Abstract

Background

People living with HIV (PLWH) are prone to develop sub-clinical Cardiovascular (CV) disease, despite the effectiveness of combined Antiretroviral Therapy (cART). Algorithms developed to predict CV risk in the general population could be inaccurate when applied to PLWH. Myocardial Extra-Cellular Matrix (ECM) expansion, measured by computed tomography, has been associated with an increased CV vulnerability in HIV-negative population. Measurement of Myocardial Extra-Cellular Volume (ECV) by computed tomography or magnetic resonance, is considered a useful surrogate for clinical evaluation of ECM expansion. In the present study, we aimed to determine the extent of cardiovascular involvement in asymptomatic HIV-infected patients with the use of a comprehensive cardiac computed tomography (CCT) approach.

Materials and methods

In the present study, ECV in low atherosclerotic CV risk PLWH was compared with ECV of age and gender matched HIV- individuals. 53 asymptomatic HIV + individuals (45 males, age 48 (42.5–48) years) on effective cART (CD4 + cell count: 450 cells/µL (IQR: 328–750); plasma HIV RNA: <37 copies/ml in all subjects) and 18 age and gender matched controls (14 males, age 55 (44.5–56) years) were retrospectively enrolled. All participants underwent CCT protocol to obtain native and postcontrast Hounsfield unit values of blood and myocardium, ECM was calculated accordingly.

Results

The ECV was significantly higher in HIV + patients than in the control group (ECV: 31% (IQR: 28%-31%) vs. 27.4% (IQR: 25%-28%), p < 0.001). The duration of cART (standardized β = 0.56 (0.33–0.95), p = 0.014) and the years of exposure to HIV infection (standardized β = 0.53 (0.4–0.92), p < 0.001), were positively and strongly associated with ECV values. Differences in ECV (p < 0.001) were also observed regarding the duration of cART exposure (< 5 years, 5–10 years and > 10 years). Moreover, ECV was independently associated with age of participants (standardized β = 0.42 (0.33–0.89), p = 0.084).

Conclusions

HIV infection and exposure to antiretrovirals play a detrimental role on ECV expansion. An increase in ECV indicates ECM expansion, which has been associated to a higher CV risk in the general population. The non-invasive evaluation of ECM trough ECV could represent an important tool to further understand the relationship between HIV infection, cardiac pathophysiology and the increased CV risk observed in PLWH.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Myocardial Extra-Cellular Matrix (ECM) is a complex biological network consisting of a wide variety of proteins (principally glycoproteins, proteoglycans, and glycosaminoglycans) in which cardiac myocytes, fibroblasts, vascular cells, and leukocytes dwell. ECM proteins participate to myocardial strength and plasticity and play a fundamental role in cardiac development, homeostasis, and remodelling [1]. ECM alterations may indicate a loss of cardiac morphological homeostasis and may represent an indicator of Cardiovascular Diseases (CVD). ECM expansion has been linked to electrical, mechanical and vasomotor dysfunctions, cardiac fibrosis and, eventually, increased mortality [2, 3]. Contrast enhanced Cardiac Computed Tomography (CCT) and Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (CMR) use extracellular extravascular contrast agents to non-invasively quantify the myocardial Extra-Cellular Volume (ECV) [3,4,5,6]. In particular, CCT is increasingly used in experimental and clinical setting, due to its opportunity to assess lots of cardiac features other than ECV and fibrosis (such as coronary anatomy, calcification etc.) in a very shorter time and with a higher spatial resolution than MRI [4, 5].

Although combined Antiretroviral Therapy (cART) has improved both the length and quality of life of people living with HIV (PLWH), cardiovascular diseases represent a challenge for clinicians and are still a leading cause of death in this population. Several studies have shown an increased frequency of coronary atherosclerotic disease, myocardial infarction, arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death (SCD) in PLWH [7]. Interestingly, recent studies have shown that severe CV diseases are more frequent than expected in PLWH with a low Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD) score, possibly as a result of premature aging due to inflammation, immune-activation, cART side effects and direct viral effect [8]. Therefore, algorithms developed to predict CV risk in the general population could be inaccurate when applied to PLWH [9]. In this scenario, the aim of our study was to assess ECV in PLWH with low-ASCVD score and to compare ECV of HIV + subjects to that of a control group.

Methods

Patient population

PLWH with low-ASCVD score and healthy HIV- controls were enrolled in this retrospective, monocentric study. 53 PLWH with low-ASCVD score and 18 healthy controls were consecutively and retrospectively enrolled. Clinical history, anthropometric data, as well as cardiovascular and metabolic data were collected. All HIV + participants underwent contrast enhanced CCT for clinical purposes. Criteria for patient’s inclusion were: (i) Patients in our population were all HIV mono-infected, (ii) preserved glomerular filtration rate, (iii) absence of contraindications to perform CCT and (iv) completion of an iodine enhanced CCT scan after patient written consent acquisition. Exclusion criteria were: (i) known or suspected cardiac amyloidosis (causing interstitium expansion independently of myocardial fibrosis), (ii) hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, (iii) adult congenital heart disease. Demographics and anamnestic data, including information on HIV status and major cardiovascular risk factors were collected and registered. Vital status was ascertained by Social Security Death Index queries and medical record review. A previous history of heart failure (HF), defined according to current guidelines, was considered in presence of physician documentation: (i) documented symptoms (e.g. shortness of breath, fatigue, orthopnoea) and physical signs (e.g. edema, rales) consistent with HF; (ii) supporting clinical findings (e.g. pulmonary edema on chest X-ray), or (iii) therapy for HF (including diuretics, digitalis, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, or beta blockers).

The 18 control subjects enrolled consisted of outpatients referred to CCT for nonspecific thoracic pain, with no history of previous cardiovascular diseases, non-smokers nor under vasoactive therapy and with a previous documented negative ECG. Selection on individuals in the control group was conducted with age and gender matching criteria. All clinical investigations and laboratory exams were performed no more than 7 days before CCT. Review board and the local ethics committee provided approval for this investigation and informed consent was obtained from all patients.

CT image analysis

Pre- and post-contrast Hounsfield Unit (HU) were measured on CT images by the Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS). The regions of interest (ROIs) were drawn firstly on the contrast image at the myocardial septum, in the equilibrium phase, and within the left ventricular chamber, the mean area was about 3 cm2 (range: 1.5–5 cm2). ROIs were then copied to the pre-contrast image. Mean attenuation at the ROI was recorded in HU and Myocardial ECV fraction was calculated using the following (Eq. 1, 2)

where the contrast agent (CA) partition coefficient (λ) represents the ratio of the change (ΔHU) between myocardium and blood, and HCT is the hematocrit level. ΔHU was determined as ΔHU = HUpost - HUpre, where HUpost and HUpre are attenuation after and before administration of iodinated contrast material, respectively. CT examinations were performed with coronary angiography protocol with a 64-detector Dual-source CT scanner (Somatom Definition Siemens Medical Solution, Forehheimen, Germany). Cardiac scans (tube voltage, 120 kV; tube current time product, 190 mAs; section collimation, 64 detector rows, 1.2-mm section thickness; gantry rotation time, 330 ms) were acquired with prospective gating (65%-75% of R-R interval) and reconstructed into 3 mm-thick axial sections, using a B20f kernel. All patients underwent equilibrium CT, with a mean calculated effective dose of 2.18 ± 0.26 mSv and a mean iohexol volume of 150.4 ± 20.4 mL.

Virological analysis

HIV-1 RNA copy numbers were evaluated in plasma samples collected from whole blood obtained in EDTA-containing tubes and stored at -80˚C. Levels of HIV-RNA were measured with Versant kPCR (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostic Inc., Tarrytown, NY) with a detection limit of 37 copies/mL.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were summarized as absolute frequency (and/or percentage), and continuous variables were summarized as mean and Standard Deviation (± SD) or median and inter-quartile range (IQR: 25th and 75th percentile). Chi-square test (with a cell count are greater than 5) or Fisher exact test (with a cell count are equal to or less than 5) compared categorical variables. Mann-Whitney test compared continuous variables, since some continuous variables exhibited skewed distributions on visual inspection. Instead, the independent Student t-test were used to compare normally distributed variables. Besides, linear regression models were used for univariate and multivariate analysis to evaluate the correlation between quantitative ECV and other study parameters. Lastly, One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for multiple-group comparisons according to four categories, followed by Bonferroni test. When interpreting the results, a p-value of less than 0.05 was considered indicative of a significant difference. Statistical analyses were performed using statistical Program for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 20) software package.

Results

General characteristics

A total of 71 subjects were included in the present study (18 controls and 53 asymptomatic HIV-positive patients). The main characteristics of participants are summarised in Table 1 (anthropometrics, CV risk factors, metabolic status, immune-virologic status of HIV + subjects). No significant differences were found between the two groups in terms of gender distribution, age, and other major risk factors (p > 0.05). All enrolled PLWH were free from metabolic syndrome and had no statistically significant differences compared to controls in relation to this issue. Severity of HIV disease was categorized following the Center for Diseases Control and Prevention classification: 20 (38%) patients were in category A2, 10 (19%) patients in category A3, 2 (4%) patients in category B3, 3 (6%) patients in category C2 and 18 (34%) patients in category C3. Median CD4 + nadir before initiation of cART was 181 (IQR: 94–300) cells/µL. During their therapeutic history, 38 of the 53 HIV + participants received at least one protease inhibitor (PI) for a median of 3 (IQR: 0–14) years, while 23 HIV + received a nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) for a median of 1 (IQR: 0–9) years. With cART, plasma viremia was undetectable (lower limit of detection of 37 copies/mL) in all HIV + subjects. The hematocrit value was 35 ± 4% in HIV + participants and 41 ± 3% in controls (p = 0.122). No significant differences were observed regarding Heart Rate (HR) during CCT examination (p = 0.211). Al PLWH enrolled were HIV mono-infected subjects.

Measurements of myocardial extracellular volume fraction

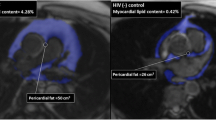

The median ECV value was 27.4% (IQR: 25%-28%) in healthy controls and 31% (IQR: 28%-31%) in HIV + participants, respectively. In our study population, ECV differed significantly between the two groups (p < 0.001), thus indicating the presence of ECV expansion in the myocardium of HIV + subjects (Fig. 1a and b).

ECV values were not affected by patient’s age neither in the HIV + group (r = 0.12, p = 0.145. Figure 2a) or in controls (r = 0.11, p = 0.102). On the contrary, ECV was found to significantly correlate with the number of years of exposure to HIV infection (r = 0.54, p < 0.001. Figure 2b), and the years on cART (r = 0.62, p < 0.001. Figure 2c), showing a trend toward ECV expansion over time in HIV infected patients.

Scatter plots and best-fit regression curves (Solid line) with 95% CI bands (shown as dashed lines) of ECV versus age (a), years of therapy (b), and years of exposure to HIV (c) are shown for HIV+ patients. r and p-value are also reported. Red shading denotes the ECV range of the disease zone. Reference intervals are defined from the work of Scully et al. [3]

Based on the years on cART and years of exposure to HIV, all HIV + patients were divided into three groups: (A) < 5 years, (B) 5 to 10 years and (C) > 10 years. (There was a significant difference in ECV (ANOVA, p < 0.001) among controls and groups (see Table 2).

The multivariable stepwise linear regression showed that the duration of therapy (β was 0.56 (0.33–0.95), p = 0.014) and years of HIV infection (β was 0.53(0.4–0.92), p < 0.001) were independent predictors of ECV expansion (Table 3).

Discussion

Given the efficacy of newer, effective antiretroviral therapies, life expectancy of PLWH has shown a widespread improvement; on the other hand, following the introduction of cART, CVD and cardiovascular deaths have increased dramatically among this population [7]. Several studies conducted in PLWH with CCT angiography, showed an increased presence and extent of coronary artery disease, including non-calcified and high-risk coronary plaques, that were associated with an increase in indicators of systemic immune activation [10, 11].

In a previous work, increased myocardial inflammation has been described in HIV + patients [12]. Specifically in an interesting prospective study, Luetkens et al. that compared the results of comprehensive CMR studies in HIV + asymptomatic patients and controls and observed an increase in CMR markers of myocardial inflammation in the HIV + group, thus suggesting the presence of subclinical myocardial inflammation in this population, which may in the end lead to the impairment of left ventricular myocardial function. The major limitation of the cited study, as well as of our present study, is that no histological assessment has been carried out. Luetkens et al. suggested that, although direct HIV infection of myocytes is rare, it is possible that HIV itself together with other cardiotropic viral infections may lead to myocarditis and to a subsequent left ventricular dysfunction; this may also explain the high rate, observed among this population, of resting ECG abnormalities that are consistent with myocardial damage. Authors suggested that inflammatory condition and subsequent fibrosis may be responsible of the observed CMR findings. On the other hand, our results show relevant differences in respect to those of Luetkens et al. Firstly, the statistical evaluation carried out by our colleagues is mainly descriptive and no regression analysis was performed due of the limited sample size. Moreover, since the study was conceived for preliminary investigation purposes, no correction analysis was performed, possibly leading to inflated type I errors. This assumption in our work is supported by a significant difference in ECV values between the different patient groups, which are known to represent an indirect measure of diffuse interstitial myocardial fibrosis or most serious heart diseases [13]. In addition, the ECV values observed in our study were consistent with previous studies conducted in the HIV- population [14]. Lastly, in our study, due to a larger sample size, we were able to perform a multivariate regression analysis.

It has been described previously that amyloid precursor protein (APP) may be an innate antiviral defence factor in macrophages and microglia that restricts HIV-1 release in the neurological environment [15]. Highly expressed in macrophages and microglia, the membrane-associated APP binds the HIV-1 Gag polyprotein and blocks HIV-1 production and spread. To escape this restriction, Gag promotes secretase-dependent cleavage of APP, resulting in the overproduction of toxic Aβ isoforms. From a neuro-physiopathological point of view, this Gag-mediated Aβ production results in increased degeneration of primary cortical neurons. One interesting question is: could this mechanism be involved in the physiopathology of our findings of an increase in ECV? Could amyloid formation as a result of immunological response to virus in cardiovascular tissue explain cardiomyopathy and peripheral obstructive vascular lesions observed in HIV + patients? Urgent studies are clearly needed to better understand the complex dynamic that underlies the multiple peculiar features which are increasingly being observed in people chronically living with HIV, in order to design effective prevention strategies to counteract the increasing burden of cardiovascular events in our patients.

Overall, these data suggest that an increase in systemic inflammation and immune activation may manifest as a premature CVD phenotype, including disease in large and small vascular beds in patients with HIV. Among PLWH, a relevant concern is whether scores that rely on traditional CV risk factors can accurately identify those individuals with a higher probability to develop CVD (9). In this study, we highlight that PLWH with low-ASCVD risk score are likely to suffer from a silent cardiac impairment. In fact, we found a significant difference in ECV levels between PLWH and healthy subjects (p < 0.001), indicating the presence of ECM expansion in patients with HIV infection. More importantly, years of exposure to HIV, and years of antiretroviral therapy significantly correlated with ECV expansion.

Quantification of ECM is an indirect measure of the expansion of extracellular matrix since, in absence of confounding conditions (e.g. oedema or amyloid), it is related to collagen excess in the interstitium. ECM expansion may therefore indicate vulnerable myocardium in PLWH and represent a potential therapeutic target [7, 16]. Indeed, abnormal fibrosis may be the underlying pathological finding in many cardiovascular disorders, particularly in sudden cardiac deaths (SCD), an emerging issue in PLWH. Frieberg et al. report that PLWH had a 14% higher risk of SCD, with uncontrolled HIV infection representing a risk factor [17]. Recently, a review of the health records from San Francisco between 2011 and 2016 outlined that the cause of death for autopsy-defined sudden arrhythmic death syndrome (SADS) and SCD were 83% and 82% higher respectively in the PLWH than in general population. Interestingly, the histologic exam identified higher rates of cardiac fibrosis in PLWH underling the excess risk of SADS [18]. Indeed, specific tools are sought to measure in vivo the CV risk excess of PLWH which cannot be determined by common predictors of CV scores. Quantifying ECM expansion through ECV assessment may ultimately provide a basis to improve care in HIV individuals through a better risk stratification and the possibility of targeted treatment.

This study has several limitations: first of all, this is a retrospective, monocentric study. Other possible methodological limitations are the small sample size and the lack of prior research studies on the topic. Finally, despite ECV expansion has a multifactorial pathogenesis, we analysed only some specific issues: for example, the possible impact of drug resistance had not considered in this study. Moreover, it is not possible to exclude the contribution of single antiretroviral molecules and/or pharmacological classes to the ECV expansion. At the moment, however, there are no studies aimed at identifying the possible contribution of different drugs to the emergence of the problem. Even this study is unable to answer this question as a much larger sample size is needed to identify any differences related to the different therapies. On the other hand, it is known that some antiretrovirals can participate in the etiopathogenesis of cardiac alterations in PLWH and this aspect reinforces the need for further investigation.

Conclusions

This study investigated the role of ECV measurements in the phenotypic characterization of CV risk, demonstrating that ECV can be easily and non-invasively assessed by CT-scan and used to characterize myocardial stiffness, a clear advantage with respect to alternative methodologies [9]. ECV could provide an important imaging tool to further understand the relationship between cardiac anatomy and heart function.

HIV-positive subjects present ECV expansion in the myocardium. The duration of therapy and years of HIV infection are predictors of myocardial ECV expansion. Imaging technique in PLWH may be critical to identify patients with subclinical CVD and at risk for increased SCD and SAD events, where traditional risk scores may be inaccurate. Our data show that the measurement of ECV is a promising approach to identify asymptomatic patients with high risk of CV diseases despite a low-ASCVD traditional score risk prediction.

Our findings, therefore, may help to explain the increased cardiac morbidity and mortality observed in patients with chronic HIV infection.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- APP:

-

Amyloid precursor protein

- ASCVD:

-

Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease

- BMI:

-

Body mass Index

- CCT:

-

Cardiac computed tomography

- CV:

-

Cardiovascular

- cART:

-

Combined Antiretroviral Therapy

- CA:

-

Contrast agent

- ECM:

-

Extra-Cellular Matrix

- ECV:

-

Extra-Cellular Volume

- HDL:

-

High Density Lipoprotein

- HR:

-

Heart Rate

- HU:

-

Hounsfield Unit

- NNRTI:

-

Nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor

- PLWH:

-

People living with HIV

- PACS:

-

Picture Archiving and Communication System

- PI:

-

Protease inhibitor

- ROIs:

-

Regions of interest

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

- SADS:

-

Sudden arrhythmic death syndrome

- SCD:

-

Sudden cardiac death

References

Rienks M, Papageorgiou AP, Frangogiannis NG, Heymans S. Myocardial extracellular matrix: an ever-changing and diverse entity. Circ Res. 2014;114(5):872–88.

Schelbert EB, Fonarow GC, Bonow RO, Butler J, Gheorghiade M. Therapeutic targets in heart failure: refocusing on the myocardial interstitium. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(21):2188–98.

Wong TC, Piehler KM, Kang IA, Kadakkal A, Kellman P, Schwartzman DS, Mulukutla SR, Simon MA, Shroff SG, Kuller LH, Schelbert EB. Myocardial extracellular volume fraction quantified by cardiovascular magnetic resonance is increased in diabetes and associated with mortality and incident heart failure admission. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(10):657–64.

Altabella L, Borrazzo C, Carnì M, Galea N, Francone M, Fiorelli A. Carbone I. A feasible and automatic free tool for T1 and ECV mapping. Phy Med. 2017;33:47–55.

Borrazzo C, Pacilio M, Galea N, Preziosi E, Carnì M, Francone M. Carbone I. T1 and extracellular volume fraction mapping in cardiac magnetic resonance: estimation of accuracy and precision of a novel algorithm. Phys Med Biol. 2019;64(4):04NT06.

Scully PR, Bastarrika G, Moon JC, Treibel TA. Myocardial extracellular volume quantification by cardiovascular magnetic resonance and computed tomography. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2018;20(3):15.

Shah ASV, Stelzle D, Lee KK, Beck EJ, Alam S, Clifford S, Longenecker CT, Strachan F, Whiteley W, Rajagopalan S, Nair H, Newby DE. McAllister D. A. Global Burden of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease in People Living With HIV. Circulation. 2018;138(11):1100–12.

Grunfeld C, Delaney JA, Wanke C, Currier JS, Scherzer R, Biggs ML, Tien P, Shlipak M, Sidney S, Polak JF, O’Leary D, Bacchetti P, Kronmal R. Preclinical atherosclerosis due to HIV infection: carotid intima-medial thickness measurements from the FRAM study. AIDS. 2009;23:1841–9.

Ceccarelli G, d’Ettorre G, Vullo V. The challenge of cardiovascular diseases in HIV-positive patients: it’s time for redrawing the maps of cardiovascular risk? Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67(1):1–3.

Foldyna B, Fourman LT, Lu MT, Mueller ME, Szilveszter B, Neilan TG, Ho JE, Burdo TH, Lau ES, Stone LA, Toribio M, Srinivasa S, Looby SE, Lo J, Fitch KV, Zanni MV. Sex Differences in Subclinical Coronary Atherosclerotic Plaque Among Individuals with HIV on Antiretroviral Therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;78(4):421–8.

Tarr PE, Ledergerber B, Calmy A, Doco-Lecompte T, Marzel A, Weber R, Kaufmann PA, Nkoulou R, Buechel RR, Kovari H. Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Subclinical coronary artery disease in Swiss HIV-positive and HIV-negative persons. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(23):2147–54.

Luetkens JA, Doerner J, Schwarze-Zander C, Wasmuth JC, Boesecke C, Sprinkart AM, Schmeel FC, Homsi R, Gieseke J, Schild HH, Naehle RJK. C. P. Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Reveals Signs of Subclinical Myocardial In ammation in Asymptomatic HIV-Infected Patients. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:e004091.

Friedrich MG, Strohm O, Schulz-Menger J, Marciniak H, Luft FC, Dietz R. Contrast media-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging visualizes myocardial changes in the course of viral myocarditis. Circulation. 1998;97:1802–9.

Weismann F, Petersen SE, Leeson PM, Francis JM, Robson MD, Wang Q, Choudhury R, Channon KM, Neubauer S. Global impairment of brachial, carotid, and aortic vascular function in young smokers: direct quantification by high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:2056–64. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2004.08.033.

Chai Q, Jovasevic V, Malikov V, Sabo Y, Morham S, Walsh D, Naghavi MH. HIV-1 counteracts an innate restriction by amyloid precursor protein resulting in neurodegeneration. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):1522.

Bacmeister L, Schwarzl M, Warnke S, Stoffers B, Blankenberg S, Westermann D, Lindner D. Inflammation and fibrosis in murine models of heart failure. Basic Res Cardiol. 2019;114(3):19.

Freiberg M. “Sudden cardiac death among HIV-infected and -uninfected veterans,” paper presented at: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Seattle, WA, 4–7 March 2019.

Tseng ZH “HIV post SCD Study: 80% higher rate of autopsy-defined sudden arrhythmic death in HIV” paper presented at: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Seattle, WA, 4–7 March 2019.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C. Borrazzo participated in writing the paper, analyzed the data and performed statistical analysis; G. d’Ettorre and G. Ceccarelli participated in writing the paper, were responsible for study concept and design, and for the supervision and critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content; M. Pacilio and L. Santinelli analyzed the data; E. N. Cavallari, O. Spagnolello, V. Silvestri, and P. Vassalini were responsible for clinical evaluation of the HIV-1 positive patients and performed critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content; C. Scagnolari performed critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content; M. Francone was responsible for the clinical evaluation of the HIV-1 positive patients and performed critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content; C.M Mastroianni and I. Carbone were responsible for study concept and design, and for the supervision and critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the institutional review board (Ethics Committee of Umberto I General Hospital, Rome), and all participants signed written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All the authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Borrazzo, C., d’Ettorre, G., Ceccarelli, G. et al. Unexpected increase of myocardial extracellular volume fraction in low cardiovascular risk HIV patients. transl med commun 5, 24 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41231-020-00077-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41231-020-00077-8