies on MTDC mainly focus on system stability, network control stagey, AC/DC fault protection, while the control of converter station and DC voltage are crucial to the stability of VSC-MTDC systems. The control system of an MTDC network generally consists of an AC grid side s, wind farm side, and DC power flow control systems [85, 86]. Reference [87] discusses the modeling and control of VSC-MTDC systems and presents a link between power flow models and steady-state operating points. To enhance system stability, reference [88] proposes a two-level combined control scheme for VSC-MTDC integrated OWFs. However, system control and DC breakers are the most challenging tasks in MTDC transmission networks. A communication-less DC voltage cooperative control strategy for MTDC transmission systems is proposed in [89] to effectively maintain a stable DC link voltage.

MMC-based MTDC (MMC-MTDC) enables multiple power sources at multiple locations. As a flexible and efficient transmission mode, MMC-MTDC has broad application prospects in grid connection of OWFs and other renewable energy. China is in a leading position in this transmission technology. So far, there are only three MMC-MTDC projects in the world, i.e., Nan’ao three-terminal project, Zhoushan five-terminal project, and Zhang-Bei ± 500 kV four-terminal demonstration project [90]. There are usually three control levels for an MMC-MTDC system, i.e., system, converter station, and valve levels. Most MMC-MTDC control systems use double closed-loop PI control strategies. In recent years, the studies of MMC-MTDC mainly focus on the improvement of traditional control methods and the protection of DC line faults [91,92,93,94]. Although MMC-MTDC technology has not yet been applied in existing OWFs, it has great potential for grid connection of large OWFs.

From these studies, the main technologies of system stability and network control strategy based on VSC-MTDC are summarized in Table 4.

-

3.

Hybrid-HVDC

As shown in Fig. 11, to reduce HVDC converter loss, capital cost, and footprint of offshore station and consider the relative benefits of LCC and VSC systems, a hybrid HVDC system is proposed, one which uses a VSC at the offshore terminal and an LCC at the onshore terminal [108, 109]. The other topology with an LCC at offshore and a VSC at the onshore, is not suitable for OWF integration because LCC station is too large for an offshore platform [110]. A novel hybrid HVDC transmission system that consists of a PWM-CSC and an LCC is proposed in [111, 112], in which PWM-CSC replaces VSC because it has similar advantages as VSC for integration of OWFs.

References [109, 113, 115] conduct critical studies on the feasibility of using hybrid HVDC technology to integrate OWFs from the aspects of cost, loss, and FRT, and propose some control strategies for the entire system. However, hybrid HVDC systems have a serious limitation, as when an AC fault occurs at LCC inverter, the fault can be converted into a DC fault and potentially destroy the entire hybrid system [108, 110]. Commutation failure of LCC has always been the most challenging issue in hybrid HVDC systems [55, 115].

Although hybrid HVDC systems have the shortcoming of commutation failure, the possibility of commutation failures can be reduced by devising appropriate control strategies. Hybrid HVDC topology that combined LCC and MMC is validated as an effective solution to alleviate commutation failures. For example, references [110, 115] study the commutation failure in hybrid HVDC systems and evaluate the characteristics of different types of MMC (half-bridge and full-bridge) in reducing commutation failure. Furthermore, considering the limitation of MMC capacity, references [116, 117] propose an improved control strategy that can address the transient stability problem.

Lastly, as LCC absorbs reactive power for commutation, AC voltage of hybrid HVDC system will fluctuate because of wind power variation. Reference [112] proposes a control method for DC current and voltage droop, one which suppresses AC voltage fluctuation at LCC grid side. The topologies and characteristics of hybrid HVDC are comprehensively summarized in Table 5.

-

4.

DR-HVDC

To reduce the cost associated with offshore wind power integration, DR-HVDC has recently received considerable attention. The topology of OWFs collected by DR is shown in Fig. 12. This is beneficial for reducing transmission loss and total cost by replacing VSC offshore station by DR [118,119,120]. Although DR-HVDC is economical, it brings many challenges since the control capabilities of an offshore VSC station is lost. An important reason why the technology has not been widely used for HVDC transmission is the lack of control capability of DR [121, 122].

So far, due to the superior controllability of MMC and the compactness of DR, using auxiliary devices that consist of MMC and DR is the most popular solution to address the shortcomings of DR-HVDC. Some novel topologies of DR-HVDC are listed in Table 6.

Offshore AC grid control, start-up, communication-less control, and synchronization are the main challenges for DR-HVDC. Reference [126] reviews three control strategies for AC grid formation and operation of DR-HVDC-based OWFs and points out that any solution must address these problems.

-

5.

ALL-DC Connection

Offshore All-DC wind farms are characterized by DC collection and DC transmission. These can eliminate the power frequency transformer and multiple power converters, and have advantages in power density, cost, and efficiency. According to the connection mode of WTs, the proposed technology for All-DC OWFs can be divided into two types, i.e., series and parallel schemes [127].

-

(a)

Series-connection WTs scheme

For series-connection WTs-based OWFs, as shown in Fig. 13, the series scheme can directly step up DC voltage to HVDC transmission level by series connecting DC wind turbines (DCWTs). This topology eliminates DC-DC converter stations and offshore platforms, thereby the capital cost can be significantly reduced.

However, insulation coordination and strong power-voltage coupling among the series-connected WTs are the main technical challenges. To solve these two problems and especially the system coupling, references [128, 129] propose an approach which installs MMC in the main network at the receiving-end, while [130] proposes a multi-functional DC collector to achieve energy collection and cascade boost, in which not only the coupling among WTs is weakened, but also the cost and size of the system are both reduced. Table 7 summarizes the challenges and solutions for series-connection WTs in recent years.

-

(b)

Parallel-connection WTs scheme

The parallel-connection WTs scheme is shown in Fig. 14. This topology has no strong current coupling among wind power converters, and the control of OWFs is not complex. Converters are directly connected to the medium-voltage direct current (MVDC) grid, so a step-up station is required. Since the output voltage of wind power generators is low, the design of high voltage step-up DC-DC converter stations of parallel-connection WTs becomes a core issue [127].

From the perspective of power collection, there are three types of offshore step-up substation including AC collection, DC series collection, and DC parallel collection, as shown in Fig. 15. Table 8 summarizes the characteristics of various topologies [136,137,138]. Under traditional control strategy, DC wind farms act as a current source for the power grid, with the characteristics of small inertia, no damping, and no response to the frequency of the power grid.

3.2.2 Fault ride-through technology

An HVDC transmission system for connecting large OWFs has different fault responses from those of conventional AC systems [139]. As mentioned above, commutation failure, filter design, and reactive power flow are the common problems for LCC-HVDC. In addition, because of the long distance between the generator-side and grid-side converters, the grid voltage dip cannot be accurately identified by the generator-side controller during faults [140]. The control of frequency, voltage and DC-link current is critical for FRT.

There are two methods used for FRT of OWFs based on a VSC-HVDC network. One is the chopper resistor method, which limits DC-link voltage by dissipating the imbalanced power as heat. Reference [141] proposes a flywheel energy storage system (FESS), in which the imbalance power during fault is absorbed by FESS instead of being dissipated in the form of resistive losses. However, the high investment cost is the major drawback of the chopper resistor method. The other is to reduce the output of the wind farm by directly controlling WTs or adjusting the voltage and frequency of the wind farm. In addition, some studies [142,143,144] present DC protection strategies that can eliminate DC short circuit faults by using mixed cell modular multi-level converters (MC-MMCs).

Hybrid HVDC and DR-HVDC are developed based on LCC and VSC so that FRT technology is closely related to LCC and VSC. The methods of realizing FRT for the first four HVDC topologies for OWFs integration are listed in Table 9.

For an ALL-DC system, DC cable failure may affect the operation of ALL-DC OWF system. There are no differences between the onshore converter station of ALL-DC OWFs system and VSC-HVDC system. Thus, most DC fault diagnosis and protection methods are also applicable to ALL-DC OWF system [142,143,144].

However, WT type is the biggest difference between ALL-DC system and the other four HVDC topologies. The operation of ALL-DC OWFs results in significant WT output voltage variation. Thus, different technologies are needed to realize ALL-DC system FRT, especially DCWT protection [164]. Reference [165] analyzed the characteristics of a transmission line fault in a DC wind farm and developed a fault protection method for a wind farm DC network, while [166] studies the redundancy of the system during DC line failures and proposes a DC FRT strategy. The transient characteristics during WT and transmission line faults in a series-connection OWF system are discussed in [167]. Table 10 provides a comprehensive and detailed summary of FRT technology of ALL-DC OWF system.

3.3 LFAC transmission system connection

Recently, studies on reducing the complexity and cost of OWFs, and increasing reliability have received interest from both industry and academia. For cost-effective connection of large OWFs, an LFAC transmission scheme is proposed. Although LFAC only has engineering practice in railway electrification systems, it can be an alternative for HVAC transmission schemes. As for OWFs with a transmission distance of 80–180 km, LFAC may be more cost-effective than either HVAC or HVDC systems [30, 31].

3.3.1 Topology type and basic control strategy

A general layout of LFAC transmission system is shown in Fig. 16. LFAC is an adaptation from HVAC technology and operates at one-third of the nominal frequency. This scheme uses AC cables working at low frequency to transmit power from OWFs to the onshore back-to-back (BTB) frequency converter, which converts back from low frequency to the grid frequency [173]. Compared with HVAC, the power transfer capacity and distance of LFAC system are increased under the lower frequency environment. Another advantage is that LFAC system does not need an offshore converter station, so the complexity and cost are reduced considerably compared to HVDC [18, 21, 174].

There are different converter types applied in LFAC system, including cycloconverter, matrix converter, and BTB-VSC. The topologies of the cycloconverter and matrix converter are shown in Figs. 17 and 18, respectively. Reference [175] proposes an approach to use a modular multilevel matrix converter (M3C) working as a frequency converter for OWFs. Some studies have pointed out that an LFAC system with an onshore BTB-VSC converter produces more power losses than the cycloconverter. However, in terms of the filtering requirements, reliability of grid integration and system cost, BTB-VSC is a better choice for LFAC transmission systems [176].

For a multi-terminal offshore grid, the multi-terminal network can be larger because LFAC can increase AC transmission range for connecting OWFs. Compared with multi-terminal HVDC, the meshed AC connection of LFAC system links can be easily achieved by the existing low-frequency AC circuit breaker and expertise. Also, the design of a low-frequency circuit breaker is easier than of a DC circuit breaker.

3.3.2 Fault ride-through technology

As a full power electronic grid, harmonic stability and frequency support provide significant challenges for the fault and protection technologies of offshore LFAC systems. Reference [177] summarizes the limitations of oscillation and short circuit current in LFAC system when the speed of WTs is constant, while [178] presents a method of analyzing harmonic stability. This shows that the control parameters, such as current and voltage control bandwidths, can influence harmonic stability. An approach of enhancing the frequency support capability of generators is developed in [179], one which can effectively protect the transformers when the frequency drops.

LFAC transmission technology has significant potential for OWF connection. Most papers focus on the simulation of frequency converter and the economy of the system. Some FRT technologies applied in HVAC may be suitable for LFAC, and FRT technology of offshore LFAC transmission system is at the development stage.

4 Economic analysis of grid connection technologies

The economic analysis of OWF integration technologies (HVAC, HVDC, and LFAC) has long been a research hotspot. The economic evaluation mainly concentrates on cost and transmissive power, and the overall cost of a large OWF connection system often includes the terminal cost and route cost. The terminal cost of HVAC systems is cheaper than that of HVDC systems which have expensive power converter stations. However, compared with HVDC system, the route cost of HVAC systems rises much more sharply with distance [19]. Thus, HVAC is applicable for short distance offshore power transmission, while HVDC is more suitable for OWF connection when the transmission distance exceeds the threshold. Research in [180] shows the intersection of HVAC and HVDC costs is in the region of 80 km for subsea cable transmission systems.

Figure 19 shows the relationship between the overall cost and transmission distance for different OWF connection technologies. Reference [18] evaluates the key technologies and costs of transmission systems for large OWF connection applications and summarizes the economic ranges of different transmission systems based on distance and power. The economic ranges of HVAC, HVDC, and LFAC are shown in Fig. 20.

5 Summary and discussion

HVAC is a desirable choice for OWFs with an offshore distance less than 60 km. The reactive current from AC cables is the major limitation of HVAC transmission technology. In contrast, HVDC has no capacitance effect, so it is regarded as the most economical solution for long distance power transmission. In addition, VSC-HVDC has the benefits of distinct control and design structure, and is deemed as the technology leader for OWF integration at distances of more than 100 km. However, the building of offshore stations is a huge challenge when considering overall cost and reliability. LVAC transmission technology is a novel approach for OWF connections. Although there is no practical LVAC experience with OWFs, many studies have shown the significance of LVAC for future OWF integration. In summary, the classification and performance of large OWF grid connection technologies are elaborated in Table 11, and Table 12 introduces some engineering examples of the three integration technologies.

Figure 21 shows the evaluation of the characteristics of existing OWF integration technologies. The evaluation includes five specific indicators, i.e., economic, complexity, reliability, feasibility, and superiority [18, 21, 30, 31, 152]. The evaluation criteria of each integration technology are given as follows:

-

(a)

Economic evaluation mainly includes construction cost, transmission losses, and transmission capacity, while each of the following elements will contribute to the additional economic level: (i) less reactive power loss of cable; (ii) no offshore converter station; (iii) no expensive power electronics such as IGBT; (iv) no HVDC circuit breaker; (v) bulk capacity and long-distance transmission.

-

(b)

Complexity is mainly evaluated by structure of transmission line, type of WTs, and complex power electronic equipment. The following elements influence the complexity level: (i) application of MMC; (ii) number of AC-DC conversion steps; (iii) construction of offshore converter station; (iv) additional reactive power compensation device.

-

(c)

Reliability is mainly evaluated by the possibility of faults, which are divided into five levels: (i) higher than 30% (very low); (ii) 15%-30% (low); (iii) 10%-15% (medium); (iv) 5%-10% (high); (v) lower than 5% (very high). LCC-HVDC has a higher possibility of commutation failure so its reliability is the lowest in all integration technologies.

-

(d)

Feasibility mainly depends on reliability and cost, and is influenced by the following elements: (i) construction of offshore converter station; (ii) offshore wind plant down time; (iii) the number and size of OWF physical assets.

-

(e)

Superiority is mainly evaluated by each technology’s proposed time and contribution on the economic and system simplification, while the following elements contribute to superiority level: (i) proposed after 2000; (ii) reduce the system complexity; (iii) fewer AC-DC converter stations; (iv) reduce the reactive power loss of cable; (iv) long-distance transmission.

6 Conclusions and perspectives

This work comprehensively summarizes three types of grid connection technologies of large OWF integration, which contain seven transmission technologies: HVAC, LCC-HVDC, VSC-HVDC, Hybrid-HVDC, DR-HVDC, ALL-DC, and LFAC. FRT technologies for each grid connection scheme of large OWFs are also thoroughly investigated, together with several control strategies of overvoltage and SFD. Furthermore, a reasonable and considered evaluation is proposed to undertake a detailed and comprehensive comparison of different transmission systems for large OWF integration, one which provides practical instructions and guidelines for researchers and engineers working in the field. The main conclusions are:

-

Conventional HVAC transmission technology has high reliability and mature application experience, and is therefore considered as the first choice for most large OWFs. However, with the construction of offshore wind farms being further away from the onshore connection point, the transmission distance of HVAC system is limited by the capacitive charging effect of the cables. Thus, HVAC is suitable for OWFs at a distance less than 60 km;

-

Though HVDC transmission technology does not have reactive power loss on cables, the cost of offshore and onshore converter stations is greatly increased. Therefore, an HVDC scheme is more appropriate for large OWFs over long transmission distances;

-

Although LCC-HVDC has been extensively applied in onshore power networks and wind farms, it is difficult to build LCC stations offshore. Thus, LCC transmission technology must be coordinated with other technologies to provide a more cost-efficient scheme for large OWF integration;

-

Because of the benefits of distinct control and design, VSC-HVDC has become the technology leader for OWF integration at distances of more than 100 km. The development of MMC technology greatly reduces the capital investment and complexity of VSC-HVDC systems;

-

Hybrid-HVDC combines the benefits of VSC and LCC, and can reduce converter loss, capital cost, and footprint of the offshore station. However, the biggest challenge of LCC is commutation failure, which may cause the failure of Hybrid-HVDC systems. The possibility of LCC commutation failure can be significantly decreased by using MMC, and the system with an MMC station offshore and LCC station onshore is critical to the economic operation of large OWFs.

-

DR can replace VSC offshore station and reduce transmission loss and total cost, but the uncontrollability of DR brings challenges to the stability of DR-HVDC system. However, MMC technology has superior controllability, and MMC as an auxiliary device of DR can effectively solve this problem;

-

ALL-DC transmission systems need specially designed DCWTs. As a novel transmission technology, such configuration eliminates the requirement of offshore power frequency transformers and power converters. Thus, ALL-DC possesses promising potential for the development of OWF integration;

-

LFAC can overcome the disadvantages of HVAC, and further reduce the complexity and cost of the system. At the same time, the reliability of the operation of OWFs is also being improved. Although LFAC technology only has engineering practice in rail track electrification systems, it can be further explored for replacing HVAC or HVDC for integrating large OWFs.

In general, various integration technologies have their own respective performance and applications. The motivation of these transmission technologies is to increase the efficiency of power transmission and minimize the cost and complexity of the system. This work has discussed such systems for large OWF integration, aiming to greatly improve the development of offshore wind power and optimize the energy structure.

Future studies of grid connection technologies for large OWFs integration will mainly focus on the following aspects:

-

The development of offshore wind power provides a promising scheme to alleviate the issue of climate change and energy supply, while OWFs have fewer visual and noise problems than onshore wind farms. Nevertheless, the marine ecosystem is influenced by the construction of OWFs, while the perch of some halobios may also be disturbed. Therefore, the impact of OWFs on the marine ecosystem must be studied in detail, and the grounding electrode should be reduced when connecting offshore converter stations to reduce the impact of high current return on the ecosystem. To this end, the construction, operation, and maintenance of OWFs should minimize the negative impact on the ocean system;

-

OWFs are developing towards large capacity with long distance power transmission, and thus, the transmission system for large OWF integration must focus on reducing system complexity and enhancing the overall feasibility, especially in the design of offshore WTs. The quality of components still needs to be improved and the installation time reduced. Moreover, future OWFs will feature higher towers, larger rotors, and more advanced electrical technology. The main operation and characteristics of future OWFs are defined by six core areas, that is, quantity of wind farms, number of WTs, installed capacity, water depth, turbine height, and transmission distance;

-

There is a prominent trend that more power electronic devices, such as MMC, will be introduced in the transmission technology of OWFs, but the system stability of AC grid may also be influenced at the same time. Thus, the operational performance of voltage and frequency should be investigated. In particular, the issues of frequency drop, oscillation, and active frequency support are the main challenges for the normal operation of OWF systems;

-

ALL-DC and LVAC transmission technologies have been proposed in recent years. These, in theory, can improve the operation economy, but they lack engineering practice. Moreover, the economic startup of ALL-DC systems and DR-HVDC systems should also be investigated. In general, it is imperative to further explore the implementation feasibility of new technologies for large OWF integration:

-

Fault response and protection of OWFs are discussed in many studies. With the application of new transmission technologies on OWF integration, FRT technologies still need more in-depth study and investigation. Currently, artificial intelligence shows the greatest potential for promoting the development of future FRT technologies for OWFs;

-

Cost-effective distances and economic evaluation of the seven grid connection technologies for large OWFs differ among different studies. Therefore, the applications and assessments of all technologies should be more precise and comprehensive.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AC:

-

Alternating current

- ANFIS:

-

Adaptive-network-based fuzzy inference system

- ALL-DC:

-

All direct current

- BTB:

-

Back-to-back

- CSC:

-

Current source converter

- CSI:

-

Current source inverter

- DC:

-

Direct current

- DR:

-

Diode rectifier

- DFIG:

-

Doubly fed induction generator

- DCMC:

-

Direct current matching control

- DCSVC:

-

Double closed-loop space vector control

- FRT:

-

Fault ride through

- FFAC:

-

Fractional frequency alternating current

- FCG:

-

Full converter generator

- FESS:

-

Flywheel energy storage system

- FACTS:

-

Flexible alternating current transmission systems

- FB-MMC:

-

Full bridge modular multi-level converter

- FERC:

-

Federal energy regulatory commission

- GTO:

-

Gate turn-off thyristor

- HVAC:

-

High voltage alternating current

- HVDC:

-

High voltage direct current

- HVRT:

-

High voltage ride through

- HB-MMC:

-

Half-bridge modular multi-level converter

- IGBT:

-

Insulated-gate bipolar transistor

- LCC:

-

Line commutated converter

- LFAC:

-

Low-frequency alternating current

- LVRT:

-

Low voltage ride through

- MVDC:

-

Medium voltage direct current

- MMC:

-

Modular multi-level converter

- MC-MMC:

-

Mixed cells modular multi-level converter

- MERS:

-

Magnetic energy recovery switch

- MTDC:

-

Multi-terminal high voltage direct current

- OWF:

-

Offshore wind farm

- PWM:

-

Pulse width modulation

- PSVD:

-

Positive-sequence-voltage-dependent

- PMSG:

-

Permanent magnet synchronous generator

- PONC:

-

Perturbation observer-based nonlinear control

- PM-SM:

-

Parallel multiple submodule

- PI:

-

Proportion-integral

- PCC:

-

Point of common coupling

- RESs:

-

Renewable energy sources

- RSC:

-

Rotor side converter

- SFD:

-

Second frequency drop

- SCIG:

-

Squirrel-cage induction generator

- STATCOM:

-

Static synchronous compensator

- SVC:

-

Static var compensator

- VDCOL:

-

Voltage-dependent current order limiter

- VSC:

-

Voltage source converter

- WTG:

-

Wind turbine generator

- WT:

-

Wind turbine

References

Fernández, G. A., Gómez, L. G., et al. (2020). Power systems with high renewable energy sources: A review of inertia and frequency control strategies over time. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 115, 1–12.

Murty, V. V. S. N., & Kumar, A. (2020). Multi-objective energy management in microgrids with hybrid energy sources and battery energy storage systems. Protection and Control of Modern Power Systems, 5, 1–20.

Olusola, J. O. (2020). The legal sustainability of energy substitution in Nigeria’s electric power sector: Renewable energy as alternating. Protection and Control of Modern Power Systems, 5(4), 358–369.

Yang, B., Wang, J. B., Zhang, X. S., Yu, T., Yao, W., Shu, H. C., Zeng, F., & Sun, L. M. (2020). Comprehensive overview of meta-heuristic algorithm applications on PV cell parameter identification. Energy Conversion and Management, 208, 1–22.

Yang, B., Yu, T., Shu, H. C., Zhang, Y. M., et al. (2018). Passivity-based sliding-mode control design for optimal power extraction of a PMSG based variable speed wind turbine. Renewable Energy, 119, 577–589.

Yang, B., Yu, T., Shu, H. C., et al. (2018). Robust sliding-mode control of wind energy conversion systems for optimal power extraction via nonlinear perturbation observers. Applied Energy, 210, 711–723.

Yang, B., Zhong, L. E., Yu, T., et al. (2019). Novel bio-inspired memetic slap swarm algorithm and application to MPPT for PV systems considering partial shading condition. Journal of Cleaner Production, 215, 1203–1222.

Liu, J., Wen, J. Y., Yao, W., & Long, Y. (2016). Solution to short-term frequency response of wind farms by using energy storage systems. IET Renewable Power Generation, 10(5), 669–678.

Yang, B., Jiang, L., Wang, L., Yao, W., & Wu, Q. H. (2016). Nonlinear maximum power point tracking control and model analysis of DFIG based wind turbine. International Journal of Electrical Power and Energy Systems, 74, 429–436.

Yang, B., Yu, T., Zhang, X. S., Li, H. F., et al. (2019). Dynamic leader based collective intelligence for maximum power point tracking of PV systems affected by partial shading condition. Energy Conversion and Management, 179, 286–303.

Guchhait, P. K., & Banerjee, A. (2020). Stability enhancement of wind energy integrated hybrid system with the help of static synchronous compensator and symbiosis organisms search algorithm. Protection and Control of Modern Power Systems, 5(1), 1–13.

Korompili, A., & Zhao, A. (2016). Review of VSC HVDC connection for offshore wind power integration. Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews, 59, 1405–1414.

Wang, Q., Yao, W., Fang, J. K., et al. (2020). Dynamic modeling and small signal stability analysis of distributed photovoltaic grid-connected system with large scale of panel level DC optimizers. Applied Energy, 259, 1–21.

Zhang, Z. (2012). Study on power transmission technology for offshore wind farm. Jiangsu Electrical Apparatus, 7, 1–4.

Zhang, H., Dou, J., & Wei, S. (2013). Study on intelligent grid-connected controller for offshore distributed wind power system. Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering, 216, 159–166.

Reed, G. F., Hassan, H. A., Kory, M. J. et al. (2013). Comparison of HVAC and HVDC solutions for offshore wind farms with a procedure for system economic evaluation. In 2013 IEEE Energy tech. May 21–23, 2013, Cleveland, USA (pp. 1–7).

Yao, W., Jiang, L., Wen, J. Y., Wu, Q. H., & Cheng, S. J. (2015). Wide-area damping controller for power system inter-area oscillations: A networked predictive control approach. IEEE Transactions on Control Systems Technology, 23(1), 27–36.

Meng, Y., Yan, S., Wu, K., et al. (2021). Comparative economic analysis of low frequency AC transmission system for the integration of large offshore wind farms. Renewable Energy, 179, 1955–1968.

Negra, N. B., Todorovic, J., & Ackermann, T. (2006). Loss evaluation of HVAC and HVDC transmission solutions for large offshore wind farms. Electric Power Systems Research, 76, 916–927.

Dakic, J., Cheah, M., & Gomis, B. O. (2020). HVAC transmission system for offshore wind power plants including mid-cable reactive power compensation: Optimal design and comparison to VSC-HVDC transmission. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery, 36, 2814–2824.

Xiang, X., Merlin, M., & Green, T. C. (2016). Cost analysis and comparison of HVAC, LFAC and HVDC for offshore wind power connection. In 2016 IET international conference on AC and DC power transmission. May 28–29, 2016, Beijing, China (pp. 1–6).

Zhou, H. Y., Yao, W., Ai, X., et al. (2022). Coordinated power control of electrochemical energy storage for mitigating subsequent commutation failures of HVDC. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems, 134, 1–14.

Sun, K., Yao, W., Fang, J. K., Ai, X. M., Wen, J. Y., & Cheng, S. J. (2020). Impedance modeling and stability analysis of grid-connected DFIG-based wind farm with a VSC-HVDC. IEEE Journal of Emerging and Selected Topics in Power Electronics, 8(2), 1375–1390.

Lin, X., Guo, Q., Guo, H. et al. (2019). Simulation modeling and ac system fault control strategy for the multi-terminal hybrid HVDC system based on RTDS. In 2019 IEEE sustainable power and energy conference. November 21–23, 2019, Beijing, China (pp. 337–341).

Nami, A., Rodriguez, A. J., Arnaltes, S., et al. (2021). Control of the parallel operation of DR-HVDC and VSC-HVDC for offshore wind power transmission. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRD.2021.3095529

Holtsmark, N., Bahirat, H. J., et al. (2013). An All-DC offshore wind farm with series-connected turbines: An alternating to the classical parallel AC model. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, 60(6), 2420–2428.

Dakic, J., Cheah, M. M., et al. (2021). Low frequency AC transmission systems for offshore wind power plants: Design, optimization and comparison to high voltage AC and high voltage DC. International Journal of Electrical Power and Energy Systems, 133, 1–12.

Jie, W. A., Wang, Z. X., Lie, X. B., et al. (2014). Key technologies of VSC-HVDC and its application on offshore wind farm in China. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 36, 247–255.

Zhang, Y., Ravishankar, J., Fletcher, J., et al. (2016). Review of modular multilevel converter based multi-terminal HVDC systems for offshore wind power transmission. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 61, 572–586.

Ruddy, J., Meere, R., et al. (2016). Low frequency AC transmission for offshore wind power: A review. Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews, 56, 75–86.

Chaithanya, S., Reddy, V., & Kiranmayi, R. (2017). A narrative review on offshore wind power transmission using low frequency AC system. In 2017 international conference on smart technologies for smart nation. August 17–19, 2017, Bengaluru, India (pp. 52–58).

Kling, W. L., Hendriks, R. L., & Boon, J. (2008). Advanced transmission solutions for offshore wind farms. In: 2008 IEEE Power and Energy Society General Meeting-Conversion and Delivery of Electrical Energy. 20–24 July 2008, Pittsburgh, USA (pp. 1–6).

Mau, C. N., Ru, D. K., & Orths, A. (2012). Grid connection of offshore wind farm based DFIG with low frequency AC transmission system. In 2012 IEEE power and energy society general meeting. July 22–26, 2012, San Diego, USA (pp. 1–7).

Antunes, T. A., Santos, P. J., & Pires, A. J. (2017). HVAC transmission restrictions in large scale offshore wind farm applications. In 2017 IEEE international conference on compatibility, power electronics and power engineering. April 4–6, 2017, Cadiz, Spain (pp. 46–52).

Tummala, A. S. (2020). A robust composite wide area control of a DFIG wind energy system for damping inter-area oscillations. Protection and Control of Modern Power Systems, 5, 1–10.

Dhiman, H. S., & Deshpande, A. S. (2016). Fault ride-through capability of induction generator as offshore wind farm. In 2016 international conference on electrical, electronics, and optimization techniques. March 3–5, 2016, Chennai, India (pp. 961–965).

Yang, B., Zhang, X. S., Yu, T., et al. (2017). Grouped grey wolf optimizer for maximum power point tracking of doubly-fed induction generator based wind turbine. Energy Conversion and Management, 133, 427–443.

Chen, J., Yao, W., Zhang, C. K., Ren, Y., & Jiang, L. (2019). Design of robust MPPT controller for grid-connected PMSG-based wind turbine via perturbation observation based nonlinear adaptive control. Renewable Energy, 134, 478–495.

Tian, X., Li, Y., Guo, M., Ye, R., Huang, R., & Zhang, M. (2018). Active power and reactive power FRT coordinated control strategy of offshore wind farms connected to power grid with AC cables. In 2018 international conference on power system technology. November 6–8, 2018, Guangzhou, China (pp. 1249–1255).

Nadour, M., Essadki, A., et al. (2020). Improving low-voltage ride-through capability of a multimegawatt DFIG based wind turbine under grid faults. Protection and Control of Modern Power Systems, 5(4), 370–382.

Ibrahim, R. A., Hamad, M. S., Dessouky, Y. G., & Williams, B. W. (2012). A review on recent low voltage ride-through solutions for PMSG wind turbine. In 2012 international symposium on power electronics power electronics, electrical drives, automation and motion. August 13, 2012, Sorrento, Italy (pp. 265–270).

Yang, Y., Blaabjerg, F., & Wang, H. (2014). Low-voltage ride-through of single-phase transformer less photovoltaic inverters. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications, 50, 1942–1952.

Zhang, H., Chen, Y., & Zhan, C. (2015). Overview of high voltage ride through for doubly fed induction generators. Heilongjiang Electric Power, 37, 184–188.

Yuan, X., Yang. J., & Liu, H. (2018). FRT improvement strategy for offshore wind farm considering operation state. In: 2018 Youth academic annual conference of Chinese association of automation. 18–20 May 2018, Nanjing, China (pp. 421–426).

Nguyen, D. H., & Negnevitsky, M. (2010). A review of fault ride through strategies for different wind turbine systems. In 2010 Australasian universities power engineering conference, December 5–8, 2010. Christchurch, New Zealand (pp. 1–5).

Nasiri, M., Milimonfared, J., & Fathi, S. H. (2015). A review of low-voltage ride-through enhancement methods for permanent magnet synchronous generator based wind turbines. Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews, 47, 399–415.

Justo, J. J., Mwasilu, F., & Jung, J. W. (2015). Doubly-fed induction generator based wind turbines: A comprehensive review of fault ride-through strategies. Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews, 45, 447–467.

Liu, H., & Chen, Z. (2012). Fault ride-through and grid support of permanent magnet synchronous generator-based wind farms with HVAC and VSC-HVDC transmission systems. In 2012 IEEE international energy conference and exhibition. September 9–12, 2012, Florence, Italy (pp. 769–773).

Hussein, A. Z., Saad, N. H., & Mekamer, S. F. (2018). Reactive power and voltage control of offshore wind parks based PI controller tuning for STATCOM via genetic algorithm. In 2018 28th international middle east power systems conference. December 18–20, 2018, Cairo, Egypt (pp. 558–563).

Guo, H., Rudion, K., & Styczynski, Z. A. (2011). Integration of large offshore wind farms into the power system. In 2011 EPU-CRIS international conference on science and technology. November 16, 2011, Hanoi, Vietnam (pp. 1–6).

Peñalba, M. A., Bellmunt, O. G., & Martins, M. (2014). Coordinated control for an offshore wind power plant to provide fault ride through capability. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy, 5, 1253–1261.

Perveen, R., Kishor, N., & Mohanty, S. R. (2014). Offshore wind farm development: Present status and challenges. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 29, 780–792.

Alassi, A., Banales, S., Ellabban, O., et al. (2019). HVDC transmission: Technology review, market trends and future outlook. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 112, 530–554.

Chen, H. F., Liu, L., & Dong, Y. (2014). Review on integration program of large-scale offshore wind farm. Jiangsu Electrical Engineering, 33, 81–84.

Zhou, H. Y., Yao, W., Ai, X. M., Li, D. H., Wen, J. Y., & Li, C. H. (2022). Comprehensive review of commutation failure in HVDC transmission systems. Electric Power Systems Research, 205, 107768.

Liu, Z., Gao, H., et al. (2020). A fast boundary protection for an AC transmission line connected to an LCC HVDC inverter station. Protection and Control of Modern Power Systems, 5(4), 308–319.

Sun, S., Xiang, W., et al. (2017). Control and operation of a hybrid HVDC integrating wind farm based on SB-MMC and LCC. Journal of Engineering, 13, 816–821.

Rodriguez, A. J., Arnaltes, S., & Cardiel, M. A. (2017). Direct voltage and frequency control of an offshore wind farm connected through LCC-HVDC link. In 2017 European conference on power electronics and applications. September 11–14, 2017, Warsaw, Poland (pp. 1–10).

Anas, B., Jamal, B., et al. (2020). Comparative study of semiconductor power losses between CSI-based STATCOM and VSI-based STATCOM, both used for unbalance compensation. Protection and Control of Modern Power Systems, 5(1), 56–69.

Liu, H., & Sun, J. (2013). Small-signal stability analysis of offshore wind farms with LCC HVDC. In 2013 IEEE grenoble conference. June 16–20, 2013, Grenoble, France (pp. 1–8).

Foster, S., Xu, L., & Fox, B. (2008). Control of an LCC HVDC system for connecting large offshore wind farms with special consideration of grid fault. In 2008 IEEE power and energy society general meeting-conversion and delivery of electrical energy in the 21st century. July 20–24, 2008, Pittsburgh, USA (pp. 1–8).

Sau, B. J., Egea, A. A., & Prieto, A. E. (2015). Current source converter series tapping of an LCC-HVDC transmission system for integration of offshore wind power plants. In 2015 IET international conference on AC and DC power transmission. February 10–12, 2015, Birmingham (pp. 1–7).

Wang, L., & Thi, N. (2013). Stability enhancement of a PMSG-based offshore wind farm fed to a multi-machine system through an LCC-HVDC link. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems, 28, 3327–3334.

Blasco, G. R., Aparicio, N., Ano, V. S., & Bernal, P. S. (2012). LCC-HVDC connection of offshore wind farms with reduced filter banks. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, 60, 2372–2380.

Shen, Y., Yao, W., Wen, J. Y., He, H. B., & Jiang, L. (2019). Resilient wide-area damping control using GrHDP to tolerate communication failures. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, 10(3), 2547–2557.

Mao, Z. W., Xu, X. L., Jia, L., et al. (2018). Simulation research of offshore wind farm VSC-HVDC three-level converters for grid integration-science direct. Procedia Computer Science, 130, 1146–1151.

Song, G. B., Hou, J. J., & Chen, Z. H. (2020). Pilot protection of hybrid MMC DC grid based on active detection. Protection and Control of Modern Power Systems, 5(1), 82–96.

Beddard, A., & Barnes, M. (2015). Modelling of MMC-HVDC systems-an overview. Energy Procedia, 80, 201–212.

Dionisio, R. A., Fernando, M. R. B., Santiago, D. P. B., et al. (2017). Assessment of a nonlinear current control technique applied to MMC-HVDC during grid disturbances. Renewable Energy, 101, 945–963.

Tang, W., Shi, M., Li, Z., & Yu, N. (2019). Loss comparison study of MMC-HVDC and All-DC offshore wind farm. In 2019 IEEE innovative smart grid technologies-Asia. May 21–24, 2019, Chengdu, China (pp. 171–175).

Zhang, L., An, W., Zhang, D., Chen, G., Xi, L., & Ji, X. (2014). Modular multi-level converter designed for DC-based offshore wind farm. In 2014 international power electronics and application conference and exposition, November 5–8, 2014, Shanghai, China (pp. 343–347).

Ji, K., Tang, G., Pang, H., & Yang, J. (2020). Impedance modeling and analysis of MMC-HVDC for offshore wind farm integration. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery, 35, 1488–1501.

Cai, L., Karaagac, U., & Mahseredjian, J. (2017). Simulation of startup sequence of an offshore wind farm with MMC-HVDC grid connection. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery, 32, 638–646.

Cai, X., & Jing, L. (2015). Impact of controller parameters on stability of MMC-based HVDC systems for offshore wind farms. In 2015 international conference on renewable power generation. October 17–18, 2015, Beijing, China (pp. 1–6).

Kim, G. H., Kang, M. H., Ahn, J. H., Kim, E. H., & Chae, S. H. (2018). Operation of DC series connected offshore wind farm by using tap changing transformer with MMC-HVDC. In 2018 international conference on renewable energy: generation and applications. February 25–28, 2018, Al Ain, UAE (pp. 291–295).

Fan, M., Hui, L. I., & Fan, X. (2018). An improved control strategy for MMC-HVDC offshore wind power grid-connected system. Journal of Beijing Information Science & Technology University, 33(6), 52–57.

Gang, Y., Yi, C. G., Li, D. Z., Dong, D. L., & Xing, L. (2019). Multi-phase permanent magnet synchronous generator variable speed constant frequency offshore wind system based on modular multilevel converter. In 2019 IEEE innovative smart grid technologies-Asia. May 21–24, 2019, Chengdu, China (pp. 2127–2132).

Ma, Z., Wang, X., Wu, S., & Zhang, X. (2019). Coordinated control strategy of offshore wind farm and MMC-HVDC to improve the inertia level of power system. In 2019 IEEE international conference on advanced power system automation and protection. October 21–24, 2019, Xi'an, China (pp. 1819–1823).

Meng, Y., Zou, Y., & Wang, H. (2020). Novel submodule topology with large current operation and DC-fault blocking capability for MMC-HVDC. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery, 36, 1542–1551.

Zhang, J., Li, K. J., & Liu, W. (2021). Grid side reactive power support strategy for MMC-HVDC connected to the wind farms based on unloading resistor. Electric Power Systems Research, 193, 1–11.

Flourentzou, N., Agelidis, V. G., & Demetriades, G. D. (2009). VSC-based HVDC power transmission systems: An overview. IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics, 24, 592–602.

Xu, L., Yao, L., & Bazargan, M. (2009). DC grid management of a multi-terminal HVDC transmission system for large offshore wind farms. In 2009 international conference on sustainable power generation and supply. April 6–7, 2009, Nanjing, China (pp. 1–7).

Liang, J., Oriol, G. B., Janaka, E., Nicholas, J., & Wen, A. (2012). A multi-terminal HVDC transmission system for offshore wind farms with induction generators. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems, 43, 54–62.

Gomis, B. O., Liang, J., & Ekanayake, J. (2011). Topologies of multiterminal HVDC-VSC transmission for large offshore wind farms. Electric Power Systems Research, 81, 271–281.

Zhang, Y. Z., Jayashri, R., John, F., Li, R., & Han, M. X. (2016). Review of modular multilevel converter based multi-terminal HVDC systems for offshore wind power transmission. Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews, 61, 572–586.

Bin, K. J., & Zhi, X. W. (2016). The key technologies of VSC-MTDC and its application in China. Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews, 62, 297–304.

Jef, B., & Ronnie, B. (2012). Modeling and control of multi-terminal VSC HVDC systems. Energy Procedia, 24, 123–130.

Xiong, Y., Yao, W., & Wen, J. (2020). Two-level combined control scheme of VSC-MTDC integrated offshore wind farms for onshore system frequency support. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems, 36, 1–12.

Sandano, R., Farrell, M., & Basu, M. (2017). Enhanced master slave control strategy enabling grid support services and offshore wind power dispatch in a multi-terminal VSC HVDC transmission system. Renewable Energy, 113, 1580–1588.

Li, H., Fan, X., & Liu, S. (2020). A modified control strategy for MMC-MTDC transmission systems. In 2020 IET international conference on AC and DC power transmission. July, 2–3 2020, Online Conference (pp. 1431–1435).

Huang, Z. (2018). Adaptive integrated coordinated control strategy for MMC-MTDC systems. In 2018 international conference on power system technology. November 6–8, 2018, Guangzhou, China (pp. 2440–2447).

Zhang, Y., Cong, W., & Li, G. (2020). Single-ended MMC-MTDC line protection based on dual-frequency amplitude ratio of traveling wave. Electric Power Systems Research, 189, 1–14.

Zhang, S., Zou, G. B., Wang, C. J., Li, J., & Xu, B. (2020). A non-unit boundary protection of DC line for MMC-MTDC grids. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems, 116, 1–9.

Chen, J., Li, L., & Dong, F. (2020). An improved coordination method of multi-terminal MMC-HVDC system suitable for wind farm clusters integration. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems, 117, 1–10.

Zhu, J. B., Campbell, D. B., Grain, P. A., & Andrew, J. R. (2015). Coordinated direct current matching control strategy for multi-terminal DC transmission systems with integrated wind farms. Electric Power Systems Research, 124, 55–64.

Raymundo, E. T. O., Atle, R. A., Hanne, S., Atsede, G. E., Kjell, L., & John, O. T. (2014). Experimental verification of a voltage droop control for grid integration of offshore wind farms using multi-terminal HVDC. Energy Procedia, 53, 104–113.

Wang, W. Y., Yin, X., Jiang, L., Cao, Y. J., & Li, Y. (2021). Perturbation observer-based nonlinear control of VSC-MTDC systems. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems, 134, 1–13.

Leka, A. I., Doumbia, M. L., & Manguelle, J. S. (2020). Onshore control strategy of DC-AC multilevel modular converter of the offshore DC voltage collection. In 2020 international conference on ecological vehicles and renewable energies. September 10–12, 2020, Monte-Carlo, Monaco (pp. 1–7).

Rodrigues, S., Pinto, R. T., Bauer, P., Brys, T., & Nowé, A. (2015). Online distributed voltage control of an offshore MTDC network using reinforcement learning. In 2015 IEEE congress on evolutionary computation. May 25–28, 2015, Sendai, Japan (pp. 1769–1775).

Xu, Z., & Zhang, C. (2015). Optimal direct voltage control of MTDC grids for integration of offshore wind power. In 2015 IEEE innovative smart grid technologies-Asia. November 3–6, 2015, Bangkok, Thailand (pp. 1–6).

Aragüés, P. M., Egea, L. A., Galceran, A. S., et al. (2014). Droop control for loss minimization in HVDC multi-terminal transmission systems for large offshore wind farms. Electric Power Systems Research, 112, 48–55.

Dong, H., Xu, Z., Song, P., et al. (2017). Optimized power redistribution of offshore wind farms integrated VSC-MTDC transmissions after onshore converter outage. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, 64, 8948–8958.

Rink, Y., Wenig, S., Hirsching, C., et al. (2017). Cluster-based DC grid control strategies applied to a European offshore grid scenario. In 2017 international universities power engineering conference. August 28–31, 2017, Heraklion, Greece (pp. 1–6).

Shi, G., Wu, G. X., Cai, X., et al. (2012). Coordinated control of multi-terminal VSC-HVDC transmission for large offshore wind farms. In 2012 proceedings of the international power electronics and motion control conference. June 2–5, 2012, Harbin, China (pp. 1278–1282).

Aragues, P. M., Egea, A. A., Gomis, B. O., et al. (2012). Optimum voltage control for loss minimization in HVDC multi-terminal transmission systems for large offshore wind farms. Electric Power Systems Research, 89, 54–63.

Yadav, O., Kishor, N., & Negi, R. (2019). Power imbalance sharing among the power converters in MTDC system. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems, 109, 584–596.

Xu, Z. (2015). Power flow control of high voltage DC networks for grid integration of offshore wind power. Energy Procedia, 75, 1698–1704.

Zeng, R., Xu, L., Yao, L., et al. (2016). Hybrid HVDC for integrating wind farms with special consideration on commutation failure. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery, 31, 789–797.

Torres, R. E., Molinas, M., & Undeland, T. (2012). Hybrid HVDC connection of large offshore wind farms to the AC grid. In 2012 IEEE international symposium on industrial electronics. May 28–31, 2012, Hangzhou, China (pp. 1591–1597).

Li, G., An, T., Liang, J., et al. (2020). Studies of commutation failures in hybrid LCC/MMC HVDC systems. Global Energy Interconnection, 3(3), 193–204.

Torres, R. E., Garces, A., Molinas, M. et al. (2012). Integration of offshore wind farm using a hybrid HVDC transmission composed by PWM current-source converter and line-commutated converter. In 2012 Asia-Pacific power and energy engineering conference. March 27–29, 2012, Shanghai, China (pp. 1–4).

Xia, B., Li, Y., Li, Z., Xu, F., et al. (2018). DC fault ride through strategy of a PWM-CSC based hybrid HVDC transmission system. In 2018 IEEE international power electronics and application conference and exposition. November 4–7, 2018, Shenzhen, China (pp. 1–6).

Torres, R. E., Molinas, M., & Undeland, T. (2012). Offshore wind farm grid integration by VSC technology with LCC-based HVDC transmission. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy, 3(4), 899–907.

Zhai, D., Han, M., & Xu, S. (2013). Coordination control for offshore wind power sending through hybrid HVDC. In 2013 IEEE grenoble conference. June 16–20, 2013, Grenoble, France (pp. 1–6).

Torres, O. A., & Alejandro, G. B. (2017). Grid integration of offshore wind farms using a Hybrid HVDC composed by an MMC with an LCC-based transmission system. Energy Procedia, 137, 391–400.

Hu, C., Tong, Y., Jing, J., et al. (2020). Research on steady state control strategies of wind farm integration by VSC-LCC hybrid HVDC transmission. Energy Reports, 6, 985–991.

Li, Z., Wei, Z., Zhan, R., et al. (2020). System operational dispatching and scheduling strategy for hybrid cascaded multi-terminal HVDC. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems, 122(3), 1–9.

Li, R., Yu, L., Xu, L., et al. (2019). Coordinated control of parallel DR-HVDC and MMC-HVDC systems for offshore wind energy transmission. IEEE Journal of Emerging and Selected Topics in Power Electronics, 8, 2572–2582.

Li, R., Yu, L., Xu, L., et al. (2018). DC fault protection of diode rectifier unit based HVDC system connecting offshore wind farms. In 2018 IEEE power & energy society general meeting. August 5–10, 2018, Portland, USA (pp. 1–5).

Xie, L., Yao, L., Cheng, F., et al. (2020). Coordinate control strategy for stability operation of offshore wind farm integrated with diode-rectifier HVDC. Global Energy Interconnection, 3(3), 205–216.

Ten, I. F., Bergna, D. G., & Sanchez, S. (2017). Control of HVDC systems based on diode rectifier for offshore wind farm applications. Energy Procedia, 137, 406–413.

Chang, Y., & Xu, C. (2019). Hybrid topology of a diode-rectifier-based HVDC system for offshore wind farms. IEEE Journal of Emerging and Selected Topics in Power Electronics, 7(3), 2116–2128.

Thanh, H. N., & Ngoc, T. Q. (2021). A hybrid HVDC converter based on M2C and diode rectifiers without DC capacitors for offshore wind farm integration. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems, 133, 1–10.

Ge, Y., Xiang, L., Li, Y., He, R., et al. (2020). A novel topology for HVDC link connecting to offshore wind farms. In 2020 IEEE international conference on high voltage engineering and application. September 6–10, 2020, Beijing, China (pp. 1–4).

Kawaguchi, T., Sakazaki, T., Isobe, T., et al. (2013). Offshore-wind-farm configuration using diode rectifier with MERS in current link topology. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, 60(7), 2930–2937.

Ramachandran, R., Poullain, S., Benchaib, A., et al. (2018). AC grid forming by coordinated control of offshore wind farm connected to diode rectifier based HVDC link-review and assessment of solutions. In 2018 European conference on power electronics and applications September 17–21, 2018, Riga, Latvia (pp. 1–10).

Shi, G., Cai, X., Sun, C., et al. (2016). All-DC offshore wind farm with parallel connection: an overview. In 2016 IET international conference on AC and DC power transmission. May 28–29, 2016, Beijing, China (pp. 1–6).

Almeida, A. O., Tomim, M. A., Almeida, P. M., et al. (2020). A control strategy for an offshore wind farm with the generating units connected in series with a VSC-HVDC transmission link. Electric Power Systems Research, 180, 1–13.

Almeida, A. O., Lopes, I. F., Almeida, P. M., et al. (2021). Series-DC connection of offshore wind generating units-modeling, control and galvanic isolation. Electric Power Systems Research, 195, 1–9.

Feng, A., Zhao, B., Cui, B., et al. (2021). Multi-functional DC collector for future ALL-DC offshore wind power system: Concept, scheme, and implement. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIE.2021.3109539

D'Arco, S., Aardal, A. R., & Hernes, M. (2012). Efficiency analysis of non-insulated converters for DC series collection in offshore wind farms. In 2012 international symposium on power electronics power electronics, electrical drives, automation and motion. June 20–22, 2012, Sorrento, Italy (pp. 553–558).

Gang, S., Zhang, J., Xu, C., et al. (2016). Decoupling control of series-connected DC wind turbines with energy storage system for offshore DC wind farm. In 2016 IEEE international symposium on power electronics for distributed generation systems. June 27–30, 2016, Vancouver, Canada (pp. 1–6).

Zhang, H., Gruson, F., Florez, D., et al. (2016). Analysis of the influence of different cable modelling for DC series offshore wind farm. In 2016 European conference on power electronics and applications. September 5–9, 2016, Arlsruhe, Germany (pp. 1–9).

Zhang, H., Florez, D., Saudemont, C., et al. (2016). Improved overvoltage limitation control approach of a DC series offshore wind farm based on MMC. In 2016 mediterranean electrotechnical conference. April 18–20, 2016, Lemesos, Cyprus (pp. 1–6).

Rong, F., Wu, G., Li, X., et al. (2019). ALL-DC offshore wind farm with series-connected wind turbines to overcome unequal wind speeds. IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics, 34, 1370–1381.

Sasongko, F., Hagiwara, M., & Akagi, H. (2013). A front-to-front (FTF) system consisting of two modular multilevel cascade converters based on double-star chopper-cells. In 2013 international future energy electronics conference. November 3–6, 2013, Tainan, Taiwan (pp. 488–493).

Barker, C. D., Davidson, C. C., Trainer, D. R., et al. (2012). Requirements of DC-DC converters to facilitate large DC grids. CIGRE, 204, 1–10.

Zhan, C., Smith, C., Crane, A. et al. (2010). DC transmission and distribution system for a large offshore wind farm. In 2010 IET international conference on AC and DC power transmission. October 19–21, 2010, London (pp. 1–5).

He, J. H., Chen, K., et al. (2020). Review of protection and fault handling for a flexible DC grid. Protection and Control of Modern Power Systems, 5(2), 151–165.

Hiremath, R., & Moger, T. (2021). Transient analysis of LCC based HVDC offshore wind farms using DIGSILENT power factory. In 2021 Iran wind energy conference May 17–18, 2021, Shahrood, Iran (pp. 1–5).

Daoud, M. I., Massoud, A. M., Abdel, A. S., et al. (2016). A flywheel energy storage system for fault ride through support of grid-connected VSC HVDC-based offshore wind farms. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems, 31, 1671–1680.

Vozikis, D., Psaras, V., Alsokhiry, F., et al. (2021). Customized converter for cost-effective and DC-fault resilient HVDC grids. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems, 131, 1–13.

Parker, M., Finney, S., & Holliday, D. (2017). DC protection of a multi-terminal HVDC network featuring offshore wind farms. Energy Procedia, 142, 2195–2201.

Alam, M. S., Al-Ismail, F. S., Abido, M. A., et al. (2021). Fault current limiter of VSC-HVDC systems using variable resistive bridge controller. Ain Shams Engineering Journal, 12, 2643–2654.

Popat, M., Wu, B., Zargari, N. (2012). Fault ride-through of PMSG-based offshore wind farm connected through cascaded current source converter-based HVDC. In 2012 IEEE power electronics and machines in wind applications. July 16–18, 2012, Denver, USA (pp. 1–7).

Li, R., Bozhko, S., et al. (2008). Frequency control design for offshore wind farm grid with LCC-HVDC link connection. IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics, 23, 1085–1092.

Yan, L., Wei, S., Chi, Y. N., et al. (2014). Research on offshore wind farm VSC-HVDC transmission system fault ride through issue. In 2014 international conference on power system technology. October 20–22, 2014, Chengdu, China (pp. 2190–2195).

Sun, W. Y., Raymundo, E. T. O., & Olimpo, A. L. (2016). Investigation on fault-ride through methods for VSC-HVDC connected offshore wind farms. Energy Procedia, 94, 29–36.

Kirakosyan, A., Moursi, M. S. E., & Khadkikar, V. (2017). Fault ride through and grid support topology for the VSC-HVDC connected offshore wind farms. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery, 32, 1592–1604.

Muhammad, R., Aragüés, P. M., & Oriol, G. B. (2018). Short circuit analysis of an offshore AC network having multiple grid forming VSC-HVDC links. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems, 102, 364–380.

Ye, Y., Lu, Z., Le, X. et al. (2018). A coordinated frequency regulation strategy for VSC-HVDC integrated offshore wind farms. In 2018 IEEE power & energy society general meeting. August 5–10, 2018, Portland, USA (pp. 1–5).

Asif, K., Mehdi, S., Ali, R., & Alex, S. (2021). Analytical review on common and state-of-the-art FR strategies for VSC-MTDC integrated offshore wind power plants. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 148, 1–17.

Li, J., Li, Y., Wang, W., et al. (2018). Fault ride through strategy of VSC-MTDC system connected with offshore wind farms. In 2018 IEEE conference on industrial electronics and applications. 31 May–2 June 2018, Wuhan, China (pp. 1756–1761).