Abstract

Background

Prognosis research refers to the investigation of association between a baseline health state, patient characteristic and future outcomes. The findings of several prognostic studies can be summarized in systematic reviews (SRs), but some characteristics of prognostic studies may result in difficulties when performing the analyses. This study aimed to investigate trends in the volume and quality of SRs of prognostic studies in the literature.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review in five high-impact clinical journals (Annals of Internal Medicine, BMJ, Circulation, JAMA, and Stroke) to identify SRs of prognosis studies focused on fundamental prognosis research and prognostic factor research published between 2000 and 2012. We excluded studies of clinical prediction guides or implementation studies. The quality of the SRs was rated based on the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) and the PRISMA checklists.

Results

Over the 13-year period, 1065 SRs were published. Of these, 198 were SRs of prognosis studies. The proportion of all SRs to published articles increased from 0.86% in 2000 to 4.2% in 2012. Likewise, the proportion of prognosis SRs to all SRs increased from 10.3% in 2000 to 17.7% in 2012. MOOSE and PRISMA mean summary scores consistently increased over time for all journals, indicating that the quality of reporting in these SRs has steadily improved. However, several items were not consistently well reported by investigators.

Conclusions

This study shows that there is a growing number of SRs of prognosis studies. However, the quality is suboptimal when assessed with the generic reporting guidelines for observational studies. New reporting guidelines and risk of bias tools for prognosis studies are needed to improve the quality of future research in this field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Broadly speaking, prognosis research focuses on the description and prediction of future outcomes in people with a given baseline health state [1]. Its aim is to understand and improve outcomes in people with a specific disease or health condition and to provide evidence for improving healthcare and public health policy. As such, prognosis research can provide important information to support clinical decision-making, the definition of risk groups, and more accurate prediction of disease outcomes [2]. It can help to extend or revise definitions of disease, while identifying unanticipated benefits or harms of healthcare interventions and the need for new interventions to improve patient outcomes [3]. It also has an important role in helping patients to make healthcare-related decisions and planning their lives based on their preferences and reliable evidence [4].

The purpose of this study was to assess the quality of SRs of prognostic studies published over the last decade in five high-impact journals. The prognosis research strategy (PROGRESS) group suggests that prognosis research can be generally classified into four categories:

-

(1)

Fundamental prognosis research (to describe and explain future outcomes in relation to current diagnostic and treatment practices) [1].

-

(2)

Prognostic factor research (to identify factors associated with subsequent clinical outcomes in patients with a particular disease or health condition) [5].

-

(3)

Prognostic model research (to explore the use of combinations of prognostic factors to predict the risk of future clinical outcomes in individual patients) [6].

-

(4)

Stratified medicine research (to identify factors that predict patient treatment response, commonly referred to as predictive factors) [7].

This study will focus on the first two categories: fundamental prognosis research to describe and explain outcomes in patients with a given disease or condition and research on prognostic factors associated with outcomes. We chose to focus on these more traditional studies of prognosis because the latter two types (prediction models and stratified medicine research) comprise rapidly expanding and evolving fields and as such are beyond the scope of this study.

SRs aim to summarize the collection of primary studies on a given topic. A common issue when conducting SRs is the limitations of the primary studies included in the review and such is the case in SRs of prognosis studies [8]. Prognosis studies are often too small and too poorly designed and/or analyzed to provide reliable evidence. An increasing body of evidence highlights the limitations of primary studies of prognosis, including those inherent to the retrospective design of many studies, variations in inclusion criteria, and variables included in adjusted analyses, inadequate reporting methods, and differences in how results are reported [9, 10].

SRs can help to identify the strengths and limitations of research in a specific field. The purpose of this study was to identify the number of SRs of prognosis studies published over a 13-year period in five high-impact journals and to assess the quality of these reviews.

Methods

Inclusion criteria

SRs of prognosis studies were included if they were summarized primary prognosis study types 1 or 2, as defined by PROGRESS—that is, studies reporting on the overall prognosis of a broad population of patients with a specific health condition, or assessment of one or more prognostic variables. SRs of diagnosis, clinical prediction models, or implementation studies were excluded. We also excluded narrative reviews, and non-systematic reviews published as editorials or letters.

Literature search

We conducted a Medline search to identify SRs published from 2000 to 2012 in five high-impact journals in internal medicine and cardiovascular disease (Annals of Internal Medicine, BMJ, Circulation, JAMA, and Stroke). Search details are provided in the Appendix.

Study selection

Pairs of authors independently examined in duplicate the titles and abstracts of retrieved references to identify SRs of prognosis studies fulfilling our inclusion criteria. Disagreements among the authors were resolved by consensus. The full texts of all selected articles were obtained, and pairs of authors examined, in duplicate, the eligibility of each article for inclusion; in cases of disagreement, a third independent reader was involved.

Quality assessment

The methodologies to conduct SRs of prognosis are not yet fully developed, and no agreement exists on the key features defining good quality research in this field [9, 10]. Therefore, we used the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) [11] and the MOOSE (Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) checklists [12] as a proxy for the quality of the included SRs of prognosis studies. Pairs of researchers assessed each of the included SRs in duplicate using the two checklists. Each item in the checklist was rated defining it as present/absent (or completed/incomplete) or not applicable (NA). In cases of disagreement, a third independent reader was involved.

Statistical analysis

Summary descriptive statistics were used to report the number of SRs as proportion of all research articles as well as the number of SRs of prognosis as a proportion of all SRs.

The proportion of systematic reviews that met individual items from the MOOSE and PRISMA checklists by year was reported with 95% confidence interval (CIs). Summary scores for each review were calculated as the sum of the scores for each item divided by total number of the items in the checklists. Mean summary scores with 95% CIs were reported separately for MOOSE and PRISMA checklists by journal and year of publication. Higher scores indicated more completed items. The change in mean MOOSE and PRISMA scores by year was calculated using ANOVA tests and linear regression.

Results

Bibliometric indexes

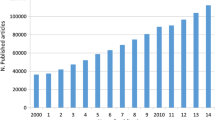

Over the 13-year search period, 41,996 research articles were published in the five selected journals. One thousand sixty-five SRs were published, of which, 198 met our inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Figure 2 shows the trend over time for all SRs as a proportion of total research articles, while Fig. 3 shows the trend over time of SRs of prognosis as a proportion of all SRs. Overall, the proportion of all SRs increased from 0.86% in 2000 to 4.2% in 2012. Likewise, the proportion of prognostic SRs to overall SRs slightly increased from 10.3% in 2000 to 17.7% in 2012. Characteristics of the included SRs are reported in Table 1.

Temporal trend of prognostic systematic reviews as a percentage of total published systematic reviews. The figure shows the temporal trend of prognostic systematic reviews expressed as percentage of all systematic reviews published in Annals of Internal Medicine, BMJ Circulation, JAMA, and Stroke from 2000 to 2012

Quality assessment of SRs of prognosis

Tables 2 and 3 show the proportion of reviews meeting each individual MOOSE and PRISMA item, respectively. The MOOSE and PRISMA items are reported in Additional file 1: Tables S1 and S2. Items from MOOSE that most often were not met were description of study population, qualification of searchers, effort to include all available studies, software used, list of excluded citations with justification, addressing articles published in other languages other than English, methods of handling unpublished studies, assessment of confounding, assessment of study quality and risk of bias, provision of appropriate tables and graphic, and consideration of alternative explanations for the results. Items from PRISMA that most often were not met were description of review protocol, search strategy, method of data extraction, method of assessing risk of bias, method of additional analysis, and presentation of risk of bias.

Figures 4 and 5 show by journal the temporal trend of mean summary scores for MOOSE and PRISMA checklists, respectively. Significant differences were found for mean score by year for both MOOSE (p = 0.02) and PRISMA (p = 0.01). However, a positive correlation was found between year of publication and increase in mean PRISMA score (coefficient = 0.03, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.06, p = 0.02) but not for mean MOOSE score (coefficient = 0.02, 95% CI −0.01 to 0.04, p = 0.14). The trend over time of mean summary scores was consistently upward for all journals but most evident for BMJ (MOOSE 0.26 [CI 95% 0.12 to 0.39] in 2000 to 0.89 [CI 95% 0.83 to 0.95] in 2012; PRISMA 0.35 [CI 95% 0.19 to 0.51] in 2000 to 0.91 [CI 95% 0.87 to 0.95] in 2012).

Discussion

In a subset of five high-impact clinical journals, the percentage of published research articles with the Medline publication type (PT) of “Systematic Review” increased five-fold, from 0.86% to 4.2% over 13 years (2000–2012). In the same time frame, the relative percentage of SRs of prognosis remained roughly stable at 20%. As a result, the absolute number of SRs of prognosis has been constantly increasing over time, with a total of 198 published between 2000 and 2012 in JAMA, Annals of Internal Medicine, BMJ, Circulation, and Stroke.

A moderate but progressive improvement in the quality of reporting was observed over time and across the journals considered. However, we found that most of the SRs did not assess the risk for confounding and its possible effect on the direction, strength, and generalizability of the observed association. Confouding may become particularly relevant when prognostic factors are used to tailor treatment decisions to specific populations [13, 14]. We suggest that confounding should be more carefully and systematically evaluated for non-randomized studies assessing prognostic factors, which may require developing dedicated risk of bias assessment tools. Moreover, common mandatory items (e.g., handling of unpublished data, risk of bias assessment, sensitivity analysis.) were poorly reported in SRs of prognostic studies. These limitations should be considered by researchers and reviewers in order to improve the quality of reviews in this field.

We intentionally adopted a non-specific approach to SR appraisal given the various scopes of prognostic research. We focused our study on the first two categories of prognosis research as defined by the PROGRESS group [1] and excluded the latter two categories (clinical prediction models and stratified medicine research). There is increasing information on how and when to perform (or sometimes not perform) a SR of type 1 or 2 studies; summarizing the evidence on clinical prediction models is much more complicated and largely a developing field at this time.

The results presented about assessment and improvement of reporting should be considered in the framework of current research streams in the field. On one side, researchers are focusing on proposing and testing risk of bias assessment tools (QUIPS for studies of risk factors [15] and PROBAST for clinical prediction models, yet unpublished) and specifically on understanding the potential benefits and limitations of SRs and meta-analyses of PROGRESS type 1 (overall prognosis) and PROGRESS type 2 (risk factors) studies [5]. On the other side, GRADE working group members have proposed criteria to assess confidence in SR estimates for type 1 studies, which can improve the use of baseline risk information [2, 4] and of risk factors, which can support planning and execution of subgroup analyses in randomized controlled trials and SRs of randomized controlled trials [15]. In the meantime, it seems appropriate to avoid inundating such a fluidly evolving field [16] with additional ad hoc reporting guidelines, when appropriate use of validated instruments such as MOOSE and PRISMA is far from routine. Eventually, focusing on quality items critical to prognostic research and those that have been difficult to achieve, as shown by our analysis, might be the most efficient way to move forward.

Some limitations of our analysis are worth discussion. First, we limited our sample to five major clinical journals. We cannot extrapolate beyond their content coverage, but we have no reason to expect that important reviews in internal medicine and subspecialties are more likely to be found elsewhere. However, replication of our analyses in different journal sets would be informative. Second, we did not perform a separate analysis of the different types of prognosis studies defined by the PROGRESS group; we cannot draw any conclusions on differences between SR of type 1 and 2 studies. We fully acknowledge the value of the classification in streamlining research in the field, but we consider it premature to look for differences in reporting by study type. In addition, the MOOSE checklist was published in 2000, whereas the PRISMA checklist was not published until 2009. Therefore, it is possible that improvements in the conduct and reporting of SRs might be partially explained by the effects of the publication of PRISMA. Third, we adopted a resource-wise approach and were more interested in appraising the quality of the SRs than the quality and usability of the quality assessment instruments. For this reason, we embedded in our process an initial calibration step to ensure that all the raters were referring to the same scale and were aligned. After that, we rotated all pairs of raters and all raters assessed a similar proportion of articles from each journal. For disagreements, we proceeded immediately to adjudication by a third reviewer. We did not collect information needed to formally calculate a measure of agreement.

Conclusions

Although many limitations impair the process of evidence synthesis in the field of prognosis, contemporary trends of clinical research toward tailored treatment and patient-centered research make the role of prognosis research even more central. Better evidence relating to disease prognosis will facilitate our understanding of how to move from proof of efficacy to personalized medicine. We found that the quality of SRs of prognosis is suboptimal as assessed using generic reporting guidelines for observational studies. This is in part due to suboptimal reporting, which has been partially reduced over time, and potentially by the imperfect fit of the instruments to assess a very specialized typology of studies. New reporting guidelines and risk of bias tools have been recently (or will soon be) made available for clinical prediction models. Whether these same tools will be suitable to improve the quality of PROGRESS type 1 and 2 studies remains to be investigated. Monitoring of the quality of prognostic studies and their reporting will continue to be important to ensure improvement in the field. Ideally, a repository of critically appraised SRs of prognosis might provide a source of useful examples to guide future investigations.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- MOOSE:

-

Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology

- NA:

-

Not applicable

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SR:

-

Systematic review

References

Hemingway H, Croft P, Perel P, Hayden JA, Abrams K, Timmis A, Briggs A, Udumyan R, Moons KG, Steyerberg EW, et al. Prognosis research strategy (PROGRESS) 1: a framework for researching clinical outcomes. BMJ. 2013;346:e5595.

Spencer FA, Iorio A, You J, Murad MH, Schunemann HJ, Vandvik PO, Crowther MA, Pottie K, Lang ES, Meerpohl JJ, et al. Uncertainties in baseline risk estimates and confidence in treatment effects. BMJ. 2012;345:e7401.

Moons KG, Royston P, Vergouwe Y, Grobbee DE, Altman DG. Prognosis and prognostic research: what, why, and how? BMJ. 2009;338:b375.

Iorio A, Spencer FA, Falavigna M, Alba C, Lang E, Burnand B, McGinn T, Hayden J, Williams K, Shea B, et al. Use of GRADE for assessment of evidence about prognosis: rating confidence in estimates of event rates in broad categories of patients. BMJ. 2015;350:h870.

Riley RD, Hayden JA, Steyerberg EW, Moons KG, Abrams K, Kyzas PA, Malats N, Briggs A, Schroter S, Altman DG, et al. Prognosis research strategy (PROGRESS) 2: prognostic factor research. PLoS Med. 2013;10(2):e1001380.

Steyerberg EW, Moons KG, van der Windt DA, Hayden JA, Perel P, Schroter S, Riley RD, Hemingway H, Altman DG, Group P. Prognosis research strategy (PROGRESS) 3: prognostic model research. PLoS Med. 2013;10(2):e1001381.

Hingorani AD, Windt DA, Riley RD, Abrams K, Moons KG, Steyerberg EW, Schroter S, Sauerbrei W, Altman DG, Hemingway H, et al. Prognosis research strategy (PROGRESS) 4: stratified medicine research. BMJ. 2013;346:e5793.

Riley RD, Sauerbrei W, Altman DG. Prognostic markers in cancer: the evolution of evidence from single studies to meta-analysis, and beyond. Br J Cancer. 2009;100(8):1219–29.

Hemingway H, Riley RD, Altman DG. Ten steps towards improving prognosis research. BMJ. 2009;339:b4184.

Hemingway H, Philipson P, Chen R, Fitzpatrick NK, Damant J, Shipley M, Abrams KR, Moreno S, McAllister KS, Palmer S, et al. Evaluating the quality of research into a single prognostic biomarker: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 83 studies of C-reactive protein in stable coronary artery disease. PLoS Med. 2010;7(6):e1000286.

Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart LA, Group P-P. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;349:g7647.

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–12.

Grobbee DE, Hoes AW. Confounding and indication for treatment in evaluation of drug treatment for hypertension. BMJ. 1997;315(7116):1151–4.

Walker AM. Confounding by indication. Epidemiology. 1996;7(4):335–6.

Hayden JA, van der Windt DA, Cartwright JL, Cote P, Bombardier C. Assessing bias in studies of prognostic factors. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(4):280–6.

Vandenbroucke JP. STREGA, STROBE, STARD, SQUIRE, MOOSE, PRISMA, GNOSIS, TREND, ORION, COREQ, QUOROM, REMARK… CONSORT: for whom does the guideline toll? J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(6):594–6.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset upon for the analysis reported in this manuscript is available from the author upon request.

Authors’ contributions

DM and AI designed the study, developed the methodology, collected the data, and analyzed the data. DM and AI wrote the manuscript. All the authors took part in the discussion of results and in revising the draft manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1:

PRISMA checklist. (PPTX 53 kb)

Appendix

Appendix

Literature search

The following search string was used: (“Circulation” [Journal] OR “BMJ (Clinical research ed.)” [Journal] OR “Annals of internal medicine” [Journal] OR “Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation” [Journal] OR “JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association” [Journal]) AND ((“2000/01/01” [PDAT]: “2012/12/31” [PDAT]); the search was performed with and without ANDing the term “review” [Publication Type]).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Matino, D., Chai-Adisaksopha, C. & Iorio, A. Systematic reviews of prognosis studies: a critical appraisal of five core clinical journals. Diagn Progn Res 1, 9 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41512-017-0008-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41512-017-0008-z